Battle of Sekigahara

| Battle of Sekigahara | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sengoku period | |||||||||

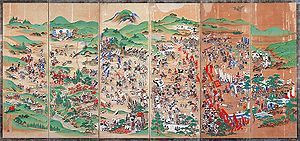

Edo period screen depicting the battle. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Ishida Mitsunari Mōri Terumoto Ōtani Yoshitsugu † Shimazu Yoshihiro Konishi Yukinaga Ukita Hideie Toda Shigemasa † Toda Katsushige † Gamo Yorisato † Natsuka Masaie † Shima Sakon † Shimazu Toyohisa † | Tokugawa Ieyasu Ii Naomasa (DOW) Hosokawa Tadaoki Honda Tadakatsu Kuroda Nagamasa Matsudaira Tadayoshi (WIA) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

120,000 initially,[1] 81,890 by the time of battle[2] | 75,000 initially,[1] 88,888 by the time of battle[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

5,000–32,000 dead ~23,000 defected | Unknown | ||||||||

Show map of Gifu Prefecture  Battle of Sekigahara (Japan) Show map of Japan | |||||||||

Commanders of Eastern Army (Tokugawa Force) | |

|---|---|

Tokugawa Ieyasu: 30,000 men | |

Maeda Toshinaga | |

Date Masamune | |

Katō Kiyomasa: 3,000 men | |

Fukushima Masanori: 6,000 men | |

Hosokawa Tadaoki: 5,000 men | |

Asano Yoshinaga: 6,510 men | |

Ikeda Terumasa: 4,560 men | |

Ikeda Sen: 200 women | |

Kuroda Nagamasa: 5,400 men | |

Katō Yoshiaki: 3,000 men | |

Komatsuhime | |

Tanaka Yoshimasa: 3,000 men | |

Tōdō Takatora: 2,490 men | |

Sanada Nobuyuki | |

Mogami Yoshiaki | |

Yamauchi Katsutoyo: 2,058 men | |

Hachisuka Yoshishige | |

Honda Tadakatsu: 500 men | |

Terasawa Hirotaka: 2,400 men | |

Ikoma Kazumasa: 1,830 men | |

Ii Naomasa: 3,600 men | |

Matsudaira Tadayoshi: 3,000 men | |

Oda Nagamasu: 450 men | |

Tsutsui Sadatsugu: 2,850 men | |

Kanamori Nagachika: 1,140 men | |

Tomita Nobutaka | |

Furuta Shigekatsu: 1,200 men | |

Wakebe Mitsuyoshi | |

Horio Tadauji | |

Nakamura Kazutada | |

Arima Toyouji: 900 men | |

Kyōgoku Takatomo: 3,000 men | |

Commanders of Western Army (Ishida Force) | |

Mōri Terumoto (official head of the alliance) (not present) | |

Uesugi Kagekatsu | |

Maeda Toshimasa (Brother of Maeda Toshinaga) | |

Ukita Hideie: 17,000 men | |

Shimazu Yoshihiro: 1,500 men | |

Kobayakawa Hideaki (defected): 15,600 men | |

Ishida Mitsunari (de facto head of the alliance): 4,000 men | |

Konishi Yukinaga: 4,000 men | |

Mashita Nagamori | |

Ogawa Suketada (defected): 2,100 men | |

Ōtani Yoshitsugu: 600 men | |

Wakisaka Yasuharu (defected): 990 men | |

Ankokuji Ekei: 1,800 men | |

Satake Yoshinobu | |

Oda Hidenobu | |

Chōsokabe Morichika: 6,600 men | |

Kutsuki Mototsuna (defected): 600 men | |

Akaza Naoyasu (defected): 600 men | |

Kikkawa Hiroie (defected): 3,000 men | |

Natsuka Masaie: 1,500 men | |

Mōri Hidemoto: 15,000 men | |

Tachibana Ginchiyo | |

Toda Katsushige: 1,500 men | |

Sanada Masayuki | |

Sanada Yukimura: 40 | |

Shima Sakon: 1,000 men | |

Gamo Bitchu: 1,000 men | |

Ōtani Yoshikatsu: 3,500 men | |

Shimazu Toyohisa: 750 men | |

Vassals of the Toyotomi: 2,000 men | |

The Battle of Sekigahara (Shinjitai: 関ヶ原の戦い; Kyūjitai: 關ヶ原の戰い, Hepburn romanization: Sekigahara no Tatakai) was a decisive battle on October 21, 1600 (Keichō 5, 15th day of the 9th month), that preceded the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Tokugawa Ieyasu took three more years to consolidate his position of power over the Toyotomi clan and the various daimyō, but Sekigahara is widely considered to be the unofficial beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate, the last shogunate to control Japan.

Contents

1 Background

2 Prelude

3 Troop deployment

4 Battle

4.1 Fall of the Western Army

4.2 Late arrivals

5 Aftermath

5.1 Rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate

5.2 Seeds of dissent from Sekigahara

6 Kokudaka of daimyō

7 Miyamoto Musashi

8 Sekigahara Battlefield

9 In popular culture

10 References

11 Bibliography

12 Further reading

13 External links

Background

Oda Nobunaga had slowly consolidated control over much of Japan and was in control of the Shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki. Yoshiaki tried to escape this predicament in 1573 by attacking Nobunaga, but failed and was exiled, thus ending the Ashikaga shogunate. Nobunaga ruled unopposed until he was betrayed by his own retainer Akechi Mitsuhide and died at the Honnō-ji Incident of 1582. Toyotomi Hideyoshi quickly avenged his master and consolidated control over Japan. Hideyoshi had risen from humble roots – his father was an ashigaru (foot-soldier) – to become the ruler of Japan. His death created a power vacuum which ultimately was resolved by the outcome at Sekigahara.[3][4]

Even though Toyotomi Hideyoshi unified Japan and consolidated his power following the Siege of Odawara in 1590, his failures in his invasions of Korea significantly weakened the Toyotomi clan's power as well as the support of the loyalists and bureaucrats who continued to serve and support the Toyotomi clan after Hideyoshi's death during the second invasion.[4] The presence of Hideyoshi and his brother Hidenaga kept the two main factions of the time, which rallied behind Ishida Mitsunari and Tokugawa Ieyasu respectively, from anything more than quarrelling, but when both of them died, the conflicts were exacerbated and developed into open hostilities.[4][5] With no appointed shōgun over the armies, this left a power vacuum in the Japanese government.

Most notably, Katō Kiyomasa and Fukushima Masanori were publicly critical of the bureaucrats, especially Ishida Mitsunari and Konishi Yukinaga. Tokugawa Ieyasu took advantage of this situation, and recruited them, redirecting the animosity to weaken the Toyotomi clan.[6]

Prelude

Tokugawa Ieyasu was unrivalled in terms of seniority, rank, reputation and overall influence within the regency of the Toyotomi clan after the death of regent Maeda Toshiie. Rumours started to spread stating that Ieyasu, at that point the only surviving contemporary ally of Oda Nobunaga, would take over Hideyoshi's legacy just as Nobunaga's was taken. This was especially evident amongst the loyalist bureaucrats, who suspected Ieyasu of agitating unrest amongst Toyotomi's former vassals.

Later, a supposed conspiracy to assassinate Ieyasu surfaced, and many Toyotomi loyalists, including Maeda Toshiie's son, Toshinaga, were accused of taking part and forced to submit to Ieyasu's authority.[6] However, Uesugi Kagekatsu, one of Hideyoshi's appointed regents, defied Ieyasu by building up his military. When Ieyasu officially condemned him and demanded that he come to Kyoto to explain himself, Kagekatsu's chief advisor, Naoe Kanetsugu responded with a counter-condemnation that mocked Ieyasu's abuses and violations of Hideyoshi's rules, and Ieyasu was infuriated.[7]

Afterwards, Ieyasu summoned the help of various supporters and led them northward to attack the Uesugi clan. Many of them were at that moment besieging Hasedō though. Ishida Mitsunari, grasping the opportunity created by the chaos, rose up in response and created an alliance to challenge Ieyasu's supporters.

Troop deployment

Ishida, in his home Sawayama Castle, met with Ōtani Yoshitsugu, Mashita Nagamori, and Ankokuji Ekei. Here, they forged the alliance, and invited Mōri Terumoto to be its head. Thus formed what came to be referred to as the Western Army. Mōri seized Osaka Castle for their base of operations, since most of Tokugawa’s forces had vacated the area to attack Uesugi.[8]

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Ishida wanted to reinforce Mōri at the impregnable Osaka Castle. This would let Ishida control the capital of Kyoto and challenge the Tokugawa. To this end, Ishida’s forces headed for Gifu Castle in order to use it as a staging area to move on Kyoto, since it was controlled by his ally Oda Hidenobu.[4]

Back in Edo, Tokugawa Ieyasu received news of the situation in the Kansai region and decided to deploy his forces. Ieyasu himself commanded 30,000 men and his subordinates led another 40,000 men. This made up the bulk of what would later be called the Eastern Army.[9] He had some former Toyotomi daimyō engage with the Western Army, while he split his troops and marched west on the Tōkaidō towards Osaka.

Since the Tokugawa army departed from Edo, it could only take two roads, both of which converged on Gifu Castle. Ieyasu marched on Gifu while Ishida Mitsunari was delayed at Fushimi Castle. This fortress was a halfway point between Osaka and Kyoto and was controlled by the Tokugawa ally Torii Mototada.[10] Ishida could not risk leaving a force that could attack his rear, so he marched on it. It took him ten days to capture Fushimi, and in that time Gifu Castle had fallen. This forced Ishida Mitsunari to retreat southward in the rain.[4]

Tired from a day's march and their gunpowder wet from the rain, Ishida and his forces stopped at Sekigahara. "Ishida deployed his troops in a strong defensive position, flanked by two streams with high ground on the opposite banks."[attribution needed] His right flank was reinforced by daimyō Kobayakawa Hideaki on Mount Matsuo.[11]

On October 20, 1600, Ieyasu learned that Ishida Mitsunari had deployed his troops at Sekigahara in a defensive position. They had been following the Western Army, and benefited from considerably better weather. At dawn of the next day, the Tokugawa advance guard stumbled into Ishida's army. Neither side saw each other due to the dense fog caused by the earlier rain. Both sides panicked and withdrew, but this resulted in both sides being aware of their adversary's presence.[11]

Ishida held his current defensive position and Ieyasu deployed his own forces. He sent his allies' forces in a line to the front, and held his own troops in reserve. Around 8:00am, wind blew away the fog, and both sides noticed their respective adversary's positions. Last-minute orders were issued and the battle began.[12]

Battle

Initially, the Eastern Army had 75,000 men, while the Western Army numbered 120,000.[1] Ieyasu had also sneaked in a supply of arquebuses.[11] Knowing that the Tokugawa forces were heading towards Osaka, Ishida decided to abandon his positions and marched to Sekigahara. Even though the Western army had tremendous tactical advantages, Ieyasu had already been in contact with many of the daimyō in the Western Army for months, promising them land and leniency after the battle should they switch sides.[11]

The battle started when Fukushima Masanori, the leader of the Tokugawa advance guard, charged north from the Eastern Army's left flank along the Fuji River against the Western Army's right centre. The ground was still muddy from the previous day's rain, so the conflict there devolved into something more primal. Ieyasu then ordered attacks from his right and his centre against the Western Army’s left in order to support Fukushima's attack.[11]

This left the Western Army's centre unscathed, so Ishida ordered this unit under the command of Shimazu Yoshihiro to reinforce his right flank. Shimazu refused as daimyō of the day only listened to respected commanders, which Ishida was not.[11]

Recent scholarship by Professor Yoshiji Yamasaki of Toho University has indicated that the Mōri faction had reached a secret agreement with the Tokugawa two weeks earlier, pledging neutrality at the decisive battle in exchange for a guarantee of territorial preservation, and was a strategic decision on Mōri Terumoto's part that later backfired.

Fukushima's attack was slowly gaining ground, but this came at the cost of exposing their flank to attack from across the Fuji River by Ōtani Yoshitsugu, who took advantage of this opportunity. Just past Ōtani's forces were those of Kobayakawa Hideaki on Mount Matsuo.[11]

Kobayakawa was one of the daimyō who had been courted by Tokugawa. Even though he had agreed to defect to the Tokugawa side, in the actual battle he was hesitant and remained neutral. As the battle grew more intense, Ieyasu finally ordered his arquebuses to fire at Kobayakawa's position on Mount Matsuo to force a choice. At that point Kobayakawa joined the battle as a member of the Eastern Army. His forces charged Ōtani's position, which did not end well for Kobayakawa. Ōtani's forces had dry gunpowder, so they opened fire on the turncoats, making the charge of 16,000 men mostly ineffective.[12] However, he was already engaging forces under the command of Tōdō Takatora, Kyōgoku Takatsugu, and Oda Yūraku when Kobayakawa charged. At this point, the buffer Ōtani established was outnumbered. Seeing this, Western Army generals Wakisaka Yasuharu, Ogawa Suketada, Akaza Naoyasu, and Kutsuki Mototsuna switched sides, turning the tide of battle.[13]

Fall of the Western Army

Heavily outnumbered, Ōtani had no choice but to retreat. This left the Western Army's right flank wide open, so Fukushima and Kobayakawa began to roll it up. Thus Ishida's right flank was destroyed and his centre was being pushed back, so he retreated.[12]

Ishida’s only remaining forces were on Mount Nangu. However, these forces were there for a reason. Kikkawa Hiroie was one of the commanders on the mountain. Kikkawa's troops formed the front lines of the Mōri army, which was commanded by his cousin Mōri Hidemoto. Earlier, when Hidemoto decided to attack the Tokugawa forces, Hiroie refused to comply, stating he was busy eating and asked to be left alone. This in turn prevented the Chōsokabe army, which deployed behind the Mōri clan, from attacking.[14] When Ishida arrived, Kikkawa betrayed him as well. He kept the Mōri army at bay, and since Ishida had no more support, he was defeated.[12]

The Western Army disintegrated afterwards with the commanders scattering and fleeing. Some, like Ukita Hideie managed to escape, at least initially.[15] Many others did not. Shima Sakon was shot and fatally wounded by a round from an arquebus[16] and Ōtani Yoshitsugu committed suicide. Ishida, Yukinaga and Ekei were some of those who were captured and a few, like Mōri Terumoto and Shimazu Yoshihiro were able to return to their home provinces.[17] Ishida himself was later executed.[15]

Late arrivals

Both sides had forces that did not arrive at Sekigahara in time to participate due to other battles. Ieyasu's son Hidetada led another group through Nakasendō. However, Hidetada's forces were bogged down as he attempted to besiege Sanada Masayuki's Ueda Castle against his father's direct orders. Even though the Tokugawa forces numbered some 38,000, an overwhelming advantage over the Sanada's mere 2,000, they were still unable to capture the famous strategist's well-defended position.[10]

At the same time, 15,000 Toyotomi troops were being held up by 500 troops under Hosokawa Yūsai at Tanabe Castle in present-day Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture.[18] Some among the 15,000 troops respected Hosokawa so much they intentionally slowed their pace. Due to these incidents, a large number of troops from both sides failed to show up in time for the battle.[19] If either of these armies participated in the conflict, it could have ended quite differently.[20]

Aftermath

Rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate

Following the public execution of Ishida Mitsunari, Konishi Yukinaga and Ankokuji Ekei, the influence and reputation of the Toyotomi clan and its remaining loyalists drastically decreased.[15] Tokugawa Ieyasu redistributed the lands and fiefs of the participants, generally rewarding those who assisted him and displacing, punishing, or exiling those who fought against him. In doing so, he gained control of many former Toyotomi territories.[21]

At the time, the battle was considered only an internal conflict between Toyotomi vassals. However, after Ieyasu was named shōgun in 1603 by Emperor Go-Yōzei,[22][15] a position that had been left vacant since the fall of the Ashikaga shōgunate 27 years earlier,[4] the battle was perceived as a more important event. In 1664, Hayashi Gahō, Tokugawa historian and rector of Yushima Seidō, summarised the consequences of the battle: "Evil-doers and bandits were vanquished and the entire realm submitted to Lord Ieyasu, praising the establishment of peace and extolling his martial virtue. That this glorious era that he founded may continue for ten thousands upon ten thousands of generations, coeval with heaven and earth."[23]

Seeds of dissent from Sekigahara

While most clans were content with their new status, there were many clans, especially those on the Western side, who became bitter about their displacement or what they saw as a dishonorable defeat or punishment. Three clans in particular did not take the aftermath of Sekigahara lightly:

- The Mōri clan, headed by Mōri Terumoto, remained angry toward the Tokugawa shogunate for being displaced from their fief, Aki, and being relocated to the Chōshū Domain, even though the clan did not take part in the battle at all.[17]

- The Shimazu clan, headed by Shimazu Yoshihiro, blamed the defeat on its poor intelligence-gathering, and while they were not displaced from their home province of Satsuma, they did not become completely loyal to the Tokugawa shōgunate either. Taking advantage of its large distance between Edo and the island of Kyūshū as well as its improved espionage, the Shimazu clan demonstrated that it was virtually an autonomous kingdom independent from the Tokugawa shōgunate during its last days.

- The Chōsokabe clan, headed by Chōsokabe Morichika, was stripped of its title and domain of Tosa and sent into exile. Former Chōsokabe retainers never quite came to terms with the new ruling family, the Yamauchi clan, which made a distinction between its own retainers and former Chōsokabe retainers, giving them lesser status as well as discriminatory treatment. This class distinction continued even generations after the fall of the Chōsokabe clan.

The descendants of these three clans would in two centuries collaborate to bring down the Tokugawa shogunate, leading to the Meiji Restoration.

Kokudaka of daimyō

○ = Main daimyōs who participated in Battle of Sekigahara

● = Daimyōs who defected

Daimyō | Kokudaka (ten thousands) | Daimyō | Kokudaka (ten thousands) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Army | 120.5 | Eastern Army | 256.0 | ||

| 120.0 | 84.0 | ||||

| 54.0 | 58.0 | ||||

| 73.0 | 20.0 | ||||

| 57.0 | 24.0 | ||||

| 19.4 | 18.0 | ||||

Konishi Yukinaga ○ | 20.0 | 16.0 | |||

Mashita Nagamori | 20.0 | 15.2 | |||

| 7.0 | 18.0 | ||||

| 5.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| 3.3 | 10.0 | ||||

| 6.0 | 11.0 | ||||

| 37.0 | 24.0 | ||||

| 13.5 | 5.9 | ||||

| 22.0 | 17.7 | ||||

| 1.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| 2.0 | Terazawa Hirotaka ○ | 8.0 | |||

| 14.2 | 15.0 | ||||

| 5.0 | 12.0 | ||||

| 20.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| 1.0 | 20.0 | ||||

| 3.8 | 10.0 |

Miyamoto Musashi

Legend has it that the rōnin Miyamoto Musashi was present at the battle among Ukita Hideie's army and escaped the defeat of Hideie's forces unharmed. Musashi would have been around 16 years of age at the time. There is no hard evidence to prove if Musashi was present or not for the battle. According to one account, the Musashi yuko gamei, "Musashi's achievements stood out from the crowd, and were known by the soldiers in all camps."[24] Musashi is reticent on the matter, writing only that he had "participated in over six battles since my youth".[25]

Sekigahara Battlefield

Present day Sekigahara battlefield memorials

The site of the Battle of Sekigahara was designated a National Historic Site of Japan in 1931. The site encompasses the sites of the initial position of Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康最初陣地), the final position of Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康最後陣地), the position of Ishida Mitsunari (石田三成陣地), the Okayama beacon (岡山烽火場), the grave of Ōtani Yoshitsugu (大谷吉隆墓), the east kubizuka (東首塚), and the west kubizuka (西首塚)[26]

In popular culture

- The battle of Sekigahara is depicted at the beginning of the 1954 movie Samurai I, the first of Hiroshi Inagaki's Samurai Trilogy.

- The related political intrigues leading up to the battle was the historical foundation for James Clavell's 1975 novel, Shōgun, later televised in 1980.

- A fictionalized version of the battle is featured in the beginning sequence of the film Journey of Honor (1991), starring Sho Kosugi.

- Re-enacted in the 2008 BBC Docudrama series Heroes and Villains.

- This battle was figured in the manga and anime series Samurai Deeper Kyo.

- This battle was figured in the manga Vagabond.

- This battle was featured as a campaign in Age of Empires III: The Asian Dynasties.

- The battle features as a playable "Historical Battle" in the 2011 real-time strategy game Total War: Shogun 2 in the side of Ishida Mitsunari.

- The battle features heavily into the strategy video game Kessen.

- This battle is depicted in Sengoku Basara: The Last Party and Sengoku Basara: End of Judgement.

- The battle of Sekigahara is fictionalized in the Young Samurai series as the Battle of Nakasendo.

- The low-complexity block wargame Sekigahara: Unification of Japan, by GMT Games is based on Tokugawa's campaign, featuring a card based combat system without using dice.

- The battle of Sekigahara is featured in the Samurai Warriors series.

- This battle is very accurately depicted in the NHK historical drama Ten Chi Jin.

- This battle was figured in the manga and anime series Drifters.

- The 2017 video game Nioh is centered around this battle and the events leading up to it.

- The movie Sekigahara from 2017 retells the battle.

- The MMORPG video game Onigiri, made by Cyberstep, features a section based on the battle of Sekigahara, in which all participants are recast as yōkai from Japanese folklore, notably Tokugawa Ieyasu as a tanuki and Ishida Mitsunari as a kyuubi no kitsune.

References

^ abc Davis 1999, p. 204.

^ ab Bryant 1995.

^ Yoshikawa, Eiji. Taiko. Kodansha International..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcdef Davis 1999, p. 205.

^ Bryant 1995, p. 8.

^ ab Bryant 1995, p. 10.

^ Bryant 1995, pp. 12, 89.

^ Bryant 1995, pp. 12, 90.

^ Davis 1999, pp. 205–206.

^ ab Bryant 1995, pp. 89–90.

^ abcdefg Davis 1999, p. 206.

^ abcd Davis 1999, p. 207.

^ Bryant 1995, p. 73.

^ Bryant 1995, pp. 66, 68.

^ abcd Bryant 1995, p. 80.

^ Bryant 1995, p. 51.

^ ab Bryant 1995, p. 79.

^ "Tanabe Castle Profile". jcastle.info.

^ Bryant 1995, p. 91.

^ Bryant 1995, p. 84.

^ Bryant 1995, p. 82.

^ Davis 1999, p. 208.

^ Hoffman, Michael. "A man in the soul of Japan", Japan Times (Tokyo). September 10, 2006.

^ Wilson 2004, p. 33.

^ Wilson 2004, p. 34.

^ "関ヶ原古戦場" [Sekigahara ko-senjō] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs.

Bibliography

Bryant, Anthony (1995). Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle For Power. Osprey Campaign Series. 40. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-395-7.

Davis, Paul (1999). "Sekigahara, 21 October 1600". 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9.

Wilson, William Scott (2004). The Lone Samurai: The Life of Miyamoto Musashi. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Further reading

Paul Davis used the following sources to compile the chapter "Sekigahara, 21 October 1600" in 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present "Sekigahara, 21 October 1600."

- Sadler, A.L. The Maker of Modern Japan: The Life of Tokugawa Ieyasu London: George Allen & Unwin, 1937

- Sansom, George. A History of Japan from 1334–1615 Stanford University Press, 1961

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Samurai: A Military History New York: Macmillan, 1977

External links

SengokuDaimyo.com The website of samurai author and historian Anthony J. Bryant. Bryant is the author of the above-mentioned Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power.- Several strategy war games based on the battle: Sekigahara: Unification of Japan