Tetrahedron

| Regular tetrahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) | |

| Type | Platonic solid |

| Elements | F = 4, E = 6 V = 4 (χ = 2) |

| Faces by sides | 43 |

| Conway notation | T |

| Schläfli symbols | 3,3 |

| h4,3, s2,4, sr2,2 | |

| Face configuration | V3.3.3 |

| Wythoff symbol | 3 | 2 3 | 2 2 2 |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry | Td, A3, [3,3], (*332) |

| Rotation group | T, [3,3]+, (332) |

| References | U01, C15, W1 |

| Properties | regular, convexdeltahedron |

| Dihedral angle | 70.528779° = arccos(1/3) |

3.3.3 (Vertex figure) |  Self-dual (dual polyhedron) |

Net | |

Tetrahedron (Matemateca IME-USP)

In geometry, a tetrahedron (plural: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, six straight edges, and four vertex corners. The tetrahedron is the simplest of all the ordinary convex polyhedra and the only one that has fewer than 5 faces.[1]

The tetrahedron is the three-dimensional case of the more general concept of a Euclidean simplex, and may thus also be called a 3-simplex.

The tetrahedron is one kind of pyramid, which is a polyhedron with a flat polygon base and triangular faces connecting the base to a common point. In the case of a tetrahedron the base is a triangle (any of the four faces can be considered the base), so a tetrahedron is also known as a "triangular pyramid".

Like all convex polyhedra, a tetrahedron can be folded from a single sheet of paper. It has two such nets.[1]

For any tetrahedron there exists a sphere (called the circumsphere) on which all four vertices lie, and another sphere (the insphere) tangent to the tetrahedron's faces.[2]

Contents

1 Regular tetrahedron

1.1 Formulas for a regular tetrahedron

1.2 Isometries of the regular tetrahedron

1.3 Orthogonal projections of the regular tetrahedron

1.4 Cross section of regular tetrahedron

1.5 Spherical tiling

2 Other special cases

2.1 Isometries of irregular tetrahedra

3 General properties

3.1 Volume

3.1.1 Heron-type formula for the volume of a tetrahedron

3.1.2 Volume divider

3.1.3 Non-Euclidean volume

3.2 Distance between the edges

3.3 Properties analogous to those of a triangle

3.4 Geometric relations

3.5 A law of sines for tetrahedra and the space of all shapes of tetrahedra

3.6 Law of cosines for tetrahedra

3.7 Interior point

3.8 Inradius

3.9 Circumradius

3.10 Faces

4 Integer tetrahedra

5 Related polyhedra and compounds

6 Applications

6.1 Numerical analysis

6.2 Chemistry

6.3 Electricity and electronics

6.4 Games

6.5 Color space

6.6 Contemporary art

6.7 Popular culture

6.8 Geology

6.9 Structural engineering

6.10 Aviation

7 Tetrahedral graph

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Regular tetrahedron

A regular tetrahedron is one in which all four faces are equilateral triangles. It is one of the five regular Platonic solids, which have been known since antiquity.

In a regular tetrahedron, all faces are the same size and shape (congruent) and all edges are the same length.

Five tetrahedra are laid flat on a plane, with the highest 3-dimensional points marked as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. These points are then attached to each other and a thin volume of empty space is left, where the five edge angles do not quite meet.

Regular tetrahedra alone do not tessellate (fill space), but if alternated with regular octahedra in the ratio of two tetrahedra to one octahedron, they form the alternated cubic honeycomb, which is a tessellation.

The regular tetrahedron is self-dual, which means that its dual is another regular tetrahedron. The compound figure comprising two such dual tetrahedra form a stellated octahedron or stella octangula.

Formulas for a regular tetrahedron

The following Cartesian coordinates define the four vertices of a tetrahedron with edge length 2, centered at the origin, and two level edges:

- (±1,0,−12)and(0,±1,12)displaystyle left(pm 1,0,-frac 1sqrt 2right)quad mboxandquad left(0,pm 1,frac 1sqrt 2right)

Expressed symmetrically as 4 points on the unit sphere, centroid at the origin, with lower face level, the vertices are:

v1 = ( sqrt(8/9), 0, -1/3 )

v2 = ( -sqrt(2/9), sqrt(2/3), -1/3 )

v3 = ( -sqrt(2/9), -sqrt(2/3), -1/3 )

v4 = ( 0, 0, 1 )

with the edge length of sqrt(8/3).

Still another set of coordinates are based on an alternated cube or demicube with edge length 2. This form has Coxeter diagram ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() and Schläfli symbol h4,3. The tetrahedron in this case has edge length 2√2. Inverting these coordinates generates the dual tetrahedron, and the pair together form the stellated octahedron, whose vertices are those of the original cube.

and Schläfli symbol h4,3. The tetrahedron in this case has edge length 2√2. Inverting these coordinates generates the dual tetrahedron, and the pair together form the stellated octahedron, whose vertices are those of the original cube.

- Tetrahedron: (1,1,1), (1,−1,−1), (−1,1,−1), (−1,−1,1)

- Dual tetrahedron: (−1,−1,−1), (−1,1,1), (1,−1,1), (1,1,−1)

Regular tetrahedron ABCD and its circumscribed sphere

For a regular tetrahedron of edge length a:

| Face area | A0=34a2displaystyle A_0=frac sqrt 34a^2,  |

Surface area[3] | A=4A0=3a2displaystyle A=4,A_0=sqrt 3a^2,  |

| Height of pyramid[4] | h=63a=23adisplaystyle h=frac sqrt 63a=sqrt frac 23,a,  |

| Edge to opposite edge distance | l=12adisplaystyle l=frac 1sqrt 2,a,  |

Volume[3] | V=13A0h=212a3=a362displaystyle V=frac 13A_0h=frac sqrt 212a^3=frac a^36sqrt 2,  |

| Face-vertex-edge angle | arccos(13)=arctan(2)displaystyle arccos left(frac 1sqrt 3right)=arctan left(sqrt 2right),  (approx. 54.7356°) |

Face-edge-face angle, i.e., "dihedral angle"[3] | arccos(13)=arctan(22)displaystyle arccos left(frac 13right)=arctan left(2sqrt 2right),  (approx. 70.5288°) |

| Edge central angle,[5][6] known as the tetrahedral angle, as it is the bond angle in a tetrahedral molecule. It is also the angle between Plateau borders at a vertex. | arccos(−13)=2arctan(2)displaystyle arccos left(-frac 13right)=2arctan left(sqrt 2right),  (approx. 109.4712°) |

Solid angle at a vertex subtended by a face | arccos(2327)displaystyle arccos left(frac 2327right)  (approx. 0.55129 steradians) (approx. 1809.8 square degrees) |

| Radius of circumsphere[3] | R=64a=38adisplaystyle R=frac sqrt 64a=sqrt frac 38,a,  |

| Radius of insphere that is tangent to faces[3] | r=13R=a24displaystyle r=frac 13R=frac asqrt 24,  |

| Radius of midsphere that is tangent to edges[3] | rM=rR=a8displaystyle r_mathrm M =sqrt rR=frac asqrt 8,  |

| Radius of exspheres | rE=a6displaystyle r_mathrm E =frac asqrt 6,  |

| Distance to exsphere center from the opposite vertex | dVE=62a=32adisplaystyle d_mathrm VE =frac sqrt 62a=sqrt frac 32a,  |

With respect to the base plane the slope of a face (2√2) is twice that of an edge (√2), corresponding to the fact that the horizontal distance covered from the base to the apex along an edge is twice that along the median of a face. In other words, if C is the centroid of the base, the distance from C to a vertex of the base is twice that from C to the midpoint of an edge of the base. This follows from the fact that the medians of a triangle intersect at its centroid, and this point divides each of them in two segments, one of which is twice as long as the other (see proof).

For a regular tetrahedron with side length a, radius R of its circumscribing sphere, and distances di from an arbitrary point in 3-space to its four vertices, we have[7]

- d14+d24+d34+d444+16R49=(d12+d22+d32+d424+2R23)2;4(a4+d14+d24+d34+d44)=(a2+d12+d22+d32+d42)2.displaystyle beginalignedfrac d_1^4+d_2^4+d_3^4+d_4^44+frac 16R^49&=left(frac d_1^2+d_2^2+d_3^2+d_4^24+frac 2R^23right)^2;\4left(a^4+d_1^4+d_2^4+d_3^4+d_4^4right)&=left(a^2+d_1^2+d_2^2+d_3^2+d_4^2right)^2.endaligned

Isometries of the regular tetrahedron

The proper rotations, (order-3 rotation on a vertex and face, and order-2 on two edges) and reflection plane (through two faces and one edge) in the symmetry group of the regular tetrahedron

The vertices of a cube can be grouped into two groups of four, each forming a regular tetrahedron (see above, and also animation, showing one of the two tetrahedra in the cube). The symmetries of a regular tetrahedron correspond to half of those of a cube: those that map the tetrahedra to themselves, and not to each other.

The tetrahedron is the only Platonic solid that is not mapped to itself by point inversion.

The regular tetrahedron has 24 isometries, forming the symmetry group Td, [3,3], (*332), isomorphic to the symmetric group, S4. They can be categorized as follows:

T, [3,3]+, (332) is isomorphic to alternating group, A4 (the identity and 11 proper rotations) with the following conjugacy classes (in parentheses are given the permutations of the vertices, or correspondingly, the faces, and the unit quaternion representation):- identity (identity; 1)

- rotation about an axis through a vertex, perpendicular to the opposite plane, by an angle of ±120°: 4 axes, 2 per axis, together 8 ((1 2 3), etc.; 1 ± i ± j ± k/2)

- rotation by an angle of 180° such that an edge maps to the opposite edge: 3 ((1 2)(3 4), etc.; i, j, k)

- reflections in a plane perpendicular to an edge: 6

- reflections in a plane combined with 90° rotation about an axis perpendicular to the plane: 3 axes, 2 per axis, together 6; equivalently, they are 90° rotations combined with inversion (x is mapped to −x): the rotations correspond to those of the cube about face-to-face axes

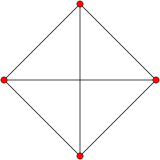

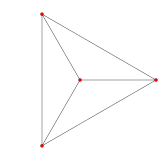

Orthogonal projections of the regular tetrahedron

The regular tetrahedron has two special orthogonal projections, one centered on a vertex or equivalently on a face, and one centered on an edge. The first corresponds to the A2Coxeter plane.

| Centered by | Face/vertex | Edge |

|---|---|---|

| Image |  |  |

| Projective symmetry | [3] | [4] |

Cross section of regular tetrahedron

A central cross section of a regular tetrahedron is a square.

The two skew perpendicular opposite edges of a regular tetrahedron define a set of parallel planes. When one of these planes intersects the tetrahedron the resulting cross section is a rectangle.[8] When the intersecting plane is near one of the edges the rectangle is long and skinny. When halfway between the two edges the intersection is a square. The aspect ratio of the rectangle reverses as you pass this halfway point. For the midpoint square intersection the resulting boundary line traverses every face of the tetrahedron similarly. If the tetrahedron is bisected on this plane, both halves become wedges.

A tetragonal disphenoid viewed orthogonally to the two green edges.

This property also applies for tetragonal disphenoids when applied to the two special edge pairs.

Spherical tiling

The tetrahedron can also be represented as a spherical tiling, and projected onto the plane via a stereographic projection. This projection is conformal, preserving angles but not areas or lengths. Straight lines on the sphere are projected as circular arcs on the plane.

|  |

Orthographic projection | Stereographic projection |

|---|

Other special cases

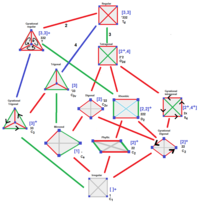

Tetrahedral symmetry subgroup relations |  Tetrahedral symmetries shown in tetrahedral diagrams |

An isosceles tetrahedron, also called a disphenoid, is a tetrahedron where all four faces are congruent triangles. A space-filling tetrahedron packs with congruent copies of itself to tile space, like the disphenoid tetrahedral honeycomb.

In a trirectangular tetrahedron the three face angles at one vertex are right angles. If all three pairs of opposite edges of a tetrahedron are perpendicular, then it is called an orthocentric tetrahedron. When only one pair of opposite edges are perpendicular, it is called a semi-orthocentric tetrahedron. An isodynamic tetrahedron is one in which the cevians that join the vertices to the incenters of the opposite faces are concurrent, and an isogonic tetrahedron has concurrent cevians that join the vertices to the points of contact of the opposite faces with the inscribed sphere of the tetrahedron.

Isometries of irregular tetrahedra

The isometries of an irregular (unmarked) tetrahedron depend on the geometry of the tetrahedron, with 7 cases possible. In each case a 3-dimensional point group is formed. Two other isometries (C3, [3]+), and (S4, [2+,4+]) can exist if the face or edge marking are included. Tetrahedral diagrams are included for each type below, with edges colored by isometric equivalence, and are gray colored for unique edges.

| Tetrahedron name | Edge equivalence diagram | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Symmetry | |||||

Schön. | Cox. | Orb. | Ord. | ||

| Regular Tetrahedron |  | Four equilateral trianglesIt forms the symmetry group Td, isomorphic to the symmetric group, S4. A regular tetrahedron has Coxeter diagram | |||

Td T | [3,3] [3,3]+ | *332 332 | 24 12 | ||

Triangular pyramid |  | An equilateral triangle base and three equal isosceles triangle sidesIt gives 6 isometries, corresponding to the 6 isometries of the base. As permutations of the vertices, these 6 isometries are the identity 1, (123), (132), (12), (13) and (23), forming the symmetry group C3v, isomorphic to the symmetric group, S3. A triangular pyramid has Schläfli symbol 3∨( ). | |||

C3v C3 | [3] [3]+ | *33 33 | 6 3 | ||

| Mirrored sphenoid | Two equal scalene triangles with a common base edgeThis has two pairs of equal edges (1,3), (1,4) and (2,3), (2,4) and otherwise no edges equal. The only two isometries are 1 and the reflection (34), giving the group Cs, also isomorphic to the cyclic group, Z2. | ||||

Cs =C1h =C1v | [ ] | * | 2 | ||

| Irregular tetrahedron (No symmetry) | Four unequal triangles Its only isometry is the identity, and the symmetry group is the trivial group. An irregular tetrahedron has Schläfli symbol ( )∨( )∨( )∨( ). | ||||

| C1 | [ ]+ | 1 | 1 | ||

Disphenoids (Four equal triangles) | |||||

Tetragonal disphenoid |  | Four equal isosceles triangles It has 8 isometries. If edges (1,2) and (3,4) are of different length to the other 4 then the 8 isometries are the identity 1, reflections (12) and (34), and 180° rotations (12)(34), (13)(24), (14)(23) and improper 90° rotations (1234) and (1432) forming the symmetry group D2d. A tetragonal disphenoid has Coxeter diagram | |||

D2d S4 | [2+,4] [2+,4+] | 2*2 2× | 8 4 | ||

Rhombic disphenoid | Four equal scalene triangles It has 4 isometries. The isometries are 1 and the 180° rotations (12)(34), (13)(24), (14)(23). This is the Klein four-group V4 or Z22, present as the point group D2. A rhombic disphenoid has Coxeter diagram | ||||

D2 | [2,2]+ | 222 | 4 | ||

Generalized disphenoids (2 pairs of equal triangles) | |||||

Digonal disphenoid |   | Two pairs of equal isosceles triangles. This gives two opposite edges (1,2) and (3,4) that are perpendicular but different lengths, and then the 4 isometries are 1, reflections (12) and (34) and the 180° rotation (12)(34). The symmetry group is C2v, isomorphic to the Klein four-group V4. A digonal disphenoid has Schläfli symbol ∨ . | |||

C2v C2 | [2] [2]+ | *22 22 | 4 2 | ||

| Phyllic disphenoid | Two pairs of equal scalene or isosceles triangles This has two pairs of equal edges (1,3), (2,4) and (1,4), (2,3) but otherwise no edges equal. The only two isometries are 1 and the rotation (12)(34), giving the group C2 isomorphic to the cyclic group, Z2. | ||||

C2 | [2]+ | 22 | 2 | ||

General properties

Volume

The volume of a tetrahedron is given by the pyramid volume formula:

- V=13A0hdisplaystyle V=frac 13A_0,h,

where A0 is the area of the base and h is the height from the base to the apex. This applies for each of the four choices of the base, so the distances from the apexes to the opposite faces are inversely proportional to the areas of these faces.

For a tetrahedron with vertices

a = (a1, a2, a3),

b = (b1, b2, b3),

c = (c1, c2, c3), and

d = (d1, d2, d3), the volume is 1/6|det(a − d, b − d, c − d)|, or any other combination of pairs of vertices that form a simply connected graph. This can be rewritten using a dot product and a cross product, yielding

- V=|(a−d)⋅((b−d)×(c−d))|6.displaystyle V=frac 6.

If the origin of the coordinate system is chosen to coincide with vertex d, then d = 0, so

- V=|a⋅(b×c)|6,displaystyle V=frac mathbf a cdot (mathbf b times mathbf c )6,

where a, b, and c represent three edges that meet at one vertex, and a · (b × c) is a scalar triple product. Comparing this formula with that used to compute the volume of a parallelepiped, we conclude that the volume of a tetrahedron is equal to 1/6 of the volume of any parallelepiped that shares three converging edges with it.

The absolute value of the scalar triple product can be represented as the following absolute values of determinants:

6⋅V=‖abc‖displaystyle 6cdot V=beginVmatrixmathbf a &mathbf b &mathbf c endVmatrixor 6⋅V=‖abc‖displaystyle 6cdot V=beginVmatrixmathbf a \mathbf b \mathbf c endVmatrix

where a=(a1,a2,a3)displaystyle mathbf a =(a_1,a_2,a_3),

is expressed as a row or column vector etc.

Hence

36⋅V2=|a2a⋅ba⋅ca⋅bb2b⋅ca⋅cb⋅cc2|displaystyle 36cdot V^2=beginvmatrixmathbf a^2 &mathbf a cdot mathbf b &mathbf a cdot mathbf c \mathbf a cdot mathbf b &mathbf b^2 &mathbf b cdot mathbf c \mathbf a cdot mathbf c &mathbf b cdot mathbf c &mathbf c^2 endvmatrixwhere a⋅b=abcosγdisplaystyle mathbf a cdot mathbf b =abcos gamma

etc.

which gives

- V=abc61+2cosαcosβcosγ−cos2α−cos2β−cos2γ,displaystyle V=frac abc6sqrt 1+2cos alpha cos beta cos gamma -cos ^2alpha -cos ^2beta -cos ^2gamma ,,

where α, β, γ are the plane angles occurring in vertex d. The angle α, is the angle between the two edges connecting the vertex d to the vertices b and c. The angle β, does so for the vertices a and c, while γ, is defined by the position of the vertices a and b.

Given the distances between the vertices of a tetrahedron the volume can be computed using the Cayley–Menger determinant:

- 288⋅V2=|0111110d122d132d1421d1220d232d2421d132d2320d3421d142d242d3420|displaystyle 288cdot V^2=beginvmatrix0&1&1&1&1\1&0&d_12^2&d_13^2&d_14^2\1&d_12^2&0&d_23^2&d_24^2\1&d_13^2&d_23^2&0&d_34^2\1&d_14^2&d_24^2&d_34^2&0endvmatrix

where the subscripts i, j ∈ 1, 2, 3, 4 represent the vertices a, b, c, d and dij is the pairwise distance between them – i.e., the length of the edge connecting the two vertices. A negative value of the determinant means that a tetrahedron cannot be constructed with the given distances. This formula, sometimes called Tartaglia's formula, is essentially due to the painter Piero della Francesca in the 15th century, as a three dimensional analogue of the 1st century Heron's formula for the area of a triangle.[9]

Denote a,b,c be three edges that meet at a point, and x,y,z the opposite edges. Let V be the volume of the tetrahedron; then[10]

- V=4a2b2c2−a2X2−b2Y2−c2Z2+XYZ12displaystyle V=frac sqrt 4a^2b^2c^2-a^2X^2-b^2Y^2-c^2Z^2+XYZ12

where

- X=b2+c2−x2displaystyle X=b^2+c^2-x^2

- Y=a2+c2−y2displaystyle Y=a^2+c^2-y^2

- Z=a2+b2−z2displaystyle Z=a^2+b^2-z^2

The above formula uses different expressions with the following formula,The above formula uses six lengths of edges, and the following formula uses three lengths of edges and three angles.

- V=abc61+2cosαcosβcosγ−cos2α−cos2β−cos2γdisplaystyle V=frac abc6sqrt 1+2cos alpha cos beta cos gamma -cos ^2alpha -cos ^2beta -cos ^2gamma

Heron-type formula for the volume of a tetrahedron

If U, V, W, u, v, w are lengths of edges of the tetrahedron (first three form a triangle; u opposite to U and so on), then[11]

- volume=(−a+b+c+d)(a−b+c+d)(a+b−c+d)(a+b+c−d)192uvwdisplaystyle textvolume=frac sqrt ,(-a+b+c+d),(a-b+c+d),(a+b-c+d),(a+b+c-d)192,u,v,w

where

- a=xYZb=yZXc=zXYd=xyzX=(w−U+v)(U+v+w)x=(U−v+w)(v−w+U)Y=(u−V+w)(V+w+u)y=(V−w+u)(w−u+V)Z=(v−W+u)(W+u+v)z=(W−u+v)(u−v+W).displaystyle beginaligneda&=sqrt xYZ\b&=sqrt yZX\c&=sqrt zXY\d&=sqrt xyz\X&=(w-U+v),(U+v+w)\x&=(U-v+w),(v-w+U)\Y&=(u-V+w),(V+w+u)\y&=(V-w+u),(w-u+V)\Z&=(v-W+u),(W+u+v)\z&=(W-u+v),(u-v+W).endaligned

Volume divider

A plane that divides two opposite edges of a tetrahedron in a given ratio also divides the volume of the tetrahedron in the same ratio. Thus any plane containing a bimedian (connector of opposite edges' midpoints) of a tetrahedron bisects the volume of the tetrahedron.[12][13]:pp.89–90

Non-Euclidean volume

For tetrahedra in hyperbolic space or in three-dimensional elliptic geometry, the dihedral angles of the tetrahedron determine its shape and hence its volume. In these cases, the volume is given by the Murakami–Yano formula.[14] However, in Euclidean space, scaling a tetrahedron changes its volume but not its dihedral angles, so no such formula can exist.

Distance between the edges

Any two opposite edges of a tetrahedron lie on two skew lines, and the distance between the edges is defined as the distance between the two skew lines. Let d be the distance between the skew lines formed by opposite edges a and b − c as calculated here. Then another volume formula is given by

- V=d|(a×(b−c))|6.displaystyle V=frac (mathbf a times mathbf (b-c) )6.

Properties analogous to those of a triangle

The tetrahedron has many properties analogous to those of a triangle, including an insphere, circumsphere, medial tetrahedron, and exspheres. It has respective centers such as incenter, circumcenter, excenters, Spieker center and points such as a centroid. However, there is generally no orthocenter in the sense of intersecting altitudes.[15]

Gaspard Monge found a center that exists in every tetrahedron, now known as the Monge point: the point where the six midplanes of a tetrahedron intersect. A midplane is defined as a plane that is orthogonal to an edge joining any two vertices that also contains the centroid of an opposite edge formed by joining the other two vertices. If the tetrahedron's altitudes do intersect, then the Monge point and the orthocenter coincide to give the class of orthocentric tetrahedron.

An orthogonal line dropped from the Monge point to any face meets that face at the midpoint of the line segment between that face's orthocenter and the foot of the altitude dropped from the opposite vertex.

A line segment joining a vertex of a tetrahedron with the centroid of the opposite face is called a median and a line segment joining the midpoints of two opposite edges is called a bimedian of the tetrahedron. Hence there are four medians and three bimedians in a tetrahedron. These seven line segments are all concurrent at a point called the centroid of the tetrahedron.[16] In addition the four medians are divided in a 3:1 ratio by the centroid (see Commandino's theorem). The centroid of a tetrahedron is the midpoint between its Monge point and circumcenter. These points define the Euler line of the tetrahedron that is analogous to the Euler line of a triangle.

The nine-point circle of the general triangle has an analogue in the circumsphere of a tetrahedron's medial tetrahedron. It is the twelve-point sphere and besides the centroids of the four faces of the reference tetrahedron, it passes through four substitute Euler points, one third of the way from the Monge point toward each of the four vertices. Finally it passes through the four base points of orthogonal lines dropped from each Euler point to the face not containing the vertex that generated the Euler point.[17]

The center T of the twelve-point sphere also lies on the Euler line. Unlike its triangular counterpart, this center lies one third of the way from the Monge point M towards the circumcenter. Also, an orthogonal line through T to a chosen face is coplanar with two other orthogonal lines to the same face. The first is an orthogonal line passing through the corresponding Euler point to the chosen face. The second is an orthogonal line passing through the centroid of the chosen face. This orthogonal line through the twelve-point center lies midway between the Euler point orthogonal line and the centroidal orthogonal line. Furthermore, for any face, the twelve-point center lies at the midpoint of the corresponding Euler point and the orthocenter for that face.

The radius of the twelve-point sphere is one third of the circumradius of the reference tetrahedron.

There is a relation among the angles made by the faces of a general tetrahedron given by [18]

- |−1cos(α12)cos(α13)cos(α14)cos(α12)−1cos(α23)cos(α24)cos(α13)cos(α23)−1cos(α34)cos(α14)cos(α24)cos(α34)−1|=0displaystyle beginvmatrix-1&cos (alpha _12)&cos (alpha _13)&cos (alpha _14)\cos (alpha _12)&-1&cos (alpha _23)&cos (alpha _24)\cos (alpha _13)&cos (alpha _23)&-1&cos (alpha _34)\cos (alpha _14)&cos (alpha _24)&cos (alpha _34)&-1\endvmatrix=0,

where αij is the angle between the faces i and j.

Geometric relations

A tetrahedron is a 3-simplex. Unlike the case of the other Platonic solids, all the vertices of a regular tetrahedron are equidistant from each other (they are the only possible arrangement of four equidistant points in 3-dimensional space).

A tetrahedron is a triangular pyramid, and the regular tetrahedron is self-dual.

A regular tetrahedron can be embedded inside a cube in two ways such that each vertex is a vertex of the cube, and each edge is a diagonal of one of the cube's faces. For one such embedding, the Cartesian coordinates of the vertices are

- (+1, +1, +1);

- (−1, −1, +1);

- (−1, +1, −1);

- (+1, −1, −1).

This yields a tetrahedron with edge-length 2√2, centered at the origin. For the other tetrahedron (which is dual to the first), reverse all the signs. These two tetrahedra's vertices combined are the vertices of a cube, demonstrating that the regular tetrahedron is the 3-demicube.

The stella octangula.

The volume of this tetrahedron is one-third the volume of the cube. Combining both tetrahedra gives a regular polyhedral compound called the compound of two tetrahedra or stella octangula.

The interior of the stella octangula is an octahedron, and correspondingly, a regular octahedron is the result of cutting off, from a regular tetrahedron, four regular tetrahedra of half the linear size (i.e., rectifying the tetrahedron).

The above embedding divides the cube into five tetrahedra, one of which is regular. In fact, five is the minimum number of tetrahedra required to compose a cube.

Inscribing tetrahedra inside the regular compound of five cubes gives two more regular compounds, containing five and ten tetrahedra.

Regular tetrahedra cannot tessellate space by themselves, although this result seems likely enough that Aristotle claimed it was possible. However, two regular tetrahedra can be combined with an octahedron, giving a rhombohedron that can tile space.

However, several irregular tetrahedra are known, of which copies can tile space, for instance the disphenoid tetrahedral honeycomb. The complete list remains an open problem.[19]

If one relaxes the requirement that the tetrahedra be all the same shape, one can tile space using only tetrahedra in many different ways. For example, one can divide an octahedron into four identical tetrahedra and combine them again with two regular ones. (As a side-note: these two kinds of tetrahedron have the same volume.)

The tetrahedron is unique among the uniform polyhedra in possessing no parallel faces.

A law of sines for tetrahedra and the space of all shapes of tetrahedra

A corollary of the usual law of sines is that in a tetrahedron with vertices O, A, B, C, we have

- sin∠OAB⋅sin∠OBC⋅sin∠OCA=sin∠OAC⋅sin∠OCB⋅sin∠OBA.displaystyle sin angle OABcdot sin angle OBCcdot sin angle OCA=sin angle OACcdot sin angle OCBcdot sin angle OBA.,

One may view the two sides of this identity as corresponding to clockwise and counterclockwise orientations of the surface.

Putting any of the four vertices in the role of O yields four such identities, but at most three of them are independent: If the "clockwise" sides of three of them are multiplied and the product is inferred to be equal to the product of the "counterclockwise" sides of the same three identities, and then common factors are cancelled from both sides, the result is the fourth identity.

Three angles are the angles of some triangle if and only if their sum is 180° (π radians). What condition on 12 angles is necessary and sufficient for them to be the 12 angles of some tetrahedron? Clearly the sum of the angles of any side of the tetrahedron must be 180°. Since there are four such triangles, there are four such constraints on sums of angles, and the number of degrees of freedom is thereby reduced from 12 to 8. The four relations given by this sine law further reduce the number of degrees of freedom, from 8 down to not 4 but 5, since the fourth constraint is not independent of the first three. Thus the space of all shapes of tetrahedra is 5-dimensional.[20]

Law of cosines for tetrahedra

Let P1 ,P2, P3, P4 be the points of a tetrahedron. Let Δi be the area of the face opposite vertex Pi and let θij be the dihedral angle between the two faces of the tetrahedron adjacent to the edge PiPj.

The law of cosines for this tetrahedron,[21] which relates the areas of the faces of the tetrahedron to the dihedral angles about a vertex, is given by the following relation:

- Δi2=Δj2+Δk2+Δl2−2(ΔjΔkcosθil+ΔjΔlcosθik+ΔkΔlcosθij)displaystyle Delta _i^2=Delta _j^2+Delta _k^2+Delta _l^2-2(Delta _jDelta _kcos theta _il+Delta _jDelta _lcos theta _ik+Delta _kDelta _lcos theta _ij)

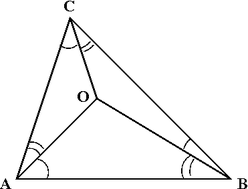

Interior point

Let P be any interior point of a tetrahedron of volume V for which the vertices are A, B, C, and D, and for which the areas of the opposite faces are Fa, Fb, Fc, and Fd. Then[22]:p.62,#1609

- PA⋅Fa+PB⋅Fb+PC⋅Fc+PD⋅Fd≥9V.displaystyle PAcdot F_mathrm a +PBcdot F_mathrm b +PCcdot F_mathrm c +PDcdot F_mathrm d geq 9V.

For vertices A, B, C, and D, interior point P, and feet J, K, L, and M of the perpendiculars from P to the faces,[22]:p.226,#215

- PA+PB+PC+PD≥3(PJ+PK+PL+PM).displaystyle PA+PB+PC+PDgeq 3(PJ+PK+PL+PM).

Inradius

Denoting the inradius of a tetrahedron as r and the inradii of its triangular faces as ri for i = 1, 2, 3, 4, we have[22]:p.81,#1990

- 1r12+1r22+1r32+1r42≤2r2,displaystyle frac 1r_1^2+frac 1r_2^2+frac 1r_3^2+frac 1r_4^2leq frac 2r^2,

with equality if and only if the tetrahedron is regular.

If A1, A2, A3 and A4 denote the area of each faces, the value of r is given by

r=3VA1+A2+A3+A4displaystyle r=frac 3VA_1+A_2+A_3+A_4.

This formula is obtained from dividing the tetrahedron into four tetrahedra whose points are the three points of one of the original faces and the incenter. Since the four subtetrahedra fill the volume, we have V=13A1r+13A2r+13A3r+13A4rdisplaystyle V=frac 13A_1r+frac 13A_2r+frac 13A_3r+frac 13A_4r

Circumradius

Denote the circumradius of a tetrahedron as R. Let a,b,c be the length of the three edges that meet at a point, and A,B,C the length of the opposite edges. Let V be the volume of the tetrahedron. Then[23][24]

- R=(aA+bB+cC)(aA+bB−cC)(aA−bB+cC)(−aA+bB+cC)24V.displaystyle R=frac sqrt (aA+bB+cC)(aA+bB-cC)(aA-bB+cC)(-aA+bB+cC)24V.

Faces

The sum of the areas of any three faces is greater than the area of the fourth face.[22]:p.225,#159

Integer tetrahedra

There exist tetrahedra having integer-valued edge lengths, face areas and volume. One example has one edge of 896, the opposite edge of 990 and the other four edges of 1073; two faces have areas of 7005436800000000000♠436800 and the other two have areas of 7004471200000000000♠47120, while the volume is 7007620928000000000♠62092800.[25]:p.107

A tetrahedron can have integer volume and consecutive integers as edges, an example being the one with edges 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 and volume 48.[25]:p. 107

Related polyhedra and compounds

A regular tetrahedron can be seen as a triangular pyramid.

Regular pyramids | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Digonal | Triangular | Square | Pentagonal | Hexagonal | Heptagonal | Octagonal | Enneagonal | Decagonal... |

| Improper | Regular | Equilateral | Isosceles | |||||

|  |  |  | |||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

A regular tetrahedron can be seen as a degenerate polyhedron, a uniform digonal antiprism, where base polygons are reduced digons.

| Family of uniform antiprisms n.3.3.3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhedron | ||||||||||||

| Tiling | ||||||||||||

Config. | V2.3.3.3 | 3.3.3.3 | 4.3.3.3 | 5.3.3.3 | 6.3.3.3 | 7.3.3.3 | 8.3.3.3 | 9.3.3.3 | 10.3.3.3 | 11.3.3.3 | 12.3.3.3 | ...∞.3.3.3 |

A regular tetrahedron can be seen as a degenerate polyhedron, a uniform dual digonal trapezohedron, containing 6 vertices, in two sets of colinear edges.

| Family of trapezohedra V.n.3.3.3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhedron |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||

| Tiling |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||

Config. | V2.3.3.3 | V3.3.3.3 | V4.3.3.3 | V5.3.3.3 | V6.3.3.3 | V7.3.3.3 | V8.3.3.3 | ...V10.3.3.3 | ...V12.3.3.3 | ...V∞.3.3.3 |

A truncation process applied to the tetrahedron produces a series of uniform polyhedra. Truncating edges down to points produces the octahedron as a rectified tetrahedron. The process completes as a birectification, reducing the original faces down to points, and producing the self-dual tetrahedron once again.

Family of uniform tetrahedral polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Symmetry: [3,3], (*332) | [3,3]+, (332) | ||||||

|  |  |  | ||||

3,3 | t3,3 | r3,3 | t3,3 | 3,3 | rr3,3 | tr3,3 | sr3,3 |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|  |  |  |  | |||

V3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3 | V3.4.3.4 | V4.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 |

This polyhedron is topologically related as a part of sequence of regular polyhedra with Schläfli symbols 3,n, continuing into the hyperbolic plane.

| *n32 symmetry mutation of regular tilings: 3,n | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyper. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

3.3 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 3∞ | 312i | 39i | 36i | 33i |

The tetrahedron is topologically related to a series of regular polyhedra and tilings with order-3 vertex figures.

| *n32 symmetry mutation of regular tilings: n,3 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical | Euclidean | Compact hyperb. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

2,3 | 3,3 | 4,3 | 5,3 | 6,3 | 7,3 | 8,3 | ∞,3 | 12i,3 | 9i,3 | 6i,3 | 3i,3 |

- Compounds of tetrahedra

Two tetrahedra in a cube

Compound of five tetrahedra

Compound of ten tetrahedra

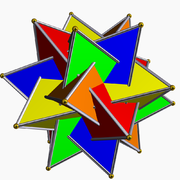

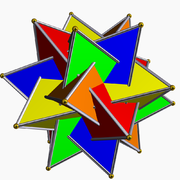

An interesting polyhedron can be constructed from five intersecting tetrahedra. This compound of five tetrahedra has been known for hundreds of years. It comes up regularly in the world of origami. Joining the twenty vertices would form a regular dodecahedron. There are both left-handed and right-handed forms, which are mirror images of each other.

The square hosohedron is another polyhedron with four faces, but it does not have triangular faces.

Applications

Numerical analysis

An irregular volume in space can be approximated by an irregular triangulated surface, and irregular tetrahedral volume elements.

In numerical analysis, complicated three-dimensional shapes are commonly broken down into, or approximated by, a polygonal mesh of irregular tetrahedra in the process of setting up the equations for finite element analysis especially in the numerical solution of partial differential equations. These methods have wide applications in practical applications in computational fluid dynamics, aerodynamics, electromagnetic fields, civil engineering, chemical engineering, naval architecture and engineering, and related fields.

Chemistry

The ammonium ion is tetrahedral

The tetrahedron shape is seen in nature in covalently bonded molecules. All sp3-hybridized atoms are surrounded by atoms (or lone electron pairs) at the four corners of a tetrahedron. For instance in a methane molecule (CH

4) or an ammonium ion (NH+

4), four hydrogen atoms surround a central carbon or nitrogen atom with tetrahedral symmetry. For this reason, one of the leading journals in organic chemistry is called Tetrahedron. The central angle between any two vertices of a perfect tetrahedron is arccos(−1/3), or approximately 109.47°.[6][26]

Water, H

2O, also has a tetrahedral structure, with two hydrogen atoms and two lone pairs of electrons around the central oxygen atoms. Its tetrahedral symmetry is not perfect, however, because the lone pairs repel more than the single O–H bonds.

Quaternary phase diagrams in chemistry are represented graphically as tetrahedra.

However, quaternary phase diagrams in communication engineering are represented graphically on a two-dimensional plane.

Electricity and electronics

If six equal resistors are soldered together to form a tetrahedron, then the resistance measured between any two vertices is half that of one resistor.[27][28]

Since silicon is the most common semiconductor used in solid-state electronics, and silicon has a valence of four, the tetrahedral shape of the four chemical bonds in silicon is a strong influence on how crystals of silicon form and what shapes they assume.

Games

4-sided die

The Royal Game of Ur, dating from 2600 BC, was played with a set of tetrahedral dice.

Especially in roleplaying, this solid is known as a 4-sided die, one of the more common polyhedral dice, with the number rolled appearing around the bottom or on the top vertex. Some Rubik's Cube-like puzzles are tetrahedral, such as the Pyraminx and Pyramorphix.

Color space

Tetrahedra are used in color space conversion algorithms specifically for cases in which the luminance axis diagonally segments the color space (e.g. RGB, CMY).[29]

Contemporary art

The Austrian artist Martina Schettina created a tetrahedron using fluorescent lamps. It was shown at the light art biennale Austria 2010.[30]

It is used as album artwork, surrounded by black flames on The End of All Things to Come by Mudvayne.

Popular culture

Stanley Kubrick originally intended the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey to be a tetrahedron, according to Marvin Minsky, a cognitive scientist and expert on artificial intelligence who advised Kubrick on the HAL 9000 computer and other aspects of the movie. Kubrick scrapped the idea of using the tetrahedron as a visitor who saw footage of it did not recognize what it was and he did not want anything in the movie regular people did not understand.[31]

In Season 6, Episode 15 of Futurama, named "Möbius Dick", the Planet Express crew pass through an area in space known as the Bermuda Tetrahedron. Many other ships passing through the area have mysteriously disappeared, including that of the first Planet Express crew.

In the 2013 film Oblivion the large structure in orbit above the Earth is of a tetrahedron design and referred to as the Tet.

Geology

The tetrahedral hypothesis, originally published by William Lowthian Green to explain the formation of the Earth,[32] was popular through the early 20th century.[33][34]

Structural engineering

A tetrahedron having stiff edges is inherently rigid. For this reason it is often used to stiffen frame structures such as spaceframes.

Aviation

At some airfields, a large frame in the shape of a tetrahedron with two sides covered with a thin material is mounted on a rotating pivot and always points into the wind. It is built big enough to be seen from the air and is sometimes illuminated. Its purpose is to serve as a reference to pilots indicating wind direction.[35]

Tetrahedral graph

| Tetrahedral graph | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vertices | 4 |

| Edges | 6 |

| Radius | 1 |

| Diameter | 1 |

| Girth | 3 |

| Automorphisms | 24 |

| Chromatic number | 4 |

| Properties | Hamiltonian, regular, symmetric, distance-regular, distance-transitive, 3-vertex-connected, planar graph |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

The skeleton of the tetrahedron (the vertices and edges) form a graph, with 4 vertices, and 6 edges. It is a special case of the complete graph, K4, and wheel graph, W4.[36] It is one of 5 Platonic graphs, each a skeleton of its Platonic solid.

3-fold symmetry |

See also

- Boerdijk–Coxeter helix

- Caltrop

Demihypercube and simplex – n-dimensional analogues- Hill tetrahedron

Pentachoron – 4-dimensional analogue- Schläfli orthoscheme

- Tetra Pak

- Tetrahedral kite

- Tetrahedral number

- Tetrahedron packing

Triangular dipyramid – constructed by joining two tetrahedra along one face- Trirectangular tetrahedron

- Synergetics

References

^ ab Weisstein, Eric W. "Tetrahedron". MathWorld..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Ford, Walter Burton; Ammerman, Charles (1913), Plane and Solid Geometry, Macmillan, pp. 294–295

^ abcdef Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald; Regular Polytopes, Methuen and Co., 1948, Table I(i)

^ Köller, Jürgen, "Tetrahedron", Mathematische Basteleien, 2001

^ "Angle Between 2 Legs of a Tetrahedron", Maze5.net

^ ab Brittin, W. E. (1945). "Valence angle of the tetrahedral carbon atom". Journal of Chemical Education. 22 (3): 145. Bibcode:1945JChEd..22..145B. doi:10.1021/ed022p145.

^ Park, Poo-Sung. "Regular polytope distances", Forum Geometricorum 16, 2016, 227-232. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2016volume16/FG201627.pdf

^ Sections of a Tetrahedron

^ "Simplex Volumes and the Cayley-Menger Determinant", MathPages.com

^ Kahan, William M.; "What has the Volume of a Tetrahedron to do with Computer Programming Languages?", pp.11

^ Kahan, William M.; "What has the Volume of a Tetrahedron to do with Computer Programming Languages?", pp. 16–17

^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Tetrahedron." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Tetrahedron.html

^ Altshiller-Court, N. "The tetrahedron." Ch. 4 in Modern Pure Solid Geometry: Chelsea, 1979.

^ Murakami, Jun; Yano, Masakazu (2005), "On the volume of a hyperbolic and spherical tetrahedron", Communications in Analysis and Geometry, 13 (2): 379–400, doi:10.4310/cag.2005.v13.n2.a5, ISSN 1019-8385, MR 2154824, archived from the original on 10 April 2012, retrieved 10 February 2012

^ Havlicek, Hans; Weiß, Gunter (2003). "Altitudes of a tetrahedron and traceless quadratic forms" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly. 110 (8): 679–693. arXiv:1304.0179. doi:10.2307/3647851. JSTOR 3647851.

^ Leung, Kam-tim; and Suen, Suk-nam; "Vectors, matrices and geometry", Hong Kong University Press, 1994, pp. 53–54

^ Outudee, Somluck; New, Stephen. The Various Kinds of Centres of Simplices (PDF). Dept of Mathematics, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Audet, Daniel (May 2011). "Déterminants sphérique et hyperbolique de Cayley-Menger" (PDF). Bulletin AMQ.

^ Senechal, Marjorie (1981). "Which tetrahedra fill space?". Mathematics Magazine. Mathematical Association of America. 54 (5): 227–243. doi:10.2307/2689983. JSTOR 2689983

^ Rassat, André; Fowler, Patrick W. (2004). "Is There a "Most Chiral Tetrahedron"?". Chemistry: A European Journal. 10 (24): 6575–6580. doi:10.1002/chem.200400869

^ Lee, Jung Rye (June 1997). "The Law of Cosines in a Tetrahedron". J. Korea Soc. Math. Educ. Ser. B: Pure Appl. Math.

^ abcd Inequalities proposed in “Crux Mathematicorum”, [1].

^ Crelle, A. L. (1821). "Einige Bemerkungen über die dreiseitige Pyramide". Sammlung mathematischer Aufsätze u. Bemerkungen 1 (in German). Berlin: Maurer. pp. 105–132. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

^ Todhunter, I. (1886), Spherical Trigonometry: For the Use of Colleges and Schools, p. 129 ( Art. 163 )

^ ab Wacław Sierpiński, Pythagorean Triangles, Dover Publications, 2003 (orig. ed. 1962).

^ "Angle Between 2 Legs of a Tetrahedron" – Maze5.net

^ Klein, Douglas J. (2002). "Resistance-Distance Sum Rules" (PDF). Croatica Chemica Acta. 75 (2): 633–649. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

^ Záležák, Tomáš (18 October 2007); "Resistance of a regular tetrahedron" (PDF), retrieved 25 Jan 2011

^ Vondran, Gary L. (April 1998). "Radial and Pruned Tetrahedral Interpolation Techniques" (PDF). HP Technical Report. HPL-98-95: 1–32.

^ Lightart-Biennale Austria 2010

^ "Marvin Minsky: Stanley Kubrick Scraps the Tetrahedron". Web of Stories. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

^ Green, William Lowthian (1875). Vestiges of the Molten Globe, as exhibited in the figure of the earth, volcanic action and physiography. Part I. London: E. Stanford. OCLC 3571917.

^ Holmes, Arthur (1965). Principles of physical geology. Nelson. p. 32.

^ Hitchcock, Charles Henry (January 1900). Winchell, Newton Horace, ed. "William Lowthian Green and his Theory of the Evolution of the Earth's Features". The American Geologist. XXV. Geological Publishing Company. pp. 1–10.

^ Federal Aviation Administration (2009), Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, U. S. Government Printing Office, p. 13-10, ISBN 9780160876110.

^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Tetrahedral graph". MathWorld.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tetrahedron. |

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Tetrahedron". MathWorld.

- Free paper models of a tetrahedron and many other polyhedra

An Amazing, Space Filling, Non-regular Tetrahedron that also includes a description of a "rotating ring of tetrahedra", also known as a kaleidocycle.

Fundamental convex regular and uniform polytopes in dimensions 2–10 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Family | An | Bn | I2(p) / Dn | E6 / E7 / E8 / F4 / G2 | Hn | |||||||

Regular polygon | Triangle | Square | p-gon | Hexagon | Pentagon | |||||||

Uniform polyhedron | Tetrahedron | Octahedron • Cube | Demicube | Dodecahedron • Icosahedron | ||||||||

Uniform 4-polytope | 5-cell | 16-cell • Tesseract | Demitesseract | 24-cell | 120-cell • 600-cell | |||||||

Uniform 5-polytope | 5-simplex | 5-orthoplex • 5-cube | 5-demicube | |||||||||

Uniform 6-polytope | 6-simplex | 6-orthoplex • 6-cube | 6-demicube | 122 • 221 | ||||||||

Uniform 7-polytope | 7-simplex | 7-orthoplex • 7-cube | 7-demicube | 132 • 231 • 321 | ||||||||

Uniform 8-polytope | 8-simplex | 8-orthoplex • 8-cube | 8-demicube | 142 • 241 • 421 | ||||||||

Uniform 9-polytope | 9-simplex | 9-orthoplex • 9-cube | 9-demicube | |||||||||

Uniform 10-polytope | 10-simplex | 10-orthoplex • 10-cube | 10-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform n-polytope | n-simplex | n-orthoplex • n-cube | n-demicube | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 | n-pentagonal polytope | |||||||

| Topics: Polytope families • Regular polytope • List of regular polytopes and compounds | ||||||||||||