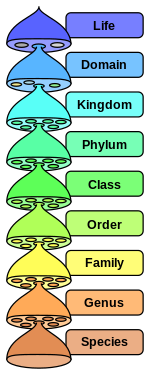

The hierarchy of biological classification's eight major taxonomic ranks. A family contains one or more genera. Intermediate minor rankings are not shown.

A genus (pl. genera [1] in biology. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial species name for each species within the genus.

E.g. Panthera leo (lion) and Panthera onca (jaguar) are two species within the genus Panthera . Panthera is a genus within the family Felidae. The composition of a genus is determined by a taxonomist. The standards for genus classification are not strictly codified, so different authorities often produce different classifications for genera. There are some general practices used, however,[2] including the idea that a newly defined genus should fulfill these three criteria to be descriptively useful:

[3] ).reasonable compactness – a genus should not be expanded needlessly; and distinctness – with respect to evolutionarily relevant criteria, i.e. ecology, morphology, or biogeography; DNA sequences are a consequence rather than a condition of diverging evolutionary lineages except in cases where they directly inhibit gene flow (e.g. postzygotic barriers). Moreover, genera should be composed of phylogenetic units of the same kind as other (analogous) genera.[3]

Contents 1 Name 2 Use 2.1 Use in nomenclature 2.2 The type concept 2.3 Categories of generic name 2.4 Identical names (homonyms) 2.5 Use in higher classifications 3 Numbers of accepted genera 4 Genus size 5 See also 6 Notes 7 References 8 External links Name The term comes from the Latin genus ("origin, type, group, race"),[4] a noun form cognate with gignere ("to bear; to give birth to"). Linnaeus popularized its use in his 1753 Species Plantarum , but the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708) is considered "the founder of the modern concept of genera".[5]

Use The scientific name of a genus is also called the generic name ; it is always capitalised. It plays a pivotal role in binomial nomenclature, the system of naming organisms.

Use in nomenclature Main articles: Binomial nomenclature, Taxonomy (biology), Author citation (zoology), and Author citation (botany)

The rules for the scientific names of organisms are laid down in the Nomenclature Codes, giving each species a single unique name which is Latin in form and, by contrast with a common name, is language-independent. Except for viruses, the standard format for a species name comprises a generic name (which indicates the genus to which the species belongs) followed by a specific epithet. For example, the gray wolf's binomial name is Canis lupus ,Canis (Lat. "dog") being the generic name shared by the wolf's close relatives and lupus (Lat. "wolf") being the specific name particular to the wolf; a botanical example would be Hibiscus arnottianus , a species of hibiscus native to Hawaii. The specific name is written in lower-case and may be followed by subspecies names in zoology or a variety of infraspecific names in botany. When the generic name is already known from context, it may be shortened to its initial letter, for example C. lupus in place of Canis lupus . Where species are further subdivided, the generic name (or its abbreviated form) still forms the leading portion of the scientific name, for example Canis lupus familiaris Hibiscus arnottianus ssp. immaculatus

The scientific names of species viruses are not binomial in form, but are descriptive, and may or may not incorporate a reference to their containing genus. For example both the Everglades virus and the Ross River virus are ascribed to the virus genus Alphavirus , while the virus genus Salmonivirus contains species with the names "Salmonid herpesvirus 1", "Salmonid herpesvirus 2" and "Salmonid herpesvirus 3".

As with scientific names at other ranks, in all groups other than viruses, names of genera may be cited with their authorities, typically in the form "author, year" in zoology, and "standard abbreviated author name" in botany. Thus in the examples above, the genus Canis would be cited in full as "Canis Linnaeus, 1758" (zoological usage), while Hibiscus , also first established by Linnaeus but in 1753, is simply "Hibiscus L." (botanical usage).

The type concept See also: Type genus, Type species, and Type specimen

Each genus should have a designated type, although in practice there is a backlog of older names without one. In zoology, this is the type species and the generic name is permanently associated with the type specimen of its type species. Should the specimen turn out to be assignable to another genus, the generic name linked to it becomes a junior synonym and the remaining taxa in the former genus need to be reassessed.

Categories of generic name In zoological usage, taxonomic names, including those of genera, are classified as "available" or "unavailable". Available names are those published in accordance with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and not otherwise suppressed by subsequent decisions of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN); the earliest such name for any taxon (for example, a genus) should then be selected as the "valid" (=current, or accepted) name for the taxon in question. It therefore follows that there will be more available names than valid names at any point in time, which names are currently in use depending on the judgement of taxonomists in either either combining taxa described under multiple names, or splitting taxa which may bring available names previously treated as synonyms back into use. "Unavailable" names in zoology comprise names that either were not published according to the provisions of the ICZN Code, or have subsequently been suppressed; they include (for example) incorrect original or subsequent spellings, names published only in a thesis, generic names published after 1930 with no type species indicated, and more.[6]

In botany, similar concepts exist but with different labels. The botanical equivalent of zoology's "available name" is a validly published name. An invalidly published name is a nomen invalidum or nom. inval. ; a rejected name is a nomen rejiciendum or nom. rej. ; a later homonym of a validly published name is a nomen illegitimum or nom. illeg. ; for a full list refer the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICNafp) and the work cited above by Hawksworth, 2010.[6] In place of the "valid taxon" in zoology, the nearest equivalent in botany is "correct name" or "current name" which can, again, differ or change with alternative taxonomic treatments or new information that results in previously accepted genera being combined or split.

Prokaryote and virus Codes of Nomenclature also exist which serve as a reference for designating currently accepted genus names as opposed to others which may be either reduced to synonymy, or, in the case of prokaryotes, relegated to a status of "names without standing in prokaryotic nomenclature".

An available (zoology) or validly published (botany) name that has been historically applied to a genus but is not regarded as the accepted (current/valid) name for the taxon is termed a synonym ; some authors also include unavailable names in lists of synonyms as well as available names, such as misspellings, names previously published without fulfilling all of the requirements of the relevant nomenclatural Code, and rejected or suppressed names. A particular genus name may have zero to many synonyms, the latter case generally if the genus has been known for a long time and redescribed as new by a range of subsequent workers, or if a range of genera previously considered separate taxa have subsequently been consolidated into one. For example, the World Register of Marine Species presently lists 8 genus-level synonyms for the sperm whale genus Physeter Linnaeus, 1758,[7] and 13 for the bivalve genus Pecten O.F. Müller, 1776.[8]

Identical names (homonyms) Within the same kingdom one generic name can apply to one genus only. However, many names have been assigned (usually unintentionally) to two or more different genera. For example, the platypus belongs to the genus Ornithorhynchus although George Shaw named it Platypus in 1799 (these two names are thus synonyms )Platypus had already been given to a group of ambrosia beetles by Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Herbst in 1793. A name that means two different things is a homonym Ornithorhynchus in 1800.

However, a genus in one kingdom is allowed to bear a scientific name that is in use as a generic name (or the name of a taxon in another rank) in a kingdom that is governed by a different nomenclature code. Names with the same form but applying to different taxa are called "homonyms". Although this is discouraged by both the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, there are some five thousand such names in use in more than one kingdom. For instance,

Anura is the name of the order of frogs but also is the name of a non-current genus of plants;Aotus is the generic name of both golden peas and night monkeys;Oenanthe is the generic name of both wheatears and water dropworts;Prunella is the generic name of both accentors and self-heal; andProboscidea is the order of elephants and the genus of devil's claws.The name of the genus Paramecia (an extinct red alga) is also the plural of the name of the genus Paramecium (which is in the SAR supergroup), which can also lead to confusion. A list of generic homonyms (with their authorities), including both available (validly published) and selected unavailable names, has been compiled by the Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera (IRMNG).[9]

Use in higher classifications The type genus forms the base for higher taxonomic ranks, such as the family name Canidae ("Canids") based on Canis . However, this does not typically ascend more than one or two levels: the order to which dogs and wolves belong is Carnivora ("Carnivores").

Numbers of accepted genera The numbers of either accepted, or all published genus names is not known precisely although the latter value has been estimated by Rees et al., 2017[10] at approximately 510,000 as at end 2016, increasing at some 2,500 per year. "Official" registers of taxon names at all ranks, including genera, exist for a few groups only such as viruses[1] and prokaryotes[11] , while for others there are compendia with no "official" standing such as Index Fungorum for Fungi,[12] , Index Nominum Algarum [13] and AlgaeBase[14] for algae, Index Nominum Genericorum [15] and the International Plant Names Index[16] for plants in general, and ferns through angiosperms, respectively, and Nomenclator Zoologicus [17] and the Index to Organism Names[18] for zoological names.

A deduplicated list of genus names covering all taxonomic groups, compiled from resources such as the above as well as other literature sources, created as the "Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera" (IRMNG), is estimated to contain around 95% of all published names at generic level, and lists approximately 488,500 genus names in its March 2018 release;[9] of these, a little over 361,000 are presently flagged "accepted" although this figure is likely to be an overestimate since the "accepted" category in IRMNG includes both names known to be current, plus a component not yet assessed for taxonomic status. These "accepted" genus names are divided into 269,000 currently listed as non-fossil (either extant, or presumed extant i.e. not explicitly stated as fossil), while 92,000 are listed as extinct (=fossil). Included in the value of 269,000 extant, notionally accepted genus names in the March 2018 edition of IRMNG are 217,811 genera of animals (kingdom Animalia), 28,391 Plantae (land plants and non-Chromistan algae), 10,005 Fungi, 7,594 Chromista, 2,462 Protozoa, 2,204 Prokaryotes (2,121 Bacteria plus 103 Archaea) and 513 Viruses, although totals for the two latter groups will be incomplete for the period 2011-current on account of the absence of more recent IRMNG updates for those groups in particular[10] ; as at March 2018, King et al.[19] give the total number of recognised virus genera as 803. (For prokaryotes, see note).[a]

By comparison, the 2018 annual edition of the Catalogue of Life (estimated >90% complete, for extant species in the main) contains currently "accepted" 175,363 genus names for 1,744,204 living and 59,284 extinct species,[20] also including genus names only (no species) for some groups.

Genus size

Number of reptile genera with a given number of species. Most genera have only one or a few species but a few may have hundreds. Based on data from the Reptile Database (as of May 2015).

The number of species in genera varies considerably among taxonomic groups. For instance, among (non-avian) reptiles, which have about 1180 genera, the most (>300) have only 1 species, ~360 have between 2 and 4 species, 260 have 5-10 species, ~200 have 11-50 species, and only 27 genera have more than 50 species (see figure).[21] However, some insect genera such as the bee genera Lasioglossum and Andrena have over 1000 species each. The largest flowering plant genus, Astragalus , contains over 3,000 species.[22]

Which species are assigned to a genus is somewhat arbitrary. Although all species within a genus are supposed to be "similar" there are no objective criteria for grouping species into genera. There is much debate among zoologists whether large, species-rich genera should be maintained, as it is extremely difficult to come up with identification keys or even character sets that distinguish all species. Hence, many taxonomists argue in favor of breaking down large genera. For instance, the lizard genus Anolis has been suggested to be broken down into 8 or so different genera which would bring its ~400 species to smaller, more manageable subsets.[23]

See also List of the largest genera of flowering plants Notes ^ According to the LPSN website, as at May 2017 a total of 2,854 prokaryote genus names were validly published and/or included in the "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature", however this total does not distinguish between currently accepted names and synonyms. In addition, a small number of cyanobacterial genus names accepted by phycologists (in botany) but not in bacteriology are excluded, including the ecologically important genera Microcystis Kützing and Planktothrix Anagnostidis & Komárek, 1988. References ^ a b "ICTV Taxonomy". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2018 . .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em^ Gill, F. B.; Slikas, B.; Sheldon, F. H. (2005). "Phylogeny of titmice (Paridae): II. Species relationships based on sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene". Auk . 122 (1): 121–143. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[0121:POTPIS]2.0.CO;2. ^ a b de la Maza-Benignos, Mauricio; Lozano-Vilano, Ma. de Lourdes; García-Ramírez, María Elena (December 2015). "Response paper: Morphometric article by Mejía et al. 2015 alluding genera Herichthys and Nosferatu displays serious inconsistencies". Neotropical Ichthyology . 13 (4): 673–676. doi:10.1590/1982-0224-20150066. ^ Merriam Webster Dictionary ^ Stuessy, T. F. (2009). Plant Taxonomy: The Systematic Evaluation of Comparative Data (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780231147125. ^ a b D. L. Hawksworth (2010). Terms Used in Bionomenclature: The Naming of Organisms and Plant Communities : Including Terms Used in Botanical, Cultivated Plant, Phylogenetic, Phytosociological, Prokaryote (bacteriological), Virus, and Zoological Nomenclature . GBIF. pp. 1–215. ISBN 978-87-92020-09-3. ^ World Register of Marine Species: Physeter Linnaeus, 1758 ^ World Register of Marine Species: Pecten O. F. Müller, 1776 ^ a b "IRMNG: Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera". www.irmng.org . Retrieved 2016-11-17 . ^ a b Rees, Tony; Vandepitte, Leen; Decock, Wim; Vanhoorne, Bart (2017). "IRMNG 2006–2016: 10 Years of a Global Taxonomic Database". Biodiversity Informatics . 12 : 1–44. doi:10.17161/bi.v12i0.6522. ^ List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature ^ Index Fungorum ^ Index Nominum Algarum ^ AlgaeBase ^ Index Nominum Genericorum ^ The International Plant Names Index ^ Nomenclator Zoologicus ^ Index to Organism Names ^ King, Andrew M. Q.; et al. (2018). "Changes to taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2018)". Archives of Virology : 1–31. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-3847-1. ^ Information: Catalogue of Life: 2018 Annual Checklist ^ The Reptile Database ^ Frodin, David G. (2004). "History and concepts of big plant genera". Taxon . 53 (3): 753–776. doi:10.2307/4135449. JSTOR 4135449. ^ Nicholson, K. E.; Crother, B. I.; Guyer, C.; Savage, J.M. (2012). "It is time for a new classification of anoles (Squamata: Dactyloidae)" (PDF) . Zootaxa . 3477 : 1–108. External links Fauna Europaea Database for Taxonomy Taxonomic ranks

Domain /SuperkingdomKingdom Subkingdom Infrakingdom/Branch Superphylum/Superdivision Phylum/Division Subphylum Infraphylum Microphylum Superclass Class Subclass Infraclass Parvclass Magnorder Superorder Order Suborder Infraorder Parvorder Section (zoo. ) Superfamily Family Subfamily Infrafamily Supertribe Tribe Subtribe Infratribe Genus Subgenus Section (bot. ) Series (bot. ) Species Subspecies Variety Form