Saint Pantaleon

Saint Pantaleon (Panteleimon) | |

|---|---|

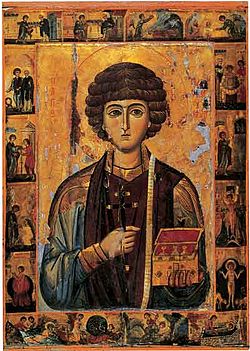

13th century icon of Saint Panteleimon, including scenes from his life, from the Monastery of St. Katherine on Mount Sinai | |

| Great-Martyr and Unmercenary Healer | |

| Born | c. 275 Nicomedia |

| Died | 305[1] Nicomedia |

| Venerated in | Anglicanism Eastern Orthodoxy Oriental Orthodoxy Roman Catholicism |

| Major shrine | Pantaleon Monastery in the Jordan desert, Pantaleon Church built by Emperor Justinian in the 6th century, Constantinople |

| Feast | 27 July[2][3] (Western Christianity, Byzantine Christianity) 19 Epip (Coptic Christianity)[4] 9 August[by whom?] |

| Attributes | A compartmented medicine box, with a long-handled spatula or spoon; a martyr's cross |

| Patronage | Physicians, midwives, livestock, lottery, lottery winners and victories, lottery tickets, invoked against headaches, consumption, locusts, witchcraft, accidents and loneliness, helper for crying children |

Saint Pantaleon (Greek: Παντελεήμων, Russian: Пантелеи́мон, translit. Panteleímon; "all-compassionate"), counted in the West among the late-medieval Fourteen Holy Helpers and in the East as one of the Holy Unmercenary Healers, was a martyr of Nicomedia in Bithynia during the Diocletianic Persecution of 305 AD.

Though there is evidence to suggest that a martyr named Pantaleon existed, some consider the stories of his life and death to be purely legendary.[5]

Contents

1 Life of Pantaleon

2 Early veneration

3 Veneration in the East

4 Veneration in Western Europe

4.1 England

4.2 France

4.3 Germany

4.4 Italy

4.5 Portugal

5 Eponym

6 References

7 External links

Life of Pantaleon

According to the martyrologies, Pantaleon was the son of a rich pagan, Eustorgius of Nicomedia, and had been instructed in Christianity by his Christian mother, Saint Eubula; however, after her death he fell away from the Christian church, while he studied medicine with a renowned physician Euphrosinos; under the patronage of Euphrosinos he became physician to the emperor, Galerius.[5]

St Pantaleon on a tenth-century Byzantine ceramic tile in the State Historical Museum, Moscow

The Church of St. Panteleimon in Gorno Nerezi, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia

Church of St. Panteleimon, built in 1735-1739, is one of the oldest in St. Petersburg

He was won back to Christianity by Saint Hermolaus (characterized as a bishop of the church at Nicomedia in the later literature), who convinced him that Christ was the better physician, signalling the significance of the exemplum of Pantaleon that faith is to be trusted over medical advice.

St. Alphonsus Liguori wrote regarding this incident:

He studied medicine with such success, that the Emperor Maximian appointed him his physician. One day as our saint was discoursing with a holy priest named Hermolaus, the latter, after praising the study of medicine, concluded thus: "But, my friend, of what use are all thy acquirements in this art, since thou art ignorant of the science of salvation?[6]

By miraculously healing a blind man by invoking the name of Jesus over him, Pantaleon converted his father, upon whose death he came into possession of a large fortune. He freed his slaves and, distributing his wealth among the poor, developed a great reputation in Nicomedia. Envious colleagues denounced him to the emperor during the Diocletian persecution. The emperor wished to save him and sought to persuade him to apostasy. Pantaleon, however, openly confessed his faith, and as proof that Christ was the true God, he healed a paralytic. Notwithstanding this, he was condemned to death by the emperor, who regarded the miracle as an exhibition of magic.[7]

According to the legend, Pantaleon's flesh was first burned with torches, whereupon Christ appeared to all in the form of Hermolaus to strengthen and heal Pantaleon. The torches were extinguished. Then a bath of molten lead was prepared; when the apparition of Christ stepped into the cauldron with him, the fire went out and the lead became cold. Pantaleon was now thrown into the sea, loaded with a great stone, which floated. He was thrown to wild beasts, but these fawned upon him and could not be forced away until he had blessed them. He was bound on the wheel, but the ropes snapped, and the wheel broke. An attempt was made to behead him, but the sword bent, and the executioners were converted to Christianity.[7]

Pantaleon implored Heaven to forgive them, for which reason he also received the name of Panteleimon ("mercy for everyone" or "all-compassionate"). It was not until he himself desired it that it was possible to behead him, upon which there issued forth blood and a white liquid like milk.

St. Alphonsus wrote:

At Ravello, a city in the kingdom of Naples, there is a vial of his blood, which becomes blood every year [on his feastday], and may be seen in this state interspersed with the milk, as I, the author of this work, have seen it.[6]

Early veneration

The vitae containing these miraculous features are all late in date and "valueless" according to the Catholic Encyclopedia.[7] Yet the fact of his martyrdom itself seems to be supported by a veneration for which there is testimony in the 5th century, among others in a sermon on the martyrs by Theodoret (died c. 457);[8]Procopius of Caesarea (died c. 565?), writing on the churches and shrines constructed by Justinian I[9] tells that the emperor rebuilt the shrine to Pantaleon at Nicomedia; and there is mention of Pantaleon in the Martyrologium Hieronymianum.[10]

Veneration in the East

Panteleimon, is shown here with a lancet in his right hand. This tile probably formed a frieze on a church wall or altar screen.[11]The Walters Art Museum.

The Eastern tradition concerning Pantaleon follows more or less the medieval Western hagiography, but lacks any mention of a visible apparition of Christ. It states instead that Hermolaus was still alive while Pantaleon's torture was under way, but was martyred himself only shortly before Pantaleon's beheading along with two companions, Hermippas and Thermocrates. The saint is canonically depicted as a beardless young man with a full head of curly hair.

Pantaleon's relics, venerated at Nicomedia, were transferred to Constantinople. Numerous churches, shrines, and monasteries have been named for him; in the West most often as St. Pantaleon and in the East as St. Panteleimon; to him is consecrated the St. Panteleimon Monastery at Mount Athos, St Panteleimon monastery in Myrtou, Cyprus, and the 12th-century Church of St. Panteleimon in Gorno Nerezi, Republic of Macedonia.

Armenians believe that the Gandzasar Monastery in Nagorno Karabakh contains relics of St. Pantaleon, who was venerated in eastern provinces of Armenia.

Veneration in Western Europe

At the Basilica of the Vierzehnheiligen near Staffelstein in Franconia, St. Pantaleon is venerated with his hands nailed to his head, reflecting another legend about his death.

After the Black Death of the mid-14th century in Western Europe, as a patron saint of physicians and midwives, he came to be regarded as one of the fourteen guardian martyrs, the Fourteen Holy Helpers. Relics of the saint are found at Saint Denis at Paris; his head is venerated at Lyon. A Romanesque church was dedicated to him in Cologne in the 9th century at the latest.

England

In the British Library there is a surviving manuscript, written in Saxon Old English, of The Life of St Pantaleon (British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius D XVII), dating from the early eleventh century, possibly written for Abbot Ælfric of Eynsham.[12] The Canons' Vestry off the south transept of Chichester Cathedral was formerly a square-plan chapel dedicated to Saint Pantaleon - it was possibly under construction just before the cathedral's great fire of 1187.[13]

France

In France, he was depicted in a window in Chartres Cathedral.[5] In southern France there are six communes under the protective name of Saint-Pantaléon. Though there are individual churches consecrated to him elsewhere, there are no communes named for him in the north or northwest of France. The six are:

Saint-Pantaléon, in the Lot département, Midi-Pyrénées

Saint-Pantaléon, in the Vaucluse département, Provence - a wine-growing village

Saint-Pantaléon-de-Lapleau, in the Corrèze département, Limousin

Saint-Pantaléon-de-Larche, in the Corrèze département, at the border of Périgord and Quercy

Saint-Pantaléon-les-Vignes, in the Drôme département, Rhône-Alpes – a wine-growing village[14] that is part of the Côtes du Rhône vinyard region- Saint-Pantaléon, in the Saône-et-Loire département, Bourgogne – administratively linked to Autun, bishopric see

Germany

In Cologne a 10th Century Romanesque church, partly built by the daughter of the Byzantine emperor, Theophanu, who married the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II in 972

Saint Pantaleon, in Cologne

Italy

In Italy, Pantaleon gives favourable lottery numbers, victories and winners in dreams.[15] A phial containing some of his blood was long preserved at Ravello.[5] On the feast day of the saint, the blood was said to become fluid and to bubble (compare Saint Januarius). Paolo Veronese's painting of Pantaleon can be found in the church of San Pantalon in Venice; it shows the saint healing a child. Another painting of Pantaleon by Fumiani is also in the same church.[5] He was depicted in an 8th-century fresco in Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome, and in a 10th-century cycle of pictures in the crypt of San Crisogono in Rome.[5] In Calabria, there is a small town named Papanice, after Pantaleon. Each year on his feast day, a statue of the saint is carried through the town to give a blessing for all those who seek it.

San Pantaleone or Pantalone was a popular saint in Venice, and he therefore gave his name to a character in the commedia dell'arte, Pantalone, a silly, wizened old man (Shakespeare's "lean and slippered Pantaloon") who was a caricature of Venetians. This character was portrayed as wearing trousers rather than knee breeches, and so became the origin of the name of a type of trouser called "pantaloons," which was later shortened to "pants".[16]

Portugal

Saint Pantaleon (São Pantalião in Portuguese) is one of the patron saints of the city of Porto in Portugal[17], together with John the Baptist and Our Lady of Vendome. Part of his relics were brought by Armenian refugees to the city after the Turkish occupation of Constantinople in 1453.[18] Later, in 1499, these relics were transferred from the Church of Saint Peter of Miragaia to the Cathedral, where they have been kept to this day.[19]

Eponym

- Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias, the first European known to have sailed around the Cape of Good Hope, took a ship named São Pantaleão on that expedition.

- The Russian battleship Potemkin was renamed Panteleimon after her recovery after the mutiny of 1905

- St. Pantaleon is the eponym of the character Pantalaimon in Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials series of novels

References

^ Antonelli, Antonello. "San Pantaleone" Santi e beati

^ Online, Catholic. "St. Pantaleon - Saints & Angels - Catholic Online"..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ http://98.131.104.126/prolog/July27.htm

^ "The Martyrdom of St. Pantaleemon, the Physician", Coptic Orthodox Church Network

^ abcdef Butler, Alban (2000). Butler's Lives of the Saints. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 217.

^ ab Liguori, Alphonsus (1888). "SS. Hermolaus, Priest; and Pantaleon, Physician". Victories of the Martyrs. London: Benziger Brothers. pp. 308–311.

^ abc Löffler, Klemens (1911). "St. Pantaleon". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 11. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

^ Graecarum affectionum curatio, Sermo VIII, "De martyribus", published in Migne, Patrologia Graeca, LXXXIII 1033

^ De aedificiis Justiniani (I, ix; V, ix)

^ Bollandists' Acta Sanctorum for November, II, 1, 97

^ "Saint Panteleimon". The Walters Art Museum.

^ Joana Proud, 'The Old English 'Life of Saint Pantaleon' and its manuscript context' in Bulletin of the John Rylands Library (1997, vol. 79, no. 3, pp.119-132

^ "Chichester cathedral: Historical survey - British History Online".

^ http://www.cave-st-pantaleon.com

^ Jockle, Clemens (1995). Encyclopedia of Saints. London: Alpine Fine Arts Collection. p. 349.

^ Harper, Douglas. "Pantaloon". Etymology Online. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

^ Patterson, A.D. (1846). The Anglo-American, a journal of literature, news, politics, the drama, fine arts, etc. New York: E.L. Garvin and Co. p. 386.

^ Rioboom, Sarah. "Pantalião". Portualities. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

^ Ferrão Afonso, José. "Pantalião II".On 12 December 1499, Bishop Diogo de Sousa, in solemn procession, transferred the relics of St. Pantaleon, deposited in the parish church of S. Pedro de Miragaia, to the Cathedral

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Pantaleon. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: St. Pantaleon |

- Life of St Panteleimon with a portrait in the traditional icon style

Paul Gerhard Aring (1993). "Pantaleon". In Bautz, Traugott. Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 6. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 1485–1486. ISBN 3-88309-044-1.

Paul Guérin, Les Petits Bollandistes: Vies des Saints, (Bloud et Barral: Paris, 1882), Vol. 9 Hagiography for children (in English)- Article in OrthodoxWiki

- St. Panteleimon

- Gandzasar Monastery, Nagorno Karabakh