Centroid

Centroid of a triangle

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (April 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics and physics, the centroid or geometric center of a plane figure is the arithmetic mean position of all the points in the figure. Informally, it is the point at which a cutout of the shape could be perfectly balanced on the tip of a pin.[1]

The definition extends to any object in n-dimensional space: its centroid is the mean position of all the points in all of the coordinate directions.[2]

While in geometry the word barycenter is a synonym for centroid, in astrophysics and astronomy, the barycenter is the center of mass of two or more bodies that orbit each other. In physics, the center of mass is the arithmetic mean of all points weighted by the local density or specific weight. If a physical object has uniform density, its center of mass is the same as the centroid of its shape.

In geography, the centroid of a radial projection of a region of the Earth's surface to sea level is the region's geographical center.

Contents

1 History

2 Properties

3 Examples

4 Locating

4.1 Plumb line method

4.2 Balancing method

4.3 Of a finite set of points

4.4 By geometric decomposition

4.5 By integral formula

4.5.1 Bounded region

4.6 Of an L-shaped object

4.7 Of a triangle

4.8 Of a polygon

4.9 Of a cone or pyramid

4.10 Of a tetrahedron and n-dimensional simplex

4.11 Of a hemisphere

5 See also

6 Notes

7 References

8 External links

History

The term "centroid" is of recent coinage (1814). It is used as a substitute for the older terms "center of gravity," and "center of mass", when the purely geometrical aspects of that point are to be emphasized. The term is peculiar to the English language. The French use "centre de gravité" on most occasions, and others use terms of similar meaning.

The center of gravity, as the name indicates, is a notion that arose in mechanics, most likely in connection with building activities. When, where, and by whom it was invented is not known, as it is a concept that likely occurred to many people individually with minor differences.

While it is possible Euclid was still active in Alexandria during the childhood of Archimedes (287-212 BCE), it is certain that when Archimedes visited Alexandria, Euclid was no longer there. Thus Archimedes could not have learned the theorem that the medians of a triangle meet in a point—the center of gravity of the triangle directly from Euclid, as this proposition is not in Euclid's Elements. The first explicit statement of this proposition is due to Heron of Alexandria (perhaps the first century CE) and occurs in his Mechanics. It may be added, in passing, that the proposition did not become common in the textbooks on plane geometry until the nineteenth century.

While Archimedes does not state that proposition explicitly, he makes indirect references to it, suggesting he was familiar with it. However, Jean Etienne Montucla (1725-1799), the author of the first history of mathematics (1758), declares categorically (vol. I, p. 463) that the center of gravity of solids is a subject Archimedes did not touch.

In 1802 Charles Bossut (1730-1813) published a two-volume Essai aur PhisMire generale des mathematiques. This book was highly esteemed by his contemporaries, judging from the fact that within two years after its publication it was already available in translation in Italian (1802-03), English (1803), and German (1804). Bossut credits Archimedes with having found the centroid of plane figures, but has nothing to say about solids.[3]

Properties

The geometric centroid of a convex object always lies in the object. A non-convex object might have a centroid that is outside the figure itself. The centroid of a ring or a bowl, for example, lies in the object's central void.

If the centroid is defined, it is a fixed point of all isometries in its symmetry group. In particular, the geometric centroid of an object lies in the intersection of all its hyperplanes of symmetry. The centroid of many figures (regular polygon, regular polyhedron, cylinder, rectangle, rhombus, circle, sphere, ellipse, ellipsoid, superellipse, superellipsoid, etc.) can be determined by this principle alone.

In particular, the centroid of a parallelogram is the meeting point of its two diagonals. This is not true for other quadrilaterals.

For the same reason, the centroid of an object with translational symmetry is undefined (or lies outside the enclosing space), because a translation has no fixed point.

Examples

The centroid of a triangle is the intersection of the three medians of the triangle (each median connecting a vertex with the midpoint of the opposite side).[4]

For other properties of a triangle's centroid, see below.

Locating

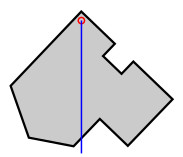

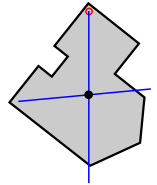

Plumb line method

The centroid of a uniformly dense planar lamina, such as in figure (a) below, may be determined experimentally by using a plumbline and a pin to find the collocated center of mass of a thin body of uniform density having the same shape. The body is held by the pin, inserted at a point, off the presumed centroid in such a way that it can freely rotate around the pin; the plumb line is then dropped from the pin (figure b). The position of the plumbline is traced on the surface, and the procedure is repeated with the pin inserted at any different point (or a number of points) off the centroid of the object. The unique intersection point of these lines will be the centroid (figure c). Provided that the body is of uniform density, all lines made this way will include the centroid, and all lines will cross at the exact same place.

|  |  |

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

This method can be extended (in theory) to concave shapes where the centroid may lie outside the shape, and virtually to solids (again, of uniform density), where the centroid may lie within the body. The (virtual) positions of the plumb lines need to be recorded by means other than by drawing them along the shape.

Balancing method

For convex two-dimensional shapes, the centroid can be found by balancing the shape on a smaller shape, such as the top of a narrow cylinder. The centroid occurs somewhere within the range of contact between the two shapes (and exactly at the point where the shape would balance on a pin). In principle, progressively narrower cylinders can be used to find the centroid to arbitrary precision. In practice air currents make this infeasible. However, by marking the overlap range from multiple balances, one can achieve a considerable level of accuracy.

Of a finite set of points

The centroid of a finite set of kdisplaystyle k

C=x1+x2+⋯+xkkdisplaystyle mathbf C =frac mathbf x _1+mathbf x _2+cdots +mathbf x _kk.[5]

This point minimizes the sum of squared Euclidean distances between itself and each point in the set.

By geometric decomposition

The centroid of a plane figure Xdisplaystyle X

- Cx=∑CixAi∑Ai,Cy=∑CiyAi∑Aidisplaystyle C_x=frac sum C_i_xA_isum A_i,C_y=frac sum C_i_yA_isum A_i

Holes in the figure Xdisplaystyle X

For example, the figure below (a) is easily divided into a square and a triangle, both with positive area; and a circular hole, with negative area (b).

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

The centroid of each part can be found in any list of centroids of simple shapes (c). Then the centroid of the figure is the weighted average of the three points. The horizontal position of the centroid, from the left edge of the figure is

- x=5×102+13.33×12102−3×π2.52102+12102−π2.52≈8.5 units.displaystyle x=frac 5times 10^2+13.33times frac 1210^2-3times pi 2.5^210^2+frac 1210^2-pi 2.5^2approx 8.5mbox units.

The vertical position of the centroid is found in the same way.

The same formula holds for any three-dimensional objects, except that each Aidisplaystyle A_i

By integral formula

The centroid of a subset X of Rndisplaystyle mathbb R ^n

- C=∫xg(x)dx∫g(x)dxdisplaystyle C=frac int xg(x);dxint g(x);dx

where the integrals are taken over the whole space Rndisplaystyle mathbb R ^n

Another formula for the centroid is

- Ck=∫zSk(z)dz∫Sk(z)dzdisplaystyle C_k=frac int zS_k(z);dzint S_k(z);dz

where Ck is the kth coordinate of C, and Sk(z) is the measure of the intersection of X with the hyperplane defined by the equation xk = z. Again, the denominator is simply the measure of X.

For a plane figure, in particular, the barycenter coordinates are

- Cx=∫xSy(x)dxAdisplaystyle C_mathrm x =frac int xS_mathrm y (x);dxA

- Cy=∫ySx(y)dyAdisplaystyle C_mathrm y =frac int yS_mathrm x (y);dyA

where A is the area of the figure X; Sy(x) is the length of the intersection of X with the vertical line at abscissa x; and Sx(y) is the analogous quantity for the swapped axes.

Bounded region

The centroid (x¯,y¯)displaystyle (bar x,;bar y)

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

x¯=1A∫abx[f(x)−g(x)]dxdisplaystyle bar x=frac 1Aint _a^bx[f(x)-g(x)];dx[7]

y¯=1A∫ab[f(x)+g(x)2][f(x)−g(x)]dx,displaystyle bar y=frac 1Aint _a^bleft[frac f(x)+g(x)2right][f(x)-g(x)];dx,[8]

where Adisplaystyle A

![int _a^b[f(x)-g(x)];dx](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/330a8d134eb2862c942f79455c2e150ee835f0ff)

Of an L-shaped object

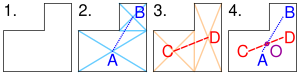

This is a method of determining the centroid of an L-shaped object.

- Divide the shape into two rectangles, as shown in fig 2. Find the centroids of these two rectangles by drawing the diagonals. Draw a line joining the centroids. The centroid of the shape must lie on this line AB.

- Divide the shape into two other rectangles, as shown in fig 3. Find the centroids of these two rectangles by drawing the diagonals. Draw a line joining the centroids. The centroid of the L-shape must lie on this line CD.

- As the centroid of the shape must lie along AB and also along CD, it must be at the intersection of these two lines, at O. The point O might not lie inside the L-shaped object.

Of a triangle

|

The centroid of a triangle is the point of intersection of its medians (the lines joining each vertex with the midpoint of the opposite side).[11] The centroid divides each of the medians in the ratio 2:1, which is to say it is located ⅓ of the distance from each side to the opposite vertex (see figures at right).[12][13] Its Cartesian coordinates are the means of the coordinates of the three vertices. That is, if the three vertices are L=(xL,yL),displaystyle L=(x_L,y_L),

- C=13(L+M+N)=(13(xL+xM+xN),13(yL+yM+yN)).displaystyle C=frac 13(L+M+N)=left(frac 13(x_L+x_M+x_N),;;frac 13(y_L+y_M+y_N)right).

The centroid is therefore at 13:13:13displaystyle tfrac 13:tfrac 13:tfrac 13

In trilinear coordinates the centroid can be expressed in any of these equivalent ways in terms of the side lengths a, b, c and vertex angles L, M, N:[14]

C=1a:1b:1c=bc:ca:ab=cscL:cscM:cscNdisplaystyle C=frac 1a:frac 1b:frac 1c=bc:ca:ab=csc L:csc M:csc N- =cosL+cosM⋅cosN:cosM+cosN⋅cosL:cosN+cosL⋅cosMdisplaystyle =cos L+cos Mcdot cos N:cos M+cos Ncdot cos L:cos N+cos Lcdot cos M

- =secL+secM⋅secN:secM+secN⋅secL:secN+secL⋅secM.displaystyle =sec L+sec Mcdot sec N:sec M+sec Ncdot sec L:sec N+sec Lcdot sec M.

- =cosL+cosM⋅cosN:cosM+cosN⋅cosL:cosN+cosL⋅cosMdisplaystyle =cos L+cos Mcdot cos N:cos M+cos Ncdot cos L:cos N+cos Lcdot cos M

The centroid is also the physical center of mass if the triangle is made from a uniform sheet of material; or if all the mass is concentrated at the three vertices, and evenly divided among them. On the other hand, if the mass is distributed along the triangle's perimeter, with uniform linear density, then the center of mass lies at the Spieker center (the incenter of the medial triangle), which does not (in general) coincide with the geometric centroid of the full triangle.

The area of the triangle is 1.5 times the length of any side times the perpendicular distance from the side to the centroid.[15]

A triangle's centroid lies on its Euler line between its orthocenter H and its circumcenter O, exactly twice as close to the latter as to the former:

CH¯=2CO¯.displaystyle overline CH=2overline CO.[16][17]

In addition, for the incenter I and nine-point center N, we have

- CH¯=4CN¯CO¯=2CN¯IC¯<HC¯IH¯<HC¯IC¯<IO¯displaystyle beginalignedoverline CH&=4overline CN\overline CO&=2overline CN\overline IC&<overline HC\overline IH&<overline HC\overline IC&<overline IOendaligned

If G is the centroid of the triangle ABC, then:

- (Area of △ABG)=(Area of △ACG)=(Area of △BCG)=13(Area of △ABC)displaystyle displaystyle (textArea of triangle mathrm ABG )=(textArea of triangle mathrm ACG )=(textArea of triangle mathrm BCG )=frac 13(textArea of triangle mathrm ABC )

The isogonal conjugate of a triangle's centroid is its symmedian point.

Any of the three medians through the centroid divides the triangle's area in half. This is not true for other lines through the centroid; the greatest departure from the equal-area division occurs when a line through the centroid is parallel to a side of the triangle, creating a smaller triangle and a trapezoid; in this case the trapezoid's area is 5/9 that of the original triangle.[18]

Let P be any point in the plane of a triangle with vertices A, B, and C and centroid G. Then the sum of the squared distances of P from the three vertices exceeds the sum of the squared distances of the centroid G from the vertices by three times the squared distance between P and G:

PA2+PB2+PC2=GA2+GB2+GC2+3PG2.displaystyle PA^2+PB^2+PC^2=GA^2+GB^2+GC^2+3PG^2.[19]

The sum of the squares of the triangle's sides equals three times the sum of the squared distances of the centroid from the vertices:

AB2+BC2+CA2=3(GA2+GB2+GC2).displaystyle AB^2+BC^2+CA^2=3(GA^2+GB^2+GC^2).[20]

A triangle's centroid is the point that maximizes the product of the directed distances of a point from the triangle's sidelines.[21]

Let ABC be a triangle, let G be its centroid, and let D, E, and F be the midpoints of BC, CA, and AB, respectively. For any point P in the plane of ABC then

PA+PB+PC≤2(PD+PE+PF)+3PG.displaystyle PA+PB+PCleq 2(PD+PE+PF)+3PG.[22]

Of a polygon

The centroid of a non-self-intersecting closed polygon defined by n vertices (x0,y0), (x1,y1), ..., (xn−1,yn−1) is the point (Cx, Cy),[23] where

Cx=16A∑i=0n−1(xi+xi+1)(xi yi+1−xi+1 yi)displaystyle C_mathrm x =frac 16Asum _i=0^n-1(x_i+x_i+1)(x_i y_i+1-x_i+1 y_i), and

Cy=16A∑i=0n−1(yi+yi+1)(xi yi+1−xi+1 yi)displaystyle C_mathrm y =frac 16Asum _i=0^n-1(y_i+y_i+1)(x_i y_i+1-x_i+1 y_i),

and where A is the polygon's signed area,[23] as described by

A=12∑i=0n−1(xi yi+1−xi+1 yi)displaystyle A=frac 12sum _i=0^n-1(x_i y_i+1-x_i+1 y_i);.

In these formulas, the vertices are assumed to be numbered in order of their occurrence along the polygon's perimeter; furthermore, the vertex ( xn, yn ) is assumed to be the same as ( x0, y0 ), meaning i+1displaystyle i+1

Of a cone or pyramid

The centroid of a cone or pyramid is located on the line segment that connects the apex to the centroid of the base. For a solid cone or pyramid, the centroid is 1/4 the distance from the base to the apex. For a cone or pyramid that is just a shell (hollow) with no base, the centroid is 1/3 the distance from the base plane to the apex.

Of a tetrahedron and n-dimensional simplex

A tetrahedron is an object in three-dimensional space having four triangles as its faces. A line segment joining a vertex of a tetrahedron with the centroid of the opposite face is called a median, and a line segment joining the midpoints of two opposite edges is called a bimedian. Hence there are four medians and three bimedians. These seven line segments all meet at the centroid of the tetrahedron.[24] The medians are divided by the centroid in the ratio 3:1. The centroid of a tetrahedron is the midpoint between its Monge point and circumcenter (center of the circumscribed sphere). These three points define the Euler line of the tetrahedron that is analogous to the Euler line of a triangle.

These results generalize to any n-dimensional simplex in the following way. If the set of vertices of a simplex is v0,…,vndisplaystyle v_0,ldots ,v_n

- C=1n+1∑i=0nvi.displaystyle C=frac 1n+1sum _i=0^nv_i.

The geometric centroid coincides with the center of mass if the mass is uniformly distributed over the whole simplex, or concentrated at the vertices as n equal masses.

Of a hemisphere

The centroid of a solid hemisphere (i.e. half of a solid ball) divides the line segment connecting the sphere's center to the hemisphere's pole in the ratio 3:8. The centroid of a hollow hemisphere (i.e. half of a hollow sphere) divides the line segment connecting the sphere's center to the hemisphere's pole in half.

See also

- Chebyshev center

- Fréchet mean

- K-means algorithm

- List of centroids

- Pappus's centroid theorem

- Triangle center

- Locating the center of mass

- Spectral centroid

- Medoid

Notes

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 521)

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 520)

^ Court, Nathan Altshiller (1960). "Notes on the centroid". The Mathematics Teacher. 53 (1): 33–35..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 66)

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 520)

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 526)

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 526)

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 527)

^ Protter & Morrey, Jr. (1970, p. 528)

^ Larson (1998, pp. 458–460)

^ Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 66)

^ Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 65)

^ Kay (1969, p. 184)

^ Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangles "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2012-06-02.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Johnson (2007, p. 173)

^ Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 101)

^ Kay (1969, pp. 18,189,225–226)

^ Bottomley, Henry. "Medians and Area Bisectors of a Triangle". Retrieved 27 September 2013.

^ Altshiller-Court (1925, pp. 70–71)

^ Altshiller-Court (1925, pp. 70–71)

^ Clark Kimberling, "Trilinear distance inequalities for the symmedian point, the centroid, and other triangle centers", Forum Geometricorum, 10 (2010), 135--139. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2010volume10/FG201015index.html

^ Gerald A. Edgar, Daniel H. Ullman & Douglas B. West (2018) Problems and Solutions, The American Mathematical Monthly, 125:1, 81-89, DOI: 10.1080/00029890.2018.1397465

^ ab Bourke (1997)

^ Leung, Kam-tim; and Suen, Suk-nam; "Vectors, matrices and geometry", Hong Kong University Press, 1994, pp. 53–54

References

Altshiller-Court, Nathan (1925), College Geometry: An Introduction to the Modern Geometry of the Triangle and the Circle (2nd ed.), New York: Barnes & Noble, LCCN 52013504

Bourke, Paul (July 1997). "Calculating the area and centroid of a polygon".

Johnson, Roger A. (2007), Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover

Kay, David C. (1969), College Geometry, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, LCCN 69012075

Larson, Roland E.; Hostetler, Robert P.; Edwards, Bruce H. (1998), Calculus of a Single Variable (6th ed.), Houghton Mifflin Company

Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Jr., Charles B. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, LCCN 76087042

External links

Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers by Clark Kimberling. The centroid is indexed as X(2).

Characteristic Property of Centroid at cut-the-knot

Barycentric Coordinates at cut-the-knot- Interactive animations showing Centroid of a triangle and Centroid construction with compass and straightedge

Experimentally finding the medians and centroid of a triangle at Dynamic Geometry Sketches, an interactive dynamic geometry sketch using the gravity simulator of Cinderella.