Function (mathematics)

| Function | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x ↦ f (x) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Examples by domain and codomain | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classes/properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Constant · Identity · Linear · Polynomial · Rational · Algebraic · Analytic · Smooth · Continuous · Measurable · Injective · Surjective · Bijective | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Constructions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Restriction · Composition · λ · Inverse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Generalizations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Partial · Multivalued · Implicit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In mathematics, a function[1] was originally the idealization of how a varying quantity depends on another quantity. For example, the position of a planet is a function of time. Historically, the concept was elaborated with the infinitesimal calculus at the end of the 17th century, and, until the 19th century, the functions that were considered were differentiable (that is, they had a high degree of regularity). The concept of function was formalized at the end of the 19th century in terms of set theory, and this greatly enlarged the domains of application of the concept.

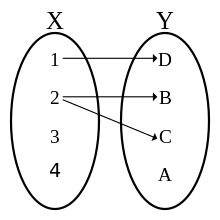

A function is a process or a relation that associates each element x of a set X, the domain of the function, to a single element y of another set Y (possibly the same set), the codomain of the function. If the function is called f, this relation is denoted y = f (x) (read f of x), the element x is the argument or input of the function, and y is the value of the function, the output, or the image of x by f.[2] The symbol that is used for representing the input is the variable of the function (one often says that f is a function of the variable x).

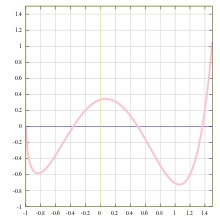

A function is uniquely represented by its graph which is the set of all pairs (x, f (x)). When the domain and the codomain are sets of numbers, each such pair may be considered as the Cartesian coordinates of a point in the plane. In general, these points form a curve, which is also called the graph of the function. This is a useful representation of the function, which is commonly used everywhere. For example, graphs of functions are commonly used in newspapers for representing the evolution of price indexes and stock market indexes

Functions are widely used in science, and in most fields of mathematics. Their role is so important that it has been said that they are "the central objects of investigation" in most fields of mathematics.[3]

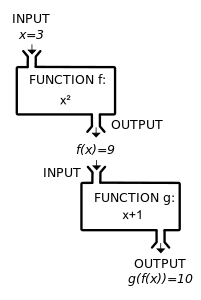

Schematic depiction of a function described metaphorically as a "machine" or "black box" that for each input yields a corresponding output

The red curve is the graph of a function, because any vertical line has exactly one crossing point with the curve.

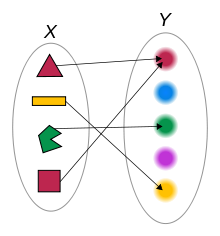

A function that associates any of the four colored shapes to its color.

Contents

1 Definition

1.1 Relational approach

1.2 As an element of a Cartesian product over a domain

2 Notation

2.1 Functional notation

2.2 Arrow notation

2.3 Index notation

2.4 Dot notation

2.5 Specialized notations

3 Map vs function

4 Specifying a function

5 Representing a function

5.1 Graphs and plots

5.2 Tables

5.3 Bar chart

6 General properties

6.1 Canonical functions

6.2 Function composition

6.3 Image and preimage

6.4 Injective, surjective and bijective functions

6.5 Restriction and extension

7 Multivariate function

8 In calculus

8.1 Real function

8.2 Function of several real or complex variables

8.3 Vector-valued function

9 Function space

10 Multi-valued functions

11 In foundations of mathematics and set theory

12 In computer science

13 See also

13.1 Subpages

13.2 Generalizations

13.3 Related topics

14 Notes

15 References

16 Further reading

17 External links

Definition

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Intuitively, a function is a process that associates to each element of a set X a single element of a set Y.

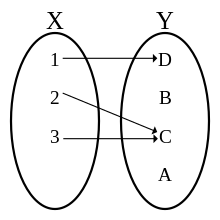

Formally, a function f from a set X to a set Y is defined by a set G of ordered pairs (x, y) such that x ∈ X, y ∈ Y, and every element of X is the first component of exactly one ordered pair in G.[4][note 1] In other words, for every x in X, there is exactly one element y such that the ordered pair (x, y) belongs to the set of pairs defining the function f. The set G is called the graph of the function. Formally speaking, it may be identified with the function, but this hides the usual interpretation of a function as a process. Therefore, in common usage, the function is generally distinguished from its graph. Functions are also called maps or mappings, though some authors make some distinction between "maps" and "functions" (see #Map vs function).

In the definition of function, X and Y are respectively called the domain and the codomain of the function f. If (x, y) belongs to the set defining f, then y is the image of x under f, or the value of f applied to the argument x. Especially in the context of numbers, one says also that y is the value of f for the value x of its variable, or, still shorter, y is the value of f of x, denoted as y = f(x).

Two functions f and g are equal if their domain and codomain sets are the same and their output values agree on the whole domain. Formally, f = g if f(x) = g(x) for all x ∈ X, where f:X → Y and g:X → Y.[5][6][note 2]

The domain and codomain are not always explicitly given when a function is defined, and, without some (possibly difficult) computation, one knows only that the domain is contained in a larger set. Typically, this occurs in mathematical analysis, where "a function from X to Y " often refers to a function that may have a proper subset of X as domain. For example, a "function from the reals to the reals" may refer to a real-valued function of a real variable, and this phrase does not mean that the domain of the function is the whole set of the real numbers, but only that the domain is a set of real numbers that contains a non-empty open interval; such a function is then called a partial function. For example, if f is a function that has the real numbers as domain and codomain, then a function mapping the value x to the value g(x)=1f(x)displaystyle g(x)=tfrac 1f(x)

The range of a function is the set of the images of all elements in the domain. However, range is sometimes used as a synonym of codomain, generally in old textbooks.

Relational approach

Any subset of the Cartesian product of a domain Xdisplaystyle X

A univalent relation is a relation such that

- (x,y)∈R∧(x,z)∈R⇒y=z.displaystyle (x,y)in R;land ;(x,z)in Rquad Rightarrow quad y=z.

Univalent relations may be identified to functions whose domain is a subset of X.

A left-total relation is a relation such that

- ∀x∈X∃y∈Y:(x,y)∈R.displaystyle forall xin X;exists yin Ycolon (x,y)in R.

Formally, functions may be identified to relations that are both univalent and left total. Violating the left-totality is similar to giving a convenient encompassing set instead of the true domain, as explained above.

Various properties of functions and function composition may be reformulated in the language of relations. For example, a function is injective if the converse relation RT⊆(Y×X)displaystyle R^textTsubseteq (Ytimes X)

As an element of a Cartesian product over a domain

A function is sometimes identified with an element of Cartesian products over the domain of the function. Namely, given sets X,Ydisplaystyle X,Y

- ∏XYdisplaystyle prod _XY

over the index set Xdisplaystyle X

Note: infinite Cartesian products are often simply "defined" as sets of functions.[8]

Notation

There are various standard ways for denoting functions. The most commonly used notation is functional notation, which defines the function using an equation that gives the names of the function and the argument explicitly. This gives rise to a subtle point, often glossed over in elementary treatments of functions: functions are distinct from their values. Thus, a function f should be distinguished from its value f(x0) at the value x0 in its domain. To some extent, even working mathematicians will conflate the two in informal settings for convenience, and to avoid the use of pedantic language. However, strictly speaking, it is an abuse of notation to write "let f:R→Rdisplaystyle fcolon mathbb R to mathbb R

This distinction in language and notation becomes important in cases where functions themselves serve as inputs for other functions. (A function taking another function as an input is termed a functional.) Other approaches to denoting functions, detailed below, avoid this problem but are less commonly used.

Functional notation

As first used by Leonhard Euler in 1734,[9] functions are denoted by a symbol consisting generally of a single letter in italic font, most often the lower-case letters f, g, h. Some widely used functions are represented by a symbol consisting of several letters (usually two or three, generally an abbreviation of their name). By convention, in this case, a roman type is used, such as "sin" for the sine function, in contrast to italic font for single-letter symbols.

The notation (read: "y equals f of x")

- y=f(x)displaystyle y=f(x)

means that the pair (x, y) belongs to the set of pairs defining the function f. If X is the domain of f, the set of pairs defining the function is thus, using set-builder notation,

- (x,f(x)):x∈X.displaystyle (x,f(x)):xin X.

Often, a definition of the function is given by what f does to the explicit argument x. For example, a function f can be defined by the equation

- f(x)=sin(x2+1)displaystyle f(x)=sin(x^2+1)

for all real numbers x. In this example, f can be thought of as the composite of several simpler functions: squaring, adding 1, and taking the sine. However, only the sine function has a common explicit symbol (sin), while the combination of squaring and then adding 1 is described by the polynomial expression x2+1displaystyle x^2+1

Sometimes the parentheses of functional notation are omitted when the symbol denoting the function consists of several characters and no ambiguity may arise. For example, sinxdisplaystyle sin x

Arrow notation

For explicitly expressing domain X and the codomain Y of a function f, the arrow notation is often used (read: "the function f from X to Y" or "the function f mapping elements of X to elements of Y"):

- f:X→Ydisplaystyle fcolon Xto Y

or

- X →f Y.displaystyle X~stackrel fto ~Y.

This is often used in relation with the arrow notation for elements (read: "f maps x to f (x)"), often stacked immediately below the arrow notation giving the function symbol, domain, and codomain:

- x↦f(x).displaystyle xmapsto f(x).

For example, if a multiplication is defined on a set X, then the square function sqrdisplaystyle operatorname sqr

- sqr:X→Xx↦x⋅x,displaystyle beginalignedoperatorname sqr colon X&to X\x&mapsto xcdot x,endaligned

the latter line being more commonly written

- x↦x2.displaystyle xmapsto x^2.

Often, the expression giving the function symbol, domain and codomain is omitted. Thus, the arrow notation is useful for avoiding introducing a symbol for a function that is defined, as it is often the case, by a formula expressing the value of the function in terms of its argument. As a common application of the arrow notation, suppose f:X×X→Y;(x,t)↦f(x,t)displaystyle fcolon Xtimes Xto Y;;(x,t)mapsto f(x,t)

Index notation

Index notation is often used instead of functional notation. That is, instead of writing f (x), one writes fx.displaystyle f_x.

This is typically the case for functions whose domain is the set of the natural numbers. Such a function is called a sequence, and, in this case the element fndisplaystyle f_n

The index notation is also often used for distinguishing some variables called parameters from the "true variables". In fact, parameters are specific variables that are considered as being fixed during the study of a problem. For example, the map x↦f(x,t)displaystyle xmapsto f(x,t)

Dot notation

In the notation

x↦f(x),displaystyle xmapsto f(x),

the symbol x does not represent any value, it is simply a placeholder meaning that, if x is replaced by any value on the left of the arrow, it should be replaced by the same value on the right of the arrow. Therefore, x may be replaced by any symbol, often an interpunct " ⋅ ". This may be useful for distinguishing the function f (⋅) from its value f (x) at x.

For example, a(⋅)2displaystyle a(cdot )^2

Specialized notations

There are other, specialized notations for functions in sub-disciplines of mathematics. For example, in linear algebra and functional analysis, linear forms and the vectors they act upon are denoted using a dual pair to show the underlying duality. This is similar to the use of bra–ket notation in quantum mechanics. In logic and the theory of computation, the function notation of lambda calculus is used to explicitly express the basic notions of function abstraction and application. In category theory and homological algebra, networks of functions are described in terms of how they and their compositions commute with each other using commutative diagrams that extend and generalize the arrow notation for functions described above.

Map vs function

A function is often also called a map or a mapping. But some authors make a distinction between the term "map" and "function". For example, the term "map" is often reserved for a "function" with some sort of special structure; e.g., a group homomorphism between groups can simply be called a map between those groups for the sake of succinctness. See also: maps of manifolds. Some authors[10] reserve the word mapping to the case where the codomain Y belongs explicitly to the definition of the function. In this sense, the graph of the mapping recovers the function as the set of pairs.

Because the term "map" is synonymous with "morphism" in category theory, the term "map" can in particular emphasize the aspect that a function is a morphism in the category of sets: in the informal definition of function f:X→Ydisplaystyle f:Xto Y

Some authors, such as Serge Lang,[11] use "function" only to refer to maps in which the codomain is a set of numbers (i.e. a subset of the fields R or C) and the term mapping for more general functions.

In the theory of dynamical systems, a map denotes an evolution function used to create discrete dynamical systems. See also Poincaré map.

A partial map is a partial function, and a total map is a total function. Related terms like domain, codomain, injective, continuous, etc. can be applied equally to maps and functions, with the same meaning. All these usages can be applied to "maps" as general functions or as functions with special properties.

Specifying a function

Given a function fdisplaystyle f

- On a finite set, a function may be defined by listing the elements of the codomain that are associated to the elements of the domain. E.g., if A=1,2,3displaystyle A=1,2,3

, then one can define a function f:A→Rdisplaystyle f:Ato mathbb R

by f(1)=2,f(2)=3,f(3)=4.displaystyle f(1)=2,f(2)=3,f(3)=4.

- Depending on a function, if possible, one might use a (closed) formula to define the function. For example, in the above example, fdisplaystyle f

can be defined by the formula f(n)=n+1displaystyle f(n)=n+1

, for n∈1,2,3displaystyle nin 1,2,3

.

- One often combines arithmetic or algebraic operations to define a new function; for example, a function f:R→Rdisplaystyle f:mathbb R to mathbb R

, defined by f(x)=1+x2displaystyle f(x)=sqrt 1+x^2

, is defined by a combination of the polynomial 1+x2displaystyle 1+x^2

and the square root function.

- The following is an example of an implicit definition of a function: using calculus, one can show that, for each real number xdisplaystyle x

, y2=x2+1displaystyle y^2=x^2+1

has two distinct real roots, a positive and a negative one. One can then define f:R→Rdisplaystyle f:mathbb R to mathbb R

by saying that f(x)displaystyle f(x)

is the positive root of the equation y2=x2+1displaystyle y^2=x^2+1

(cf. #Multi-valued functions). This is the same function as the previous one. The natural logarithm is often defined by an appeal to the implicit function theorem.

- A power series can be used to define a function on the domain in which the series converges: for example, the exponential function is given by ex=∑n=0∞xnn!displaystyle e^x=sum _n=0^infty x^n over n!

.

- In general, given a function fdisplaystyle f

, there might not be a (closed) formula or condition that can be used to define it. An elementary function[note 3] is a function that can be defined by a finite number of applications of arithmetic operations and composition involving only constants, arithmetic operations, exponential functions, logarithms, and roots of polynomials.

- A choice function in the axiom of choice is an example of a function that exists only by postulation.

A recurrence relation is sometimes used to define a function. That this can be done relies formally on the following theorem.

Recursion theorem[12] — Let φ:X→Xdisplaystyle varphi :Xto X

The theorem is a consequence of the axiom of induction of the natural numbers in the Peano axioms (there is also a transfinite version of the above theorem; see transfinite recursion.) Another inductive way of specifying a function is through analytic continuation. For example, for a complex variable sdisplaystyle s

- ∑n=1∞1nsdisplaystyle sum _n=1^infty frac 1n^s

can be shown to converge if the real part of sdisplaystyle s

Differential equations are sometimes used to define a function. For example, the natural logarithm is the solution of the initial value problem d(ln|x|)dx=1xdisplaystyle frac )dx=frac 1x

Representing a function

A graph is commonly used to give an intuitive picture of a function. As an example of how a graph helps understand a function, it is easy to see from its graph whether a function is increasing or decreasing. Some functions may also be represented by bar charts.

Graphs and plots

The function mapping each year to its US motor vehicle death count, shown as a line chart

The same function, shown as a bar chart

Given a function f:X→Y,displaystyle fcolon Xto Y,

- G=(x,f(x)):x∈X.displaystyle G=(x,f(x)):xin X.

In the frequent case where X and Y are subsets of the real numbers (or may be identified with such subsets, e.g. intervals), an element (x,y)∈Gdisplaystyle (x,y)in G

- x↦x2,displaystyle xmapsto x^2,

consisting of all points with coordinates (x,x2)displaystyle (x,x^2)

Tables

A function can be represented as a table of values. If the domain of a function is finite, then the function can be completely specified in this way. For example, the multiplication function f:1,…,52→Rdisplaystyle fcolon 1,ldots ,5^2to mathbb R

y x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

On the other hand, if a function's domain is continuous, a table can give the values of the function at specific values of the domain. If an intermediate value is needed, interpolation can be used to estimate the value of the function. For example, a portion of a table for the sine function might be given as follows, with values rounded to 6 decimal places:

| x | sin x |

|---|---|

| 1.289 | 0.960557 |

| 1.290 | 0.960835 |

| 1.291 | 0.961112 |

| 1.292 | 0.961387 |

| 1.293 | 0.961662 |

Before the advent of handheld calculators and personal computers, such tables were often compiled and published for functions such as logarithms and trigonometric functions.

Bar chart

Bar charts are often used for representing functions whose domain is a finite set, the natural numbers, or the integers. In this case, an element x of the domain is represented by an interval of the x-axis, and the corresponding value of the function, f(x), is represented by a rectangle whose base is the interval corresponding to x and whose height is f(x) (possibly negative, in which case the bar extends below the x-axis).

General properties

This section describes general properties of functions, that are independent of specific properties of the domain and the codomain.

Canonical functions

Some functions are uniquely defined by their domain and codomain, and are sometimes called canonical:

- For every set X, there is a unique function, called the empty function from the empty set to X. This function is not interesting by itself, but useful for simplifying statements, similarly as the empty sum (equal to 0) and the empty product equal to 1.

- For every set X and every singleton set s, there is a unique function, called the canonical surjection, from X to s, which maps to s every element of X. This is a surjection (see below), except if X is the empty set.

- Given a function f:X→Y,displaystyle fcolon Xto Y,

the canonical surjection of f onto its image f(X)=f(x)∣x∈Xdisplaystyle f(X)=f(x)mid xin X

is the function from X to f(X) that maps x to f(x)

- For every subset X of a set Y, the canonical injection of X into Y is the injective (see below) function that maps every element of X to itself.

- The identity function of X, often denoted by idXdisplaystyle operatorname id _X

is the canonical injection of X into itself.

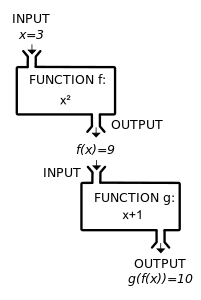

Function composition

Given two functions f:X→Ydisplaystyle fcolon Xto Y

- (g∘f)(x)=g(f(x)).displaystyle (gcirc f)(x)=g(f(x)).

That is, the value of g∘fdisplaystyle gcirc f

The composition g∘fdisplaystyle gcirc f

The function composition is associative in the sense that, if one of (h∘g)∘fdisplaystyle (hcirc g)circ f

- h∘g∘f=(h∘g)∘f=h∘(g∘f).displaystyle hcirc gcirc f=(hcirc g)circ f=hcirc (gcirc f).

The identity functions idXdisplaystyle operatorname id _X

f∘idX=idY∘f=f.displaystyle fcirc operatorname id _X=operatorname id _Ycirc f=f.

A composite function g(f(x)) can be visualized as the combination of two "machines".

A simple example of a function composition

Another composition. In this example, (g ∘ f )(c) = #.

Image and preimage

Let f:X→Y.displaystyle fcolon Xto Y.

- f(A)=f(x)∣x∈A.displaystyle f(A)=f(x)mid xin A.

The image of f is the image of the whole domain, that is f(X). It is also called the range of f, although the term may also refer to the codomain.[13]

On the other hand, the inverse image, or preimage by f of a subset B of the codomain Y is the subset of the domain X consisting of all elements of X whose images belong to B. It is denoted by f−1(B).displaystyle f^-1(B).

- f−1(B)=x∈X∣f(x)∈B.displaystyle f^-1(B)=xin Xmid f(x)in B.

For example, the preimage of 4, 9 under the square function is the set −3,−2,2,3.

By definition of a function, the image of an element x of the domain is always a single element of the codomain. However, the preimage of a single element y, denoted f−1(x),displaystyle f^-1(x),

If f:X→Ydisplaystyle fcolon Xto Y

- A⊆B⟹f(A)⊆f(B)displaystyle Asubseteq BLongrightarrow f(A)subseteq f(B)

- C⊆D⟹f−1(C)⊆f−1(D)displaystyle Csubseteq DLongrightarrow f^-1(C)subseteq f^-1(D)

- A⊆f−1(f(A))displaystyle Asubseteq f^-1(f(A))

- C⊇f(f−1(C))displaystyle Csupseteq f(f^-1(C))

- f(f−1(f(A)))=f(A)displaystyle f(f^-1(f(A)))=f(A)

- f−1(f(f−1(C)))=f−1(C)displaystyle f^-1(f(f^-1(C)))=f^-1(C)

The preimage by f of an element y of the codomain is sometimes called, in some contexts, the fiber of y under f.

If a function f has an inverse (see below), this inverse is denoted f−1.displaystyle f^-1.

![displaystyle f[A],f^-1[C]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d728b72b3681c1a33529ac867bc49952dc812a4)

Injective, surjective and bijective functions

Let f:X→Ydisplaystyle fcolon Xto Y

The function f is injective (or one-to-one, or is an injection) if f(a) ≠ f(b) for any two different elements a and b of X. Equivalently, f is injective if, for any y∈Y,displaystyle yin Y,

The function f is surjective (or onto, or is a surjection) if the range equals the codomain, that is, if f(X) = Y. In other words, the preimage f−1(y)displaystyle f^-1(y)

The function f is bijective (or is bijection or a one-to-one correspondence) if it is both injective and surjective. That is f is bijective if, for any y∈Y,displaystyle yin Y,

Every function f:X→Ydisplaystyle fcolon Xto Y

"One-to-one" and "onto" are terms that were more common in the older English language literature; "injective", "surjective", and "bijective" were originally coined as French words in the second quarter of the 20th century by the Bourbaki group and imported into English. As a word of caution, "a one-to-one function" is one that is injective, while a "one-to-one correspondence" refers to a bijective function. Also, the statement "f maps X onto Y" differs from "f maps X into B" in that the former implies that f is surjective), while the latter makes no assertion about the nature of f the mapping. In a complicated reasoning, the one letter difference can easily be missed. Due to the confusing nature of this older terminology, these terms have declined in popularity relative to the Bourbakian terms, which have also the advantage to be more symmetrical.

Restriction and extension

If f:X→Ydisplaystyle fcolon Xto Y

- f|S(x)=f(x)for all x∈S.displaystyle f_S(x)=f(x)quad textfor all xin S.

This often used for define partial inverse functions: if there is a subset S of a function f such that f|S is injective, then the canonical surjection of f|S on its image f|S(S) = f(S) is a bijection, which has an inverse function from f(S) to S. This is in this way that inverse trigonometric functions are defined. The cosine function, for example, is injective, when restricted to the interval (–0, π); the image of this restriction is the interval (–1, 1); this defines thus an inverse function from (–1, 1) to (–0, π), which is called arccosine and denoted arccos.

Function restriction may also be used for "gluing" functions together: let X=⋃i∈IUidisplaystyle textstyle X=bigcup _iin IU_i

An extension of a function f is a function g such that f is a restriction of g. A typical use of this concept is the process of analytic continuation, that allows extending functions whose domain is a small part of the complex plane to functions whose domain is almost the whole complex plane.

Here is another classical example of a function extension that is encountered when studying homographies of the real line. An homography is a function h(x)=ax+bcx+ddisplaystyle h(x)=frac ax+bcx+d

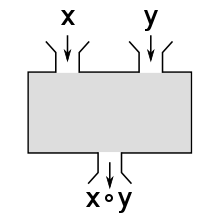

Multivariate function

A binary operation is a typical example of a bivariate, function which assigns to each pair (x,y)displaystyle (x,y)

the result x∘ydisplaystyle xcirc y

the result x∘ydisplaystyle xcirc y .

.A multivariate function, or function of several variables is a function that depends on several arguments. Such functions are commonly encountered. For example, the position of a car on a road is a function of the time and its speed.

More formally, a function of n variables is a function whose domain is a set of n-tuples.

For example, multiplication of integers is a function of two variables, or bivariate function, whose domain is the set of all pairs (2-tuples) of integers, and whose codomain is the set of integers. The same is true for every binary operation. More generally, every mathematical operation is defined as a multivariate function.

The Cartesian product X1×⋯×Xndisplaystyle X_1times cdots times X_n

- f:U→Y,displaystyle fcolon Uto Y,

where the domain U has the form

- U⊆X1×⋯×Xn.displaystyle Usubseteq X_1times cdots times X_n.

When using function notation, one usually omits the parentheses surrounding tuples, writing f(x1,x2)displaystyle f(x_1,x_2)

In the case where all the Xidisplaystyle X_i

It is common to also consider functions whose codomain is a product of sets. For example, Euclidean division maps every pair (a, b) of integers with b ≠ 0 to a pair of integers called the quotient and the remainder:

- Euclidean division:Z×(Z∖0)→Z×Z(a,b)↦(quotient(a,b),remainder(a,b)).displaystyle beginalignedtextEuclidean divisioncolon quad mathbb Z times (mathbb Z setminus 0)&to mathbb Z times mathbb Z \(a,b)&mapsto (operatorname quotient (a,b),operatorname remainder (a,b)).endaligned

The codomain may also be a vector space. In this case, one talks of a vector-valued function. If the domain is contained in a Euclidean space, or more generally a manifold, a vector-valued function is often called a vector field.

In calculus

The idea of function, starting in the 17th century, was fundamental to the new infinitesimal calculus (see History of the function concept). At that time, only real-valued functions of a real variable were considered, and all functions were assumed to be smooth. But the definition was soon extended to functions of several variables and to function of a complex variable. In the second half of the 19th century, the mathematically rigorous definition of a function was introduced, and functions with arbitrary domains and codomains were defined.

Functions are now used throughout all areas of mathematics. In introductory calculus, when the word function is used without qualification, it means a real-valued function of a single real variable. The more general definition of a function is usually introduced to second or third year college students with STEM majors, and in their senior year they are introduced to calculus in a larger, more rigorous setting in courses such as real analysis and complex analysis.

Real function

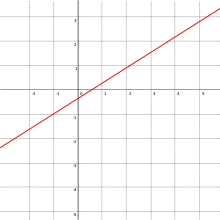

Graph of a linear function

Graph of a polynomial function, here a quadratic function.

Graph of two trigonometric functions: sine and cosine.

A real function is a real-valued function of a real variable, that is, a function whose codomain is the field of real numbers and whose domain is a set of real numbers that contains an interval. In this section, these functions are simply called functions.

The functions that are most commonly considered in mathematics and its applications have some regularity, that is they are continuous, differentiable, and even analytic. This regularity insures that these functions can be visualized by their graphs. In this section, all functions are differentiable in some interval.

Functions enjoy pointwise operations, that is, if f and g are functions, their sum, difference and product are functions defined by

- (f+g)(x)=f(x)+g(x)(f−g)(x)=f(x)−g(x)(f⋅g)(x)=f(x)⋅g(x).displaystyle beginaligned(f+g)(x)&=f(x)+g(x)\(f-g)(x)&=f(x)-g(x)\(fcdot g)(x)&=f(x)cdot g(x)\endaligned.

The domains of the resulting functions are the intersection of the domains of f and g. The quotient of two functions is defined similarly by

- fg(x)=f(x)g(x),displaystyle frac fg(x)=frac f(x)g(x),

but the domain of the resulting function is obtained by removing the zeros of g from the intersection of the domains of f and g.

The polynomial functions are defined by polynomials, and their domain is the whole set of real numbers. They include constant functions, linear functions and quadratic functions. Rational functions are quotients of two polynomial functions, and their domain is the real numbers with a finite number of them removed to avoid division by zero. The simplest rational function is the function x↦1x,displaystyle xmapsto frac 1x,

The derivative of a real differentiable function is a real function. An antiderivative of a continuous real function is a real function that is differentiable in any open interval in which the original function is continuous. For example, the function x↦1xdisplaystyle xmapsto frac 1x

A real function f is monotonic in an interval if the sign of f(x)−f(y)x−ydisplaystyle frac f(x)-f(y)x-y

Many other real functions are defined either by the implicit function theorem (the inverse function is a particular instance) or as solutions of differential equations. For example, the sine and the cosine functions are the solutions of the linear differential equation

- y″+y=0displaystyle y''+y=0

such that

- sin0=0,cos0=1,∂sinx∂x(0)=1,∂cosx∂x(0)=0.displaystyle sin 0=0,quad cos 0=1,quad frac partial sin xpartial x(0)=1,quad frac partial cos xpartial x(0)=0.

Function of several real or complex variables

Functions of several real (or complex) variables are functions which domain consists of tuples of real (or complex) numbers. This is, the domain is a subset of Rndisplaystyle mathbb R ^n

In the case of functions of several variables, the functional notation can be used in two ways. The symbol f(x)displaystyle f(x)

Vector-valued function

When the elements of the co-domain of a function are vectors the function is said to be a vector-valued function. These functions are particularly useful in applications, for example modeling physical properties. The function that associates to each point of a fluid its velocity vector is a vector-valued function.

Some vector-valued function are defined on a subset of Rndisplaystyle mathbb R ^n

Function space

In mathematical analysis, and more specifically in functional analysis, a function space is a set of scalar-valued or vector-valued functions, which share a specific property and form a topological vector space. For example, the real smooth functions with a compact support (that is, they are zero outside some compact set) form a function space that is at the basis of the theory of distributions.

Function spaces play a fundamental role in advanced mathematical analysis, by allowing the use of their algebraic and topological properties for studying properties of functions. For example, all theorems of existence and uniqueness of solutions of ordinary or partial differential equations result of the study of function spaces.

Multi-valued functions

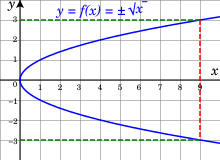

Together, the two square roots of all nonnegative real numbers form a single smooth curve.

Several methods for specifying functions of real or complex variables start from a local definition of the function at a point or on a neighbourhood of a point, and then extend by continuity the function to a much larger domain. Frequently, for a starting point x0,displaystyle x_0,

For example, in defining the square root as the inverse function of the square function, for any positive real number x0,displaystyle x_0,

In the preceding example, one choice, the positive square root, is more natural than the other. This is not the case in general. For example, let consider the implicit function that maps y to a root x of x3−3x−y=0displaystyle x^3-3x-y=0

Usefulness of the concept of multi-valued functions is clearer when considering complex functions, typically analytic functions. The domain to which a complex function may be extended by analytic continuation generally consists of almost the whole complex plane. However, when extending the domain through two different paths, one often gets different values. For example, when extending the domain of the square root function, along a path of complex numbers with positive imaginary parts, one gets i for the square root of –1; while, when extending through complex numbers with negative imaginary parts, one gets –i. There are generally two ways of solving the problem. One may define a function that is not continuous along some curve, called a branch cut. Such a function is called the principal value of the function. The other way is to consider that one has a multi-valued function, which is analytic everywhere except for isolated singularities, but whose value may "jump" if one follows a closed loop around a singularity. This jump is called the monodromy.

In foundations of mathematics and set theory

The definition of a function that is given in this article requires the concept of set, since the domain and the codomain of a function must be a set. This is not a problem in usual mathematics, as it is generally not difficult to consider only functions whose domain and codomain are sets, which are well defined, even if the domain is not explicitly defined. However, it is sometimes useful to consider more general functions.

For example, the singleton set may be considered as a function x↦x.displaystyle xmapsto x.

These generalized functions may be critical in the development of a formalization of foundations of mathematics. For example, the Von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel set theory, is an extension of the set theory in which the collection of all sets is a class. This theory includes the replacement axiom, which may be interpreted as "if X is a set, and F is a function, then F[X] is a set".

In computer science

In computer science, functions are callable units of code. For example, the code

define square_function(x):

return x*x

can be called by the expression square_function(x), where x can be replaced, for example, by numeric literals as in square_function(2) or identifiers of other valid input.

The calling of the unit of code consists in the expression square_function(x) being replaced by the execution of the code inside the function's definition. In the example, it would be replaced by executing the evaluation of the expression x*x. This expression in turn, could be indicating to compute the multiplication of x by itself, in the case of x representing a numeric value. The evaluation would then compute the square of x. The result of this evaluation is called the return value of the function.

As in the example, some functions in computer science behave like mathematical functions. The computer science function of the example would normally behave for numerical inputs like the mathematical function f(x)=x2displaystyle f(x)=x^2

A function may[clarification needed] be described by an algorithm, and any kind of algorithm may[clarification needed] be used. Sometimes, the definition of a function may involve elements or properties that can be defined, but not computed. For example, if one considers the set Pdisplaystyle mathcal P

The above ways of defining functions define them "pointwise", that is, each value is defined independently of the other values. This is not necessarily the case.

See also

Subpages

- List of types of functions

- List of functions

- Function fitting

- Implicit function

Generalizations

- Homomorphism

- Morphism

- Distribution

- Functor

Related topics

- Associative array

- Functional

- Functional decomposition

- Functional predicate

- Functional programming

- Parametric equation

- Elementary function

- Closed-form expression

Notes

^ The sets X, Y are parts of data defining a function; i.e., a function is a set of ordered pairs (x,y)displaystyle (x,y)with x∈X,y∈Ydisplaystyle xin X,yin Y

, together with the sets X, Y, such that for each x∈Xdisplaystyle xin X

, there is a unique y∈Ydisplaystyle yin Y

with (x,y)displaystyle (x,y)

in the set.

^ This follows from the axiom of extensionality, which says two sets are the same if and only if they have the same members. Some authors drop codomain from a definition of a function, and in that definition, the notion of equality has to be handled with care; see, for example, https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1403122/when-do-two-functions-become-equal

^ Here "elementary" has not exactly its common sense: although most functions that are encountered in elementary courses of mathematics are elementary in this sense, some elementary functions are not elementary for the common sense, for example, those that involve roots of polynomials of high degree.

^ The words map, mapping, transformation, correspondence, and operator are often used synonymously. Halmos 1970, p. 30.

^ MacLane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1967). Algebra (First ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 1–13..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Spivak 2008, p. 39.

^ Hamilton, A. G. (1982). Numbers, sets, and axioms: the apparatus of mathematics. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-521-24509-8.

^ Apostol 1981, p. 35.

^ Kaplan 1972, p. 25.

^ Gunther Schmidt( 2011) Relational Mathematics, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 132, sect 5.1 Functions, pp. 49–60, Cambridge University Press

ISBN 978-0-521-76268-7 CUP blurb for Relational Mathematics

^ Halmos, Naive Set Theory, 1968, sect.9 ("Families")

^ Ron Larson, Bruce H. Edwards (2010), Calculus of a Single Variable, Cengage Learning, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-538-73552-0

^ T. M. Apostol (1981). Mathematical Analysis. Addison-Wesley. p. 35.

^ Lang, Serge (1971), Linear Algebra (2nd ed.), Addison-Wesley, p. 83

^ Jacobson, § 0.4. pg 16.

^ Quantities and Units - Part 2: Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural sciences and technology, p. 15. ISO 80000-2 (ISO/IEC 2009-12-01)

^ Gödel 1940, p. 16; Jech 2003, p. 11; Cunningham 2016, p. 57

References

Bartle, Robert (1967). The Elements of Real Analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Bloch, Ethan D. (2011). Proofs and Fundamentals: A First Course in Abstract Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-7126-5.

Cunningham, Daniel W. (2016). Set theory: A First Course. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-12032-7.

Gödel, Kurt (1940). The Consistency of the Continuum Hypothesis. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07927-1.

Halmos, Paul R. (1970). Naive Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90092-6.

Jech, Thomas (2003). Set theory (Third Millennium ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-44085-7.

Spivak, Michael (2008). Calculus (4th ed.). Publish or Perish. ISBN 978-0-914098-91-1.

Further reading

Anton, Howard (1980). Calculus with Analytical Geometry. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-03248-9.

Bartle, Robert G. (1976). The Elements of Real Analysis (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-05464-1.

Dubinsky, Ed; Harel, Guershon (1992). The Concept of Function: Aspects of Epistemology and Pedagogy. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-081-7.

Hammack, Richard (2009). "12. Functions" (PDF). Book of Proof. Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

Husch, Lawrence S. (2001). Visual Calculus. University of Tennessee. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

Katz, Robert (1964). Axiomatic Analysis. D. C. Heath and Company.

Kleiner, Israel (1989). "Evolution of the Function Concept: A Brief Survey". The College Mathematics Journal. 20 (4): 282–300. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.113.6352. doi:10.2307/2686848. JSTOR 2686848.

Lützen, Jesper (2003). "Between rigor and applications: Developments in the concept of function in mathematical analysis". In Porter, Roy. The Cambridge History of Science: The modern physical and mathematical sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57199-9. An approachable and diverting historical presentation.

Malik, M. A. (1980). "Historical and pedagogical aspects of the definition of function". International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 11 (4): 489–492. doi:10.1080/0020739800110404.- Reichenbach, Hans (1947) Elements of Symbolic Logic, Dover Publishing Inc., New York,

ISBN 0-486-24004-5.

Ruthing, D. (1984). "Some definitions of the concept of function from Bernoulli, Joh. to Bourbaki, N.". Mathematical Intelligencer. 6 (4): 72–77.

Thomas, George B.; Finney, Ross L. (1995). Calculus and Analytic Geometry (9th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-53174-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Functions (mathematics). |

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4- Weisstein, Eric W. "Function". MathWorld.

The Wolfram Functions Site gives formulae and visualizations of many mathematical functions.- NIST Digital Library of Mathematical Functions