Planck constant

| Value of h (2018) | Units | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 6966662607015000000♠6.62607015×10−34 | J⋅s | [1][2][3][4] |

| Values of h (2014) | Units | Ref. |

| 6966662607015000000♠6.626070150(81)×10−34 | J⋅s | [5] |

| 6985413566766200000♠4.135667662(25)×10−15 | eV⋅s | [6] |

| 2π | EP⋅tP | |

| Values of ħ (h-bar) | Units | Ref. |

| 6966105457179999999♠1.054571800(13)×10−34 | J⋅s | [6] |

| 6984658211951400000♠6.582119514(40)×10−16 | eV⋅s | [6] |

| 1 | EP⋅tP | |

| Values of hc | Units | Ref. |

| 6975198644568000000♠1.98644568×10−25 | J⋅m | |

| 7000123984193000000♠1.23984193 | eV⋅μm | |

| 2π | EP⋅ℓP | |

| Values of ħc (h-bar) | Units | Ref. |

| 6974316152649000000♠3.16152649×10−26 | J⋅m | |

| 6999197326970000000♠0.19732697 | eV⋅μm | |

| 1 | EP⋅ℓP |

Plaque at the Humboldt University of Berlin: "Max Planck, discoverer of the elementary quantum of action h, taught in this building from 1889 to 1928."

The Planck constant (denoted h, also called Planck's constant) is a physical constant that is the quantum of action, which relates the energy carried by a photon to its frequency. A photon's energy is equal to its frequency multiplied by the Planck constant. The Planck constant is of fundamental importance in quantum mechanics, and in physical measurement, it is the basis for the definition of the kilogram.

At the end of the 19th-century, physicists were unable to explain why the observed spectrum of black body radiation, which by then had been accurately measured, diverged significantly at higher frequencies from that predicted by existing theories. In 1900, Max Planck empirically derived a formula for the observed spectrum by assuming that a hypothetical electrically charged oscillator in a cavity that contained black body radiation could only change its energy in a minimal increment, E, that was proportional to the frequency of its associated electromagnetic wave. He was able to calculate the proportionality constant, h, from the experimental measurements, and that constant is named in his honor. In 1905, the value E was associated by Albert Einstein with a "quantum" or minimal element of the energy of the electromagnetic wave itself. The light quantum behaved in some respects as an electrically neutral particle, as opposed to an electromagnetic wave. It was eventually called a photon.

Since energy and mass are equivalent, the Planck constant also relates mass to frequency. By 2017, the Planck constant had been measured with sufficient accuracy in terms of the SI base units, that it was central to replacing the metal cylinder, called the International Prototype of the Kilogram (IPK), that had defined the kilogram since 1889.[7] The kilogram was the last base unit in the SI to be defined by a procedure to relate it to a fundamental physical property. The new definition was unanimously approved at the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) on 16 November 2018 as part of the 2019 redefinition of SI base units.[8] For this new definition of the kilogram, the Planck constant, as defined by the ISO standard, was set to 6966662607015000000♠6.626070150×10−34 J⋅s exactly.[9][10][11]

Contents

1 Significance of the value

2 Origins

2.1 Black-body radiation

2.2 Photoelectric effect

2.3 Atomic structure

2.4 Uncertainty principle

3 Photon energy

4 Value

5 Dependent physical constants

5.1 Rest mass of the electron

5.2 Avogadro constant

5.3 Elementary charge

5.4 Bohr magneton and nuclear magneton

6 Determination

6.1 Josephson constant

6.2 Kibble balance

6.3 Magnetic resonance

6.4 Faraday constant

6.5 X-ray crystal density

6.6 Particle accelerator

7 Fixation

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

11 External links

11.1 Videos

Significance of the value

The Planck constant is related to the quantization of light and matter. It can be seen as a subatomic-scale constant. In a unit system adapted to subatomic scales, the electronvolt is the appropriate unit of energy and the petahertz the appropriate unit of frequency. Atomic unit systems are based (in part) on the Planck constant.

The Planck constant is one of the smallest constants used in physics. This reflects the fact that on a scale adapted to humans, where energies are typically of the order of kilojoules and times are typically of the order of seconds or minutes, the Planck constant (the quantum of action) is very small.

Equivalently, the smallness of the Planck constant reflects the fact that everyday objects and systems are made of a large number of particles. For example, green light with a wavelength of 555 nanometres (a wavelength that can be perceived by the human eye to be green) has a frequency of 7014540000000000000♠540 THz (7014540000000000000♠540×1012 Hz). Each photon has an energy E = hf = 6981358000000000000♠3.58×10−19 J. That is a very small amount of energy in terms of everyday experience, but everyday experience is not concerned with individual photons any more than with individual atoms or molecules. An amount of light more typical in everyday experience (though much larger than the smallest amount perceivable by the human eye) is the energy of one mole of photons; its energy can be computed by multiplying the photon energy by the Avogadro constant, NA ≈ 7023602214075800000♠6.022140758(62)×1023 mol−1, with the result of 7005216000000000000♠216 kJ/mol, about the food energy in three apples.

Origins

Black-body radiation

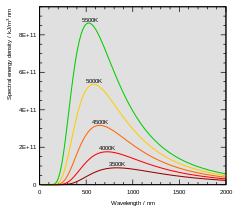

Intensity of light emitted from a black body at any given wavelength. Each curve represents behaviour at a different body temperature. Planck was the first to explain the shape of these curves.

In the last years of the 19th century, Planck was investigating the problem of black-body radiation first posed by Kirchhoff some 40 years earlier. It is well known that hot objects glow, and that hotter objects glow brighter than cooler ones. The electromagnetic field obeys laws of motion similarly to a mass on a spring, and can come to thermal equilibrium with hot atoms. The hot object in equilibrium with light absorbs just as much light as it emits. If the object is black, meaning it absorbs all the light that hits it, then its thermal light emission is maximized.

The assumption that black-body radiation is thermal leads to an accurate prediction: the total amount of emitted energy increases with temperature according to a definite rule, the Stefan–Boltzmann law (1879–84). It was also known that the colour of the light given off by a hot object changes with the temperature, such that "white hot" is hotter than "red hot". Nevertheless, Wilhelm Wien discovered the mathematical relationship between the peaks of the curves at different temperatures, by using the principle of adiabatic invariance. At each different temperature, the curve is moved over by Wien's displacement law (1893). Wien also proposed an approximation for the spectrum of the object, which was correct at high frequencies (short wavelength) but not at low frequencies (long wavelength).[12] It still was not clear why the spectrum of a hot object had the form that it has (see diagram).

Planck hypothesized that the equations of motion for light describe a set of harmonic oscillators, one for each possible frequency. He examined how the entropy of the oscillators varied with the temperature of the body, trying to match Wien's law, and was able to derive an approximate mathematical function for black-body spectrum.[13]

Planck soon realized that his solution was not unique. There were several different solutions, each of which gave a different value for the entropy of the oscillators.[13] To save his theory, Planck resorted to using the then-controversial theory of statistical mechanics,[13] which he described as "an act of despair … I was ready to sacrifice any of my previous convictions about physics."[14] One of his new boundary conditions was

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

to interpret UN [the vibrational energy of N oscillators] not as a continuous, infinitely divisible quantity, but as a discrete quantity composed of an integral number of finite equal parts. Let us call each such part the energy element ε;

— Planck, On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum[13]

With this new condition, Planck had imposed the quantization of the energy of the oscillators, "a purely formal assumption … actually I did not think much about it…" in his own words,[15] but one which would revolutionize physics. Applying this new approach to Wien's displacement law showed that the "energy element" must be proportional to the frequency of the oscillator, the first version of what is now sometimes termed the "Planck–Einstein relation":

- E=hf.displaystyle E=hf.

Planck was able to calculate the value of h from experimental data on black-body radiation: his result, 6966655000000000000♠6.55×10−34 J⋅s, is within 1.2% of the currently accepted value.[13] He also made the first determination of the Boltzmann constant kB from the same data and theory.[16]

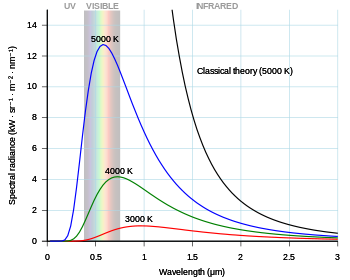

The divergence of the theoretical Rayleigh–Jeans (black) curve from the observed Planck curves at different temperatures.

Prior to Planck's work, it had been assumed that the energy of a body could take on any value whatsoever – that it was a continuous variable. The Rayleigh–Jeans law makes close predictions for a narrow range of values at one limit of temperatures, but the results diverge more and more strongly as temperatures increase. To make Planck's law, which correctly predicts blackbody emissions, it was necessary to multiply the classical expression by a complex factor that involves h in both the numerator and the denominator. The influence of h in this complex factor would not disappear if it were set to zero or to any other value. Making an equation out of Planck's law that would reproduce the Rayleigh–Jeans law could not be done by changing the values of h, of the Boltzmann constant, or of any other constant or variable in the equation. In this case the picture given by classical physics is not duplicated by a range of results in the quantum picture.

The black-body problem was revisited in 1905, when Rayleigh and Jeans (on the one hand) and Einstein (on the other hand) independently proved that classical electromagnetism could never account for the observed spectrum. These proofs are commonly known as the "ultraviolet catastrophe", a name coined by Paul Ehrenfest in 1911. They contributed greatly (along with Einstein's work on the photoelectric effect) in convincing physicists that Planck's postulate of quantized energy levels was more than a mere mathematical formalism. The very first Solvay Conference in 1911 was devoted to "the theory of radiation and quanta".[17] Max Planck received the 1918 Nobel Prize in Physics "in recognition of the services he rendered to the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta".

Photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons (called "photoelectrons") from a surface when light is shone on it. It was first observed by Alexandre Edmond Becquerel in 1839, although credit is usually reserved for Heinrich Hertz,[18] who published the first thorough investigation in 1887. Another particularly thorough investigation was published by Philipp Lenard in 1902.[19] Einstein's 1905 paper[20] discussing the effect in terms of light quanta would earn him the Nobel Prize in 1921,[18] when his predictions had been confirmed by the experimental work of Robert Andrews Millikan.[21] The Nobel committee awarded the prize for his work on the photo-electric effect, rather than relativity, both because of a bias against purely theoretical physics not grounded in discovery or experiment, and dissent amongst its members as to the actual proof that relativity was real.[22][23]

Prior to Einstein's paper, electromagnetic radiation such as visible light was considered to behave as a wave: hence the use of the terms "frequency" and "wavelength" to characterise different types of radiation. The energy transferred by a wave in a given time is called its intensity. The light from a theatre spotlight is more intense than the light from a domestic lightbulb; that is to say that the spotlight gives out more energy per unit time and per unit space (and hence consumes more electricity) than the ordinary bulb, even though the colour of the light might be very similar. Other waves, such as sound or the waves crashing against a seafront, also have their own intensity. However, the energy account of the photoelectric effect didn't seem to agree with the wave description of light.

The "photoelectrons" emitted as a result of the photoelectric effect have a certain kinetic energy, which can be measured. This kinetic energy (for each photoelectron) is independent of the intensity of the light,[19] but depends linearly on the frequency;[21] and if the frequency is too low (corresponding to a photon energy that is less than the work function of the material), no photoelectrons are emitted at all, unless a plurality of photons, whose energetic sum is greater than the energy of the photoelectrons, acts virtually simultaneously (multiphoton effect).[24] Assuming the frequency is high enough to cause the photoelectric effect, a rise in intensity of the light source causes more photoelectrons to be emitted with the same kinetic energy, rather than the same number of photoelectrons to be emitted with higher kinetic energy.[19]

Einstein's explanation for these observations was that light itself is quantized; that the energy of light is not transferred continuously as in a classical wave, but only in small "packets" or quanta. The size of these "packets" of energy, which would later be named photons, was to be the same as Planck's "energy element", giving the modern version of the Planck–Einstein relation:

- E=hf.displaystyle E=hf.

Einstein's postulate was later proven experimentally: the constant of proportionality between the frequency of incident light (f) and the kinetic energy of photoelectrons (E) was shown to be equal to the Planck constant (h).[21]

Atomic structure

A schematization of the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom. The transition shown from the n = 3 level to the n = 2 level gives rise to visible light of wavelength 656 nm (red), as the model predicts.

Niels Bohr introduced the first quantized model of the atom in 1913, in an attempt to overcome a major shortcoming of Rutherford's classical model.[25] In classical electrodynamics, a charge moving in a circle should radiate electromagnetic radiation. If that charge were to be an electron orbiting a nucleus, the radiation would cause it to lose energy and spiral down into the nucleus. Bohr solved this paradox with explicit reference to Planck's work: an electron in a Bohr atom could only have certain defined energies En

- En=−hc0R∞n2,displaystyle E_n=-frac hc_0R_infty n^2,

where c0 is the speed of light in vacuum, R∞ is an experimentally determined constant (the Rydberg constant) and n is any integer (n = 1, 2, 3, …). Once the electron reached the lowest energy level (n = 1), it could not get any closer to the nucleus (lower energy). This approach also allowed Bohr to account for the Rydberg formula, an empirical description of the atomic spectrum of hydrogen, and to account for the value of the Rydberg constant R∞ in terms of other fundamental constants.

Bohr also introduced the quantity h2πdisplaystyle frac h2pi

- J2=j(j+1)ℏ2,j=0,12,1,32,…,Jz=mℏ,m=−j,−j+1,…,j.displaystyle beginalignedJ^2=j(j+1)hbar ^2,qquad &j=0,tfrac 12,1,tfrac 32,ldots ,\J_z=mhbar ,qquad qquad quad &m=-j,-j+1,ldots ,j.endaligned

Uncertainty principle

The Planck constant also occurs in statements of Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. Given a large number of particles prepared in the same state, the uncertainty in their position, Δx, and the uncertainty in their momentum (in the same direction), Δp, obey

- ΔxΔp≥ℏ2,displaystyle Delta x,Delta pgeq frac hbar 2,

where the uncertainty is given as the standard deviation of the measured value from its expected value. There are a number of other such pairs of physically measurable values which obey a similar rule. One example is time vs. energy. The either-or nature of uncertainty forces measurement attempts to choose between trade offs, and given that they are quanta, the trade offs often take the form of either-or (as in Fourier analysis), rather than the compromises and gray areas of time series analysis.

In addition to some assumptions underlying the interpretation of certain values in the quantum mechanical formulation, one of the fundamental cornerstones to the entire theory lies in the commutator relationship between the position operator x^displaystyle hat x

- [p^i,x^j]=−iℏδij,displaystyle [hat p_i,hat x_j]=-ihbar delta _ij,

where δij is the Kronecker delta.

Photon energy

The Planck–Einstein relation connects the particular photon energy E with its associated wave frequency f:

- E=hfdisplaystyle E=hf

This energy is extremely small in terms of ordinarily perceived everyday objects.

Since the frequency f, wavelength λ, and speed of light c are related by f=cλdisplaystyle f=frac clambda

- E=hcλ.displaystyle E=frac hclambda .

The de Broglie wavelength λ of the particle is given by

- λ=hpdisplaystyle lambda =frac hp

where p denotes the linear momentum of a particle, such as a photon, or any other elementary particle.

In applications where it is natural to use the angular frequency (i.e. where the frequency is expressed in terms of radians per second instead of cycles per second or hertz) it is often useful to absorb a factor of 2π into the Planck constant. The resulting constant is called the reduced Planck constant. It is equal to the Planck constant divided by 2π, and is denoted ħ (pronounced "h-bar"):

- ℏ=h2π.displaystyle hbar =frac h2pi .

The energy of a photon with angular frequency ω = 2πf is given by

- E=ℏω,displaystyle E=hbar omega ,

while its linear momentum relates to

- p=ℏk,displaystyle p=hbar k,

where k is an angular wavenumber. In 1923, Louis de Broglie generalized the Planck–Einstein relation by postulating that the Planck constant represents the proportionality between the momentum and the quantum wavelength of not just the photon, but the quantum wavelength of any particle. This was confirmed by experiments soon afterwards. This holds throughout quantum theory, including electrodynamics.

Problems can arise when dealing with frequency or the Planck constant because the units of angular measure (cycle or radian) are omitted in SI.[26][27][28] In the language of quantity calculus,[29] the expression for the "value" of the Planck constant, or of a frequency, is the product of a "numerical value" and a "unit of measurement". When we use the symbol f (or ν) for the value of a frequency it implies the units cycles per second or hertz, but when we use the symbol ω for its value it implies the units radians per second; the numerical values of these two ways of expressing the value of a frequency have a ratio of 2π, but their values are equal. Omitting the units of angular measure "cycle" and "radian" can lead to an error of 2π. A similar state of affairs occurs for the Planck constant. We use the symbol h when we express the value of the Planck constant in J⋅s/cycle, and we use the symbol ħ when we express its value in J⋅s/rad. Since both represent the value of the Planck constant, but in different units, we have h = ħ. Their "values" are equal but, as discussed below, their "numerical values" have a ratio of 2π. In this Wikipedia article the word "value" as used in the tables means "numerical value", and the equations involving the Planck constant and/or frequency actually involve their numerical values using the appropriate implied units. The distinction between "value" and "numerical value" as it applies to frequency and the Planck constant is explained in more detail in this pdf file Link.

These two relations are the temporal and spatial component parts of the special relativistic expression using 4-vectors.

- Pμ=(Ec,p→)=ℏKμ=ℏ(ωc,k→)displaystyle P^mu =left(frac Ec,vec pright)=hbar K^mu =hbar left(frac omega c,vec kright)

Classical statistical mechanics requires the existence of h (but does not define its value).[30] Eventually, following upon Planck's discovery, it was recognized that physical action cannot take on an arbitrary value. Instead, it must be some multiple of a very small quantity, the "quantum of action", now called the Planck constant. This is the so-called "old quantum theory" developed by Bohr and Sommerfeld, in which particle trajectories exist but are hidden, but quantum laws constrain them based on their action. This view has been largely replaced by fully modern quantum theory, in which definite trajectories of motion do not even exist, rather, the particle is represented by a wavefunction spread out in space and in time. Thus there is no value of the action as classically defined. Related to this is the concept of energy quantization which existed in old quantum theory and also exists in altered form in modern quantum physics. Classical physics cannot explain either quantization of energy or the lack of a classical particle motion.

In many cases, such as for monochromatic light or for atoms, quantization of energy also implies that only certain energy levels are allowed, and values in between are forbidden.[31]

Value

The Planck constant has dimensions of physical action; i.e., energy multiplied by time, or momentum multiplied by distance, or angular momentum. In SI units, the Planck constant is expressed in joule-seconds (J⋅s or N⋅m⋅s or kg⋅m2⋅s−1). Implicit in the dimensions of the Planck constant is the fact that the SI unit of frequency, the Hertz, represents one complete cycle, 360 degrees or 2π radians, per second. An angular frequency in radians per second is often more natural in mathematics and physics and many formulas use a reduced Planck constant (or Dirac constant) (pronounced h-bar)

- ℏ=h2πdisplaystyle hbar =h over 2pi

On 16 November 2018, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) voted to redefine the kilogram by fixing the value of the Planck constant, thereby defining the kilogram in terms of the second and the speed of light. Starting 20 May 2019, the new value is exactly

h=6.626 070 15×10−34 J⋅sdisplaystyle h=6.626 070 15times 10^-34 textJcdot texts.

In July 2017, the NIST measured the Planck constant using its Kibble balance instrument with an uncertainty of only 13 parts per billion, obtaining a value of 6966662606993400000♠6.626069934(89)×10−34 J⋅s.[32] This measurement, along with others, allowed the redefinition of SI base units.[33] The two digits inside the parentheses denote the standard uncertainty in the last two digits of the value.

As of the 2014 CODATA release, the best measured value of the Planck constant was:[6]

h=6.626 070 040(81)×10−34 J⋅s=4.135 667 662(25)×10−15 eV⋅sdisplaystyle h=6.626 070 040(81)times 10^-34 textJcdot texts=4.135 667 662(25)times 10^-15 texteVcdot texts.

The value of the reduced Planck constant (or Dirac constant) was:

ℏ=h2π=1.054 571 800(13)×10−34 J⋅s/rad=6.582 119 514(40)×10−16 eV⋅s/raddisplaystyle hbar =h over 2pi =1.054 571 800(13)times 10^-34 textJcdot texts/textrad=6.582 119 514(40)times 10^-16 texteVcdot texts/textrad.

The 2014 CODATA results were made available in June 2015[34] and represent the best-known, internationally accepted values for these constants, based on all data published as of 31 December 2014. New CODATA figures are normally produced every four years. However, in order to support the redefinition of the SI base units, CODATA made a special release that was published in October 2017.[35]

It incorporates all data up to 1 July 2017 and determines the final numerical values of the Planck constant, h, Elementary charge, e, Boltzmann constant, k, and Avogadro constant, NA, that are to be used for the new SI definitions.

Dependent physical constants

There are several related constants for which more than 99% of the uncertainty in the 2014 CODATA values[36] is due to the uncertainty in the value of the Planck constant, as indicated by the square of the correlation coefficient (r2 > 0.99, r > 0.995). The Planck constant is (with one or two exceptions)[37] the fundamental physical constant which is known to the lowest level of precision, with a 1σ relative uncertainty ur of 6992120000000000000♠1.2×10−8.

Rest mass of the electron

The normal textbook derivation of the Rydberg constant R∞ defines it in terms of the electron mass me and a variety of other physical constants.

- R∞=mee48ε02h3c0=mec0α22h.displaystyle R_infty =frac m_rm ee^48varepsilon _0^2h^3c_0=frac m_rm ec_0alpha ^22h.

However, the Rydberg constant can be determined very accurately (ur = 6988590000000000000♠5.9×10−12) from the atomic spectrum of hydrogen, whereas there is no direct method to measure the mass of a stationary electron in SI units. Hence the equation for the computation of me becomes

- me=2R∞hc0α2,displaystyle m_rm e=frac 2R_infty hc_0alpha ^2,

where c0 is the speed of light and α is the fine-structure constant. The speed of light has an exactly defined value in SI units, and the fine-structure constant can be determined more accurately (ur = 6990229999999999999♠2.3×10−10) than the Planck constant. Thus, the uncertainty in the value of the electron rest mass is due entirely to the uncertainty in the value of the Planck constant (r2 > 0.999).

Avogadro constant

The Avogadro constant NA is determined as the ratio of the mass of one mole of electrons to the mass of a single electron; the mass of one mole of electrons is the "relative atomic mass" of an electron Ar(e), which can be measured in a Penning trap (ur = 6989290000000000000♠2.9×10−11), multiplied by the molar mass constant Mu, which is defined as 6997100000000000000♠0.001 M.

- NA=MuAr(e)me=MuAr(e)c0α22R∞h.displaystyle N_rm A=frac M_rm uA_rm r(rm e)m_rm e=frac M_rm uA_rm r(rm e)c_0alpha ^22R_infty h.

The dependence of the Avogadro constant on the Planck constant (r2 > 0.999) also holds for the physical constants which are related to amount of substance, such as the atomic mass constant. The uncertainty in the value of the Planck constant limits the knowledge of the masses of atoms and subatomic particles when expressed in SI units. It is possible to measure the masses more precisely in atomic mass units, but not to convert them more precisely into kilograms.

Elementary charge

Sommerfeld originally defined the fine-structure constant α as:

- α = e2ℏc0 4πε0 = e2c0μ02h,displaystyle alpha = frac e^2hbar c_0 4pi varepsilon _0 = frac e^2c_0mu _02h,

where e is the elementary charge, ε0 is the electric constant (also called the permittivity of free space), and μ0 is the magnetic constant (also called the permeability of free space). The latter two constants have fixed values in the International System of Units. However, α can also be determined experimentally, notably by measuring the electron spin g-factor ge, then comparing the result with the value predicted by quantum electrodynamics.

At present, the most precise value for the elementary charge is obtained by rearranging the definition of α to obtain the following definition of e in terms of α and h:

- e=2αhμ0c0=2αhε0c0.displaystyle e=sqrt frac 2alpha hmu _0c_0=sqrt 2alpha hvarepsilon _0c_0.

Bohr magneton and nuclear magneton

The Bohr magneton and the nuclear magneton are units which are used to describe the magnetic properties of the electron and atomic nuclei respectively. The Bohr magneton is the magnetic moment which would be expected for an electron if it behaved as a spinning charge according to classical electrodynamics. It is defined in terms of the reduced Planck constant, the elementary charge and the electron mass, all of which depend on the Planck constant: the final dependence on h1/2 (r2 > 0.995) can be found by expanding the variables.

- μB=eℏ2me=c0α5h32π2μ0R∞2displaystyle mu _rm B=frac ehbar 2m_rm e=sqrt frac c_0alpha ^5h32pi ^2mu _0R_infty ^2

The nuclear magneton has a similar definition, but corrected for the fact that the proton is much more massive than the electron. The ratio of the electron relative atomic mass to the proton relative atomic mass can be determined experimentally to a high level of precision (ur = 6989950000000000000♠9.5×10−11).

- μN=μBAr(e)Ar(p)displaystyle mu _rm N=mu _rm Bfrac A_rm r(rm e)A_rm r(rm p)

Determination

| Method | Value of h (6966100000000000000♠10−34 J⋅s) | Relative uncertainty | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kibble (watt) balance | 7000662606889000000♠6.62606889(23) | 6992340000000000000♠3.4×10−8 | [38][39][40] |

| X-ray crystal density | 7000662607450000000♠6.6260745(19) | 6993290000000000000♠2.9×10−7 | [41] |

| Josephson constant | 7000662606780000000♠6.6260678(27) | 6993409999999999999♠4.1×10−7 | [42][43] |

| Magnetic resonance | 7000662607240000000♠6.6260724(57) | 6993859999999999999♠8.6×10−7 | [44][45] |

| Faraday constant | 7000662606570000000♠6.6260657(88) | 1.3×10−6 | [46] |

CODATA 2010 | 7000662606957000000♠6.62606957(29) | 4.4×10−8 | [47] |

| Kibble balance with superconducting magnet | 7000662606979000000♠6.62606979(30) | 4.5×10−8 | [5] |

| The nine recent determinations of the Planck constant cover five separate methods. Where there is more than one recent determination for a given method, the value of h given here is a weighted mean of the results, as calculated by CODATA. | |||

In principle, the Planck constant could be determined by examining the spectrum of a black-body radiator or the kinetic energy of photoelectrons, and this is how its value was first calculated in the early twentieth century. In practice, these are no longer the most accurate methods. The CODATA value quoted here is based on three Kibble balance measurements of KJ2RK and one inter-laboratory determination of the molar volume of silicon,[48] but is mostly determined by a 2007 Kibble balance measurement made at the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).[40] Five other measurements by three different methods were initially considered, but not included in the final refinement as they were too imprecise to affect the result.

There are both practical and theoretical difficulties in determining h. The practical difficulties can be illustrated by the fact that the two most accurate methods, the Kibble balance and the X-ray crystal density method, do not appear to agree with one another. The most likely reason is that the measurement uncertainty for one (or both) of the methods has been estimated too low – it is (or they are) not as precise as is currently believed – but for the time being there is no indication which method is at fault.

The theoretical difficulties arise from the fact that all of the methods except the X-ray crystal density method rely on the theoretical basis of the Josephson effect and the quantum Hall effect. If these theories are slightly inaccurate – though there is no evidence at present to suggest they are – the methods would not give accurate values for the Planck constant. More importantly, the values of the Planck constant obtained in this way cannot be used as tests of the theories without falling into a circular argument. There are other statistical ways of testing the theories, and the theories have yet to be refuted.[48]

Josephson constant

The Josephson constant KJ relates the potential difference U generated by the Josephson effect at a "Josephson junction" with the frequency ν of the microwave radiation. The theoretical treatment of Josephson effect suggests very strongly that KJ = 2e/h.

- KJ=νU=2ehdisplaystyle K_rm J=frac nu U=frac 2eh,

The Josephson constant may be measured by comparing the potential difference generated by an array of Josephson junctions with a potential difference which is known in SI volts. The measurement of the potential difference in SI units is done by allowing an electrostatic force to cancel out a measurable gravitational force. Assuming the validity of the theoretical treatment of the Josephson effect, KJ is related to the Planck constant by

- h=8αμ0c0KJ2.displaystyle h=frac 8alpha mu _0c_0K_rm J^2.

Kibble balance

A Kibble balance (formerly known as a watt balance)[49] is an instrument for comparing two powers, one of which is measured in SI watts and the other of which is measured in conventional electrical units. From the definition of the conventional watt W90, this gives a measure of the product KJ2RK in SI units, where RK is the von Klitzing constant which appears in the quantum Hall effect. If the theoretical treatments of the Josephson effect and the quantum Hall effect are valid, and in particular assuming that RK = h/e2, the measurement of KJ2RK is a direct determination of the Planck constant.

- h=4KJ2RK.displaystyle h=frac 4K_rm J^2R_rm K.

Magnetic resonance

The gyromagnetic ratio γ is the constant of proportionality between the frequency ν of nuclear magnetic resonance (or electron paramagnetic resonance for electrons) and the applied magnetic field B: ν = γB. It is difficult to measure gyromagnetic ratios precisely because of the difficulties in precisely measuring B, but the value for protons in water at 7002298150000000000♠25 °C is known to better than one part per million. The protons are said to be "shielded" from the applied magnetic field by the electrons in the water molecule, the same effect that gives rise to chemical shift in NMR spectroscopy, and this is indicated by a prime on the symbol for the gyromagnetic ratio, γ′p. The gyromagnetic ratio is related to the shielded proton magnetic moment μ′p, the spin number I (I = 1⁄2 for protons) and the reduced Planck constant.

- γp′=μp′Iℏ=2μp′ℏdisplaystyle gamma _rm p^prime =frac mu _rm p^prime Ihbar =frac 2mu _rm p^prime hbar

The ratio of the shielded proton magnetic moment μ′p to the electron magnetic moment μe can be measured separately and to high precision, as the imprecisely known value of the applied magnetic field cancels itself out in taking the ratio. The value of μe in Bohr magnetons is also known: it is half the electron g-factor ge. Hence

- μp′=μp′μegeμB2displaystyle mu _rm p^prime =frac mu _rm p^prime mu _rm efrac g_rm emu _rm B2

- γp′=μp′μegeμBℏ.displaystyle gamma _rm p^prime =frac mu _rm p^prime mu _rm efrac g_rm emu _rm Bhbar .

A further complication is that the measurement of γ′p involves the measurement of an electric current: this is invariably measured in conventional amperes rather than in SI amperes, so a conversion factor is required. The symbol Γ′p-90 is used for the measured gyromagnetic ratio using conventional electrical units. In addition, there are two methods of measuring the value, a "low-field" method and a "high-field" method, and the conversion factors are different in the two cases. Only the high-field value Γ′p-90(hi) is of interest in determining the Planck constant.

- γp′=KJ−90RK−90KJRKΓp−90′(hi)=KJ−90RK−90e2Γp−90′(hi)displaystyle gamma _rm p^prime =frac K_rm J-90R_rm K-90K_rm JR_rm KGamma _rm p-90^prime (rm hi)=frac K_rm J-90R_rm K-90e2Gamma _rm p-90^prime (rm hi)

Substitution gives the expression for the Planck constant in terms of Γ′p-90(hi):

- h=c0α2ge2KJ−90RK−90R∞Γp−90′(hi)μp′μe.displaystyle h=frac c_0alpha ^2g_rm e2K_rm J-90R_rm K-90R_infty Gamma _rm p-90^prime (rm hi)frac mu _rm p^prime mu _rm e.

Faraday constant

The Faraday constant F is the charge of one mole of electrons, equal to the Avogadro constant NA multiplied by the elementary charge e. It can be determined by careful electrolysis experiments, measuring the amount of silver dissolved from an electrode in a given time and for a given electric current. In practice, it is measured in conventional electrical units, and so given the symbol F90. Substituting the definitions of NA and e, and converting from conventional electrical units to SI units, gives the relation to the Planck constant.

- h=c0MuAr(e)α2R∞1KJ−90RK−90F90displaystyle h=frac c_0M_rm uA_rm r(rm e)alpha ^2R_infty frac 1K_rm J-90R_rm K-90F_90

X-ray crystal density

The X-ray crystal density method is primarily a method for determining the Avogadro constant NA but as the Avogadro constant is related to the Planck constant it also determines a value for h. The principle behind the method is to determine NA as the ratio between the volume of the unit cell of a crystal, measured by X-ray crystallography, and the molar volume of the substance. Crystals of silicon are used, as they are available in high quality and purity by the technology developed for the semiconductor industry. The unit cell volume is calculated from the spacing between two crystal planes referred to as d220. The molar volume Vm(Si) requires a knowledge of the density of the crystal and the atomic weight of the silicon used. The Planck constant is given by

- h=MuAr(e)c0α2R∞2d2203Vm(Si).displaystyle h=frac M_rm uA_rm r(rm e)c_0alpha ^2R_infty frac sqrt 2d_220^3V_rm m(rm Si).

Particle accelerator

The experimental measurement of the Planck constant in the Large Hadron Collider laboratory was carried out in 2011. The study called PCC using a giant particle accelerator helped to better understand the relationships between the Planck constant and measuring distances in space.[citation needed]

Fixation

As mentioned above, the numerical value of the Planck constant depends on the system of units used to describe it. Its value in SI units is known to 12 parts per billion but its value in atomic units is known exactly, because of the way the scale of atomic units is defined. The same is true of conventional electrical units, where the Planck constant (denoted h90 to distinguish it from its value in SI units) is given by

- h90=4KJ−902RK−90displaystyle h_90=frac 4K_J-90^2R_K-90

with KJ–90 and RK–90 being exactly defined constants. Atomic units and conventional electrical units are very useful in their respective fields, because the uncertainty in the final result does not depend on an uncertain conversion factor, only on the uncertainty of the measurement itself.

It is currently planned to redefine certain of the SI base units in terms of fundamental physical constants.[7] This has already been done for the metre, which since 1983 has been defined in terms of a fixed value of the speed of light. The most urgent unit on the list for redefinition is the kilogram, whose value has been fixed for all science (since 1889) by the mass of a small cylinder of platinum–iridium alloy kept in a vault just outside Paris. While nobody knows if the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram has changed since 1889 – the value 1 kg of its mass expressed in kilograms is by definition unchanged and therein lies one of the problems – it is known that over such a timescale the many similar Pt–Ir alloy cylinders kept in national laboratories around the world have changed their relative masses by several tens of parts per billion, however carefully they are stored. A change of several tens of micrograms in one kilogram is equivalent to the current uncertainty in the value of the Planck constant in SI units.

The legal process to change the definition of the kilogram to one based on a fixed value of the Planck constant is already underway.[50] The 24th and 25th General Conferences on Weights and Measures (CGPM) in 2011 and 2014 approved of the redefinition in principle, but were not satisfied with the measurement uncertainty of the Planck constant. The limits they specified were reached in 2016,[7] and the redefinition is scheduled to occur on 16 November 2018, during the 26th CGPM.[51]

Kibble balances already measure mass in terms of the Planck constant: at present, standard kilogram prototypes are taken as fixed masses and the measurement is performed to determine the Planck constant but, once the Planck constant is fixed in SI units, the same experiment would be a measurement of the mass. The relative uncertainty in the measurement would remain the same.

Mass standards could also be constructed from silicon crystals or by other atom-counting methods. Such methods require a knowledge of the Avogadro constant, which fixes the proportionality between atomic mass and macroscopic mass but, with a defined value of the Planck constant, NA would be known to the same level of uncertainty (if not better) than current methods of comparing macroscopic mass.

See also

- Basic concepts of quantum mechanics

- Planck units

- Wave–particle duality

- CODATA 2018

Notes

^ Set on 20 November 2018, by the CGPM to this exact value, with this value to take effect 22 May 2019, as explained in the other references.

^ "Resolutions of the 26th CGPM" (PDF). BIPM. 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2018-11-20..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Ghosh, Pallab (2018-11-16). "Kilogram gets a new definition". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

^ Veritasium (2018-11-15), The kg is dead, long live the kg, retrieved 2018-11-16

^ ab Schlamminger, S.; Haddad, D.; Seifert, F.; Chao, L. S.; Newell, D. B.; Liu, R.; Steiner, R. L.; Pratt, J. R. (2014). "Determination of the Planck constant using a watt balance with a superconducting magnet system at the National Institute of Standards and Technology". Metrologia. 51 (2): S15. arXiv:1401.8160. Bibcode:2014Metro..51S..15S. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/51/2/S15. ISSN 0026-1394.

^ abcd Barry N. Taylor of the Data Center in close collaboration with Peter J. Mohr of the Physical Measurement Laboratory's Atomic Physics Division, Termed the "2014 CODATA recommended values," they are generally recognized worldwide for use in all fields of science and technology. The values became available on 25 June 2015 and replaced the 2010 CODATA set. They are based on all of the data available through 31 December 2014. Available: http://physics.nist.gov

^ abc "Universe's Constants Now Known with Sufficient Certainty to Completely Redefine the International System of Units" (Press release). NIST. 22 November 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ New York Times "The Latest: Landmark Change to Kilogram Approved" Nov 16 2018; https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2018/11/16/world/europe/ap-eu-france-updating-the-kilo-the-latest.html

^ "Resolutions of the 26th CGPM" (PDF). BIPM. 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

^ Ghosh, Pallab (2018-11-16). "Kilogram gets a new definition". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

^ Veritasium (2018-11-15), The kg is dead, long live the kg, retrieved 2018-11-16

^ R. Bowley; M. Sánchez (1999), Introductory Statistical Mechanics (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850576-1

^ abcde Planck, Max (1901), "Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum" (PDF), Ann. Phys., 309 (3): 553–63, Bibcode:1901AnP...309..553P, doi:10.1002/andp.19013090310. English translation: "On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum Archived 2008-04-18 at the Wayback Machine."."Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-10-13.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Kragh, Helge (1 December 2000), Max Planck: the reluctant revolutionary, PhysicsWorld.com

^ Kragh, Helge (1999), Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, p. 62, ISBN 978-0-691-09552-3

^ Planck, Max (2 June 1920), The Genesis and Present State of Development of the Quantum Theory (Nobel Lecture)

^ Previous Solvay Conferences on Physics, International Solvay Institutes, archived from the original on 16 December 2008, retrieved 12 December 2008

^ ab See, e.g., Arrhenius, Svante (10 December 1922), Presentation speech of the 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics

^ abc Lenard, P. (1902), "Ueber die lichtelektrische Wirkung", Ann. Phys., 313 (5): 149–98, Bibcode:1902AnP...313..149L, doi:10.1002/andp.19023130510

^ Einstein, Albert (1905), "Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt" (PDF), Ann. Phys., 17 (6): 132–48, Bibcode:1905AnP...322..132E, doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607

^ abc Millikan, R. A. (1916), "A Direct Photoelectric Determination of Planck's h", Phys. Rev., 7 (3): 355–88, Bibcode:1916PhRv....7..355M, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.7.355

^ Isaacson, Walter (2007-04-10), Einstein: His Life and Universe, ISBN 978-1-4165-3932-2, pp. 309–314.

^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

^ Smith, Richard (1962), "Two Photon Photoelectric Effect", Physical Review, 128 (5): 2225, Bibcode:1962PhRv..128.2225S, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.128.2225.

Smith, Richard (1963), "Two-Photon Photoelectric Effect", Physical Review, 130 (6): 2599, Bibcode:1963PhRv..130.2599S, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.130.2599.4.

^ Bohr, Niels (1913), "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules", Phil. Mag., 6th Series, 26 (153): 1–25, doi:10.1080/14786441308634993

^ Mohr, J. C.; Phillips, W. D. (2015). "Dimensionless Units in the SI". Metrologia. 52 (1): 40–47.

^ Mills, I. M. (2016). "On the units radian and cycle for the quantity plane angle". Metrologia. 53 (3): 991–997.

^ Nature (2017) ‘’A Flaw in the SI system,’' Volume 548, Page 135

^ Maxwell J.C. (1873) A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, Oxford University Press

^ Giuseppe Morandi; F. Napoli; E. Ercolessi (2001), Statistical mechanics: an intermediate course, p. 84, ISBN 978-981-02-4477-4

^ Einstein, Albert (2003), "Physics and Reality" (PDF), Daedalus, 132 (4): 24, doi:10.1162/001152603771338742, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-15,The question is first: How can one assign a discrete succession of energy value Hσ to a system specified in the sense of classical mechanics (the energy function is a given function of the coordinates qr and the corresponding momenta pr)? The Planck constant h relates the frequency Hσ/h to the energy values Hσ. It is therefore sufficient to give to the system a succession of discrete frequency values.

^ "New Measurement Will Help Redefine International Unit of Mass". National Institute of Standards and Technology. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

^

Draft Resolution A "On the revision of the International System of units (SI)" to be submitted to the CGPM at its 26th meeting (2018) (PDF)

^ "CODATA recommended values".

^

Newell, David B.; Franco Cabiati; Joachim Fischer; Kenichi Fujii; Saveley G. Karshenboim; Helen S. Margolis; Estefania de Mirandes; Peter J. Mohr; Francois Nez; Krzysztof Pachucki; Terry J. Quinn; Barry N. Taylor; Meng Wang; Barry Wood; Zhonghua Zhang (2017-10-20). "The CODATA 2017 Values of h, e, k, and NA for the Revision of the SI". Metrologia. Bibcode:2018Metro..55L..13N. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/aa950a. Retrieved 2017-11-08.

^ Mohr, Peter J.; Newell, David B.; Taylor, Barry N. (2016). "CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2014". Reviews of Modern Physics. 88 (3): 035009. arXiv:1507.07956. Bibcode:2016RvMP...88c5009M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.150.1225. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.88.035009.

^ The main exceptions are the Newtonian constant of gravitation G (ur = 6995470000000000000♠4.7×10−5) and the gas constant R (ur = 6993570000000000000♠5.7×10−7). The uncertainty in the value of the gas constant also affects those physical constants which are related to it, such as the Boltzmann constant and the Loschmidt constant.

^ Kibble, B P; Robinson, I A; Belliss, J H (1990), "A Realization of the SI Watt by the NPL Moving-coil Balance", Metrologia, 27 (4): 173–92, Bibcode:1990Metro..27..173K, doi:10.1088/0026-1394/27/4/002

^ Steiner, R.; Newell, D.; Williams, E. (2005), "Details of the 1998 Watt Balance Experiment Determining the Planck Constant" (PDF), Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, 110 (1): 1–26, doi:10.6028/jres.110.003, PMC 4849564, PMID 27308100, archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-04-24

^ ab Steiner, Richard L.; Williams, Edwin R.; Liu, Ruimin; Newell, David B. (2007), "Uncertainty Improvements of the NIST Electronic Kilogram", IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 56 (2): 592–96, doi:10.1109/TIM.2007.890590

^ Fujii, K.; Waseda, A.; Kuramoto, N.; Mizushima, S.; Becker, P.; Bettin, H.; Nicolaus, A.; Kuetgens, U.; Valkiers, S.; Taylor, P.; Debievre, P.; Mana, G.; Massa, E.; Matyi, R.; Kessler, E.G.; Hanke, M. (2005), "Present state of the Avogadro constant determination from silicon crystals with natural isotopic compositions", IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 54 (2): 854–59, doi:10.1109/TIM.2004.843101

^ Sienknecht, Volkmar; Funck, Torsten (1985), "Determination of the SI Volt at the PTB", IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 34 (2): 195–98, doi:10.1109/TIM.1985.4315300. Sienknecht, V.; Funck, T. (1986), "Realization of the SI Unit Volt by Means of a Voltage Balance", Metrologia, 22 (3): 209–12, Bibcode:1986Metro..22..209S, doi:10.1088/0026-1394/22/3/018. Funck, T.; Sienknecht, V. (1991), "Determination of the volt with the improved PTB voltage balance", IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 40 (2): 158–61, doi:10.1109/TIM.1990.1032905

^ Clothier, W. K.; Sloggett, G. J.; Bairnsfather, H.; Currey, M. F.; Benjamin, D. J. (1989), "A Determination of the Volt", Metrologia, 26 (1): 9–46, Bibcode:1989Metro..26....9C, doi:10.1088/0026-1394/26/1/003

^ Kibble, B P; Hunt, G J (1979), "A Measurement of the Gyromagnetic Ratio of the Proton in a Strong Magnetic Field", Metrologia, 15 (1): 5–30, Bibcode:1979Metro..15....5K, doi:10.1088/0026-1394/15/1/002

^ Liu Ruimin; Liu Hengji; Jin Tiruo; Lu Zhirong; Du Xianhe; Xue Shouqing; Kong Jingwen; Yu Baijiang; Zhou Xianan; Liu Tiebin; Zhang Wei (1995), "A Recent Determination for the SI Values of γ′p and 2e/h at NIM", Acta Metrologica Sinica, 16 (3): 161–68

^ Bower, V. E.; Davis, R. S. (1980), "The Electrochemical Equivalent of Pure Silver: A Value of the Faraday Constant", Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, 85 (3): 175–91, doi:10.6028/jres.085.009

^ P.J. Mohr, B.N. Taylor, and D.B. Newell (2011), "The 2010 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" (Web Version 6.0). This database was developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. Available: http://physics.nist.gov [Thursday, 02-Jun-2011 21:00:12 EDT]. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899.

^ ab Mohr, Peter J.; Taylor, Barry N.; Newell, David B. (2008). "CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2006". Reviews of Modern Physics. 80 (2): 633–730. arXiv:0801.0028. Bibcode:2008RvMP...80..633M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.633.

Direct link to value.

^ Materese, Robin (2018-05-14). "Kilogram: The Kibble Balance". NIST. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

^ 94th Meeting of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (2005). Recommendation 1: Preparative steps towards new definitions of the kilogram, the ampere, the kelvin and the mole in terms of fundamental constants Archived 2006-10-03 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Milton, Martin (14 November 2016). Highlights in the work of the BIPM in 2016 (PDF). SIM XXII General Assembly. Montevideo, Uruguay. p. 10. The conference runs from 13–16 November; the redefinition is scheduled for the morning of the last day.

References

Barrow, John D. (2002), The Constants of Nature; From Alpha to Omega – The Numbers that Encode the Deepest Secrets of the Universe, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-375-42221-8

External links

- Quantum of Action and Quantum of Spin – Numericana

Moriarty, Philip; Eaves, Laurence; Merrifield, Michael (2009). "h Planck's Constant". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.- A pdf file explaining the relation between h and ħ, their units, and the history of their introduction Link

Videos

- The BIPM YouTube channel

- "The role of the Planck constant in physics" - presentation at 26th CGPM meeting at Versailles, France, November 2018 when voting took place.

![[hat p_i,hat x_j]=-ihbar delta _ij,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6de152aa445b7ca6653b9dd087ad604c2b8bf0e)