Davidian Revolution

Steel engraving and enhancement of the obverse side of the Great Seal of David I, portraying David in the "European" fashion of the other worldly maintainer of peace and defender of justice.

The Davidian Revolution is a term given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian Reform, foundation of monasteries, Normanization of the Scottish government, and the introduction of feudalism through immigrant Norman and Anglo-Norman knights.

Contents

1 Overview

1.1 European Revolution: the wider context

1.2 European revolution: the Gaelic context

2 Government and feudalism

2.1 Military feudalism

2.2 Anglo-Normanizing government

3 David I and the economy

3.1 Alston mines

3.2 Creation of burghs

3.3 Effect of the burghs

4 Religious reform

4.1 Monastic patronage

4.2 Bishopric of Glasgow

4.3 Church organization

5 Notes

6 References

6.1 Primary sources

6.2 Secondary sources

Overview

King David I is still widely regarded as one of the most significant rulers in Scotland's history. The reason is what Barrow and Lynch both call the "Davidian Revolution".[1] David's "revolution" is held to underpin the development of later medieval Scotland, whereby the changes that he inaugurated grew into most of the central non-native institutions of the later medieval kingdom. Barrow summarizes the many and varied goals of David I, all of which began and ended with his determination "to surround his fortified royal residence and its mercantile and ecclesiastical satellites with a ring of close friends and supporters, bound to him and his heirs by feudal obligation and capable of rendering him military service of the most up-to-date kind and filling administrative offices at the highest level".[2]

European Revolution: the wider context

Since Robert Bartlett's The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (1993), reinforced by Moore's The First European Revolution, c.970–1215 (2000), it has become increasingly apparent that better understanding of David's "revolution" can be achieved by placing it in the context of a wider European "revolution". The central idea is that from the late 10th century onwards the culture and institutions of the old Carolingian heartlands in northern France and western Germany spread to outlying areas, creating a more recognizable "Europe". In this model, the old Carolingian Empire formed a "core" and the outlying areas a "periphery". The Norman conquest of England in the years after 1066 is considered to have made England more like if not part of this "core". In applying this model to Scotland, it would be considered that, as recently as the reign of David's father Máel Coluim III, "peripheral" Scotland had lacked – in relation to the "core" cultural regions of northern France, western Germany and England – respectable Catholic religion, a truly centralized royal government, conventional written documents of any sort, native coins, a single merchant town, as well as the essential castle-building cavalry elite. After David's reign, it had gained all of these.[3]

During the reign of king David I, then, comparatively straightforward evidence of "Europeanization" was produced in Scotland – that adoption of the homogenized political, economic, social and cultural modes of medieval civilization, suitably modified for the distinctive Scottish milieu, which in tandem with similar adoptions elsewhere led to the creation of "Europe" as an identifiable entity for the first time.[4] This is not to say that the Gaelic matrix into which these additions were disseminated was somehow destroyed or swept away; that was not the way in which the paradigm or "blueprint" of medieval Europe functioned – it was only a guide, one that specialized in amelioration, and not (usually) demolition.[5]

European revolution: the Gaelic context

Yet, David's life as a "reformer" also has a context in the Gaelic-speaking world. This is particularly true in understanding David's enthusiasm for the Gregorian Reform. The latter was a revolutionary movement within the western church partly pioneered in the papacy of Pope Gregory VII which sought renewed spiritual rigour, ecclesiastical discipline and doctrinal obedience to the papacy and its sponsored theologians.[6] The Normans who came to England adopted this ideology, and soon began attacking the Scottish and Irish Gaelic world as spiritually backward – a mindset which even underlay the hagiography of David's mother Margaret, written by her confessor Thurgot at the instigation of the English royal court.[7] Yet up until this period, Gaelic monks (often called Céli Dé) from Ireland and Scotland had been pioneering their own kind of ascetic reform both in Great Britain and in continental Europe, where they founded many of their own monastic houses.[8] Since the end of the 11th century various Gaelic princes had themselves been attempting to accommodate Gregorian reform, examples being Muirchertach Ua Briain, Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair, and Edgar and Alexander I of Scotland.[9] Benjamin Hudson stresses the cultural unity of Scotland and Ireland in this period, and uses the example of cooperation between David I, the Scottish reformer, and his Irish counterpart St Malachy, to show at least partly that David's actions can be understood in the Gaelic context as much as the Anglo-Norman one.[10] Indeed, the Gaelic world had never been closed off from its neighbours in England or continental Europe. Gaelic warriors and holymen had been travelling regularly through England and the continent for centuries. David's predecessor Mac Bethad mac Findlaích (King, 1040–57) had employed Norman mercenaries even before the conquest of England,[11] and English exiles after the conquest fled to the courts of both Máel Coluim III, King of Scotland, and Toirdelbach Ua Briain, High King of Ireland.[12]

Government and feudalism

A detail from the Bayeux Tapestry illustrating Norman knights in combat half a century before David's reign.

The widespread infeftment of foreign knights and the processes by which land ownership was converted from a matter of customary tenure into a matter of feudal or otherwise legally-defined relationships revolutionized the way the Kingdom of Scotland was governed, as did the dispersal and installation of royal agents in the new mottes that were proliferating throughout the realm to staff newly created sheriffdoms and judiciaries for the twin purposes of law-enforcement and taxation, bringing Scotland further into the "European" model.[13]

Military feudalism

During this period, Scotland experienced innovations in governmental practices and the importation of foreign, generally French, knights. It is to David's reign that the beginnings of feudalism are generally assigned. Geoffrey Barrow wrote that David's reign witnessed "a revolution in Scots dynastic law" as well as "fundamental innovations in military organization" and "in the composition and dominant characteristics of its ruling class".[14] This is defined as "castle-building, the regular use of professional cavalry, the knight's fee" as well as "homage and fealty". David established large scale feudal lordships in the west of his Cumbrian principality for the leading members of the French military entourage who kept him in power. Additionally, many smaller scale feudal lordships were created. One example would be Freskin. The latter's name occurs in a charter by David's grandson King William to Freskin's son, William, granting Strathbrock in West Lothian and Duffus, Kintrae, and other lands in Moray, "which his father held in the time of King David".[15] The name Freskin is Flemish,[16] and in the words of Geoffrey Barrow "it is virtually certain that Freskin belonged to a large group of Flemish settlers who came to Scotland in the middle decades of the 12th century and were chiefly to be found in West Lothian and the valley of the Clyde".[17] Freskin was responsible for building a castle in the distant territory of Moray, and because Freskin had no kinship ties to the locality, his position was dependent entirely on the king, thus bringing the territory more firmly under royal control. Freskin's land acquisition does not appear to be unique, and may have been part of a royal policy in the aftermath of the defeat of king Óengus of Moray.[18]

Duffus Castle, possibly begun by Freskin, one of David's most successful small scale military immigrants.

Anglo-Normanizing government

Steps were taken during David's reigns to make the government of Scotland, or that part of Scotland that he administered, more like the government of Anglo-Norman England. New sheriffdoms enabled the King to effectively administer royal demesne land. During David I's reign, royal sheriffs had been established in the king's core personal territories; namely, in rough chronological order, at Roxburgh, Scone, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Stirling and Perth.[19] The Justiciarship too was created in David's reign. Two Justiciarships were created, one for Scotland-proper and one for Lothian, i.e. for Scotland north of the river Forth and Scotland south of the Forth and east of Galloway. Although this institution had Anglo-Norman origins, in Scotland north of the Forth at least it represented some form of continuity with an older office. For instance, Mormaer Causantín of Fife is styled judex magnus (i.e. great Brehon); the Justiciarship of Scotia hence was just as much a Gaelic office modified by Normanisation as it was an import, illustrating Barrow's "balance of New and Old" argument.[20]

David I and the economy

Silver penny of David I.

Alston mines

An important source of David's wealth during his career came from the revenue of his English earldom and the proceeds of the silver mines at Alston. Alston silver allowed David to indulge in the "regalian gratification" of his own coinage, and to continue his project of attempting to link royal power and economic expansion.[21] Building programmes depended to a large degree on disposable income; consumption of foreign and exotic commodities broadened; men of ability and ambition found their way to court and entered the service of the king. What is more, no less than the written word, the coin acted upon the culture and mental categories of people who made use of it. Like a seal displaying the king in majesty, the coin broadcast the image of the ruler to his people and, more fundamentally, altered the simple nature of trade.[22] Though coins were not absent from Scotland before David, these were by definition foreign objects, unseen and unused by most of the population. The arrival of a native coinage – no less than the arrival of towns, laws and charters – marked the penetration of the "Europeanizing" concepts of European culture into ever less "non-European" Scotland.

Creation of burghs

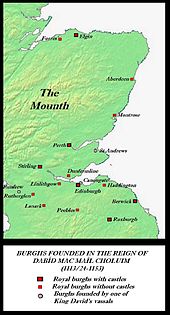

Burghs established in Scotland before the accession of David's successor and grandson, Máel Coluim IV; these were essentially Scotland-proper's first towns.

David was also a great town builder. In part, David made use of the "English" income secured for him by his marriage to Matilda de Senlis in order to finance the construction of the first true towns in Scotland, and these in turn allowed the establishment of several more.[23] As Prince of the Cumbrians, David founded the first two burghs of "Scotland", at Roxburgh and Berwick.[24] These were settlements with defined boundaries and guaranteed trading rights, locations where the king could collect and sell the products of his cain and conveth (a payment made in lieu of providing the king hospitality) rendered to him. These burghs were essentially Scotland's first towns.[25] David would found more of these burghs when he became King of Scots. Before 1135, David laid the foundations of four more burghs, this time in the new territory he had acquired as King of Scots; burghs were founded at Stirling, Dunfermline and Edinburgh, three of David's favoured residences.[26] Around 15 burghs have their foundations traced to the reign of David I, although because of the sparsity of some of the evidence, this exact number is uncertain.[27]

Effect of the burghs

Perhaps nothing in David's reign compares in importance to this. No institution would do more to reshape the long-term economic and ethnic shape of Scotland than the burgh. These planned towns were or became English in culture and language; as William of Newburgh would write in the reign of King William the Lion, describing the persecution of English-speakers in Scotland, "the towns and burghs of the Scottish realm are known to be inhabited by English"[28] and the failure of these towns to go native would in the long term undermine the position of the Gaelic language and give birth to the idea of the Scottish Lowlands.[29]

The thesis that the "rise of towns" was indirectly responsible for the medieval flourishing of Europe has been accepted, at least in a circumscribed form, from the time of Henri Pirenne, a century ago.[30] Commerce generated by and the economic privileges granted to merchant towns across northern Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries paid for, in new revenues, the increasing diversification of society and ensured that further growth would occur. What was of great importance for the future of Scotland was the creation by David of perhaps seven such jurisdictionally licensed communities at ancient royal centers and even at new sites, the latter mainly along his eastern seaboard.[31] While this could not, at first, have amounted to much more than the nucleus of an immigrant merchant class making use of the established marketplace for the purpose of disposing of the purely local harvest, in both crop and chattels, there is a sense of profound expectation inherent in such foundations. Regional trade and international trade never lagged far behind the opening of the royal burgh to the world, and that most such burghs were kept in royal demesne meant that the king reserved the right to an excise on all transactions occurring within their bounds and to charge custom dues on those vessels taking berth in their harbours.[32]

Religious reform

The changes that David was most noted for at the time, however, were his religious changes. The reason for this is that practically all our sources were Reform-minded monks or clerics, grateful to David for his efforts. David's changes, or alleged changes, can be divided into two parts: monastic patronage and ecclesiastical restructuring.

Monastic patronage

The modern ruins of Kelso Abbey. This establishment was originally at Selkirk from 1113, but was moved to Kelso in 1128 to better serve David's southern "capital" at Roxburgh.

David was certainly at least one of medieval Scotland's greatest monastic patrons. In 1113, in perhaps David's first act as Prince of the Cumbrians, he founded Selkirk Abbey for the Tironensian Order. Several years later, perhaps in 1116, David visited Tiron itself, probably to acquire more monks; in 1128 he transferred Selkirk Abbey to Kelso, nearer Roxburgh, at this point his chief residence.[33] In 1144, David and Bishop John of Glasgow prompted Kelso Abbey to found a daughter house, Lesmahagow Priory.[34] David also continued his predecessor Alexander's patronage of the Augustinians, founding Holyrood Abbey with monks from Merton Priory. David and Bishop John, moreover, established Jedburgh Abbey with canons from Beauvais in 1138.[35] Other Augustinian foundations included St Andrew's Cathedral Priory, established by David and Bishop Robert of St Andrews in 1140, which in turn founded an establishment at Loch Leven (1150x1153); an Augustinian abbey, whose canons were taken from Arrouaise in France, was established by the year 1147 at Cambuskenneth near Stirling, another prominent royal centre.[36] However, by 23 March 1137 David had also turned his patronage towards the Cistercian Order, founding the famous Melrose Abbey from monks of Rievaulx.[37] Melrose would become the greatest medieval monastic establishment in Scotland south of the river Forth. It was from Melrose that David established Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, Kinloss Abbey in Moray, and Holmcultram Abbey in Cumberland.[38] David also, like Alexander, patronized Benedictines, introducing monks to Coldingham (a non-monastic property of Durham Priory) in 1139 and having making it a priory by 1149.[39] David's activities were paralleled by other "Scottish" magnates. For instance, the Premonstratensian house of Dryburgh Abbey was founded in 1150 by monks from Alnwick Abbey with the patronage of Hugh de Morville, Lord of Lauderdale.[40] Moreover, six years after the foundation of Melrose Abbey, King Fergus of Galloway likewise founded a Cistercian abbey from Rievaulx, Dundrennan Abbey, which would become a powerful landowner in both Galloway and Ireland and was known to Francesco Pegolotti as Scotland's richest abbey.[41]

The modern ruins of Melrose Abbey. Founded in 1137, this Cistercian monastery became one of David's greatest legacies.

Not only were such monasteries an expression of David's undoubted piety, but they also functioned to transform Scottish society. Monasteries became centres of foreign influence, being founded by French or English monks. They provided sources of literate men, able to serve the crown's growing administrative needs. This was particularly the case with the Augustinians.[42] Moreover, these new monasteries, and the Cistercian ones in particular, introduced new agricultural practices. In the words of one historian, the Cistercians were "pioneers or frontiersmen ... cultural revolutionaries, who carried new techniques of land management and new attitudes towards land exploitation".[43] Duncan calls Scotland's new Cistercian establishments "the largest and most significant contribution by David I to the religious life of the kingdom".[44] Cistercians equated spiritual health with economic achievement and environmental exploitation.[43] Cistercian labour transformed southern Scotland into one of northern Europe's main source of sheep wool.[45]

Bishopric of Glasgow

Almost as soon as he was in charge of the Cumbrian principality, David placed the bishopric of Glasgow under his chaplain, John, whom David may have met for the first time during his participation in Henry's conquest of Normandy after 1106.[46] John himself was closely associated with the Tironensian Order, and presumably committed to the new Gregorian ideas regarding episcopal organization. David carried out an inquest, afterwards assigned to the bishopric all the lands of his principality, except those in the east of his principality which were already governed by the Scotland-proper based bishop of St Andrews.[47] David was responsible for assigning to Glasgow enough lands directly to make the bishopric self-sufficient and for ensuring that in the longer term Glasgow would become the second most important bishopric in the Kingdom of Scotland. By the 1120s, work also began on building a proper cathedral for the diocese.[48] David would also try to ensure that his reinvigorated episcopal see would retain independence from other bishoprics, an aspiration which would generate a great deal of tension with the English church, where both the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York claimed overlordship.[49]

Church organization

It was once held that the Scotland's episcopal sees and entire parochial system owed its origins to the innovations of David I. Today, scholars have moderated this view. Although David moved the bishopric of Mortlach east to his new burgh of Aberdeen, and arranged the creation of the diocese of Caithness, no other bishoprics can be safely called David's creation.[50] The bishopric of Glasgow was restored rather than resurrected.[51] In the case of the Bishop of Whithorn, the resurrection of that see was the work of Thurstan, Archbishop of York, with King Fergus of Galloway and the cleric Gille Aldan.[52] That aside, Ailred of Rievaulx wrote in David's eulogy that when David came to power, "he found three or four bishops in the whole Scottish kingdom [north of the Forth], and the others wavering without a pastor to the loss of both morals and property; when he died, he left nine, both of ancient bishoprics which he himself restored, and new ones which he erected".[53] What is very likely is that, as well as preventing the long vacancies in bishoprics which had hitherto been common, David was at least partly responsible for forcing semi-monastic "bishoprics" like Brechin, Dunkeld, Mortlach (Aberdeen) and Dublane to become fully episcopal and firmly integrated into a national diocesan system.[54] As for the development of the parochial system, David's traditional role as its creator can not be sustained.[55] Scotland already had an ancient system of parish churches dating to the Early Middle Ages, and the kind of system introduced by David's Normanizing tendencies can more accurately be seen as mild refashioning, rather than creation; he made the Scottish system as a whole more like that of France and England, but he did not create it.[56]

Notes

^ Barrow, "The Balance of New and Old", pp. 9–11; Lynch, Scotland: A New History, p. 80.

^ Barrow, "The Balance of New and Old", p. 13.

^ Bartlett, The Making of Europe, pp. 24–59; Moore, The First European Revolution, c.970–1215, p. 30ff; see also Barrow, "The Balance of New and Old", passim, esp. 9; this idea of "Europe" seems in practice to mean "Western Europe".

^ Moore, The First European Revolution, c.970–1215, p. 30 ff; Haidu, The Subject Medieval/Modern, p. 156ff.; Bartlett, The Making of Europe, pp. 24–59, esp. 51–59. The idea of "Europe" would have been available to contemporaries of David, though the concept of "Christendom" would have been more familiar. This usage of "Europe" in the sense of a unified cultural entity is identified only by modern historians.

^ Moore, The First European Revolution, c.970–1215, pp. 38–45; Bartlett, The Making of Europe, p. 104.

^ G. Ladner, "Terms and ideas of renewal", pp. 1–33; C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, pp. 86, 92, 94–5, 149–50, 163–4; Bartlett, Making of Europe, pp. 243–68; Malcolm Barber, Two Cities, pp. 85–99

^ Robert Bartlett, "Turgot (c.1050–1115)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 , accessed 11 February 2007; William Forbes-Leith, Turgot, Life of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland, passim; Baker, "'A Nursery of Saints", pp. 129–132.

^ See, for instance, Dumville, "St Cathróe of Metz", pp. 172–188; Follett, Céli Dé in Ireland, pp. 1–8, 89–99.

^ John Watt, Church in Medieval Ireland, pp. 1–27; Veitch, "Replanting Paradise", pp. 136–66

^ Hudson, "Gaelic Princes and Gregorian Reform", pp. 61–82.

^ Barrow, "Beginnings of Military Feudalism", p. 250.

^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, p. 277.

^ Haidu, The Subject Medieval/Modern, p. 181; Moore, The First European Revolution, p. 57: "The requirement of tithe...defined the community dependent on each church, and endowed it with clear, universally known borders".

^ Barrow, ‘Balance’, 9–11.

^ G.W.S. Barrow, The Acts of William I King of Scots 1165–1214 in Regesta Regum Scottorum, Volume II, (Edinburgh, 1971), no. 116, pp. 198–9; trs. of quote, "The Beginnings of Military Feudalism" in Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, 2nd Ed. (2003), p. 252.

^ See Barrow, "The Beginnings of Military Feudalism", p. 252, n. 16, citing T. Forssner, Continental Germanic Personal Names in England, (Uppsala, 1916), p. 95; J. Mansion, Oud-Gentsche Naamkunde, (1924), p. 217; and G. White (ed.), Complete Peerage, vol. xii, pt. I, p. 537, n. d.

^ G.W.S. Barrow, "Badenoch and Strathspey, 1130–1312: 1. Secular and Political" in Northern Scotland, 8 (1988), p. 3.

^ See Richard Oram, "David I and the Conquest of Moray", p. & n. 43; see also, L. Toorians, "Twelfth-century Flemish Settlement in Scotland", pp. 1–14.

^ McNeill & MacQueen, Atlas of Scottish History p. 193

^ See Barrow, G.W.S., "The Judex", in Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 57–67 and "The Justiciar", also in Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, pp. 68–111.

^ Norman Davies, The Isles: A History, Sec. 4, p. 85 [photo]; Oram, David I: The King Who Made Scotland, p. 193ff; Bartlett, The Making of Europe, p. 287. To put the true importance of David’s silver in perspective, consider this comment of Ian Blanchard, "Lothian and Beyond: The Economy of the ‘English Empire’ of David I", p.29: "The discovery of [silver at Alston in] 1133 marked the beginnings of the first great regional mining boom which was at its height in c. 1136–8 yielded an output of some three or four tones of silver a year, or some ten times more than had been produced in the whole of Europe during any year of the past three-quarters of a millennium". Gold was essentially reserved for religion.

^ Oram, David I: The King Who Made Scotland, pp. 193, 195; Bartlett, The Making of Europe, p. 287: "The minting of coins and the issue of written dispositions changed the political culture of the societies in which the new practices appeared".

^ Oram, 192.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, p. 465.

^ See G.W.S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306, (Edinburgh. 1981), pp. 84–104; see also, Keith J. Stringer, "The Emergence of a Nation-State, 1100–1300", in Jenny Wormald (ed.), Scotland: A History, (Oxford, 2005), pp. 66–9.

^ Duncan, p. 265.

^ Stringer, "The Emergence of a Nation-State", p. 67. Regarding the uncertainty of numbers, Perth may date to the reign of Alexander I; Inverness is a case were the foundation may date later, but may date to the period of David I: see for instance the blanket statement that Inverness dates to David I's reign in Derek Hall, Burgess, Merchant and Priest: Burgh Life in the Medieval Scottish Town, (Edinburgh, 2002), compare Richard Oram, David I: The King Who Made Scotland, p. 93, where it is acknowledged that this is merely a possibility, to A.A.M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, p. 480, who quotes a charter indicating that the burgh dates to the reign of William the Lion.

^ A.O. Anderson, Scottish Annals, p. 256.

^ Stringer, "The Emergence of a Nation-State", 1100–1300", p. 67; Michael Lynch, Scotland: A New History, pp. 64–6; Thomas Owen Clancy, "History of Gaelic", here

^ Henri Pirenne, Medieval cities: their origins and the revival of trade, trans. F.D. Halsey, (Princeton, 1925); Barrow, "The Balance of New and Old", p. 6.

^ Oram, David I, pp. 80–82; Bartlett, The Making of Europe, pp. 176–177: "Scottish urban law originally derived from Newcastle upon Tyne". Early Scottish towns (p. 181) had mainly English immigrant populations.

^ Bartlett, The Making of Europe, p. 176: "Princes wanted towns, because they were profitable..."

^ Oram, David I: The King Who Made Scotland, p. 62; Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, pp. 145.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, pp. 145, 150.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, p. 150.

^ A.A.M. Duncan, "The Foundation of St Andrews Cathedral Priory, 1140", pp. 25, 27–8.

^ Richard Fawcett & Richard Oram, Melrose Abbey, p. 20.

^ Fawcett & Oram, Melrose Abbey, illus 1, p. 15.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, pp. 146–7.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, pp. 150–1.

^ Keith J. Stringer, "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", .pp. 128–9; Keith J. Stringer, The Reformed Church in Medieval Galloway and Cumbria, pp. 11, 35.

^ Peter Yeoman, Medieval Scotland, p. 15.

^ ab Fawcett & Oram, Melrose Abbey, p. 17.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, p. 148.

^ See, for instance, Stringer, The Reformed Church in Medieval Galloway and Cumbria, pp. 9–11.

^ Oram, David: The King Who Made Scotland, p. 62.

^ To a certain extent, the boundaries of David's Cumbrian Principality are conjecture on the basis of the boundaries of the diocese of Glasgow; Oram, David: The King Who Made Scotland, pp. 67–8.

^ G. W. S. Barrow, "King David I and Glasgow", pp. 208–9.

^ Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, pp. 257–9.

^ Oram, p. 158; Duncan, Making, p. 257–60; see also Gordon Donaldson, "Scottish Bishop's Sees", pp. 106–17.

^ Shead, "Origins of the Medieval Diocese of Glasgow", pp. 220–5.

^ Oram, Lordship of Galloway, p. 173.

^ A. O. Anderson, Scottish Annals, p. 233.

^ Barrow, Kingship and Unity, pp. 67–8

^ Ian B. Cowan wrote that "the principle steps were taken during the reign of David I": Ian B. Cowan, "Development of the Parochial System", p. 44.

^ Thomas Owen Clancy, "Annat and the Origins of the Parish", in the Innes Review, vol. 46, no. 2 (1995), pp. 91–115.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Primary sources

Anderson, Alan Orr (ed.), Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500–1286, 2 Vols, (Edinburgh, 1922)- Anderson, Alan Orr (ed.), Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers: AD 500–1286, (London, 1908), republished, Marjorie Anderson (ed.) (Stamford, 1991)

Barrow, G. W. S. (ed.), The Acts of Malcolm IV King of Scots 1153–1165, Together with Scottish Royal Acts Prior to 1153 not included in Sir Archibald Lawrie's '"Early Scottish Charters' , in Regesta Regum Scottorum, Volume I, (Edinburgh, 1960), introductory text, pp. 3–128- Barrow, G. W. S. (ed.), The Acts of William I King of Scots 1165–1214 in Regesta Regum Scottorum, Volume II, (Edinburgh, 1971)

- Barrow, G. W. S. (ed.), The Charters of King David I: The Written acts of David I King of Scots, 1124–1153 and of His Son Henry Earl of Northumberland, 1139–1152, (Woodbridge, 1999)

- Lawrie, Sir Archibald (ed.), Early Scottish Charters Prior to A.D. 1153, (Glasgow, 1905)

- Forbes-Leith, William (ed.), Turgot, Life of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland, (Edinburgh, 1884)

- MacQueen, John, MacQueen, Winifred and Watt, D. E. R., (eds.), Scotichronicon by Walter Bower, vol. 3, (Aberdeen, 1995)

- Skene, Felix J. H. (tr.) & Skene, William F. (ed.), John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, (Edinburgh, 1872)

Secondary sources

Barber, Malcolm, The Two Cities: Medieval Europe, 1050–1320, (London, 1992)- Barrow, G. W. S. (ed.), The Acts of Malcolm IV King of Scots 1153–1165, Together with Scottish Royal Acts Prior to 1153 not included in Sir Archibald Lawrie's '"Early Scottish Charters' in Regesta Regum Scottorum, Volume I, (Edinburgh, 1960), introductory text, pp. 3–128

- Barrow, G. W. S., "Beginnings of Military Feudalism", in G. W. S. Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 250–78

- Barrow, G. W. S., "David I (c.1085–1153)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2006 , accessed 11 February 2007

- Barrow, G. W. S., "David I of Scotland: The Balance of New and Old", in G. W. S. Barrow (ed.), Scotland and Its Neighbours in the Middle Ages, (London, 1992), pp. 45–65, originally published as the 1984 Stenton Lecture, (Reading, 1985)

- Barrow, G.W.S., "The Judex", in G. W. S. Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 57–67

- Barrow, G.W.S. "The Justiciar", in G. W. S. Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 68–111

- Barrow, G. W. S., Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306, (Edinburgh. 1981)

- Barrow, G. W. S., "Malcolm III (d. 1093)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 , accessed 3 February 2007

- Barrow, G. W. S., "The Royal House and the Religious Orders", in G.W.S. Barrow (ed.), The Kingdom of the Scots, (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 151–68

Bartlett, Robert, England under the Norman and Angevin Kings, 1075–1225, (Oxford, 2000)- Bartlett, Robert, The Making of Europe, Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change: 950–1350, (London, 1993)

- Bartlett, Robert, "Turgot (c.1050–1115)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 , accessed 11 February 2007

- Blanchard, Ian., "Lothian and Beyond: The Economy of the ‘English Empire’ of David I", in Richard Britnell and John Hatcher (eds.), Progress and Problems in Medieval England: Essays in Honour of Edward Miller, (Cambridge, 1996)

- Boardman, Steve, "Late Medieval Scotland and the Matter of Britain", in Edward J. Cowan and Richard J. Finlay (eds.), Scottish History: The Power of the Past, (Edinburgh, 2002), pp. 47–72

- Cowan, Edward J., "The Invention of Celtic Scotland", in Edward J. Cowan & R. Andrew McDonald (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, (East Lothian, 2000), pp. 1–23

- Dalton, Paul, "Scottish Influence on Durham, 1066–1214", in David Rollason, Margaret Harvey & Michael Prestwich (eds.), Anglo-Norman Durham, 1093–1193, pp. 339–52

Davies, Norman, The Isles: A History, (London, 1999)

Davies, R. R., Domination and Conquest: The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 1100–1300, (Cambridge, 1990)- Davies. R. R., The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles, 1093–1343, (Oxford, 2000)

Dowden, John, The Bishops of Scotland, ed. J. Maitland Thomson, (Glasgow, 1912)

Dumville, David N., "St Cathróe of Metz and the Hagiography of Exoticism", in John Carey et al. (eds.), Irish Hagiography: Saints and Scholars, (Dublin, 2001), pp. 172–188

Duncan, A. A. M., "The Foundation of St Andrews Cathedral Priory, 1140", in The Scottish Historical Review, vol 84, (April, 2005), pp. 1–37- Duncan, A. A. M., The Kingship of the Scots 842–1292: Succession and Independence, (Edinburgh, 2002)

- Duncan, A. A. M., Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, (Edinburgh, 1975)

- Fawcetts, Richard, & Oram, Richard, Melrose Abbey, (Stroud, 2004)

- Follett, Wesley, Céli Dé in Ireland: Monastic Writing and Identity in the Early Middle Ages, (Woodbridge, 2006)

- Green, Judith A., "Anglo-Scottish Relations, 1066–1174", in Michael Jones and Malcolm Vale (eds.), England and Her Neigh-bours: Essays in Honour of Pierre Chaplais (London, 1989)

- Green, Judith A., "David I and Henry I", in the Scottish Historical Review. vol. 75 (1996), pp. 1–19

- Haidu, Peter, The Subject Medieval/Modern: Text and Governance in the Middle Ages, (Stamford, 2004)

- Hall, Derek, Burgess, Merchant and Priest: Burgh Life in the Medieval Scottish Town, (Edinburgh, 2002)

- Hammond, Matthew H., "Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish history", in The Scottish Historical Review, 85 (2006), pp. 1–27

- Hudson, Benjamin T., "Gaelic Princes and Gregorian Reform", in Benjamin T. Hudson and Vickie Ziegler (eds.), Crossed Paths: Methodological Approaches to the Celtic Aspects of the European Middle Ages, (Lanham, 1991), pp. 61–81

Jackson, Kenneth, The Gaelic Notes in the Book of Deer: The Osborn Bergin Memorial Lecture 1970, (Cambridge, 1972)- Ladner, G., "Terms and Ideas of Renewal", in Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable and Carol D. Lanham(eds.), Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century, (Oxford, 1982), pp. 1–33

- Lang, Andrew, A History of Scotland from the Roman Occupation, 2 vols, vol. 1, (Edinburgh, 1900)

- Lawrence, C. H., Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages, 2nd edition, (London, 1989)

- Lynch, Michael, Scotland: A New History, (Edinburgh, 1991)

- McNeill, Peter G. B. & MacQueen, Hector L. (eds), Atlas of Scottish History to 1707, (Edinburgh, 1996)

- Moore, R. I., The First European Revolution, c.970–1215, (Cambridge, 2000)

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí, Early Medieval Ireland: 400–1200, (Harlow, 1995)

Oram, Richard, David: The King Who Made Scotland, (Gloucestershire, 2004)- Oram, Richard, The Lordship of Galloway, (Edinburgh, 2000)

- Pirenne, Henri, Medieval cities: their origins and the revival of trade, trans. F.D. Halsey, (Princeton, 1925)

- Pittock, Murray G.H,. Celtic Identity and the British Image, (Manchester, 1999)

- Ritchie, Græme, The Normans in Scotland, (Edinburgh, 1954)

- Skene, William F., Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban, 3 vols., (Edinburgh, 1876–80)

- Stringer, Keith J. , "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", in Edward J. Cowan & R. Andrew McDonald (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, (East Lothian, 2000), .pp. 127–65

- Stringer, Keith J., The Reformed Church in Medieval Galloway and Cumbria: Contrasts, Connections and Continuities (The Eleventh Whithorn Lecture, 14 September 2002), (Whithorn, 2003)

- Stringer, Keith J., "State-Building in Twelfth-Century Britain: David I, King of Scots, and Northern England", in John C. Appleby and Paul Dalton (eds.), Government, Religion, and Society in Northern England, 1000–1700. (Stroud, 1997)

- Stringer, Keith J., The Reign of Stephen: Kingship, Warfare and Government in Twelfth-Century England, (London, 1993)

- Toorians, L., "Twelfth-century Flemish Settlement in Scotland", in Grant G. Simpson (ed.), Scotland and the Low Countries, 1124–1994, (East Linton, 1996), pp. 1–14

- Veitch, Kenneth, "'Replanting Paradise':Alexander I and the Reform of Religious Life in Scotland", in the Innes Review, 52 (2001), pp. 136–166

- Watt, John, Church in Medieval Ireland, (Dublin, 1972)

- Yeoman, Peter, Medieval Scotland: An Archaeological Perspective, (London, 1995)