Tang poetry

Tang poetry (traditional Chinese: 唐詩; simplified Chinese: 唐诗; pinyin: Táng shī) refers to poetry written in or around the time of or in the characteristic style of China's Tang dynasty, (June 18, 618 – June 4, 907, including the 690–705 reign of Wu Zetian) and/or follows a certain style, often considered as the Golden Age of Chinese poetry. The Quantangshi includes over 48,900 poems written by over 2,200 authors. During the Tang dynasty, poetry continued to be an important part of social life at all levels of society. Scholars were required to master poetry for the civil service exams, but the art was theoretically available to everyone.[1] This led to a large record of poetry and poets, a partial record of which survives today. Two of the most famous poets of the period were Li Bai and Du Fu. Tang poetry has had an ongoing influence on world literature and modern and quasi-modern poetry.

Contents

1 Periodization

2 Forms

3 Sources

4 The pre-Tang poetic tradition

5 History

5.1 Early Tang

5.2 High Tang

5.3 Middle Tang

5.4 Late Tang

5.5 Continuation in Southern Tang

5.6 After the fall of the Tang dynasty

6 Anthologies

6.1 The 300 Tang Poems

6.1.1 Exemplary verse

7 Translation into western languages

8 Characteristics

9 Relationship to Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism

10 Gender studies

11 See also

12 References

13 Cited works

14 Further reading

15 External links

Periodization

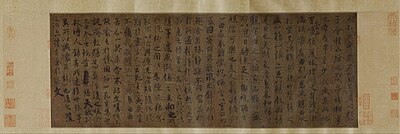

A Tang dynasty era copy of the preface to the Lantingji Xu poems composed at the Orchid Pavilion Gathering, originally attributed to Wang Xizhi (303–361 AD) of the Jin dynasty

The periodization scheme employed in this article is the one detailed by the Ming dynasty scholar Gao Bing (1350–1423) in the preface to his work Tangshi Pinhui, which has enjoyed broad acceptance since his time.[2] This system, which unambiguously treats poetry composed during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (the "High Tang" period) as being superior in quality to what came before and after, is subjective and evaluative, and often does not reflect the realities of literary history.[3]

Forms

The representative form of poetry composed during the Tang dynasty is the shi.[4] This contrasts to poetry composed in the earlier Han dynasty and later Song and Yuan dynasties, which are characterized by fu, ci and qu forms, respectively.[4] However, the fu continued to be composed during the Tang dynasty, which also saw the beginnings of the rise of the ci form.[4]

Within the shi form, there was a preference for pentasyllabic lines, which had been the dominant metre since the second century C.E., but heptasyllabic lines began to grow in popularity from the eighth century.[5] The poems generally consisted of multiple rhyming couplets, with no definite limit on the number of lines but a definite preference for multiples of four lines.[5]

Sources

The Quantangshi ("Complete Tang Poems") anthology compiled in the early eighteenth century includes over 48,900 poems written by over 2,200 authors.[6] The Quantangwen (全唐文, "Complete Tang Prose"), despite its name, contains more than 1,500 fu and is another widely consulted source for Tang poetry.[6] Despite their names, these sources are not comprehensive, and the manuscripts discovered at Dunhuang in the twentieth century included many shi and some fu, as well as variant readings of poems that were also included in the later anthologies.[6] There are also collections of individual poets' work, which generally can be dated earlier than the Qing anthologies, although few earlier than the eleventh century.[7] Only about a hundred Tang poets have such collected editions extant.[7]

Another important source is anthologies of poetry compiled during the Tang dynasty, although only thirteen such anthologies survive in full or in part.[8]

Many records of poetry, as well as other writings, were lost when the Tang capital of Changan was damaged by war in the eighth and ninth centuries, so that while more than 50,000 Tang poems survive (more than any earlier period in Chinese history), this still likely represents only a small portion of the poetry that was actually produced during the period.[7] Many seventh-century poets are reported by the 721 imperial library catalog as having left behind massive volumes of poetry, of which only a tiny portion survives,[7] and there are notable gaps in the poetic œuvres of even Li Bo and Du Fu, the two most celebrated Tang poets.[7]

The pre-Tang poetic tradition

The poetic tradition inherited by the Tang poets was immense and diverse. By the time of the Tang dynasty, there was already a continuous Chinese body of poetry dating back for over a thousand years. Such works as the Chu Ci and Shijing were major influences on Tang poetry, as were the developments of Han poetry and Jian'an poetry. All of these influenced the Six Dynasties poetry, which in turn helped to inspire the Tang poets. In terms of influences upon the poetry of the early Tang, Burton Watson characterizes the poetry of the Sui and early Tang as "a mere continuation of Six Dynasties genres and styles."[9]

History

A poem by Li Bai (701–762 AD), the only surviving example of Li Bai's calligraphy, housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing.

The Tang dynasty was a time of major social and probably linguistic upheavals. Thus, the genre may be divided into several major more-or-less chronological divisions, based on developmental stages or stylistic groupings (sometimes even on personal friendships between poets). It should be remembered that poets may be somewhat arbitrarily assigned to these based on their presumed biographical dates (not always known); furthermore that the lifetimes of poets toward the beginning or end of this period may overlap with the preceding Sui dynasty or the succeeding Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The chronology of Tang poetry may be divided into four parts: Early Tang, High Tang, Middle Tang, and Late Tang.

Early Tang

In Early Tang (初唐), poets began to develop the foundation what is now considered to be the Tang style of poetry inherited a rich and deep literary and poetic tradition, or several traditions. Early Tang poetry is subdivided into early, middle and late phases.

- Some of the initial poets who began to develop what is considered to be the Tang dynasty style of poetry were heavily influenced by the Court Style of the Southern Dynasties (南朝宫), referring to the Southern Dynasties of the Southern and Northern Dynasties time period (420–589 CE) that preceded the short-lived Sui dynasty (581–618 CE). The Southern Dynasty Court (or Palace) poems tended towards an ornate and flowery style and particular vocabulary, partly passed on through continuity of certain governmental individuals who were also poets, during the transition from Sui to Tang. This group includes the emperor Li Shimin, the calligrapher Yu Shinan, Chu Liang (禇亮), Li Baiyao, the governmental official Shangguan Yi, and his granddaughter, the governmental official and later imperial consort Shangguan Wan'er. Indeed, there were many others, as this was a culture that placed a great emphasis on literature and poetry, at least for persons in official capacity and their social intimates.

- Representative of the middle phase of early Tang were the so-called "Four Literary Friends:" poets Li Jiao, Su Weidao, Cui Rong, and Du Shenyan. This represents a transitional phase.

- In the late phase the poetic style becomes more typical of what is considered as Tang poetry. A major influence was Wang Ji (585–644) upon the Four Paragons of the Early Tang: Wang Bo, Yang Jiong, Lu Zhaolin, and Luo Binwang. They each preferred to dispense with literary pretensions in favor of authenticity.

Chen Zi'ang (661–702) is credited with being the great poet who finally brought an end to the Beginning Tang period, casting away the ornate Court style in favor of a hard-hitting, authentic poetry which included political and social commentary (at great risk to himself), and thus leading the way to the greatness that was to come.

High Tang

In High Tang (盛唐), sometimes known as Flourishing Tang or Golden Tang, first appear the poets which would come to mind as Tang poets, at least in the United States and Europe. High Tang poetry had numerous schools of thought:

- The beginning part of this era, or style-period, include Zhang Jiuling (678–740), Wang Han, and Wang Wan. There were also the so-called Four Gentlemen of Wuzhong (吳中四士): He Zhizhang (659–744), Bao Rong, Zhang Xu (658–747, also famous as a calligrapher), and Zhang Ruoxu.

- The "Fields and Gardens Poets Group" (田园诗派) include Meng Haoran (689 or 691–740), the famous poet and painter Wang Wei (701–761), Chu Guangxi (707–760), Chang Jian, Zu Yong (祖咏), Pei Di, Qiwu Qian (綦毋潜), Qiu Wei (丘为), and others.

- The "Borders and Frontier Fortress Poets Group" (Chinese: 邊塞詩派; pinyin: biānsài shī pài) includes Gao Shi (706–765), Cen Shen (715–770), Wang Changling (698–756), Wang Zhihuan, (688–742) Cui Hao (poet) (about 704–754) and Li Qi (690–751).

Li Bai (701–762) and Du Fu (712–770) were the two best-known Tang poets.[7] Li Bai and Du Fu both lived to see the Tang Empire shaken by the catastrophic events of the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763). This had a tremendous impact on their poetry, and indeed signified the end of an era.

Middle Tang

The poets of the Middle Tang (中唐) period also include many of the best known names, and they wrote some very famous poems. This was a time of rebuilding and recovery, but also high taxes, official corruption, and lesser greatness. Li Bo's bold seizing of the old forms and turning them to new and contemporary purposes and Du Fu's development of the formal style of poetry, though hard to equal, and perhaps impossible to surpass, nevertheless provided a firm edifice on which the Middle Tang poets could build.

- In the early phase of the Middle Tang period Du Fu's yuefu poetry was extended by poets such as Dai Shulun (戴叔伦, 732–789) who used the opportunity to admonish governmental officials as to their duties toward the suffering common folk.

- Others concentrated on developing the Landscape Style Poem (山水诗), such as Liu Changqing (刘长卿, 709–780) and Wei Yingwu (韦应物, 737–792).

- The Frontier Fortress Style had its continued advocates, representative of whom are Li Yi (李益) and Lu Lun (卢纶, 739–799).

- The traditional association between poetry and scholarship was shown by the existence of a group of ten poets (大历十才子), who tended to ignore the woes of the people, preferring to sing and chant their poems in praise of peace, beautiful landscapes and the commendability of seclusion. They are: Qian Qi (錢起, 710–782), Lu Lun is also a part of this group, Ji Zhongfu (吉中孚), Han Yi (韩翊), Sikong Shu (司空曙, 720–790), Miao Fa—or Miao Bo – (苗發/苗发), Cui Tong (崔峒), Geng Hui (耿諱/耿讳), Xia Hou Shen (夏侯审), and the poet Li Duan (李端, 743–782).

- One of the greatest Tang poets was Bai Juyi (白居易, 772–846), considered the leader of the somewhat angry, bitter, speaking-truth-to-power New Yuefu Movement (新樂府運動). Among the other poets considered to be part of this movement are Yuan Zhen (元稹, 779–831), Zhang Ji (张籍, 767–830), and Wang Jian (王建).

- Several Tang poets stand out as being to individualistic to really be considered a group, yet sharing a common interest in experimental exploration of the relationship of poetry to words, and pushing the limits thereof; including: Han Yu (韩愈, 768–824), Meng Jiao (孟郊, 751–814), Jia Dao (賈島/贾岛, 779–843), and Lu Tong (盧仝/卢仝, 795–835).

- Two notable poets were Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡, 772–842) and Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元, 773–819).

- Another notable poet, the short-lived Li He (李贺, 790–816), has been called "the Chinese Mallarmé".[10]

Late Tang

In the Late Tang (晚唐), similarly to how eventually the earlier duo of Li Bo and Du Fu came to be known by the combined name of Li-Du (李杜), so in the twilight of the Late Tang there was the duo of the Little Li-Du (小李杜), referring to Du Mu (803–852) and Li Shangyin (813–858). These dual pairs have been considered to typify two divergent poetic streams which existed during each of these two times, the flourishing Tang and the late Tang:

- The Late Tang poetry of Du Mu's type tended toward a clear, robust style, often looking back upon the past with sadness, perhaps reflecting the times. The Tang dynasty was falling apart, it was still in existence, but obviously in a state of decline.

- The poetry of Li Shangyin's type tended towards the sensuously abstract, dense, allusive, and difficult. Other poets of this style were Wen Tingyun (温庭筠, 812–870) and Duan Cheng Shi (段成式, about 803–863). These poets have been attracting gaining interest in modern times.

- There were also other poets belonging to one or the other of two major schools of the Late Tang. in one school were Luo Yin (羅隱/罗隐, 833–909), Nie—or Zhe or She or Ye—Yizhong (聶夷中/聂夷中, 887-884), Du Xunhe (杜荀鹤), Pi Rixiu (皮日休, approximately 834/840—883), Lu Guimeng (陸龜蒙/陆龟蒙 ?-881), and others. In the other group, were Wei Zhuang (韦庄, 836–910), Sikong Tu (司空圖, 837–908), Zheng Gu (鄭谷, 849–911), Han Wo (844-?), and others. During the final twilight of Tang, both schools were prone to a melancholic angst; they varied by whether they tended towards metaphor and allusiveness or a more clear and direct expression.[11][better source needed]

Yu Xuanji was a famous female poet of Late Tang.

Continuation in Southern Tang

After the official fall of the Tang dynasty in 907, some members of its ruling house of Li managed to find refuge in the south of China, where their descendants founded the Southern Tang dynasty in the year 937. This dynasty continued many of the traditions of the former great Tang dynasty, including poetry, until its official fall in 975, when its ruler, Li Yu, was taken into captivity. Importantly for the history of poetry, Li survived another three years as a prisoner of the Song dynasty, and during this time composed some of his best known works.[citation needed] Thus, including this "afterglow of the T'ang dynasty", the final date for the Tang Poetry era can be considered to be at the death of Li Yu, in 978.[12]

After the fall of the Tang dynasty

Surviving the turbulent decades of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era, Tang poetry was perhaps the major influence on the poetry of the Song dynasty, for example seeing such major poets as Su Shi creating new works based upon matching lines of Du Fu's.[13] This matching style is known from the Late Tang. Pi Rixiu and Lu Guimeng, sometimes known as Pi-Lu, were well known for it: one would write a poem with a certain style and rhyme scheme, then the other would reply with a different poem, but matching the style and with the same rhymes. This allows for subtleties which can only be grasped by matching the poems together.

Succeeding eras have seen the popularity of various Tang poets wax and wane. The Qing dynasty saw the publication of the massive compilation of the collected Tang poems, the Quantangshi, as well as the less-scholarly (for example, no textual variants are given), but more popular, Three Hundred Tang Poems. Furthermore, in the Qing dynasty era the imperial civil service examinations the requirement to compose Tang style poetry was restored.[14] In China, some of the poets, such as Li Bo and Du Fu have never fallen into obscurity; others, such as Li Shangyin, have had modern revivals.

Anthologies

Many collections of Tang poetry have been made, both during the Tang dynasty and subsequently. In the first century of the Tang period several early collections of contemporary poetry were made, some of which survive and some which do not: these early anthologies reflect the imperial court context of the early Tang poetry.[15] Later anthologies of Tang poetry compiled during the Qing dynasty include both the imperially commissioned Quan Tang shi and the scholar Sun Zhu's own privately compiled Three Hundred Tang Poems. Part of an anthology by Cui Rong, the Zhuying ji also known as the Collection of Precious Glories has been found among the Dunhuang manuscripts, consisting of about one-fifth of the original, with fifty-five poems by thirteen men, first published in the reign of Wu Zetian (655–683). The book contains poems by Cui Rong (653–706), Li Jiao (644–713), Zhang Yue (677–731), and others.[16]

The 300 Tang Poems

The most popular Tang Poems collection might be the so-called 300 Tang Poems compiled by Qing dynasty scholar Sun Zhu.

It is so popular that many poems in it have been adopted by Chinese language text books of China's primary schools and secondary schools. Some of the poems in it are normally regarded as must-recite ones.

He said he found the poems in the poetry textbook students that had been using, "Poems by A Thousand Writers" (Qian-jia-shi), were not carefully selected but a mixture of Tang dynasty poems and Song dynasty poems written in different styles. He also regarded that some poetry works in that book were not very well-written in terms of language skill and rhyme.

Therefore, he picked those best and most popular poems from Tang dynasty only and formed this new collection of about 310 poems including poems by the most renowned poets such as Li Bai and Du Fu.

These poems are about various topics including friendship, politics, idyllic life and ladies' life, and so on.

Exemplary verse

《旅夜書懷》

杜甫

細草微風岸,危檣獨夜舟。

星垂平野闊,月湧大江流。

名豈文章著,官應老病休。

飄飄何所似?天地一沙鷗。

My Reflection by Night

by Du Fu

Some scattered grass. A shore breeze blowing light.

A giddy mast. A lonely boat at night.

The wide-flung stars o’erhang all vasty space.

The moonbeams with the Yangtze’s current race.

How by my pen can I to fame attain?

Worn out, from office better to refrain.

Drifting o’er life — and what in sooth am I?

A sea-gull floating twixt the Earth and Sky.

Translated by W.J.B. Fletcher (1919)

Translation into western languages

Major translators of Tang poetry into English include Herbert Giles, L. Cranmer-Byng, Archie Barnes, Amy Lowell, Arthur Waley, Witter Bynner, A. C. Graham, Shigeyoshi Obata, Burton Watson, Gary Snyder, David Hinton, Wai-lim Yip, Red Pine (Bill Porter), and Xian Mao. Ezra Pound drew on notes given to him by the widow of Ernest Fenollosa in 1913 to create English poems indirectly through the Japanese, including some Li Bai poems, which were published in his book Cathay.

Characteristics

Tang poetry has certain characteristics. Contextually, the fact that the poems were generally intended to be recited in more-or-less contemporary spoken Chinese (now known as Classical Chinese; or, sometimes, as Literary Chinese, in post-Han dynasty cases) and that the poems were written in Chinese characters are certainly important. Also important are the use of certain typical poetic forms, various common themes, and the surrounding social and natural milieu.

Relationship to Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism

The Tang dynasty time was one of religious ferment, which was reflected in the poetry. Many of the poets were religiously devout. Also, at that time religion tended to have an intimate relation with poetry.

Gender studies

There has been some interest in Tang poetry in the field of gender studies. Although most of the poets were men, there were several significant women. Also, many of the men wrote from the viewpoint of a woman, or lovingly of other men. Historically and geographically localized in Tang dynasty China, this is an area which has not escaped interest from the perspective of historical gender roles.

See also

- 7th century in poetry

- 8th century in poetry

- 9th century in poetry

- Chinese poetry

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Ci (poetry)

- Four Literary Eminences in Early Tang

- Fu (poetry)

- Hanshan (poet)

- Jueju

- List of Chinese language poets

- List of Three Hundred Tang Poems poets

- Quantangshi

- Shi (poetry)

- Song poetry

- Tang dynasty poets (list)

- Three Hundred Tang Poems

- Wangchuan ji

- Yuefu

References

^ Jing-Schmidt, 256, accessed July 20, 2008

^ Paragraph 3 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ Paragraph 4 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ abc Paragraph 1 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ ab Paragraph 5 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ abc Paragraph 15 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ abcdef Paragraph 16 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ Paragraph 17 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ Watson, 109

^ Paragraph 87 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

^ zh.wikipedia "唐诗" (most of this section is adapted from there, along with dates from the linked articles on individual poets)

^ Wu, 190 and chapter on Li Yu 211–221

^ Murck (2000), passim.

^ Yu, 66

^ Yu, 55–57

^ Yu, 56

Cited works

- Hoyt, Ed; Vanessa Lide Whitcomb, Michael Benson (2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Modern China. Alpha Books. .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 0-02-864386-0. - Jing-Schmidt, Zhuo (2005). Dramatized discourse: the Mandarin Chinese ba-construction. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

ISBN 90-272-1565-0.

Mair, Victor H. (ed.) (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

ISBN 0-231-10984-9. (Amazon Kindle edition.)

Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.- Watson, Burton (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. New York: Columbia University Press.

ISBN 0-231-03464-4 - Wu, John C. H. (1972). The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E.Tuttle.

ISBN 978-0-8048-0197-3 - Yu, Pauline (2002). "Chinese Poetry and Its Institutions", in Hsiang Lectures on Chinese Poetry, Volume 2, Grace S. Fong, editor. (Montreal: Center for East Asian Research, McGill University).

Further reading

- Graves, Robert (1969). ON POETRY: Collected Talks and Essays. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

ISBN 0-374-10536-7 /

ISBN 978-0-374-10536-5.

Mao, Xian (2013). New Translation of Most Popular 60 Classical Chinese Poems. eBook: Kindle Direct Publishing. ISBN 978-14685-5904-0.- Stephen Owen. The Poetry of the Early T'ang. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

ISBN 0-300-02103-8. Revised edition, Quirin Press, 2012.

ISBN 978-1-922169-02-0 - Stephen Owen. The Great Age of Chinese Poetry: The High T'ang. New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 1981.

ISBN 0-300-02367-7. Revised edition, Quirin Press, 2013.

ISBN 978-1-922169-06-8 - Stephen Owen. The Late Tang: Chinese Poetry of the Mid-Ninth Century (827–860). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Harvard East Asian Monographs, 2006.

ISBN 0-674-02137-1.

External links

Three Hundred Tang Poems (online : Chinese + English)