Draža Mihailović

Draža Mihailović | |

|---|---|

Mihailović during World War II | |

| Birth name | Dragoljub Mihailović |

| Nickname(s) | "Uncle Draža" |

| Born | (1893-04-27)27 April 1893 Ivanjica, Kingdom of Serbia |

| Died | 17 July 1946(1946-07-17) (aged 53) Belgrade, Serbia, Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1910–1945 |

| Rank | Army General[1] |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović[a] (Serbian Cyrillic: Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II and convicted war criminal. A staunch royalist, he retreated to the mountains near Belgrade when the Germans overran Yugoslavia in April 1941 and there he organized bands of guerrillas known as the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army.

The organisation is commonly known as the Chetniks, although the name of the organisation was later changed to the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland (JVUO, ЈВУО).[6] Founded as the first Yugoslav resistance movement, it was royalist and nationalist, as opposed to the other, Josip Broz Tito's Partisans who were communist. Initially, the two groups operated in parallel, but by late 1941 began fighting each other in the attempt to gain control of post-war Yugoslavia. Many Chetnik groups collaborated or established modus vivendi with the Axis powers. Mihailović himself collaborated with Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić at the end of the war. After the war, Mihailović was captured by the communists. He was tried and convicted of high treason and war crimes by the communist authorities of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, and executed by firing squad in Belgrade. The nature and extent of his responsibility for collaboration and ethnic massacres remains controversial. On 14 May 2015, Mihailović was rehabilitated after a ruling by the Supreme Court of Cassation, the highest appellate court in Serbia.

Contents

1 Early life and military career

2 World War II

2.1 Formation of the Chetniks

2.2 Conflicts with Axis troops and Partisans

2.3 Activities in Montenegro and the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia

2.4 Terror tactics and cleansing actions

3 Relations with the British

4 Defeat in the battle of the Neretva

5 Allied support shifts

6 Defeat in 1944–45

7 Capture, trial and execution

8 Rehabilitation

9 Family

10 Legacy

11 See also

12 Notes

13 Citations

13.1 Footnotes

13.2 References

14 Further reading

15 External links

Early life and military career

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was born on 27 April 1893 in Ivanjica, Kingdom of Serbia to Mihailo and Smiljana Mihailović (née Petrović).[7] His father was a court clerk. Orphaned at seven years of age, Mihailović was raised by his paternal uncle in Belgrade.[8] As both of his uncles were military officers, Mihailović himself joined the Serbian Military Academy in October 1910. He fought as a cadet in the Serbian Army during the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 and was awarded the Silver Medal of Valor at the end of the First Balkan War, in May 1913.[9] At the end of the Second Balkan War, during which he mainly led operations along the Albanian border, he was given the rank of second lieutenant as the top soldier in his class, ranked sixth at the Serbian military academy.[9] He served in World War I and was involved in the Serbian Army's retreat through Albania in 1915. He later received several decorations for his achievements on the Salonika Front. Following the war, he became a member of the Royal Guard of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes but had to leave his position in 1920 after taking part in a public argument between communist and nationalist sympathizers. He was subsequently stationed to Skopje. In 1921, he was admitted to the Superior Military Academy of Belgrade. In 1923, having finished his studies, he was promoted as an assistant to the military staff, along with the fifteen other best alumni of his promotion.[10] He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1930. That same year, he spent three months in Paris, following classes at the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr. Some authors claim that he met and befriended Charles de Gaulle during his stay, although there is no known evidence of this.[11] In 1935, he became a military attaché to the Kingdom of Bulgaria and was stationed to Sofia. On 6 September 1935, he was promoted to the rank of colonel. Mihailović then came in contact with members of Zveno and considered taking part in a plot which aimed to provoke Boris III's abdication and the creation of an alliance between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, but, being untrained as a spy, he was soon identified by Bulgarian authorities and was asked to leave the country. He was then appointed as an attaché to Czechoslovakia in Prague.[12]

His military career almost came to an abrupt end in 1939, when he submitted a report strongly criticizing the organization of the Royal Yugoslav Army (Serbo-Croatian: Vojska Kraljevine Jugoslavije, VKJ). Among his most important proposals were abandoning the defence of the northern frontier to concentrate forces in the mountainous interior; re-organizing the armed forces into Serb, Croat, and Slovene units in order to better counter subversive activities; and using mobile Chetnik units along the borders. Milan Nedić, the Minister of the Army, was incensed by Mihailović's report and ordered that he be confined to barracks for 30 days.[13] Afterwards, Mihailović became a professor at Belgrade's staff college.[14] In the summer of 1940, he attended a function put on by the British military attaché for the Association of Yugoslav Reserve NCOs. The meeting was seen as highly anti-Nazi in tone, and the German ambassador protested Mihailović's presence. Nedić once more ordered him confined to barracks for 30 days as well as demoted and placed on the retired list. These last punishments were avoided only by Nedić's retirement in November and his replacement by Petar Pešić.[13]

In the years preceding the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia, Mihailović was stationed in Celje, Drava Banovina (modern Slovenia). At the time of the invasion, Colonel Mihailović was an assistant to the chief-of-staff of the Yugoslav Second Army in northern Bosnia. He briefly served as the Second Army chief-of-staff[15] prior to taking command of a "Rapid Unit" (brzi odred) shortly before the Yugoslav High Command capitulated to the Germans on 17 April 1941.[16]

World War II

Following the invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia by Germany, Italy, Hungary, a small group of officers and soldiers led by Mihailović escaped in the hope of finding VKJ units still fighting in the mountains. After skirmishing with several Ustaše and Muslim bands and attempting to sabotage several objects, Mihailović and about 80 of his men crossed the Drina River into German-occupied Serbia[b] on 29 April.[17] Mihailović planned to establish an underground intelligence movement and establish contact with the Allies, though it is unclear if he initially envisioned to start an actual armed resistance movement.[18]

Formation of the Chetniks

The Chetnik flag. The flag reads: "For King and Fatherland – Liberty or Death".

For the time being, Mihailović established a small nucleus of officers with an armed guard, which he called the "Command of Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army".[18] After arriving at Ravna Gora in early May 1941, he realized that his group of seven officers and twenty four non-commissioned officers and soldiers was the only one.[19] He began to draw up lists of conscripts and reservists for possible use. His men at Ravna Gora were joined by a group of civilians, mainly intellectuals from the Serbian Cultural Club, who took charge of the movement's propaganda sector.[18]

The Chetniks of Kosta Pećanac, which were already in existence before the invasion, did not share Mihailović's desire for resistance.[20] In order to distinguish his Chetniks from other groups calling themselves Chetniks, Mihailović and his followers identified themselves as the "Ravna Gora movement".[20] The stated goal of the Ravna Gora movement was the liberation of the country from the occupying armies of Germany, Italy and the Ustaše, and the Independent State of Croatia (Serbo-Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH).[21]

Mihailović spent most of 1941 consolidating scattered VKJ remnants and finding new recruits. In August, he set up a civilian advisory body, the Central National Committee, composed of Serb political leaders including some with strong nationalist views such as Dragiša Vasić and Stevan Moljević.[21] On 19 June, a clandestine Chetnik courier reached Istanbul, whence royalist Yugoslavs reported that Mihailović appeared to be organizing a resistance movement against Axis forces.[22] Mihailović first established radio contact with the British in September 1941, when his radio operator raised a ship in the Mediterranean. On 13 September, Mihailović's first radio message to King Peter's government-in-exile announced that he was organizing VKJ remnants to fight against the Axis powers.[22]

Mihailović also received help from officers in other areas of Yugoslavia, such as Slovene officer Rudolf Perinhek, who brought reports on the situation in Montenegro. Mihailović sent him back to Montenegro with written authorization to organize units there, with the oral approval of officers such as Đorđije Lašić, Pavle Đurišić, Dimitrije Ljotić and Kosta Mušicki. Mihailović only gave vague and contradictory orders to Perinhek, mentioning the need to put off civil strife and to "remove enemies".[23]

Mihailović's strategy was to avoid direct conflict with the Axis forces, intending to rise up after Allied forces arrived in Yugoslavia.[24] Mihailović's Chetniks had had defensive encounters with the Germans, but reprisals and the tales of the massacres in the NDH made them reluctant to engage directly in armed struggle, except against the Ustaše in Serbian border areas.[25] In the meantime, following the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ), led by Josip Broz Tito, also went into action and called for a popular insurrection against the Axis powers in July 1941. Tito subsequently set up a communist resistance movement known as the Yugoslav Partisans.[26] By the end of August, Mihailović's Chetniks and the Partisans began attacking Axis forces, sometimes jointly despite their mutual diffidence, and captured numerous prisoners.[27] But Mihailović discouraged sabotage due to German reprisals (such as more than 3,000 killed in Kraljevo and Kragujevac) unless some great gain could be accomplished. Instead, he favored sabotage that could not easily be traced back to the Chetniks.[28] His reluctance to engage in more active resistance meant that most sabotage carried out in the early period of the war were due to efforts by the Partisans, and Mihailović lost several commanders and a number of followers who wished to fight the Germans to the Partisan movement.[29]

Even though Mihailović initially asked for discreet support, propaganda from the British and from the Yugoslav government-in-exile quickly began to exalt his feats. The creation of a resistance movement in occupied Europe was received as a morale booster. On 15 November, the BBC announced that Mihailović was the commander of the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland, which became the official name of Mihailović's Chetniks.[30]

Conflicts with Axis troops and Partisans

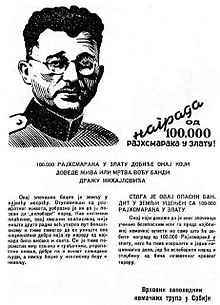

Nazi wanted poster for Colonel Mihailović from 9 December 1941

1942 German proclamation and reward offer for Mihailović, after the Chetnik killing of four German officers

Draža Mihailović as a small pet in the hands of the supposedly Jewish-controlled United States and United Kingdom as part of Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory , depicted in a poster from the Grand Anti-Masonic Exhibition

Mihailović soon realized that his men did not have the means to protect Serbian civilians against German reprisals.[31][32] The prospect of reprisals also fed Chetnik concerns regarding a possible takeover of Yugoslavia by the Partisans after the war, and they did not wish to engage in actions that might ultimately result in a post-war Serb minority.[33] Mihailović's strategy was to bring together the various Serb bands and build an organization capable of seizing power after the Axis withdrew or were defeated, rather than engaging in direct confrontation with them.[34] In contrast to the reluctance of Chetnik leaders to directly engage the Axis forces, the Partisans advocated open resistance, which appealed to those Chetniks desiring to fight the occupation.[35] By September 1941, Mihailović began losing men to the Partisans, such as Vlado Zečević (a priest), Lieutenant Ratko Martinović, and the Cer Chetniks led by Captain Dragoslav Račić[35][36]

On 19 September 1941, Tito met with Mihailović to negotiate an alliance between the Partisans and Chetniks, but they failed to reach an agreement as the disparity of the aims of their respective movements was great enough to preclude any real compromise.[37] Tito was in favour of a joint full-scale offensive, while Mihailović considered a general uprising to be premature and dangerous, as he thought it would trigger reprisals.[31] For his part, Tito's goal was to prevent an assault from the rear by the Chetniks, as he was convinced that Mihailović was playing a "double game", maintaining contacts with German forces via the Nedić government. Mihailović was in contact with Nedić's government, receiving monetary aid via Colonel Popović.[38] On the other hand, Mihailović sought to prevent Tito from assuming the leadership role in the resistance,[37][39] as Tito's goals were counter to his goals of the restoration of the Karađorđević dynasty and the establishment of Greater Serbia.[40] Further talks were scheduled for 16 October.[39]

At the end of September, the Germans launched a massive offensive against both Partisans and Chetniks called Operation Užice.[31] A joint British-Yugoslav intelligence mission, quickly assembled by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and led by Captain D. T. Hudson, arrived on the Montenegrin coast on 22 September, whence they had made their way with the help of Montenegrin Partisans to their headquarters, and then on to Tito's headquarters at Užice,[41] arriving on or around 25 October.[42] Hudson reported that earlier promises of supplies made by the British to Mihailović contributed to the poor relationship between Mihailović and Tito, as Mihailović correctly believed that no one outside of Yugoslavia knew about the Partisan movement,[43][44][45] and felt that "the time was ripe for drastic action against the communists".[43]

Tito and Mihailović met again on 27 October 1941 in the town of Brajići near Ravna Gora in an attempt to achieve an understanding, but found consensus only on secondary issues.[46] Immediately following the meeting, Mihailović began preparations for an attack on the Partisans, delaying the attack only for lack of arms.[47] Mihailović reported to the Yugoslav government-in-exile that he believed the occupation of Užice, the location of a gun factory, was required to prevent the strengthening of the Partisans.[44] On 28 October, two Chetnik liaison officers first approached Nedić and later that day German officer Josef Matl of the Armed Forces Liaison Office, and offered Mihailović's services in the struggle against the Partisans in exchange for weapons.[32][47] This offer was relayed to the German general in charge of the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, and a meeting was proposed by the German for 3 November. On 1 November, the Chetniks attacked the Partisan headquarters at Užice, but were beaten back.[48][49] On 3 November 1941 Mihailović postponed the proposed meeting with the German officers until 11 November, citing the "general conflict" in which the Chetniks and Partisans were engaged requiring his presence at his headquarters.[49][50] The meeting, organized through one of Mihailović's representatives in Belgrade, took place between the Chetnik leader and an Abwehr official, although it remains controversial if the initiative came from the Germans, from Mihailović himself, or from his liaison officer in Belgrade.[c] In the negotiations Mihailović assured the Germans that "it is not my intention to fight against the occupiers" and claimed that "I have never made a genuine agreement with the communists, for they do not care about the people. They are led by foreigners who are not Serbs: the Bulgarian Janković, the Jew Lindmajer, the Magyar Borota, two Muslims whose names I do not know and the Ustasha Major Boganić. That is all I know of the communist leadership."[51] It appears that Mihailović offered to cease activities in the towns and along the major communication lines, but ultimately no agreement was reached at the time due to German demands for the complete surrender of the Chetniks,[52][53][54] and the German belief that the Chetniks were likely to attack them despite Mihailović's offer.[55] After the negotiations, an attempt was made by the Germans to arrest Mihailović.[56] Mihailović carefully kept the negotiations with the Germans secret from the Yugoslav government-in-exile, as well as from the British and their representative Hudson.[52][48]

Mihailović's assault on the Partisan headquarters at Užice and Požega failed, and the Partisans mounted a rapid counterattack.[47][57] Within two weeks, the Partisans repelled Chetnik advances and surrounded Mihailović's headquarters at Ravna Gora. Having lost troops in clashes with the Germans,[58] sustained the loss of approximately 1,000 troops and considerable equipment at the hands of the Partisans,[59] received only one small delivery of arms from the British in early November,[60] and been unsuccessful in convincing the Germans to provide him with supplies,[49] Mihailović found himself in a desperate situation.[59][61]

In mid-November, the Germans launched an offensive against the Partisans, Operation Western Morava, which bypassed Chetnik forces.[57][62][63] Having been unable to quickly overcome the Chetniks, faced with reports that the British considered Mihailović as the leader of the resistance, and under pressure from the German offensive, Tito approached Mihailović with an offer to negotiate, which resulted in talks and later an armistice between the two groups on 20 or 21 November.[62][57][64] Tito and Mihailović had one last phone conversation on 28 November, in which Tito announced that he would defend his positions, while Mihailović said that he would disperse.[31][53][63] On 30 November, Mihailović's unit leaders decided to join the "legalized" Chetniks under General Nedić's command, in order to be able to continue the fight against the Partisans without the possibility of being attacked by the Germans and to avoid compromising Mihailović's relationship with the British. Evidence suggests that Mihailović did not order this, but rather only sanctioned the decision.[55][65] About 2,000–3,000 of Mihailović's men actually enlisted in this capacity within the Nedić regime. The legalization allowed his men to have a salary and an alibi provided by the collaborationist administration, while it provided the Nedić regime with more men to fight the communists, although they were under the control of the Germans.[66] Mihailović also considered that he could, using this method, infiltrate the Nedić administration, which was soon fraught with Chetnik sympathizers.[67] While this arrangement differed from the all-out collaboration of Kosta Pećanac, it caused much confusion over who and what the Chetniks were.[68] Some of Mihailović's men crossed into Bosnia to fight the Ustaše while most abandoned the struggle.[68] Throughout November, Mihailović's forces had been under pressure from German forces, and on 3 December, the Germans issued orders for Operation Mihailovic, an attack against his forces in Ravna Gora.[63] On 5 December, the day before the operation, Mihailović was warned by contacts serving under Nedić of the impending attack,[63] likely by Milan Aćimović.[69] He closed down his radio transmitter on that day to avoid giving the Germans hints of his whereabouts[70] and then dispersed his command and the remainder of his forces.[63] The remnants of his Chetniks retreated to the hills of Ravna Gora, but were under German attack throughout December.[71] Mihailović narrowly avoided capture.[72] On 10 December, a bounty was put on his head by the Germans.[56] In the meantime, on 7 December, the BBC announced his promotion to the rank of brigade general.[73]

Activities in Montenegro and the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia

Mihailović did not resume radio transmissions with the Allies before January 1942. In early 1942, the Yugoslav government-in-exile reorganized and appointed Slobodan Jovanović as prime minister, and the cabinet declared the strengthening of Mihailović's position as one of its primary goals. It also unsuccessfully sought to obtain support from both the Americans and the British.[74] On 11 January, Mihailović was named "Minister of the Army, Navy and Air Forces" by the government-in-exile.[75] The British had suspended support in late 1941 following Hudson's reports of the conflict between the Chetniks and Partisans. Mihailović, infuriated by Hudson's recommendations, denied Hudson radio access and had no contact with him through the first months of 1942.[76] Although Mihailović was in hiding, by March the Nedić government located him, and a meeting sanctioned by the German occupation took place between him and Aćimović. According to historian Jozo Tomasevich, following this meeting, General Bader was informed that Mihailović was willing to put himself at the disposal of the Nedić government in the fight against the communists, but Bader refused his offer.[72] In April 1942, Mihailović, still hiding in Serbia, resumed contact with British envoy Hudson, who was also able to resume his radio transmission to Allied headquarters in Cairo, using Mihailović's transmitter. In May, the British resumed sending assistance to the Chetniks, although only to a small extent,[77] with a single airdrop on 30 March.[78] Mihailović subsequently left for Montenegro, arriving there on 1 June.[79] He established his headquarters there and on 10 June was formally appointed as Chief-of-Staff of the Supreme Command of the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland.[80] A week later he was promoted to the rank of General of the Army.[1] The Partisans, in the meantime, insisted to the Soviets that Mihailović was a traitor and a collaborator, and should be condemned as such. The Soviets initially saw no need for it, and their propaganda kept supporting Mihailović. Eventually, on 6 July 1942, the station Radio Free Yugoslavia, located in the Comintern building in Moscow, broadcast a resolution from Yugoslav "patriots" in Montenegro and Bosnia labeling Mihailović a collaborator.[81]

Mihailović confers with his men

In Montenegro, Mihailović found a complex situation. The local Chetnik leaders, Stanišić and Đurišić, had reached arrangements with the Italians and were cooperating with them against the communist-led Partisans.[82][83] Mihailović later claimed at his trial in 1946 that he was unaware of these arrangements prior to his arrival in Montenegro, and had to accept them once he arrived,[84][85] as Stanišić and Đurišić acknowledged him as their leader in name only and would only follow Mihailović's orders if they supported their interests.[85] Mihailović believed that Italian military intelligence was better informed than he was of the activities of his commanders.[85] He tried to make the best of the situation, and accepted the appointment of Blažo Đukanović as the figurehead commander of "nationalist forces" in Montenegro. While Mihailović approved the destruction of communist forces, he aimed to exploit the connections of Chetniks commanders with the Italians to get food, arms and ammunition in the expectation of an Allied landing in the Balkans. On 1 December, Đurišić organised a Chetnik "youth conference" at Šahovići. The congress, which historian Stevan K. Pavlowitch writes expressed "extremism and intolerance", nationalist claims were made on parts of Albania, Bulgaria, Romania and Italy, while its resolutions posited the restoration of a monarchy with a period of transitional Chetnik dictatorship. Mihailović and Đukanović did not attend the event, which was entirely dominated by Đurišić, but they sent representatives.[86] In the same month Mihailović informed his subordinates that: "The units of the Partisans are filled with thugs of the most varied kinds, such as Ustašas – the worst butchers of the Serb people – Jews, Croats, Dalmatians, Bulgarians, Turks, Magyars, and all the other nations of the world."[87]

In the NDH, Ilija Trifunović-Birčanin, a leader of pre-war Chetnik organizations, commanded the Chetniks in Dalmatia, Lika, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He led the "nationalist" resistance against Partisans and Ustaše and acknowledged Mihailović as formal leader, but acted on his own, with his troops being used by the Italians as the local Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia (MVAC). Italian commander Mario Roatta aimed to spare Italian lives, but also to counter the Ustaše and Germans, to undermine Mihailović's authority among the Chetniks by playing up local leaders, and to have possible links with Mihailović and the Allies in case the Axis lost the war.[citation needed] Chetniks, led by Dobroslav Jevđević, came from Montenegro to help the Bosnian Serb population against the Ustaše. They murdered and pillaged in Foča until the Italians intervened in August. The Chetniks also asked the Italians for protection against Ustaše retribution. On 22 July, Mihailović met with Trifunović-Birčanin, Jevđević, and his newly appointed delegate in Herzegovina, Petar Baćović. The meeting was supposedly secret, but was known to Italian intelligence. Mihailović gave no precise orders but expressed his confidence in both his subordinates, adding, according to Italian reports, that he was waiting for help from the Allies to start a real guerrilla campaign, in order to spare Serb lives. Summoned by Roatta upon their return, Trifunović-Birčanin and Jevđević assured the Italian commander that Mihailović was merely a "moral head" and that they would not attack Italians, even if he should give such an order.[88]

Having become more and more concerned with domestic enemies and concerned that he be in a position to control Yugoslavia after the Allies defeated the Axis, Mihailović concentrated from Montenegro on directing operations, in the various parts of Yugoslavia, mostly against Partisans, but also against the Ustaše and Dimitrije Ljotić's Serbian Volunteer Corps (SDK).[80] During the autumn of 1942, Mihailović's Chetniks—at the request of the British organization—sabotaged several railway lines used to supply Axis forces in the Western Desert of northern Africa.[89] In September and December, Mihailović's actions damaged the railway system seriously; the Allies gave him credit for inconveniencing Axis forces and contributing to Allied successes in Africa.[90] The credit given to Mihailović for sabotages was maybe undeserved:

But an S.O.E. 'appreciation on Jugoslavia' of mid-November said: "... So far no telegrams have been received from either of our liaison officers reporting any sabotage undertaken by General Mihajlović, nor have we received any reports of fighting against the Axis troops." In Yugoslavia, therefore, S.O.E. could claim no equivalent to the Gorgopotamos operation in Greece. From all this it might seem that since the autumn of 1941 the British had – wittingly or unwittingly – been co-operating in a gigantic hoax.[91]

Early in September 1942, Mihailović called for civil disobedience against the Nedić regime through leaflets and clandestine radio transmitters. This prompted fighting between the Chetniks and followers of the Nedić regime. The Germans, whom the Nedić administration had called for help against Mihailović, responded to Nedić's request and to the sabotages with mass terror, and attacked the Chetniks in late 1942 and early 1943. Roberts mentions Nedić's request for help as the main reason for German action, and does not mention the sabotage campaign.[80] Pavlowitch, on the other hand, mentions the sabotages as being conducted simultaneously with the propaganda actions. Thousands of arrests were made and it has been estimated that during December 1942, 1,600 Chetnik combatants were killed by the Germans through combat actions and executions. These actions by the Nedić regime and the Germans "brought to an abrupt conclusion much of the anti-German action Mihailović had started up again since the summer (of 1942)".[92]

Mihailović had great difficulties controlling his local commanders, who often did not have radio contacts and relied on couriers to communicate. He was, however, apparently aware that many Chetnik groups were committing crimes against civilians and acts of ethnic cleansing; according to Pavlowitch, Đurišić proudly reported to Mihailović that he had destroyed Muslim villages, in retribution against acts committed by Muslim militias. While Mihailović apparently did not order such acts himself, and disapproved of them, he also failed to take any action against them, being dependent on various armed groups whose policy he could neither denounce nor condone. He also hid the situation from the British and the Yugoslav government-in-exile.[93] Many terror acts were committed by Chetnik groups against their various enemies, real or perceived, reaching a peak between October 1942 and February 1943.[94]

Terror tactics and cleansing actions

Chetnik ideology encompassed the notion of Greater Serbia, to be achieved by forcing population shifts in order to create ethnically homogeneous areas.[95] Partly due to this ideology and partly in response to violent actions undertaken by the Ustaše and the Muslim forces attached to them,[96] Chetniks forces engaged in numerous acts of violence including massacres and destruction of property, and used terror tactics to drive out non-Serb groups.[97] In the spring of 1942, Mihailović penned in his diary: "The Muslim population has through its behaviour arrived at the situation where our people no longer wish to have them in our midst. It is necessary already now to prepare their exodus to Turkey or anywhere else outside our borders."[98]

"Instrukcije" ("Instructions") of 1941 attributed to Mihailović ordering the cleansing of non-Serbs from territories claimed by the Chetniks as part of a Greater Serbia

| Serbian Wikisource has original text related to this article: Instrukcija D. Mihailovića Pavlu Đurišiću od 20.12.1941. |

Mihailović's role in such actions is unclear as there is "... no definite evidence that [he] himself ever called for ethnic cleansing".[99] Instructions to his Montenegrin subordinates commanders, Major Lašić and Captain Pavle Đurišić, which prescribe cleansing actions of non-Serb elements in order to create Greater Serbia have been attributed to Mihailović by some historians,[100][101][102][103] but some historians argue that the document was a forgery made by Đurišić after he failed to reach Mihailović in December 1941 after the latter was driven out of Ravna Gora by German forces.[99][104][105] It is important to note that if the document is a forgery, it was forged by Chetniks hoping it would be taken as a legitimate order, not by their opponents seeking to discredit the Chetniks.[99] The objectives outlined in the directive were:[106]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

- The struggle for the liberty of our whole nation under the scepter of His Majesty, King Peter II;

- the creation of a Great Yugoslavia and within it of a Great Serbia, which is to be ethnically pure and is to include Serbia [meaning also Vardar Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Srijem, the Banat, and Bačka];

- the struggle for the inclusion into Yugoslavia of all still unliberated Slovene territories under the Italians and Germans (Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, and Carinthia) as well as Bulgaria, and northern Albania with Scutari;

- the cleansing of the state territory of all national minorities and a-national elements [i.e. the Partisans and their supporters];

- the creation of contiguous frontiers between Serbia and Montenegro, as well as between Serbia and Slovenia by cleansing the Muslim population from Sandžak and the Muslim and Croat populations from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Whether or not the instructions were forged, Mihailović was certainly aware of both the ideological goal of cleansing and of the violent acts taken to accomplish that goal. Stevan Moljević worked out the basics of the Chetnik program while at Ravna Gora in the summer of 1941,[107] and Mihailović sent representatives to the Conference of Young Chetnik Intellectuals of Montenegro where the basic formulations were expanded.[108] Đurišić played the dominant role at this conference. Relations between Đurišić and Mihailović were strained, and although Mihailović did not participate, neither did he take any action to counter it.[109] In 1943, Đurišić followed Chetnik Supreme Command orders to carry out "cleansing actions" against Muslims and reported the thousands of old men, women and children he massacred to Mihailović.[110] Mihailović was either "unable or unwilling to stop the massacres".[111] In 1946, Mihailović was indicted, amongst other things, of having "given orders to his commanders to destroy the Muslims (whom he called Turks) and the Croats (whom he called Ustashas)."[112] At his trial Mihailović claimed that he never ordered the destruction of Croat and Muslim villages and that some of his subordinates hid such activities from him.[113] He was later convicted of crimes that included having "incited national and religious hatred and discord among the peoples of Yugoslavia, as a consequence of which his Chetnik bands carried out mass massacres of the Croat and Muslim as well as of the Serb population that did not accept the occupation."[112]

Relations with the British

Winston Churchill became increasingly doubtful about Mihailović.

.mw-parser-output .quoteboxbackground-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%;max-width:100%.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleftmargin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatrightmargin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centeredmargin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright pfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .quotebox-titlebackground-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:beforefont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:afterfont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-alignedtext-align:left.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-alignedtext-align:right.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-alignedtext-align:center.mw-parser-output .quotebox citedisplay:block;font-style:normal@media screen and (max-width:360px).mw-parser-output .quoteboxmin-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important

Basil Davidson, member of the British mission

On 15 November 1942, Captain Hudson cabled to Cairo that the situation was problematic, that opportunities for large-scale sabotage were not exploited because of Mihailović's willingness to avoid reprisals and that, while waiting for an Allied landing and victory, the Chetnik leader might come to "any sound understanding with either Italians or Germans which he believed might serve his purposes without compromising him", in order to defeat the communists.[115] In December, Major Peter Boughey, a member of SOE's London staff, insisted to Živan Knežević, a member of the Yugoslav cabinet, that Mihailović was a quisling, who was openly collaborating with the Italians.[116] The Foreign Office called Boughey's declarations "blundering" but the British were worried about the situation and Mihailović's inactivity.[117] A British senior officer, Colonel S. W. Bailey, was then sent to Mihailović and was parachuted into Montenegro on Christmas Day. His mission was to gather information and to see if Mihailović had carried out necessary sabotages against railroads.[115] During the following months, the British concentrated on having Mihailović stop Chetnik collaboration with Axis forces and perform the expected actions against the occupiers, but they were not successful.[118]

In January 1943, the SOE reported to Churchill that Mihailović's subordinate commanders had made local arrangements with Italian authorities, although there was no evidence that Mihailović himself had ever dealt with the Germans. The report concluded that, while aid to Mihailović was as necessary as ever, it would be advisable to extend assistance to other resistance groups and to try to reunite the Chetniks and the Partisans.[119] British liaison officers reported in February that Mihailović had "at no time" been in touch with the Germans, but that his forces had been in some instances aiding the Italians against the Partisans (the report was simultaneous with Operation Trio). Bailey reported that Mihailović was increasingly dissatisfied with the insufficient help he was receiving from the British.[120] Mihailović's movement had been so inflated by British propaganda that the liaison officers found the reality decidedly below expectations.[121]

On 3 January 1943, just before Case White, an Axis conference was held in Rome, attended by German commander Alexander Löhr, NDH representatives, and by Jevđević who, this time, collaborated openly with the Axis forces against the Partisans, and had gone to the conference without Mihailović's knowledge. Mihailović disapproved of Jevđević's presence and reportedly sent him an angry message, but his actions were limited to announcing that Jevđević's military award would be withdrawn.[122]

On 28 February 1943, in Bailey's presence, Mihailović addressed his troops in Lipovo. Bailey reported that Mihailović had expressed his bitterness over "perfidious Albion" who expected the Serbs to fight to the last drop of blood without giving them any means to do so, had said that the Serbs were completely friendless, that the British were holding King Peter II and his government as virtual prisoners, and that he would keep accepting help from the Italians as long as it would give him the means to annihilate the Partisans. Also according to Bailey's report, he added that his enemies were the Ustaše, the Partisans, the Croats and the Muslims and that only after dealing with them would he turn to the Germans and the Italians.[123][124]

While defenders of Mihailović have argued that Bailey had mistranslated the speech,[d] and may have even done so intentionally,[125] the effect on the British was disastrous and marked the beginning of the end for British-Chetnik cooperation. The British officially protested to the Yugoslav government-in-exile and demanded explanations regarding Mihailović's attitude and collaboration with the Italians. Mihailović answered to his government that he had had no meetings with Italian generals and that Jevđević had no command to do so. The British announced that they would send him more abundant supplies.[126] Also in early 1943, the tone of the BBC broadcasts became more and more favorable to the Partisans, describing them as the only resistance movement in Yugoslavia, and occasionally attributing to them resistance acts actually undertaken by the Chetniks.[127] Bailey complained to the Foreign Office that his position with Mihailović was being prejudiced by this.[128] The Foreign Office protested and the BBC apologized, but the line did not really change.[128]

George Orwell, The Freedom of the Press (1945)

Defeat in the battle of the Neretva

During Case White, the Italians heavily supported the Chetniks in the hope that they would deal a fatal blow to the Partisans. The Germans disapproved of this collaboration, about which Hitler personally wrote to Mussolini.[130] At the end of February, shortly after his speech, Mihailović himself joined his troops in Herzegovina near the Neretva in order to try to salvage the situation. The Partisans nevertheless defeated the opposing Chetniks troops, who were in a state of disarray, and managed to go across the Neretva.[131] In March, the Partisans negotiated a truce with Axis forces in order to gain some time and use it to defeat the Chetniks. While Ribbentrop and Hitler finally overruled the orders of their subordinates and forbade any such contacts, the Partisans benefited from this brief truce, during which Italian support for the Chetniks was suspended, and which allowed Tito's forces to deal a severe blow to Mihailović's troops.[132]

In May, the German intelligence service also tried to establish a contact with Mihailović to see if an alliance against the Partisans was possible. In Kolašin, they met with a Chetnik officer, who did not introduce himself. They assumed they had met the general himself, but the man was possibly not Mihailović, whom Bailey reported to be in another area at the same period. The German command, however, reacted strongly against any attempt at "negotiating with the enemy".[133]

The Germans then turned to their next operation, code-named Schwarz, and attacked the Montenegrin Chetniks. Đurišić appears to have suggested to Mihailović a short-term cooperation with the Germans against the Partisans, something Mihailović refused to condone. Đurišić ended up defending his headquarters at Kolašin against the Partisans. On 14 May, the Germans entered Kolašin and captured Đurišić, while Mihailović escaped.[132][134]

In late May, after regaining control of most of Montenegro, the Italians turned their efforts against the Chetniks, at least against Mihailović's forces, and put a reward of half-a-million lire for the capture of Mihailović, and one million for the capture of Tito.[135]

Allied support shifts

In April and May 1943, the British sent a mission to the Partisans and strengthened their mission to the Chetniks. Major Jasper Rootham, one of the liaison officers to the Chetniks, reported that engagements between Chetniks and Germans did occur, but were invariably started by German attacks. During the summer, the British sent supplies to both Chetniks and Partisans.[136]

Mihailović returned to Serbia and his movement rapidly recovered its dominance in the region. Receiving more weapons from the British, he undertook a series of actions and sabotages, disarmed Serbian State Guard (SDS) detachments and skirmished with Bulgarian troops, though he generally avoided the Germans, considering that his troops were not yet strong enough. In Serbia, his organization controlled the mountains where Axis forces were absent. The collaborationist Nedić administration was largely infiltrated by Mihailović's men and many SDS troops being actually sympathetic to his movement. After his defeat in Case White, Mihailović tried to improve his organization. Dragiša Vasić, the movement's ideologue who had opposed the Italian connection and clashed with Mihailović, left the supreme command. Mihailović tried to extend his contacts to Croats and traditional parties, and to revitalise his contacts in Slovenia.[137] The United States sent liaison officers to join Bailey's mission with Mihailović, while also sending men to Tito.[138] The Germans, in the meantime, became worried by the growing strength of the Partisans and made local arrangements with Chetnik groups, though not with Mihailović himself. According to Walter R. Roberts, there is "little doubt" that Mihailović was aware of these arrangements and that he might have regarded them as the lesser of two evils, his primary aim being to defeat the Partisans.[139]

From the beginning of 1943, British impatience with Mihailović grew. From the decrypts of German wireless messages, Churchill and his government concluded that the Chetniks' collaboration with the Italians went beyond what was acceptable and that the Partisans were doing the most severe damage to the Axis.[140]

German warrant for Mihailović offering a reward of 100,000 gold marks for his capture, dead or alive, 1943

With Italy's withdrawal from the war in September 1943, the Chetniks in Montenegro found themselves under attack by both the Germans and the Partisans, who took control of large parts of Montenegrin territory, including the former "Chetnik capital" of Kolašin. Đurišić, having escaped from a German camp in Galicia, found his way to Yugoslavia, was captured again, and was then asked by collaborationist prime minister Milan Nedić to form a Montenegrin Volunteer Corps against the Partisans. He was pledged to Nedić, but also made a secret allegiance to Mihailović. Both Mihailović and Đurišić expected a landing by the Western Allies. In Serbia, Mihailović was considered the representative of the victorious Allies.[141] In the chaotic situation created by the Italian surrender, several Chetnik leaders overtly collaborated with the Germans against the reinforced Partisans; approached by an Abwehr agent, Jevđević offered the services of about 5,000 men. Momčilo Đujić also went to the Germans for cover against the Ustaše and Partisans, although he was distrusted.[142] In October 1943, Mihailović, at the Allies' request, agreed to undertake two sabotage operations, which had the effect of making him even more of a wanted man and forced him, according to British reports, to change his headquarters frequently.[143]

By November and December 1943, the Germans had realized that Tito was their most dangerous opponent; German representative Hermann Neubacher managed to conclude secret arrangements with four of Mihailović's commanders for the cessation of hostilities for periods of five to ten weeks. The Germans interpreted this as a sign of weakness from the Mihailović movement. The truces were kept secret, but came to the knowledge of the British through decrypts. There is no evidence that Mihailović had been involved or approved, though British Military Intelligence found it possible that he was "conniving".[144] At the end of October the local signals decrypted in Cairo had disclosed that Mihailović had ordered all Chetnik units to co-operate with Germany against the Partisans.[145] This order for cooperation was originally decrypted by Germans, and it was noted in the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht War Journal.[146][e]

The British were more and more concerned about the fact that the Chetniks were more willing to fight Partisans than Axis troops. At the third Moscow Conference in October 1943, Anthony Eden expressed impatience about Mihailović's lack of action.[147] The report of Fitzroy Maclean, liaison officer to the Partisans, convinced Churchill that Tito's forces were the most reliable resistance group. The report of Charles Armstrong, liaison officer to Mihailović, arrived too late for Anthony Eden to take it to the Tehran Conference in late November 1943, though Stevan K. Pavlowitch thinks that it would probably been insufficient to change Churchill's mind. At Tehran, Churchill argued in favor of the Partisans, while Joseph Stalin expressed limited interest but agreed that they should receive the greatest possible support.[148]

On 10 December, Churchill met King Peter II in London and told him that he possessed irrefutable proofs of Mihailović's collaboration with the enemy and that Mihailović should be eliminated from the Yugoslav cabinet. Also in early December, Mihailović was asked to undertake an important sabotage mission against railways, which was later interpreted as a "final opportunity" to redeem himself. However, possibly not realizing how Allied policy had evolved, he failed to give the go-ahead.[149] On 12 January 1944, the SOE in Cairo sent a report to the Foreign Office, saying that Mihailović's commanders had collaborated with Germans and Italians, and that Mihailović himself had condoned and in certain cases approved their actions. This hastened the British's decision to withdraw their thirty liaison officers to Mihailović.[150] The mission was effectively withdrawn in the spring of 1944. In April, one month before leaving, liaison officer Armstrong noted that Mihailović had been mostly active in propaganda against the Axis, that he had missed numerous occasions for sabotage in the last six or eight months and that the efforts of many Chetnik leaders to follow Mihailović's orders for inactivity had evolved into non-aggression pacts with Axis troops, although the mission had no evidence of collaboration with the enemy.[151]

In the meantime, Mihailović tried to improve the organization of his movement. On 25 January 1944, with the help of Živko Topalović, he organized in Ba, a village near Ravna Gora, a Chetnik meeting also meant to remove the shadow of the previous congress held in Montenegro. The congress was attended by 274 people, representing various parties, and aimed to be a reaction against the arbitrary behaviour of some commanders. The organization of a new, democratic, possibly federal, Yugoslavia, was mentioned, though the proposals remained vague, and an appeal was even made for the KPJ to join. The Chetnik command structure was formally reorganized. Đurišić was still in charge of Montenegro and Đujić of Dalmatia, but Jevđević was excluded. The Germans and Bulgarians reacted to the congress by conducting an operation against the Chetniks in northern Serbia in February, killing 80 and capturing 913.[152]

After May and the withdrawal of the British mission, Mihailović kept transmitting radio messages to the Allies and to his government, but no longer received replies.

In July and August 1944, Mihailović ordered his forces to cooperate with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and 60th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS) in the successful rescue of hundreds downed Allied airmen between August and December 1944 in what was called Operation Halyard;[153][154] for this, he was posthumously awarded the Legion of Merit by United States President Harry S. Truman. Details of this rescue mission are described in The Forgotten 500, by Gregory A. Freeman, published in 2007. [1]

According to historian Marko Attila Hoare, "On other occasions, however, Mihailović's Chetniks rescued German airmen and handed them over safely to the German armed forces ... The Americans, with a weaker intelligence presence in the Balkans than the British, were less in touch with the realities of the Yugoslav civil war. They were consequently less than enthusiastic about British abandonment of the anti-communist Mihailović, and more reserved toward the Partisans." Several Yugoslavs were also evacuated in Operation Halyard, along with Topalović; they tried to raise more support abroad for Mihailović's movement, but this came too late to reverse Allied policy.[155] The United States also sent an intelligence mission to Mihailović in March, but withdrew it after Churchill advised Roosevelt that all support should go to Tito and that "complete chaos" would ensue if the Americans also backed Mihailović.[153]

In July, Ivan Šubašić formed the new Yugoslav government-in-exile, which did not include Mihailović as minister. Mihailović, however, remained the official chief-of-staff of the Yugoslav Army. On 29 August, upon the recommendation of his government, King Peter dissolved by royal decree the Supreme Command, therefore abolishing Mihailović's post. On 12 September, King Peter broadcast a message from London, announcing the gist of 29 August's decree and calling upon all Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to "join the National Liberation Army under the leadership of Marshal Tito". He also proclaimed that he strongly condemned "the misuse of the name of the King and the authority of the Crown by which an attempt has been made to justify collaboration with the enemy". Though the King did not mention Mihailović, it was clear who he meant. According to his own account, Peter had obtained after strenuous talks with the British not to say a word directly against Mihailović. The message had a devastating effect on the morale of the Chetniks. Many men left Mihailović after the broadcast; others remained out of loyalty to him.[156]

Defeat in 1944–45

At the end of August 1944, the Soviet Union's Red Army arrived on the eastern borders of Yugoslavia. In early September, it invaded Bulgaria and coerced it into turning against the Axis. Mihailović's Chetniks, meanwhile, were so badly armed to resist the Partisan incursions into Serbia that some of Mihailović's officers, including Nikola Kalabić, Neško Nedić and Dragoslav Račić, met German officers on 11 August to arrange a meeting of Mihailović with Neubacher and to set forth the conditions for increased collaboration.[157] Nedić, in turn, apparently picked up the idea and suggested forming an army of united anti-communist forces; he arranged a secret meeting with Mihailović, which apparently took place around 20 August. From the existing accounts, they met in a dark room and Mihailović remained mostly silent, so much so that Nedić was not even sure afterwards that he had actually met the real Mihailović. According to British official Stephen Clissold, Mihailović was initially very reluctant to go to the meeting, but was finally convinced by Kalabić. It appears that Nedić offered to obtain arms from the Germans, and to place his Serbian State Guard under Mihailović's command, possibly as part of an attempt to switch sides as Germany was losing the war.[158] Neubacher favored the idea, but it was vetoed by Hitler, who saw this as an attempt to establish an "English fifth column" in Serbia. According to Pavlowitch, Mihailović, who was reportedly not enthusiastic about the proposal, and Nedić might have been trying to "exploit each other's predicaments", while Nedić may have considered letting Mihailović "take over". At the end of August, Mihailović also met an OSS mission, headed by Colonel Robert McDowell, who stayed with him until November.[159]

As the Red Army approached, Mihailović thought that the outcome of war would depend on Turkey entering the conflict, followed at last by an Allied incursion in the Balkans. He called upon all Yugoslavs to remain faithful to the King, and claimed that Peter had sent him a message telling him not to believe what he had heard on the radio about his dismissal. His troops started to break up outside Serbia in mid-August, as he tried to reach to Muslim and Croat leaders for a national uprising. However, whatever his intentions, he proved to have little attraction for non-Serbs. Đurišić, while leading his Montenegrin Volunteer Corps, which was related on paper to Ljotić's forces, accepted once again Mihailović's command.[160] Mihailović ordered a general mobilization on 1 September; his troops were engaged against the Germans and the Bulgarians, while also under attack by the Partisans.[156] On 4 September, Mihailović issued a circular telegram ordering his commanders that no action can be undertaken without his orders, save against the communists.[161] German sources confirm the loyalty of Mihailović and forces under his direct influence in this period.[f] The Partisans then penetrated Chetnik territory, fighting a difficult battle and ultimately defeating Mihailović's main force by October. On 6 September, what was left of Nedić's troops openly joined Mihailović. In the meantime, the Red Army encountered both the Partisans and Chetniks while entering from Romania and Bulgaria. They briefly cooperated with the Chetniks against retreating Germans, before disarming them. Mihailović sent a delegation to the Soviet command, but his representatives were ignored and ultimately arrested. Mihailović's movement collapsed in Serbia under the attacks of Soviets, Partisans, Bulgarians and fighting with the retreating Germans. Still hoping for a landing by the Western Allies, he headed for Bosnia with his staff, McDowell and a force of a few hundred. He set up a few Muslim units and appointed Croat Major Matija Parac as the head of an as yet non-existent Croatian Chetnik army. Nedić himself had fled to Austria. On 25 May 1945, he wrote to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, asserting that he had always been a secret ally of Mihailović.[162]

Now hoping for support from the United States, Mihailović met a small British mission between the Neretva river and Dubrovnik, but realized that it wasn't the signal of the hoped-for landing. McDowell was evacuated on 1 November and was instructed to offer Mihailović the opportunity to leave with him. Mihailović refused, as he wanted to remain until the expected change of Western Allied policy.[163] During the next weeks, the British government also raised the possibility of evacuating Mihailović by arranging a "rescue and honorable detention", and discussed the matter with the United States. In the end, no action was taken.[164] With their main forces in east Bosnia, the Chetniks under Mihailović's personal command in the late months of 1944 continued to collaborate with Germans. Colonel Borota and vojvoda Jevđević maintained contacts with Germans for the whole group.[165] In January 1945, Mihailović tried to regroup his forces on the Ozren heights, planning Muslim, Croatian and Slovenian units. His troops were, however, decimated and worn out, some selling their weapons and ammunition, or pillaging the local population. Đurišić joined Mihailović, with his own depleted forces, and found out that Mihailović had no plan.[166] Đurišić went his own way, and was killed on 12 April in a battle with the Ustaše.[167]

On 17 March 1945, Mihailović was visited in Bosnia by German emissary Stärker, who requested that Mihailović transmit to the Allied headquarters in Italy a secret German offer of capitulation. Mihailović transmitted the message, which was to be his last.[168] Ljotić and several independent Chetnik leaders in Istria proposed the forming of a common anti-communist front in the north-western coast, which could be acceptable to the Western Allies. Mihailović was not in favor of such a heterogeneous gathering, but did not reject Ljotić's proposal entirely, since the littoral area would be a convenient place to meet the Western Allies, and to join Slovene anti-communists, while Germany's collapse might make an anti-communist alliance possible. He authorized the departure of all who wanted to go, but few Chetniks ultimately arrived on the coast, with many being decimated on their way by Ustaše, Partisans, sickness and hunger.[169] On 13 April, Mihailović set out for northern Bosnia, on a 280 km-long march back to Serbia, aiming to start over a resistance movement, this time against the communists. His units were decimated by clashes with the Ustaše and Partisans, as well as dissension and typhus. On 10 May, they were attacked by Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), the successor to the Partisans. Mihailović managed to escape with 1,000–2,000 men, who gradually dispersed. Mihailović himself went into hiding in the mountains with a handful of men.[170]

Capture, trial and execution

Mihailović's trial

The Yugoslav authorities wanted to catch Mihailović alive in order to stage a full-scale trial.[171] He was finally caught on 13 March 1946.[172] The elaborate circumstances of his capture were kept secret for sixteen years. According to one existing version, Mihailović was approached by men who were supposedly British agents offering him help and an evacuation by airplane. After hesitating, he boarded the airplane, only to discover that it was a trap set up by the OZNA. Another version, proposed by the Yugoslav government, is that he was betrayed by Nikola Kalabić, who revealed his place of hiding in exchange for leniency.[173]

The trial of Draža Mihailović opened on 10 June 1946. His co-defendants were other prominent figures of the Chetnik movement as well as members of the Yugoslav government-in-exile, such as Slobodan Jovanović, who were tried in absentia, but also members of ZBOR and of the Nedić regime.[174] The main prosecutor was Miloš Minić, later Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Yugoslav government. The Allied airmen he had rescued in 1944 were not allowed to testify in his favor.[175] Mihailović evaded several questions by accusing some of his subordinates of incompetence and disregard of his orders. The trial shows, according to Jozo Tomasevich, that he had never firm and full control over his local commanders.[176] A Committee for the Fair Trial of General Mihailović was set up in the United States, but to no avail. Mihailović is quoted as saying, in his final statement, "I wanted much; I began much; but the gale of the world carried away me and my work.".[177]

Roberts considers that the trial was "anything but a model of justice" and that "it is clear that Mihailović was not guilty of all, or even many, of the charges brought against him" though Tito would probably not have had a fair trial either, had Mihailović prevailed. Mihailović was convicted of high treason and war crimes, and was executed on 17 July 1946.[172] He was executed together with nine other officers in Lisičiji Potok, about 200 meters from the former Royal Palace. His body was reportedly covered with lime and the position of his unmarked grave was kept secret.[178]

Rehabilitation

In March 2012, Vojislav Mihailović filed a request for his grandfather's rehabilitation in the high court.[179] The announcement caused a negative reaction in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia alike.[179]Željko Komšić, presidency member of Bosnia and Herzegovina, advocated the withdrawal of the Bosnian ambassador to Serbia if rehabilitation passes.[180] Former Croatian President Ivo Josipović stated that the attempted rehabilitation is harmful for Serbia and contrary to historical facts.[181] He elaborated that Mihailović "is a war criminal and Chetnikism is a quisling criminal movement".[181] Croatian foreign minister Vesna Pusić commented that the rehabilitation will only cause suffering to Serbia.[182] In Serbia, fourteen NGOs stated in an open letter that "the attempted rehabilitation of Draža Mihailović demeans the struggle of both the Serbians and all the other peoples of the former Yugoslavia against fascism".[179] Members of the Women in Black protested in front of the higher court.[183]

The High Court rehabilitated Draža Mihailović on 14 May 2015. This ruling reverses the judgment passed in 1946, sentencing Mihailović to death for collaboration with the occupying Nazi forces and stripping him of all his rights as a citizen. According to the ruling, the Communist regime staged a politically and ideologically motivated trial.[184][185]

Family

In 1920, Mihailović married Jelica Branković; they had three children. One of his sons, Branko Mihailović, was a communist sympathizer and later supported the Partisans.[186] His daughter, Gordana Mihailović, also sided with the Partisans. She spent most of the war in Belgrade and, after the Partisans took the city, spoke on the radio to denounce her father as a traitor.[187] While Mihailović was in prison, his children did not come to see him, and only his wife visited him.[172] In 2005, Gordana Mihailović personally came to accept her father's posthumous award in the United States. Another son, Vojislav Mihailović, fought alongside his father and was killed in battle in May 1945.[188] His grandson, Vojislav Mihailović (born 1951, named after his uncle) is a Serbian politician, member of the Serbian Renewal Movement and later of the Serbian Democratic Renewal Movement. He was the mayor of Belgrade for one year, from 1999 to 2000 and ran unsuccessfully in the 2000 Yugoslav presidential elections.[189]

Legacy

Monument to Draža Mihailović on Ravna Gora

The Legion of Merit, awarded to Mihailović by U.S. president Harry Truman

Historians vary in their assessments of Mihailović. Tomasevich suggests one main cause of his defeat was his failure to grow professionally, politically or ideologically as his responsibilities increased, rendering him unable to face both the exceptional circumstances of the war and the complex situation of the Chetniks.[190] Tomasevich also criticizes Mihailović's loss of the Allied support through Chetnik collaboration with the Axis, as well as his doctrine of "passive resistance" which was perceived as idleness, stating "of generalship in the general there was precious little."[191] Pavlowitch also points to Mihailović's failure to grow and evolve during the conflict and describes him as a man "generally out of his depth".[192] Roberts asserts that Mihailović's policies were "basically static", that he "gambled all in the faith of an Allied victory," and that ultimately he was unable to control the Chetniks, who, "although hostile to the Germans and the Italians ... allowed themselves to drift into a policy of accommodations with both in the face of what they considered the greatest danger."[193]

Political views of Mihailović cover a wide range. After the war, Mihailović's wartime role was viewed in the light of his movement's collaboration, particularly in Yugoslavia where he was considered a collaborator convicted of high treason. Charles de Gaulle considered Mihailović a "pure hero" and always refused to have personal meetings with Tito, whom he considered as Mihailović's "murderer".[194][195] During the war, Churchill believed intelligence reports had shown that Mihailović had engaged "... in active collaboration with the Germans".[196] He observed that, under the pressure of German reprisals in 1941, Mihailović "drifted gradually into a posture where some of his commanders made accommodations with German and Italian troops to be left alone in certain mountain areas in return for doing little or nothing against the enemy", but concluded that "those who have triumphantly withstood such strains may brand his [Mihailović's] name, but history, more discriminating, should not erase it from the scroll of Serbian patriots."[197] In the United States, due to the efforts of Major Richard L. Felman and his friends, President Truman, on the recommendation of Eisenhower, posthumously awarded Mihailović the Legion of Merit for the rescue of American airmen by the Chetniks. The award and the story of the rescue was classified secret by the State Department so as not to offend the Yugoslav government.

"The unparalleled rescue of over 500 American Airmen from capture by the Enemy Occupation Forces in Yugoslavia during World War II by General Dragoljub Mihailovich and his Chetnik Freedom Fighters for which this "Legion of Merit" medal was awarded by President Harry S. Truman, also represents a token of deep personal appreciation and respect by all those rescued American Airmen and their descendants, who will be forever grateful." (NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF AMERICAN AIRMEN RESCUED BY GENERAL MihailovićH – 1985)

Generalfeldmarschall von Weichs, German commander-in-chief south east 1943–1945, in his interrogation statement in October 1945, wrote about Mihailović and his forces in section named "Groups Aiding Germany":

- "MIHAILOVIC 's troops once fought against our occupation troops out of loyalty to their King. At the same time they fought against TITO, because of anti—Communist convictions. This two front war could not last long, particularly when British support favored TITO. Consequently MIHAILOVIC showed pro-German leanings. There were engagements during which Serbian Chetniks fought TITO alongside German troops. On the other hand, hostile Chetnik groups were known to attack German supply trains in order to replenish their own stocks."

"MIHAILOVIC liked to remain in the background, and leave such affairs up to his subordinates. He hoped to bide his time with this play of power until an Anglo—American landing would provide sufficient support against TITO. Germany welcomed his support, however temporary. Chetnik reconnaissance activities were valued highly by our commanders."[198]

Almost sixty years after his death, on 29 March 2005, Mihailović's daughter, Gordana, was presented with the posthumous decoration by president George W. Bush.[199] The decision was controversial; in Croatia Zoran Pusić, head of the Civil Committee for Human Rights, protested against the decision and stated that Mihailović was directly responsible for the war crimes committed by the Chetniks.[200][201]

With the breakup of Yugoslavia and the renewal of ethnic nationalism, the historical perception of Mihailović's collaboration has been challenged by parts of the public in Serbia and other ethnic Serb-populated regions of the former Yugoslavia. In the 1980s, political and economic problems within Yugoslavia undermined faith in the communist regime, and historians in Serbia began a re-evaluation of Serbian historiography and proposed the rehabilitation of Mihailović and the Chetniks.[201] In the 1990s, during the Yugoslav Wars, several Serbian nationalist groups began calling themselves "Chetniks", while Serb paramilitaries often self-identified with them and were referred to as such.[202]Vojislav Šešelj's Serbian Radical Party formed the White Eagles, a paramilitary group considered responsible for war crimes and ethnic cleansing, which identified with the Chetniks.[203][204]Vuk Drašković's Serbian Renewal Movement was closely associated with the Serbian Guard, which was also associated with Chetniks and monarchism.[205] Reunions of Chetnik survivors and nostalgics and of Mihailović admirers have been held in Serbia[206] By the late 20th and early 21st century, Serbian history textbooks and academic works characterized Mihailović and the Chetniks as "fighters for a just cause", and Chetnik massacres of civilians and commission of war crimes were ignored or barely mentioned.[201] In 2004, Mihailović was officially rehabilitated in Serbia by an act of the Serbian Parliament.[207] In a 2009 survey carried out in Serbia, 34.44 percent of respondents favored annulling the 1946 verdict against Mihailović (in which he was found to be a traitor and Axis collaborator), 15.92 percent opposed, and 49.64 percent stated they did not know what to think.[208]

The revised image of Mihailović is not shared in non-Serbian post-Yugoslav nations. In Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina analogies are drawn between war crimes committed during World War II and those of the Yugoslav Wars, and Mihailović is "seen as a war criminal responsible for ethnic cleansing and genocidal massacres."[201] The differences were illustrated in 2004, when a Serbian basketball player, Milan Gurović, who has a tattoo of Mihailović on his left arm, was banned by the Croatian Ministry of the Interior Zlatko Mehun from traveling to Croatia for refusing to cover the tattoo, as its display was deemed equivalent to "provoking hatred or violence because of racial background, national identity or religious affiliation."[201][209] Serbian press and politicians reacted to the ban with surprise and indignation, while in Croatia the decision was seen as "wise and a means of protecting the player himself against his own stupidity."[201] In 2009, a Serb group based in Chicago offered a reward of $100,000.00 for help finding Mihailović's grave.[210] A commission formed by the Serbian government began an investigation and in 2010 suggested Mihailović may have been interred at Ada Ciganlija.[207]

General Dragoljub Mihailovich distinguished himself in an outstanding manner as Commander-in-Chief of the Yugoslavian Army Forces and later as Minister of War by organizing and leading important resistance forces against the enemy which occupied Yugoslavia, from December 1941 to December 1944. Through the undaunted efforts of his troops, many United States airmen were rescued and returned safely to friendly control. General Mihailovich and his forces, although lacking adequate supplies, and fighting under extreme hardships, contributed materially to the Allied cause, and were instrumental in obtaining a final Allied victory.

— Harry S. Truman, March 29, 1948

See also

- Operation Halyard

- George Musulin

- Operation Hydra (Yugoslavia)

- Yugoslavia and the Allies

Notes

^ Referred to by his supporters as Uncle Draža (Чича Дража, Čiča Draža).

^ Official name of the occupied territory. Hehn 1971, pp. 344–373; Pavlowitch 2002, p. 141.

^ Pavlowitch asserts that it cannot be determined who initiated the meeting, but Roberts attributes it to Matl. Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 65; Roberts 1973, p. 36.

^ Roberts quotes Konstantin Fotić, though he adds that even the latter, a Mihailović supporter, admits that the speech was "unfortunate". Roberts 1973, p. 94.

^ The text in Kriegstagebuch des Oberkommando der Wehrmacht for November 23rd 1943: Mihailovic hat nach sicherer Quelle seinen Unterführern den Befehl gegeben, mit den Deutschen zusammenzuarbeiten; er selbst können mit Rücksicht auf die Stimmung der Bevölkerung nicht in diesem Sinne hervortreten. Schramm 1963, p. 1304

^ Army Group F HQ Chief Intelligence Officer notice for the October 2nd Conference in Belgrade: Chetnik attitude remains uneven. Serbian Chetniks fight together with German troops against communist bands. DM himself even asked for German help to ensure the intended relocation of his HQ from NW Serbia to SW-Belgrade area but this intention was not carried out. In contrast, hostile attitude of the Chetniks in E-Bosnia, Herzegovina and S-Montenegro and movement of these forces to the coast in the area of Dubrovnik with the aim at to secure connenction with expected Engl. landing and to seek the protection from Red. From reliable source is known that DM expressly disapproves the anti-German attitude of these Chetniks. (German: Cetnik-Haltung weiterhin uneinheitlich. Serbische Cetniks kämpfen zusammen mit deutscher Truppe gegen komun. Banden. DM. selbst bat sogar um deutsche Hilfe zur Sicherung beabsichtigter Verlegung seines Hauptstabes von NW-Serbien in Raum SW Belgrad. Diese Absicht jedoch nicht durchgeführt. Demgegenüber feindselige Haltung der Cetniks in O-Bosnien, Herzegovina und S-Montenegro und Bewegung dieser Kräfte zur Küste in den Raum Dubrovnik mit dem Ziel, bei erwarteter engl. Landung Verbindung mit Alliierten aufzunehmen und Schutz gegen Rote zu suchen. Nach S.Qu. bekannt, dass DM. die deutschfeindliche Haltung dieser Cetniks ausdrücklich missbilligt). (National Archive and Research Administration, Washington, T311, Roll 194, 000105-6)

Citations

Footnotes

^ ab Tomasevich 1975, p. 271.

^ Draža Mihailović – Na krstu sudbine – Pero Simić: Laguna 2013

^ Miloslav Samardzic: General Mihailović Draža i OPSTA istoriia četničkog pokreta Draža General Mihailović and the general history of the Chetnik movement. 2 vols 4 Ed Novi pogledi, Kragujevac, 2005

^ Draža Mihailović – Na krstu sudbine – Pero Simić: Laguna 2013

^ Draža Mihailović – Na krstu sudbine – Pero Simić: Laguna 2013

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 125.

^ Mihailović 1946, p. 13.

^ Buisson 1999, p. 13.

^ ab Buisson 1999, pp. 26–27.

^ Buisson 1999, pp. 45–49.

^ Buisson 1999, pp. 55–56.

^ Buisson 1999, pp. 63–65.

^ ab Trew 1998, pp. 5–6.

^ Buisson 1999, pp. 66–68.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 53.

^ Milazzo 1975, pp. 12–13.

^ Milazzo 1975, p. 13.

^ abc Pavlowitch 2007, p. 54.

^ Freeman 2007, p. 123.

^ ab Roberts 1973, p. 21.

^ ab Roberts 1973, pp. 21–22.

^ ab Roberts 1973, p. 22.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 79.

^ Roberts 1973, p. 26.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 59.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 56.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 60.

^ Freeman 2007, pp. 124–126.

^ Roberts 1973, pp. 26–27.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 64.

^ abcd Pavlowitch 2007, p. 63.

^ ab Tomasevich 1975, p. 148.

^ Roberts 1973, p. 48.

^ Milazzo 1975, pp. 15–16.

^ ab Milazzo 1975, p. 21.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 141.

^ ab Tomasevich 1975, p. 140.

^ Ramet 2006, p. 133.

^ ab Milazzo 1975, p. 26.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 178.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 143.

^ Milazzo 1975, p. 33.

^ ab Milazzo 1975, p. 34.

^ ab Roberts 1973, p. 34.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 152.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 62–64.

^ abc Milazzo 1975, p. 35.

^ ab Roberts 1973, pp. 34–35.

^ abc Tomasevich 1975, p. 149.

^ Milazzo 1975, pp. 36–37.

^ Hoare 2006, p. 156.

^ ab Milazzo 1975, p. 38.

^ ab Tomasevich 1975, p. 150.

^ Miljuš 1982, p. 119.

^ ab Tomasevich 1975, p. 155.

^ ab Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 65–66.

^ abc Tomasevich 1975, p. 151.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 65.

^ ab Milazzo 1975, p. 37.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 196.

^ Karchmar 1987, p. 256.

^ ab Milazzo 1975, p. 39.

^ abcde Karchmar 1987, p. 272.

^ Trew 1998, pp. 86–88.

^ Milazzo 1975, p. 40.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 200.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 66–67, 96.

^ ab Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 66–67.

^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 214–216.

^ Roberts 1973, p. 38.

^ Roberts 1973, pp. 37–38.

^ ab Tomasevich 1975, p. 199.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 66.

^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 269–271.

^ Roberts 1973, p. 53.

^ Roberts 1973, pp. 53–54.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 184.

^ Roberts 1973, p. 56.

^ Roberts 1973, pp. 57–58.

^ abc Roberts 1973, p. 67.

^ Roberts 1973, pp. 58–62.

^ Roberts 1973, p. 40–41.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 210.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 219.

^ abc Pavlowitch 2007, p. 110.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 110–112.

^ Hoare 2006, p. 161.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 122–126.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 98.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 98–100.

^ Barker 1976, p. 162.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 100.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 127–128.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 256.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 169.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 259.

^ Hoare 2006, p. 148.

^ Hoare 2006, p. 143.

^ abc Malcolm 1994, p. 179.

^ Lerner 1994, p. 105.

^ Mulaj 2008, p. 42.

^ Milazzo 1975, p. 64.

^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 256–261.

^ Karchmar 1987, p. 397.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 79–80.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 170.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 179.

^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 171.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 112.

^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 258–259.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 158.

^ ab Hoare 2010, p. 1198.

^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 127.