Military saint

Four Military Saints by Michael Damaskinos (16th century, Benaki Museum), showing St George and St Theodore Teron on the left, and St Demetrios and St Theodore Stratelates on the right, all on horseback, with angels holding wreaths over their heads, beneath Christ Pantokrator.

Triptych of the Bogomater flanked by Saints George and Demetrius as horsemen (dated 1754)

The military saints or warrior saints (also called soldier saints) of the Early Christian Church are

Christian saints who were soldiers in the Roman Army during the persecution of Christians, especially the Diocletian persecution of AD 303–313.

Most were soldiers of the Empire who had become Christian and, after refusing to participate in rituals of loyalty to the Emperor (see Imperial cult), were subjected to corporal punishment including torture and martyrdom.

Veneration of these saints, most notably of Saint George, was reinforced in Western tradition during the time of the Crusades.

The title of "champion of Christ" (athleta Christi) was originally used for these saints, but in the late medieval period also conferred on contemporary rulers by the Pope.[citation needed]

Contents

1 Iconography

2 Hagiography

3 List of military saints

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

Iconography

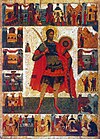

The military saints are characteristically depicted as soldiers in traditional Byzantine iconography from about the 10th century (Macedonian dynasty) and especially also in Slavic Christianity.[1]

While early icons show the saints in "classicizing" attire, icons from the 11th and especially the 12th centuries, painted in the new style of τύπων μιμήματα (imitating nature), are an important source for our knowledge of medieval Byzantine military equipment.[2]

The angelic prototype of the Christian soldier-saint is the Archangel Michael, whose earliest known cultus began in the 5th century with a shrine at Monte Gargano.

The iconography of soldier-saints Theodore and George

as cavalrymen develops in the early medieval period.

The earliest image of St Theodore as a horseman (named in Latin) is from Vinica, North Macedonia and, if genuine, dates to the 6th or 7th century. Here, Theodore is not slaying a dragon, but holding a draco standard.

Three equestrian saints, Demetrius, Theodore and George, are depicted in the "Zoodochos Pigi" chapel in central Macedonia in Greece, in the prefecture of Kilkis, near the modern village of Kolchida, dated to the 9th or 10th century.[3]

The "dragon-slaying" motif develops in the 10th century, especially iconography seen in the Cappadocian cave churches of Göreme, where frescoes of the 10th century show military saints on horseback confronting serpents with one, two or three heads.[4]

In later medieval Byzantine iconography, the pair of horsemen is no longer identified as Theodore and George, but as George and Demetrius.

Hagiography

In Late Antiquity other Christian writers of hagiography, like Sulpicius Severus in his account of the heroic, military life of Martin of Tours, created a literary model that reflected the new spiritual, political, and social ideals of a post-Roman society.

In a study of Anglo-Saxon soldier saints (Damon 2003), J.E. Damon has demonstrated the persistence of Sulpicius's literary model in the transformation of the pious, peaceful saints and willing martyrs of late antique hagiography to the Christian heroes of the early Middle Ages, who appealed to the newly converted societies led by professional warriors and who exemplified accommodation with and eventually active participation in holy wars that were considered just.[5]

List of military saints

| Image | Name | Martyrdom | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acacius | c. 303 | Byzantium | |

| Andrew the General | c. 300 | Cilicia | |

| Demetrius of Thessaloniki | 304 | Sirmium |

| Emeterius and Chelidonius | c. 300 | Calagurris in Hispania Tarraconensis | |

| Eustace | ||

| Expeditus | c. 303 | Melitene, Cappadocia | |

| Florian | c. 303 | Lauriacum in Noricum | |

| George | c. 303 | Nicomedia in Bithynia |

| Gereon | c. 304 | |

| Maurice and the Theban Legion | 287 | Agaunum in Alpes Poeninae et Graiae |

| Martin of Tours | —[6] | |

| Maximilian | 295 | Tebessa in Africa Proconsularis | |

| Marcellus of Tangier | 298 | Tingis in Mauretania Tingitana | |

| Menas | c. 309 | Cotyaeum in Phrygia | |

| Mercurius | 250 | Caesarea in Cappadocia | |

| Sergius and Bacchus | c. 305 | Resafa and Barbalissus in Syria Euphratensis | |

| Theodore of Amasea | 306 | Amasea in Helenopontus | |

| Typasius the Veteran | 304 | Tigava in Mauretania Caesariensis | |

Vardan | 387 | Armenia | |

| Varus | c. 307 | Egypt | |

| Victor the Moor | c. 303 | Milan in Italy | |

| Nicetas the Goth | 372 | Dacia |

| Forty Martyrs of Sebaste | 320 | Sebaste |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to military saints. |

- Christians in the military

- Patron saints of the military

- Saint George: Devotions, traditions and prayers

- Military ordinariate

- Military order (monastic society)

References

^ "The 'warrior saints' or 'military saints' can be distinguished from the huge host of martyrs by the pictorial convention of cladding them in military attire." (Grotowski 2010:2)

^ (Grotowski 2010:400)

^ Melina Paissidou, "Warrior Saints as Protectors of the Byzantine Army in the Palaiologan Period: the Case of the Rock-cut Hermitage in Kolchida (Kilkis Prefecture)", in: Ivanka Gergova Emmanuel Moutafov (eds.), ГЕРОИ • КУЛТОВЕ • СВЕТЦИ / Heroes Cults Saints Sofija (2015), 181-198.

^ Paul Stephenson, The Serpent Column: A Cultural Biography, Oxford University Press (2016), 179–182.

^ Damon, John Edward. Soldier Saints and Holy Warriors: Warfare and Sanctity in the Literature of Early England. (Burlington (VT): Ashgate Publishing Company), 2003, .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 0-7546-0473-X

^ Martin is not a martyr, and not a classical military saint.

He came to be venerated as "military saint" in 19th to 20th-century French nationalism due to his successful promotion as such during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1.

Brennan, Brian, The Revival of the Cult of Martin of Tours in the Third Republic (1997).

- Monica White, Military Saints in Byzantium and Rus, 900–1200 (2013).

- Christopher Walter, The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition (2003).

- Piotr Grotowski, Arms and Armour of the Warrior Saints: Tradition and Innovation in Byzantine Iconography (843–1261), Volume 87 of The Medieval Mediterranean (2010).

External links

David Woods, "The Military Martyrs" (ucc.ie)

The Warrior Saints (iconreader.wordpress.com) (2012)