Harmonic

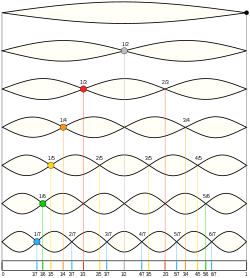

The nodes of a vibrating string are harmonics.

Two different notations of natural harmonics on the cello. First as sounded (more common), then as fingered (easier to sightread).

A harmonic is any member of the harmonic series. The term is employed in various disciplines, including music, physics, acoustics, electronic power transmission, radio technology, and other fields. It is typically applied to repeating signals, such as sinusoidal waves. A harmonic of such a wave is a wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the frequency of the original wave, known as the fundamental frequency. The original wave is also called the 1st harmonic, the following harmonics are known as higher harmonics. As all harmonics are periodic at the fundamental frequency, the sum of harmonics is also periodic at that frequency. For example, if the fundamental frequency is 50 Hz, a common AC power supply frequency, the frequencies of the first three higher harmonics are 100 Hz (2nd harmonic), 150 Hz (3rd harmonic), 200 Hz (4th harmonic) and any addition of waves with these frequencies is periodic at 50 Hz.

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

An nth characteristic mode, for n > 1, will have nodes that are not vibrating. For example, the 3rd characteristic mode will have nodes at 13displaystyle tfrac 13

L and 23displaystyle tfrac 23

L, where L is the length of the string. In fact, each nth characteristic mode, for n not a multiple of 3, will not have nodes at these points. These other characteristic modes will be vibrating at the positions 13displaystyle tfrac 13

L and 23displaystyle tfrac 23

L. If the player gently touches one of these positions, then these other characteristic modes will be suppressed. The tonal harmonics from these other characteristic modes will then also be suppressed. Consequently, the tonal harmonics from the nth characteristic modes, where n is a multiple of 3, will be made relatively more prominent.[1]

In music, harmonics are used on string instruments and wind instruments as a way of producing sound on the instrument, particularly to play higher notes and, with strings, obtain notes that have a unique sound quality or "tone colour". On strings, harmonics that are bowed have a "glassy", pure tone. On stringed instruments, harmonics are played by touching (but not fully pressing down the string) at an exact point on the string while sounding the string (plucking, bowing, etc.); this allows the harmonic to sound, a pitch which is always higher than the fundamental frequency of the string.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 Characteristics

3 Partials, overtones, and harmonics

4 On stringed instruments

4.1 Table

4.2 Artificial harmonics

5 Other information

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Terminology

Harmonics may also be called "overtones", "partials" or "upper partials". The difference between "harmonic" and "overtone" is that the term "harmonic" includes all of the notes in a series, including the fundamental frequency (e.g., the open string of a guitar). The term "overtone" only includes the pitches above the fundamental. In some music contexts, the terms "harmonic", "overtone" and "partial" are used fairly interchangeably.

Characteristics

A whizzing, whistling tonal character, distinguishes all the harmonics both natural and artificial from the firmly stopped intervals; therefore their application in connection with the latter must always be carefully considered.[2]

Most acoustic instruments emit complex tones containing many individual partials (component simple tones or sinusoidal waves), but the untrained human ear typically does not perceive those partials as separate phenomena. Rather, a musical note is perceived as one sound, the quality or timbre of that sound being a result of the relative strengths of the individual partials. Many acoustic oscillators, such as the human voice or a bowed violin string, produce complex tones that are more or less periodic, and thus are composed of partials that are near matches to integer multiples of the fundamental frequency and therefore resemble the ideal harmonics and are called "harmonic partials" or simply "harmonics" for convenience (although it's not strictly accurate to call a partial a harmonic, the first being real and the second being ideal).

Oscillators that produce harmonic partials behave somewhat like one-dimensional resonators, and are often long and thin, such as a guitar string or a column of air open at both ends (as with the modern orchestral transverse flute). Wind instruments whose air column is open at only one end, such as trumpets and clarinets, also produce partials resembling harmonics. However they only produce partials matching the odd harmonics, at least in theory. The reality of acoustic instruments is such that none of them behaves as perfectly as the somewhat simplified theoretical models would predict.

Partials whose frequencies are not integer multiples of the fundamental are referred to as inharmonic partials. Some acoustic instruments emit a mix of harmonic and inharmonic partials but still produce an effect on the ear of having a definite fundamental pitch, such as pianos, strings plucked pizzicato, vibraphones, marimbas, and certain pure-sounding bells or chimes. Antique singing bowls are known for producing multiple harmonic partials or multiphonics.

[3][4] Other oscillators, such as cymbals, drum heads, and other percussion instruments, naturally produce an abundance of inharmonic partials and do not imply any particular pitch, and therefore cannot be used melodically or harmonically in the same way other instruments can.

Partials, overtones, and harmonics

An overtone is any partial higher than the lowest partial in a compound tone. The relative strengths and frequency relationships of the component partials determine the timbre of an instrument. The similarity between the terms overtone and partial sometimes leads to their being loosely used interchangeably in a musical context, but they are counted differently, leading to some possible confusion. In the special case of instrumental timbres whose component partials closely match a harmonic series (such as with most strings and winds) rather than being inharmonic partials (such as with most pitched percussion instruments), it is also convenient to call the component partials "harmonics" but not strictly correct (because harmonics are numbered the same even when missing, while partials and overtones are only counted when present). This chart demonstrates how the three types of names (partial, overtone, and harmonic) are counted (assuming that the harmonics are present):

| Frequency | Order | Name 1 | Name 2 | Name 3 | Wave Representation | Molecular Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × f = 0440 Hz | n = 1 | 1st partial | fundamental tone | 1st harmonic |  |  |

| 2 × f = 0880 Hz | n = 2 | 2nd partial | 1st overtone | 2nd harmonic |  |  |

| 3 × f = 1320 Hz | n = 3 | 3rd partial | 2nd overtone | 3rd harmonic |  |  |

| 4 × f = 1760 Hz | n = 4 | 4th partial | 3rd overtone | 4th harmonic |  |  |

In many musical instruments, it is possible to play the upper harmonics without the fundamental note being present. In a simple case (e.g., recorder) this has the effect of making the note go up in pitch by an octave, but in more complex cases many other pitch variations are obtained. In some cases it also changes the timbre of the note. This is part of the normal method of obtaining higher notes in wind instruments, where it is called overblowing. The extended technique of playing multiphonics also produces harmonics. On string instruments it is possible to produce very pure sounding notes, called harmonics or flageolets by string players, which have an eerie quality, as well as being high in pitch. Harmonics may be used to check at a unison the tuning of strings that are not tuned to the unison. For example, lightly fingering the node found halfway down the highest string of a cello produces the same pitch as lightly fingering the node 1⁄3 of the way down the second highest string. For the human voice see Overtone singing, which uses harmonics.

While it is true that electronically produced periodic tones (e.g. square waves or other non-sinusoidal waves) have "harmonics" that are whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency, practical instruments do not all have this characteristic. For example, higher "harmonics"' of piano notes are not true harmonics but are "overtones" and can be very sharp, i.e. a higher frequency than given by a pure harmonic series. This is especially true of instruments other than stringed or brass/woodwind ones, e.g., xylophone, drums, bells etc., where not all the overtones have a simple whole number ratio with the fundamental frequency. The fundamental frequency is the reciprocal of the period of the periodic phenomenon.[5]

On stringed instruments

Playing a harmonic on a string

Harmonics may be singly produced [on stringed instruments] (1) by varying the point of contact with the bow, or (2) by slightly pressing the string at the nodes, or divisions of its aliquot parts (12displaystyle tfrac 12

, 13displaystyle tfrac 13

, 14displaystyle tfrac 14

, etc.). (1) In the first case, advancing the bow from the usual place where the fundamental note is produced, towards the bridge, the whole scale of harmonics may be produced in succession, on an old and highly resonant instrument. The employment of this means produces the effect called 'sul ponticello.' (2) The production of harmonics by the slight pressure of the finger on the open string is more useful. When produced by pressing slightly on the various nodes of the open strings they are called 'Natural harmonics.' ... Violinists are well aware that the longer the string in proportion to its thickness, the greater the number of upper harmonics it can be made to yield.

— Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1879)[6]

The following table displays the stop points on a stringed instrument, such as the guitar (guitar harmonics), at which gentle touching of a string will force it into a harmonic mode when vibrated. String harmonics (flageolet tones) are described as having a "flutelike, silvery quality" that can be highly effective as a special color or tone color (timbre) when used and heard in orchestration.[7] It is unusual to encounter natural harmonics higher than the fifth partial on any stringed instrument except the double bass, on account of its much longer strings.[8] Harmonics are widely used in plucked string instruments, such as acoustic guitar, electric guitar and electric bass. On an electric guitar played loudly through a guitar amplifier with distortion, harmonics are more sustained and can be used in guitar solos. In the heavy metal music lead guitar style known as shred guitar, harmonics, both natural and artificial, are widely used.

| Harmonic | Stop note | Sounded note relative to open string | Cents above open string | Cents reduced to one octave | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | octave | octave (P8) | 1,200.0 | 0.0 | |

| 3 | just perfect fifth | P8 + just perfect fifth (P5) | 1,902.0 | 702.0 | |

| 4 | just perfect fourth | 2P8 | 2,400.0 | 0.0 | |

| 5 | just major third | 2P8 + just major third (M3) | 2,786.3 | 386.3 | |

| 6 | just minor third | 2P8 + P5 | 3,102.0 | 702.0 | |

| 7 | septimal minor third | 2P8 + septimal minor seventh (m7) | 3,368.8 | 968.8 | |

| 8 | septimal major second | 3P8 | 3,600.0 | 0.0 | |

| 9 | Pythagorean major second | 3P8 + Pythagorean major second (M2) | 3,803.9 | 203.9 | |

| 10 | just minor whole tone | 3P8 + just M3 | 3,986.3 | 386.3 | |

| 11 | greater undecimal neutral second | 3P8 + lesser undecimal tritone | 4,151.3 | 551.3 | |

| 12 | lesser undecimal neutral second | 3P8 + P5 | 4,302.0 | 702.0 | |

| 13 | tridecimal 2/3-tone | 3P8 + tridecimal neutral sixth (n6) | 4,440.5 | 840.5 | |

| 14 | 2/3-tone | 3P8 + P5 + septimal minor third (m3) | 4,568.8 | 968.8 | |

| 15 | septimal (or major) diatonic semitone | 3P8 + just major seventh (M7) | 4,688.3 | 1,088.3 | |

| 16 | just (or minor) diatonic semitone | 4P8 | 4,800.0 | 0.0 |

Table

Table of harmonics of a stringed instrument with colored dots indicating which positions can be lightly fingered to generate just intervals up to the 7th harmonic

Artificial harmonics

Although harmonics are most often used on open strings (natural harmonics), occasionally a score will call for an artificial harmonic, produced by playing an overtone on an already stopped string. As a performance technique, it is accomplished by using two fingers on the fingerboard, the first to shorten the string to the desired fundamental, with the second touching the node corresponding to the appropriate harmonic. On fretted instruments, such as an electric guitar, the performer can look at the frets to determine where to stop the string and where to touch the node. On unfretted instruments, such as the violin and related instruments, playing artificial harmonics is an advanced technique, as it requires the performer to find two precise locations on the same string.

Other information

Harmonics may be either used or considered as the basis of just intonation systems. Composer Arnold Dreyblatt is able to bring out different harmonics on the single string of his modified double bass by slightly altering his unique bowing technique halfway between hitting and bowing the strings. Composer Lawrence Ball uses harmonics to generate music electronically.

See also

- Aristoxenus

- Electronic tuner

- Formant

- Fourier series

- Guitar harmonic

- Harmonics (electrical power)

- Harmonic oscillator

- Harmonic series (music)

- Harmony

- Pure tone

- Pythagorean tuning

- Scale of harmonics

- Spherical harmonics

- Stretched octave

- Subharmonic

- Xenharmonic music

References

^ Walker, James and Don, Gary (2013). Mathematics and Music, p. 147. CRC. .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 9781439867099.

^ Scholz, Richard (1900). The Technique of the Violin, p. 9. Translated by Saenger, Gustav; ed. New York: Carl Fischer. [ISBN unspecified].

^ Acoustical Society of America – Large grand and small upright pianos Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine by Alexander Galembo and Lola L. Cuddly

^ Hanna Järveläinen et al. 1999. "Audibility of Inharmonicity in String Instrument Sounds, and Implications to Digital Sound Systems"

^ This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

^ Grove, George (1879). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1889), Vol. 2, p. 665. Macmillan. [ISBN unspecified].

^ Kennan, Kent and Grantham, Donald (2002/1952). The Technique of Orchestration, p. 69. Sixth Edition.

ISBN 0-13-040771-2.

^ Kennan & Grantham, ibid, p. 71.

External links

- Harmonics, partials and overtones from fundamental frequency

- Discussion of Sciarrino's violin etudes and notation issues

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Harmonics

- Hear and see harmonics on a Piano