Tagalog language

| Tagalog | |

|---|---|

.mw-parser-output .script-baybayinfont-family:"Tagalog Doctrina 1593","Baybayin Lopez","Tagalog Stylized","Noto Sans Tagalog",Code2000 Wikang Tagalog | |

| Pronunciation | [tɐˈɡaːloɡ] |

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Manila, Southern Tagalog and Central Luzon |

| Ethnicity | Tagalog people |

Native speakers | 28 million (2007)[1] 45 million L2 speakers (2013)[2] Total: 70+ million (2000)[3] |

Language family | Austronesian

|

Early forms | Proto-Philippine

|

Standard forms | Filipino |

| Dialects |

|

Writing system | Latin (Tagalog/Filipino alphabet), Philippine Braille Baybayin (historical) |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tl |

| ISO 639-2 | tgl |

| ISO 639-3 | tgl – inclusive codeIndividual code: fil – Filipino |

| Glottolog | taga1280 Tagalogic[4]taga1269 Tagalog/Filipino[5] |

| Linguasphere | 31-CKA |

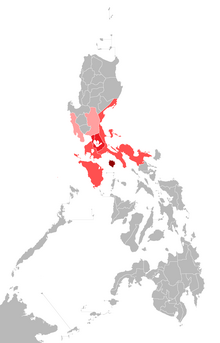

Predominantly Tagalog-speaking regions in the Philippines. The color-schemes represent the four dialect zones of the language: Northern, Central, Southern and Marinduque. The majority of residents in Camarines Norte and Camarines Sur speak Bikol as their first language but these provinces nonetheless have significant Tagalog minorities. In addition, Tagalog is used as a second language throughout the Philippines. | |

Tagalog (/təˈɡɑːlɒɡ/;[6]Tagalog pronunciation: [tɐˈɡaːloɡ]) is an Austronesian language spoken as a first language by a quarter of the population of the Philippines and as a second language by the majority.[7][8] Its standardized form, officially named Filipino, is the national language of the Philippines, and is one of two official languages alongside English.

It is related to other Philippine languages, such as the Bikol languages, Ilocano, the Visayan languages, Kapampangan, and Pangasinan, and more distantly to other Austronesian languages, such as the Formosan languages of Taiwan, Malay (Malaysian and Indonesian), Hawaiian, Māori, and Malagasy. Tagalog is the predominant language used in the tanaga, a type of Filipino poem and the indigenous poetic art of the Tagalog people.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Historical changes

1.2 Official status

1.3 Controversy

1.4 Use in education

2 Classification

2.1 Dialects

2.2 Geographic distribution

2.3 Accents

2.4 Code-switching

3 Phonology

3.1 Vowels

3.2 Consonants

3.3 Lexical stress

4 Grammar

5 Writing system

5.1 Baybayin

5.2 Latin alphabet

5.2.1 Abecedario

5.2.2 Abakada

5.2.3 Revised alphabet

5.2.4 ng and mga

5.3 pô/hô and opò/ohò

6 Vocabulary and borrowed words

6.1 Tagalog words of foreign origin

6.2 Cognates with other Philippine languages

7 Austronesian comparison chart

8 Religious literature

9 Examples

9.1 Lord's Prayer

9.2 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

9.3 Numbers

9.4 Months and days

9.5 Time

10 Common phrases

10.1 Proverbs

11 Majority provinces

11.1 Northern Tagalog

11.2 Central Tagalog

11.3 Southern Tagalog

12 See also

13 References

14 External links

History

The Tagalog Baybayin script

The word Tagalog is derived from the endonym taga-log ("river dweller"), composed of tagá- ("native of" or "from") and ilog ("river"). Linguists such as Dr. David Zorc and Dr. Robert Blust speculate that the Tagalogs and other Central Philippine ethno-linguistic groups originated in Northeastern Mindanao or the Eastern Visayas.[9][10]

The first written record of Tagalog is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which dates to 900 CE and exhibits fragments of the language along with Sanskrit, Old Malay, Javanese and Old Tagalog. The first known complete book to be written in Tagalog is the Doctrina Christiana (Christian Doctrine), printed in 1593. The Doctrina was written in Spanish and two transcriptions of Tagalog; one in the ancient, then-current Baybayin script and the other in an early Spanish attempt at a Latin orthography for the language.

Throughout the 333 years of Spanish rule, various grammars and dictionaries were written by Spanish clergymen. In 1610, the Dominican priest Francisco Blancas de San Jose published the “Arte y reglas de la Lengua Tagala” (which was subsequently revised with two editions in 1752 and 1832) in Bataan. In 1613, the Franciscan priest Pedro de San Buenaventura published the first Tagalog dictionary, his "Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala” in Pila, Laguna.

The first substantial dictionary of the Tagalog language was written by the Czech Jesuit missionary Pablo Clain in the beginning of the 18th century. Clain spoke Tagalog and used it actively in several of his books. He prepared the dictionary, which he later passed over to Francisco Jansens and José Hernandez.[11] Further compilation of his substantial work was prepared by P. Juan de Noceda and P. Pedro de Sanlucar and published as Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala in Manila in 1754 and then repeatedly[12] reedited, with the last edition being in 2013 in Manila.[13]

Among others, Arte de la lengua tagala y manual tagalog para la administración de los Santos Sacramentos (1850) in addition to early studies[14] of the language.

The indigenous poet Francisco Baltazar (1788–1862) is regarded as the foremost Tagalog writer, his most notable work being the early 19th-century epic Florante at Laura.[15]

Historical changes

Diariong Tagalog (Tagalog Newspaper), the first bilingual newspaper in the Philippines founded in 1882 written in both Tagalog and Spanish.

Tagalog differs from its Central Philippine counterparts with its treatment of the Proto-Philippine schwa vowel *ə. In most Bikol and Visayan languages, this sound merged with /u/ and [o]. In Tagalog, it has merged with /i/. For example, Proto-Philippine *dəkət (adhere, stick) is Tagalog dikít and Visayan & Bikol dukot.

Proto-Philippine *r, *j, and *z merged with /d/ but is /l/ between vowels. Proto-Philippine *ŋajan (name) and *hajək (kiss) became Tagalog ngalan and halík.

Proto-Philippine *R merged with /ɡ/. *tubiR (water) and *zuRuʔ (blood) became Tagalog tubig and dugô.

Official status

Tagalog was declared the official language by the first revolutionary constitution in the Philippines, the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.[16]

In 1935, the Philippine constitution designated English and Spanish as official languages, but mandated the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.[17] After study and deliberation, the National Language Institute, a committee composed of seven members who represented various regions in the Philippines, chose Tagalog as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[18][19] President Manuel L. Quezon then, on December 30, 1937, proclaimed the selection of the Tagalog language to be used as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[18] In 1939, President Quezon renamed the proposed Tagalog-based national language as Wikang Pambansâ (national language).[19] Under the Japanese puppet government during World War II, Tagalog as a national language was strongly promoted; the 1943 Constitution specifying: The government shall take steps toward the development and propagation of Tagalog as the national language.".

In 1959, the language was further renamed as "Pilipino".[19] Along with English, the national language has had official status under the 1973 constitution (as "Pilipino")[20] and the present 1987 constitution (as Filipino).

Controversy

The adoption of Tagalog in 1937 as basis for a national language is not without its own controversies. Instead of specifying Tagalog, the national language was designated as Wikang Pambansâ ("National Language") in 1939.[18][21] Twenty years later, in 1959, it was renamed by then Secretary of Education, José Romero, as Pilipino to give it a national rather than ethnic label and connotation. The changing of the name did not, however, result in acceptance among non-Tagalogs, especially Cebuanos who had not accepted the selection.[19]

The national language issue was revived once more during the 1971 Constitutional Convention. Majority of the delegates were even in favor of scrapping the idea of a "national language" altogether.[22] A compromise solution was worked out—a "universalist" approach to the national language, to be called Filipino rather than Pilipino. The 1973 constitution makes no mention of Tagalog. When a new constitution was drawn up in 1987, it named Filipino as the national language.[19] The constitution specified that as the Filipino language evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages. However, more than two decades after the institution of the "universalist" approach, there seems to be little if any difference between Tagalog and Filipino.

Many of the older generation in the Philippines feel that the replacement of English by Tagalog in the popular visual media has had dire economic effects regarding the competitiveness of the Philippines in trade and overseas remittances.[23]

Use in education

Upon the issuance of Executive Order No. 134, Tagalog was declared as basis of the National Language. On 12th of April 1940, Executive No. 263 was issued ordering the teaching of the national language in all public and private schools in the country. [24]

Article XIV, Section 7 of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines specifies, in part:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Subject to provisions of law and as the Congress may deem appropriate, the Government shall take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.

— [25]

The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein.

— [25]

In 2009, the Department of Education promulgated an order institutionalizing a system of mother-tongue based multilingual education ("MLE"), wherein instruction is conducted primarily in a student's mother tongue (one of the various regional Philippine languages) until at least grade three, with additional languages such as Filipino and English being introduced as separate subjects no earlier than grade two. In secondary school, Filipino and English become the primary languages of instruction, with the learner's first language taking on an auxiliary role.[26] After pilot tests in selected schools, the MLE program was implemented nationwide from School Year (SY) 2012-2013.[27][28]

It is the first language of a quarter of the population of the Philippines (particularly in Central Luzon) and a second language of the majority.[29]

Classification

Tagalog is a Central Philippine language within the Austronesian language family. Being Malayo-Polynesian, it is related to other Austronesian languages, such as Malagasy, Javanese, Malay (Malaysian and Indonesian), Tetum (of Timor), and Yami (of Taiwan).[30] It is closely related to the languages spoken in the Bicol Region and the Visayas islands, such as the Bikol group and the Visayan group, including Waray-Waray, Hiligaynon and Cebuano.[30]

Dialects

The Ten Commandments in Tagalog.

At present, no comprehensive dialectology has been done in the Tagalog-speaking regions, though there have been descriptions in the form of dictionaries and grammars of various Tagalog dialects. Ethnologue lists Manila, Lubang, Marinduque, Bataan (Western Central Luzon), Batangas, Bulacan (Eastern Central Luzon), Tanay-Paete (Rizal-Laguna), and Tayabas (Quezon) as dialects of Tagalog; however, there appear to be four main dialects, of which the aforementioned are a part: Northern (exemplified by the Bulacan dialect), Central (including Manila), Southern (exemplified by Batangas), and Marinduque.

Some example of dialectal differences are:

- Many Tagalog dialects, particularly those in the south, preserve the glottal stop found after consonants and before vowels. This has been lost in Standard Tagalog. For example, standard Tagalog ngayón (now, today), sinigáng (broth stew), gabí (night), matamís (sweet), are pronounced and written ngay-on, sinig-ang, gab-i, and matam-is in other dialects.

- In Teresian-Morong Tagalog, [ɾ] is usually preferred over [d]. For example, bundók, dagat, dingdíng, and isdâ become bunrók, ragat, ringríng, and isrâ, e.g. "sandók sa dingdíng" becoming "sanrók sa ringríng".

- In many southern dialects, the progressive aspect infix of -um- verbs is na-. For example, standard Tagalog kumakain (eating) is nákáin in Quezon and Batangas Tagalog. This is the butt of some jokes by other Tagalog speakers, for should a Southern Tagalog ask nákáin ka ba ng patíng? ("Do you eat shark?"), he would be understood as saying "Has a shark eaten you?" by speakers of the Manila Dialect.

- Some dialects have interjections which are considered a regional trademark. For example, the interjection ala e! usually identifies someone from Batangas as does hane?! in Rizal and Quezon provinces.

Bulacan has a distinct and deep Tagalog words.

Perhaps the most divergent Tagalog dialects are those spoken in Marinduque.[31] Linguist Rosa Soberano identifies two dialects, western and eastern, with the former being closer to the Tagalog dialects spoken in the provinces of Batangas and Quezon.

One example is the verb conjugation paradigms. While some of the affixes are different, Marinduque also preserves the imperative affixes, also found in Visayan and Bikol languages, that have mostly disappeared from most Tagalog early 20th century; they have since merged with the infinitive.

Manila Tagalog | Marinduqueño Tagalog | English |

|---|---|---|

| Susulat siná María at Esperanza kay Juan. | Másúlat da María at Esperanza kay Juan. | "María and Esperanza will write to Juan." |

| Mag-aaral siya sa Maynilà. | Gaaral siya sa Maynilà. | "[He/She] will study in Manila." |

| Maglutò ka na. | Paglutò. | "Cook now." |

| Kainin mo iyán. | Kaina yaan. | "Eat it." |

| Tinatawag tayo ni Tatay. | Inatawag nganì kitá ni Tatay. | "Father is calling us." |

| Tútulungan ba kayó ni Hilario? | Atulungan ga kamo ni Hilario? | "Is Hilario going to help you?" |

Northern and central dialects form the basis for the national language.

Geographic distribution

No dumping sign along the highway in the Laguna province, Philippines.

Welcome sign in Bay, Laguna.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, as of 2014 there were 100 million people living in the Philippines, where almost all of whom will have some basic level of understanding of the language. The Tagalog homeland, Katagalugan, covers roughly much of the central to southern parts of the island of Luzon—particularly in Aurora, Bataan, Batangas, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Metro Manila, Nueva Ecija, Quezon, Rizal and Zambales. Tagalog is also spoken natively by inhabitants living on the islands of Marinduque and Mindoro, as well as Palawan to a lesser extent. It is spoken by approximately 64 million Filipinos, 96% of the household population;[32] 22 million, or 28% of the total Philippine population,[33] speak it as a native language.

Tagalog speakers are found in other parts of the Philippines as well as throughout the world, though its use is usually limited to communication between Filipino ethnic groups. In[update] 2010, the US Census bureau reported (based on data collected in 2007) that in the United States it was the fourth most-spoken language at home with almost 1.5 million speakers, behind Spanish or Spanish Creole, French (including Patois, Cajun, Creole), and Chinese. Tagalog ranked as the third most spoken language in metropolitan statistical areas, behind Spanish and Chinese but ahead of French.[34]

Accents

The Tagalog language also boasts accentations unique to some parts of Tagalog-speaking regions. For example, in some parts of Manila, a strong pronunciation of i exists and vowel-switching of o and u exists so words like "gising" (to wake) is pronounced as "giseng" with a strong 'e' and the word "tagu-taguan" (hide-and-go-seek) is pronounced as "tago-tagoan" with a mild 'o'.

Batangas Tagalog boasts the most distinctive accent in Tagalog compared to the more Hispanized northern accents of the language.[citation needed][35] The Batangas accent has been featured in film and television and Filipino actor Leo Martinez speaks with this accent. Martinez's accent, however, will quickly be recognized by native Batangueños as representative of the accent in western Batangas which is milder compared to that used in the eastern part of the province.[citation needed]

Bulacan Tagalog has more deep words and accented like Filipino during the Spanish period.

Quezon and Aurora's Tagalog has unique accents.

Cavite's were a mix of deep Tagalog and Chavacano, a language also spoken in Zamboanga.

Laguna also has a different set of accents.

Nueva Ecija's accent is like Bulacan's, but with different intonations. Tarlac also has this accent.

Code-switching

Taglish and Englog are names given to a mix of English and Tagalog. The amount of English vs. Tagalog varies from the occasional use of English loan words to changing language in mid-sentence. Such code-switching is prevalent throughout the Philippines and in various languages of the Philippines other than Tagalog.

Code-mixing also entails the use of foreign words that are "Filipinized" by reforming them using Filipino rules, such as verb conjugations. Users typically use Filipino or English words, whichever comes to mind first or whichever is easier to use.

- "Magshoshopping kami sa mall. Sino ba ang magdadrive sa shopping center?"

- "We will go shopping at the mall. Who will drive to the shopping center?"

City-dwellers are more likely to do this.

The practice is common in television, radio, and print media as well. Advertisements from companies like Wells Fargo, Wal-Mart, Albertsons, McDonald's, and Western Union have contained Taglish.

Phonology

Tagalog has 33 phonemes: 19 of them are consonants and 14 are vowels. Syllable structure is relatively simple, being maximally consonant-ar-vowel-consonant, where consonant-ar only occurs in borrowed words such as trak "truck" or sombréro "hat".[36]

Vowels

Tagalog has ten simple vowels, five long and five short, and four diphthongs.[36] Before appearing in the area north of Pasig river, Tagalog had three vowel qualities: /a/, /i/, and /u/. This was later expanded to five with the introduction of words from Northern Philippine languages like Kapampangan and Ilocano and Spanish words.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | o̞ ⟨o⟩ | |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ |

/a/ an open central unrounded vowel roughly similar to English "father"; in the middle of a word, a near-open central vowel similar to Received Pronunciation "cup"; or an open front unrounded vowel similar to Received Pronunciation or California English "hat"

/ɛ/ an open-mid front unrounded vowel similar to General American English "bed"

/i/ a close front unrounded vowel similar to English "machine"

/o/ a mid back rounded vowel similar to General American English "soul" or Philippine English "forty"

/u/ a close back rounded vowel similar to English "flute"

Nevertheless, simplification of pairs [o ~ u] and [ɛ ~ i] is likely to take place, especially in some Tagalog as second language, remote location and worker class registers.

The four diphthongs are /aj/, /uj/, /aw/, and /iw/. Long vowels are not written apart from pedagogical texts, where an acute accent is used: á é í ó ú.[36]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Near-close | ɪ ⟨i⟩ | ʊ ⟨u⟩ | |

| Mid | ɛ̝ ⟨e⟩ | o̞ ⟨o⟩ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | |

| Near-open | ɐ ⟨a⟩ | ||

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | ä ⟨a⟩ |

The table above shows all the possible realizations for each of the five vowel sounds depending on the speaker's origin or proficiency. The five general vowels are in bold.

Consonants

Below is a chart of Tagalog consonants. All the stops are unaspirated. The velar nasal occurs in all positions including at the beginning of a word. Loanword variants using these phonemes are italicized inside the angle brackets.

Bilabial | Alveolar/Dental | Post-alveolar/Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nasal | m | n | ɲ ⟨ny, niy⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ||||||

Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ʔ | |||

Affricate | (ts) | tʃ ⟨ts, tiy, ty, ch⟩ | dʒ ⟨diy, dy, j⟩ | |||||||

Fricative | s | ʃ ⟨siy, sy, sh⟩ | x ⟨-k-⟩ | h ⟨h, j⟩ | ||||||

Approximant | l | j ⟨y⟩ | w (ɰ ⟨-g-⟩) | |||||||

Rhotic | ɾ ⟨r⟩ | |||||||||

/k/ between vowels has a tendency to become [x] as in loch, German "Bach", whereas in the initial position it has a tendency to become [kx], especially in the Manila dialect.- Intervocalic /ɡ/ and /k/ tend to become [ɰ], as in Spanish "agua", especially in the Manila dialect.

/ɾ/ and /d/ were once allophones, and they still vary grammatically, with initial /d/ becoming intervocalic /ɾ/ in many words.[36]- A glottal stop that occurs in pausa (before a pause) is omitted when it is in the middle of a phrase,[36] especially in the Metro Manila area. The vowel it follows is then lengthened. However, it is preserved in many other dialects.

- The /ɾ/ phoneme is an alveolar rhotic that has a free variation between a trill, a flap and an approximant ([r~ɾ~ɹ]).

- The /dʒ/ phoneme may become a consonant cluster [dd͡ʒ] in between vowels such as sadyâ [sadˈd͡ʒäʔ].

Glottal stop is not indicated.[36] Glottal stops are most likely to occur when:

- the word starts with a vowel, like "aso" (dog)

- the word includes a dash followed by a vowel, like "mag-aral" (study)

- the word has two vowels next to each other, like "paano" (how)

- the word starts with a prefix followed by a verb that starts with a vowel, like "mag-aayos" ([will] fix)

Lexical stress

Lexical stress, coupled with glottalization, is a distinctive feature in Tagalog. Primary stress normally occurs on either the final or the penultimate syllable of a word. Long vowel accompany primary or secondary stress unless the stress occurs at the end of a word.

Tagalog words are often distinguished from one another by the position of the stress and the presence of the glottal stop. In general, there are four types of phonetic emphases, which, in formal or academic settings, are indicated with a diacritic (tuldík) above the vowel. The penultimate primary stress position (malumay) is the default stress type and so is left unwritten except in dictionaries. The name of each stress type has its corresponding diacritic in the final vowel.

Lexicon | Stressed non-ultimate syllable | Stressed ultimate syllable | Unstressed ultimate syllable with glottal stop | Stressed ultimate syllable with glottal stop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| baka | [ˈbaka] [ˈbaxa] ('cow') | [bɐˈka] [bɐˈxa] ('possible') | ||

| pito | [ˈpito] ('whistle') | [pɪˈto] ('seven') | ||

| kaibigan | [ˈkaʔɪbɪɡan] ('lover') / [kɐɪˈbiɡan] ('friend') | |||

| bayaran | [bɐˈjaran] ('pay [imperative]') | [bɐjɐˈran] ('for hire') | ||

| bata | [ˈbata] ('bath robe') | [bɐˈta] ('persevere') | [ˈbataʔ] ('child') | |

| sala | [ˈsala] ('living room') | [ˈsalaʔ] ('sin') | [sɐˈlaʔ] ('filtered') | |

| baba | [ˈbaba] ('father') | [baˈba] ('piggy back') | [ˈbabaʔ] ('chin') | [bɐˈbaʔ] ('descend [imperative]') |

| labi | [ˈlabɛʔ]/[ˈlabiʔ] ('lips') | [lɐˈbɛʔ]/[lɐˈbiʔ] ('remains') |

Grammar

Writing system

Tagalog, like other Philippines languages today, is written using the Latin alphabet. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish in 1521 and the beginning of their colonization in 1565, Tagalog was written in an abugida–or alphasyllabary—called Baybayin. This system of writing gradually gave way to the use and propagation of the Latin alphabet as introduced by the Spanish. As the Spanish began to record and create grammars and dictionaries for the various languages of the Philippine archipelago, they adopted systems of writing closely following the orthographic customs of the Spanish language and were refined over the years. Until the first half of the 20th century, most Philippine languages were widely written in a variety of ways based on Spanish orthography.

In the late 19th century, a number of educated Filipinos began proposing for revising the spelling system used for Tagalog at the time. In 1884, Filipino doctor and student of languages Trinidad Pardo de Tavera published his study on the ancient Tagalog script Contribucion para el Estudio de los Antiguos Alfabetos Filipinos and in 1887, published his essay El Sanscrito en la lengua Tagalog which made use of a new writing system developed by him. Meanwhile, Jose Rizal, inspired by Pardo de Tavera's 1884 work, also began developing a new system of orthography (unaware at first of Pardo de Tavera's own orthography).[37] A major noticeable change in these proposed orthographies was the use of the letter ⟨k⟩ rather than ⟨c⟩ and ⟨q⟩ to represent the phoneme /k/.

In 1889, the new bilingual Spanish-Tagalog La España Oriental newspaper, of which Isabelo de los Reyes was an editor, began publishing using the new orthography stating in a footnote that it would "use the orthography recently introduced by ... learned Orientalis". This new orthography, while having its supporters, was also not initially accepted by several writers. Soon after the first issue of La España, Pascual H. Poblete's Revista Católica de Filipina began a series of articles attacking the new orthography and its proponents. A fellow writer, Pablo Tecson was also critical. Among the attacks was the use of the letters "k" and "w" as they were deemed to be of German origin and thus its proponents were deemed as "unpatriotic". The publishers of these two papers would eventually merge as La Lectura Popular in January 1890 and would eventually make use of both spelling systems in its articles.[38][37] Pedro Laktaw, a schoolteacher, published the first Spanish-Tagalog dictionary using the new orthography in 1890.[38]

In April 1890, Jose Rizal authored an article Sobre la Nueva Ortografia de la Lengua Tagalog in the Madrid-based periodical La Solidaridad. In it, he addressed the criticisms of the new writing system by writers like Pobrete and Tecson and the simplicity, in his opinion, of the new orthography. Rizal described the orthography promoted by Pardo de Tavera as "more perfect" than what he himself had developed.[38] The new orthography was however not broadly adopted initially and was used inconsistently in the bilingual periodicals of Manila until the early 20th century.[38] The revolutionary society Kataás-taasan, Kagalang-galang Katipunan ng̃ mg̃á Anak ng̃ Bayan or Katipunan made use of the k-orthography and the letter k featured prominently on many of its flags and insignias.[38]

In 1937, Tagalog was selected to serve as basis for the country's national language. In 1940, the Balarílà ng Wikang Pambansâ (English: Grammar of the National Language) of grammarian Lope K. Santos introduced the Abakada alphabet. This alphabet consists of 20 letters and became the standard alphabet of the national language.[39] The orthography as used by Tagalog would eventually influence and spread to the systems of writing used by other Philippine languages (which had been using variants of the Spanish-based system of writing). In 1987, the ABAKADA was dropped and in its place is the expanded Filipino alphabet.

Baybayin

Tagalog was written in an abugida—or alphasyllabary—called Baybayin prior to the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines, in the 16th century. This particular writing system was composed of symbols representing three vowels and 14 consonants. Belonging to the Brahmic family of scripts, it shares similarities with the Old Kawi script of Java and is believed to be descended from the script used by the Bugis in Sulawesi.

Although it enjoyed a relatively high level of literacy, Baybayin gradually fell into disuse in favor of the Latin alphabet taught by the Spaniards during their rule.

There has been confusion of how to use Baybayin, which is actually an abugida, or an alphasyllabary, rather than an alphabet. Not every letter in the Latin alphabet is represented with one of those in the Baybayin alphasyllabary. Rather than letters being put together to make sounds as in Western languages, Baybayin uses symbols to represent syllables.

A "kudlit" resembling an apostrophe is used above or below a symbol to change the vowel sound after its consonant. If the kudlit is used above, the vowel is an "E" or "I" sound. If the kudlit is used below, the vowel is an "O" or "U" sound. A special kudlit was later added by Spanish missionaries in which a cross placed below the symbol to get rid of the vowel sound all together, leaving a consonant. Previously, the consonant without a following vowel was simply left out (for example, bundok being rendered as budo), forcing the reader to use context when reading such words.

Example:

Baybayin is encoded in Unicode version 3.2 in the range 1700-171F under the name "Tagalog".

vowels

| b

| k

| d/r

| g

| h

| l

| m

| n

| ng

| p

| s

| t

| w

| y

|

Latin alphabet

Abecedario

Until the first half of the 20th century, Tagalog was widely written in a variety of ways based on Spanish orthography consisting of 32 letters called 'ABECEDARIO' (Spanish for "alphabet"):[40][41]

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | Ng | ng |

| B | b | Ñ | ñ |

| C | c | N͠g / Ñg | n͠g / ñg |

| Ch | ch | O | o |

| D | d | P | p |

| E | e | Q | q |

| F | f | R | r |

| G | g | Rr | rr |

| H | h | S | s |

| I | i | T | t |

| J | j | U | u |

| K | k | V | v |

| L | l | W | w |

| Ll | ll | X | x |

| M | m | Y | y |

| N | n | Z | z |

Abakada

When the national language was based on Tagalog, grammarian Lope K. Santos introduced a new alphabet consisting of 20 letters called ABAKADA in school grammar books called balarilà:[42][43][44]

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | N | n |

| B | b | Ng | ng |

| K | k | O | o |

| D | d | P | p |

| E | e | R | r |

| G | g | S | s |

| H | h | T | t |

| I | i | U | u |

| L | l | W | w |

| M | m | Y | y |

Revised alphabet

In 1987, the Department of Education, Culture and Sports issued a memo stating that the Philippine alphabet had changed from the Pilipino-Tagalog Abakada version to a new 28-letter alphabet[45][46] to make room for loans, especially family names from Spanish and English:[47]

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | Ñ | ñ |

| B | b | Ng | ng |

| C | c | O | o |

| D | d | P | p |

| E | e | Q | q |

| F | f | R | r |

| G | g | S | s |

| H | h | T | t |

| I | i | U | u |

| J | j | V | v |

| K | k | W | w |

| L | l | X | x |

| M | m | Y | y |

| N | n | Z | z |

ng and mga

The genitive marker ng and the plural marker mga (e.g. Iyan ang mga damit ko. (Those are my clothes)) are abbreviations that are pronounced nang [naŋ] and mangá [mɐˈŋa]. Ng, in most cases, roughly translates to "of" (ex. Siya ay kapatid ng nanay ko. She is the sibling of my mother) while nang usually means "when" or can describe how something is done or to what extent (equivalent to the suffix -ly in English adverbs), among other uses.

Nang si Hudas ay nadulás.—When Judas slipped.

Gumising siya nang maaga.—He woke up early.

Gumalíng nang todo si Juan dahil nag-ensayo siya.—Juan greatly improved because he practiced.

In the first example, nang is used in lieu of the word noong (when; Noong si Hudas ay madulas). In the second, nang describes that the person woke up (gumising) early (maaga); gumising nang maaga. In the third, nang described up to what extent that Juan improved (gumaling), which is "greatly" (nang todo). In the latter two examples, the ligature na and its variants -ng and -g may also be used (Gumising na maaga/Maagang gumising; Gumaling na todo/Todong gumaling).

The longer nang may also have other uses, such as a ligature that joins a repeated word:

Naghintáy sila nang naghintáy.—They kept on waiting" (a closer calque: "They were waiting and waiting.")

pô/hô and opò/ohò

The words pô/hô and opò/ohò are traditionally used as polite iterations of the affirmative "oo" ("yes"). It is generally used when addressing elders or superiors such as bosses or teachers.

"Pô" and "opò" are specifically used to denote a high level of respect when addressing older persons of close affinity like parents, relatives, teachers and family friends. "Hô" and "ohò" are generally used to politely address older neighbours, strangers, public officials, bosses and nannies, and may suggest a distance in societal relationship and respect determined by the addressee's social rank and not their age. However, "pô" and "opò" can be used in any case in order to express an elevation of respect.

- Example: "Pakitapon naman pô/ho yung basura." ("Please throw away the trash.")

Used in the affirmative:

- Ex: "Gutóm ka na ba?" "Opò/Ohò". ("Are you hungry yet?" "Yes.")

Pô/Hô may also be used in negation.

- Ex: "Hindi ko pô/hô alam 'yan." ("I don't know that.")

Vocabulary and borrowed words

A 3D pie-chart about the languages and loanwords that comprise the Tagalog language.

Tagalog vocabulary is composed mostly of words of native Austronesian origin - most of the words that end with the diphthongs -iw, (e.g. saliw) and those words that exhibit reduplication (e.g. halo-halo, patpat, etc.). However it has a significant number of Spanish loanwords. Spanish is the language that has bequeathed the most loanwords to Tagalog.

Tagalog also includes many loanwords from English, Indian languages (Sanskrit and Tamil), Chinese languages (Hokkien, Cantonese, Mandarin), Japanese, Arabic and Persian.

Due to trade with Mexico via the Manila galleons from the 16th to the 19th centuries, many words from Nahuatl were introduced to Tagalog, but some of them were replaced by Spanish loanwords in the latter part of the Spanish colonization in the islands.

The Philippines has long been a melting pot of nations. The islands have been subject to different influences and a meeting point of numerous migrations since the early prehistoric origins of trading activities, especially from the time of the Neolithic Period, Silk Road, Tang Dynasty, Ming Dynasty, Ryukyu Kingdom and Manila Galleon trading periods. This means that the evolution of the language is difficult to reconstruct (although many theories exist).

In pre-Hispanic times, Trade Malay was widely known and spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia.

English has borrowed some words from Tagalog, such as abaca, barong, balisong, boondocks, jeepney, Manila hemp, pancit, ylang-ylang, and yaya, although the vast majority of these borrowed words are only used in the Philippines as part of the vocabularies of Philippine English.[citation needed]

| Example | Definition |

|---|---|

boondocks | meaning "rural" or "back country," was imported by American soldiers stationed in the Philippines following the Spanish–American War as a mispronounced version of the Tagalog bundok, which means "mountain." |

| cogon | a type of grass, used for thatching. This word came from the Tagalog word kugon (a species of tall grass). |

ylang-ylang | a tree whose fragrant flowers are used in perfumes. |

Abaca | a type of hemp fiber made from a plant in the banana family, from abaká. |

Manila hemp | a light brown cardboard material used for folders and paper usually made from abaca hemp. |

Capiz | also known as window oyster, is used to make windows. |

Tagalog has contributed several words to Philippine Spanish, like barangay (from balan͠gay, meaning barrio), the abacá, cogon, palay, dalaga etc.

Tagalog words of foreign origin

Cognates with other Philippine languages

| Tagalog word | meaning | language of origin | original spelling |

|---|---|---|---|

| bakit | why | Kapampangan | obakit |

| akyat | climb/step up | Kapampangan | ukyát/mukyat |

| at | and | Kapampangan | at |

| bundok | mountain | Kapampangan | bunduk |

| huwag | don't | Pangasinan | ag |

| aso | dog | South Cordilleran or Ilocano (also Ilokano) | aso |

| tayo | we (inc.) | South Cordilleran or Ilocano | tayo |

| ito, nito | this, its | South Cordilleran or Ilocano | to |

| ng | of | Cebuano Hiligaynon Waray Kapampangan Pangasinan Ilocano | sa sg (pronounced as /sang/) han ning na nga |

| araw | sun; day | Visayan languages | adlaw |

| ang | definite article | Visayan languages Central Bikol | ang an |

Austronesian comparison chart

Below is a chart of Tagalog and a number of other Austronesian languages comparing thirteen words.

| English | one | two | three | four | person | house | dog | coconut | day | new | we (inclusive) | what | fire |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tagalog | isa | dalawa | tatlo | apat | tao | bahay | aso | niyog | araw | bago | tayo | ano | apoy |

Tombulu (Minahasa) | esa | zua (rua) | telu | epat | tou | walé | asu | po'po' | endo | weru | kai, kita | apa | api |

Central Bikol | saro | duwa | tulo | apat | tawo | harong | ayam | niyog | aldaw | ba-go | kita | ano | kalayo |

Rinconada Bikol | əsad | darwā | tolō | əpat | tawō | baləy | ayam | noyog | aldəw | bāgo | kitā | onō | kalayō |

Waray | usa | duha | tulo | upat | tawo | balay | ayam/ido | lubi | adlaw | bag-o | kita | anu | kalayo |

Cebuano | usa/isa | duha | tulo | upat | tawo | balay | iro | lubi | adlaw | bag-o | kita | unsa | kalayo |

Hiligaynon | isa | duha | tatlo | apat | tawo | balay | ido | lubi | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kalayo |

Aklanon | isaea, sambilog, uno | daywa, dos | tatlo, tres | ap-at, kwatro | tawo | baeay | ayam | niyog | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kaeayo |

Kinaray-a | sara | darwa | tatlo | apat | tawo | balay | ayam | niyog | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kalayo |

Tausug | hambuuk | duwa | tu | upat | tau | bay | iru' | niyug | adlaw | ba-gu | kitaniyu | unu | kayu |

Maranao | isa | dowa | t'lo | phat | taw | walay | aso | neyog | gawi'e | bago | tano | tonaa | apoy |

Kapampangan | metung | adwa | atlu | apat | tau | bale | asu | ngungut | aldo | bayu | ikatamu | nanu | api |

Pangasinan | sakey | dua, duara | talo, talora | apat, apatira | too | abong | aso | niyog | ageo | balo | sikatayo | anto | pool |

Ilocano | maysa | dua | tallo | uppat | tao | balay | aso | niog | aldaw | baro | datayo | ania | apoy |

Ivatan | asa | dadowa | tatdo | apat | tao | vahay | chito | niyoy | araw | va-yo | yaten | ango | apoy |

Ibanag | tadday | dua | tallu | appa' | tolay | balay | kitu | niuk | aggaw | bagu | sittam | anni | afi |

Yogad | tata | addu | tallu | appat | tolay | binalay | atu | iyyog | agaw | bagu | sikitam | gani | afuy |

Gaddang | antet | addwa | tallo | appat | tolay | balay | atu | ayog | aw | bawu | ikkanetam | sanenay | afuy |

Tboli | sotu | lewu | tlu | fat | tau | gunu | ohu | lefo | kdaw | lomi | tekuy | tedu | ofih |

Kadazan | iso | duvo | tohu | apat | tuhun | hamin | tasu | piasau | tadau | vagu | tokou | onu | tapui |

Malaysian | satu | dua | tiga | empat | orang | rumah | anjing | kelapa/ nyior | hari | baru/ baharu | kita | apa | api |

Indonesian | satu | dua | tiga | empat | orang | rumah/balai | anjing | kelapa/nyiur | hari | baru | kita | apa/anu | api |

Javanese | siji | loro | telu | papat | uwong | omah | asu | klapa/kambil | hari | anyar/enggal | kita | apa/anu | geni |

Acehnese | sa | duwa | lhèë | peuët | ureuëng | rumoh/balèë | asèë | u | uroë | barô | (geu)tanyoë | peuë | apuy |

Lampung | sai | khua | telu | pak | jelema | lamban | asu | nyiwi | khani | baru | kham | api | apui |

Buginese | se'di | dua | tellu | eppa' | tau | bola | asu | kaluku | esso | baru | idi' | aga | api |

Batak | sada | dua | tolu | opat | halak | jabu | biang | harambiri | ari | baru | hita | aha | api |

Tetum | ida | rua | tolu | haat | ema | uma | asu | nuu | loron | foun | ita | saida | ahi |

Maori | tahi | rua | toru | wha | tangata | whare | kuri | kokonati | ra | hou | taua | aha | ahi |

Tuvaluan | tasi | lua | tolu | fá | toko | fale | kuri | moku | aso | fou | tāua | ā | afi |

Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | kanaka | hale | 'īlio | niu | ao | hou | kākou | aha | ahi |

Banjarese | asa | dua | talu | ampat | urang | rumah | hadupan | kalapa | hari | hanyar | kita | apa | api |

Malagasy | isa | roa | telo | efatra | olona | trano | alika | voanio | andro | vaovao | isika | inona | afo |

Dusun | iso | duo | tolu | apat | tulun | walai | tasu | piasau | tadau | wagu | tokou | onu/nu | tapui |

Iban | sa/san | duan | dangku | dangkan | orang | rumah | ukui/uduk | nyiur | hari | baru | kitai | nama | api |

Melanau | satu | dua | telou | empat | apah | lebok | asou | nyior | lau | baew | teleu | nama | apui |

Religious literature

Religious literature remains one of the most dynamic contributors to Tagalog literature. The first Bible in Tagalog, then called Ang Biblia[48] ("the Bible") and now called Ang Dating Biblia[49] ("the Old Bible"), was published in 1905. In 1970, the Philippine Bible Society translated the Bible into modern Tagalog. Even before the Second Vatican Council, devotional materials in Tagalog had been in circulation. There are at least four circulating Tagalog translations of the Bible

- the Magandang Balita Biblia (a parallel translation of the Good News Bible), which is the ecumenical version

- the Bibliya ng Sambayanang Pilipino

- the 1905 Ang Biblia is a more Protestant version

- the Bagong Sanlibutang Salin ng Banal na Kasulatan (New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures)

When the Second Vatican Council, (specifically the Sacrosanctum Concilium) permitted the universal prayers to be translated into vernacular languages, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines was one of the first to translate the Roman Missal into Tagalog. The Roman Missal in Tagalog was published as early as 1982.

Jehovah's Witnesses were printing Tagalog literature at least as early as 1941[50] and The Watchtower (the primary magazine of Jehovah's Witnesses) has been published in Tagalog since at least the 1950s. New releases are now regularly released simultaneously in a number of languages, including Tagalog. The official website of Jehovah's Witnesses also has some publications available online in Tagalog.[51]

Tagalog is quite a stable language, and very few revisions have been made to Catholic Bible translations. Also, as Protestantism in the Philippines is relatively young, liturgical prayers tend to be more ecumenical.

Examples

Lord's Prayer

In Tagalog, the Lord's Prayer is exclusively known by its incipit, Amá Namin (literally, "Our Father").

Amá namin, sumasalangit Ka

Sambahín ang ngalan Mo.

Mapasaamin ang kaharián Mo.

Sundín ang loób Mo,

Dito sa lupà, gaya nang sa langit.

Bigyán Mo kamí ngayón ng aming kakanin sa araw-araw,

At patawarin Mo kamí sa aming mga salâ,

Para nang pagpápatawad namin,

Sa nagkakasalà sa amin;

At huwág Mo kamíng ipahintulot sa tuksó,

At iadyâ Mo kamí sa lahát ng masamâ.

[Sapagkát sa Inyó ang kaharián, at ang kapangyarihan,

At ang kaluwálhatian, ngayón, at magpakailanman.]

Amen

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

This is Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Pángkalahatáng Pagpapahayag ng Karapatáng Pantao)

Bawat tao'y isinilang na may layà at magkakapantáy ang tagláy na dangál at karapatán. Silá'y pinagkalooban ng pangangatwiran at budhî na kailangang gamitin nilá sa pagtuturingan nilá sa diwà ng pagkakapatiran.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[52]

Numbers

The numbers (mga numero) in Tagalog language are of two sets. The first set consists of native Tagalog words and the other set are Spanish loanwords. (This may be compared to other East Asian languages, except with the second set of numbers borrowed from Spanish instead of Chinese.) For example, when a person refers to the number "seven", it can be translated into Tagalog as "pito" or "syete" (Spanish: siete).

| Number | Cardinal | Spanish loanword (Original Spanish) | Ordinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | sero / walâ (lit. "null") / bokyà | sero (cero) | - |

| 1 | isá | uno (uno) | una |

| 2 | dalawá [dalaua] | dos (dos) | pangalawá / ikalawá (informally, ikadalawá) |

| 3 | tatló | tres (tres) | pangatló / ikatló |

| 4 | apat | kuwatro (cuatro) | pang-apat / ikaapat ("ika" and the number-word are never hyphenated. For numbers, however, they always are.) |

| 5 | limá | singko (cinco) | panlimá / ikalimá |

| 6 | anim | sais (seis) | pang-anim / ikaanim |

| 7 | pitó | siyete (siete) | pampitó / ikapitó |

| 8 | waló | otso (ocho) | pangwaló / ikawaló |

| 9 | siyám | nuwebe (nueve) | pansiyám / ikasiyám |

| 10 | sampû [sang puo] | diyés (diez) | pansampû / ikasampû (or ikapû in some literary compositions) |

| 11 | labíng-isá | onse (once) | panlabíng-isá / pang-onse / ikalabíng-isá |

| 12 | labíndalawá | dose (doce) | panlabíndalawá / pandose / ikalabíndalawá |

| 13 | labíntatló | trese (trece) | panlabíntatló / pantrese / ikalabíntatló |

| 14 | labíng-apat | katorse (catorce) | panlabíng-apat / pangkatorse / ikalabíng-apat |

| 15 | labínlimá | kinse (quince) | panlabínlimá / pangkinse / ikalabínlimá |

| 16 | labíng-anim | disisaís (dieciséis) | panlabíng-anim / pandyes-sais / ikalabíng-anim |

| 17 | labímpitó | disisyete (diecisiete) | panlabímpitó / pandyes-syete / ikalabímpitó |

| 18 | labíngwaló | disiotso (dieciocho) | panlabíngwaló / pandyes-otso / ikalabíngwaló |

| 19 | labinsiyám | disinuwebe (diecinueve) | panlabinsiyám / pandyes-nwebe / ikalabinsiyám |

| 20 | dalawampû | bente / beinte (veinte) | pandalawampû / ikadalawampû (rare literary variant: ikalawampû) |

| 21 | dalawampú't isá | bente'y uno (veintiuno) | pang-dalawampú't isá / ikalawamapú't isá |

| 30 | tatlumpû | trenta / treinta (treinta) | pantatlumpû / ikatatlumpû (rare literary variant: ikatlumpû) |

| 40 | apatnapû | kuwarenta (cuarenta) | pang-apatnapû / ikaapatnapû |

| 50 | limampû | singkuwenta (cincuenta) | panlimampû / ikalimampû |

| 60 | animnapû | sesenta (sesenta) | pang-animnapû / ikaanimnapû |

| 70 | pitumpû | setenta (setenta) | pampitumpû / ikapitumpû |

| 80 | walumpû | otsenta / utsenta (ochenta) | pangwalumpû / ikawalumpû |

| 90 | siyamnapû | nobenta (noventa) | pansiyamnapû / ikasiyamnapû |

| 100 | sándaán | siyento (cien) | pan(g)-(i)sándaán / ikasándaán (rare literary variant: ika-isándaan) |

| 200 | dalawandaán | dos siyentos (doscientos) | pandalawándaán / ikadalawandaan (rare literary variant: ikalawándaán) |

| 300 | tatlóndaán | tres siyentos (trescientos) | pantatlóndaán / ikatatlondaan (rare literary variant: ikatlóndaán) |

| 400 | apat na raán | kuwatro siyentos (cuatrocientos) | pang-apat na raán / ikaapat na raán |

| 500 | limándaán | kinyentos (quinientos) | panlimándaán / ikalimándaán |

| 600 | anim na raán | sais siyentos (seiscientos) | pang-anim na raán / ikaanim na raán |

| 700 | pitondaán | siyete siyentos (sietecientos) | pampitóndaán / ikapitóndaán (or ikapitóng raán) |

| 800 | walóndaán | otso siyentos (ochocientos) | pangwalóndaán / ikawalóndaán (or ikawalóng raán) |

| 900 | siyám na raán | nuwebe siyentos (novecientos) | pansiyám na raán / ikasiyám na raán |

| 1,000 | sánlibo | mil (mil) | pan(g)-(i)sánlibo / ikasánlibo |

| 2,000 | dalawánlibo | dos mil (dos mil) | pangalawáng libo / ikalawánlibo |

| 10,000 | sánlaksâ / sampúng libo | diyes mil (diez mil) | pansampúng libo / ikasampúng libo |

| 20,000 | dalawanlaksâ / dalawampúng libo | bente mil (veinte mil) | pangalawampúng libo / ikalawampúng libo |

| 100,000 | sangyutá / sandaáng libo | siyento mil (cien mil) | |

| 200,000 | dalawangyutá / dalawandaáng libo | dos siyento mil (dos cientos mil) | |

| 1,000,000 | sang-angaw / sangmilyón | milyón (un millón) | |

| 2,000,000 | dalawang-angaw / dalawang milyón | dos milyón (dos millones) | |

| 10,000,000 | sangkatì / sampung milyón | dyes milyón (diez millones) | |

| 100,000,000 | sampúngkatì / sandaáng milyón | syento milyón (cien millones) | |

| 1,000,000,000 | sang-atos / sambilyón | bilyón (un billón) | |

| 1,000,000,000,000 | sang-ipaw / santrilyón | trilyón (un trillón) | |

| Number | English | Ordinal Spanish | Cardinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | first | primero/a | una / ika-isá |

| 2nd | second | segundo/a | ikalawá |

| 3rd | third | tercero/a | ikatló |

| 4th | fourth | cuarto/a | ika-apat |

| 5th | fifth | quinto/a | ikalimá |

| 6th | sixth | sexto/a | ika-anim |

| 7th | seventh | séptimo/a | ikapitó |

| 8th | eighth | octavo/a | ikawaló |

| 9th | ninth | noveno/a | ikasiyám |

| 10th | tenth | décimo/a | ikasampû |

| 1/2 | half | media | kalahatì |

| 1/4 | quarter | cuarta | kapat |

| 3/5 | three-fifths | tres quintas partes | tatlóng-kalimá |

| 2/3 | two-thirds | dos tercios | dalawáng-katló |

| 1 1/2 | one and a half | un medio | isá't kalahatì |

| 2 2/3 | two and two-thirds | dos de dos tercios | dalawá't dalawáng-katló |

| 0.5 | zero point five | cero punto cinco | salapî / limá hinatì sa sampû |

| 0.005 | zero point zero zero five | cero punto cero cero cinco | bagól / limá hinatì sa sanlibo |

| 1.25 | one point twenty-five | uno punto veinticinco | isá't dalawampú't limá hinatì sa sampû |

| 2.025 | two point zero twenty-five | dos punto cero veinticinco | dalawá't dalawampú't limá hinatì sa sanlibo |

| 25% | twenty-five percent | veinticinco por ciento | dalawampú't-limáng bahagdán |

| 50% | fifty percent | cincuenta por ciento | limampúng bahagdán |

| 75% | seventy-five percent | setenta y cinco por ciento | pitumpú't-limáng bahagdán |

Months and days

Months and days in Tagalog are also localised forms of Spanish months and days. "Month" in Tagalog is buwán (also the word for moon) and "day" is araw (the word also means sun). Unlike Spanish, however, months and days in Tagalog are always capitalised.

| Month | Original Spanish | Tagalog (abbreviation) |

|---|---|---|

| January | enero | Enero (Ene.) |

| February | febrero | Pebrero (Peb.) |

| March | marzo | Marso (Mar.) |

| April | abril | Abríl (Abr.) |

| May | mayo | Mayo (Mayo) |

| June | junio | Hunyo (Hun.) |

| July | julio | Hulyo (Hul.) |

| August | agosto | Agosto (Ago.) |

| September | septiembre | Septyembre (Sept.) |

| October | octubre | Oktubre (Okt.) |

| November | noviembre | Nobyembre (Nob.) |

| December | diciembre | Disyembre (Dis.) |

| Day | Original Spanish | Tagalog |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | lunes | Lunes |

| Tuesday | martes | Martes |

| Wednesday | miércoles | Miyérkules / Myérkules |

| Thursday | jueves | Huwebes / Hwebes |

| Friday | viernes | Biyernes / Byernes |

| Saturday | sábado | Sábado |

| Sunday | domingo | Linggó |

Time

Time expressions in Tagalog are also Tagalized forms of the corresponding Spanish. "Time" in Tagalog is panahon, or more commonly oras. Unlike Spanish and English, times in Tagalog are capitalized whenever they appear in a sentence.

| Time | English | Original Spanish | Tagalog |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hour | one hour | una hora | Isang oras |

| 2 min | two minutes | dos minutos | Dalawang sandali/minuto |

| 3 sec | three seconds | tres segundos | Tatlong saglit/segundo |

| morning | mañana | Umaga | |

| afternoon | tarde | Hapon | |

| evening/night | noche | Gabi | |

| noon | mediodía | Tanghali | |

| midnight | medianoche | Hatinggabi | |

| 1:00 am | one in the morning | una de la mañana | Ika-isa ng umaga |

| 7:00 pm | seven at night | siete de la noche | Ikapito ng gabi |

| 1:15 | quarter past one quarter after one one-fifteen | una y cuarto | Kapat makalipas ikaisa Labinlima makalipas ikaisa Apatnapu't-lima bago mag-ikaisa |

| 2:30 | half past two two-thirty | dos y media | Kalahati makalipas ikalawa Tatlumpu makalipas ikalawa |

| 3:45 | three-forty-five quarter to/of four | tres y cuarenta y cinco | Tatlong-kapat makalipas ikatlo Apatnapu't-lima makalipas ikatlo Labinlima bago mag-ikaapat |

| 4:25 | four-twenty-five | cuatro y veinticinco | Dalawampu't-lima makalipas ikaapat Tatlumpu't-lima bago mag-ikaapat |

| 5:35 | five-thirty-five twenty-five to/of six | cinco y treinta y cinco | Tatlumpu't-lima makalipas ikalima Dalawampu't-lima bago mag-ikaanim |

Common phrases

| English | Tagalog (with Pronunciation) |

|---|---|

| Filipino | Pilipino [ˌpiːliˈpiːno] |

| English | Inglés [ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs] |

| Tagalog | Tagalog [tɐˈɡaːloɡ] |

| Spanish | "Espanyol/Español" |

| What is your name? | Anó ang pangalan ninyo/nila*? (plural or polite) [ɐˈno aŋ pɐˈŋaːlan nɪnˈjo], Anó ang pangalan mo? (singular) [ɐˈno aŋ pɐˈŋaːlan mo] |

| How are you? | kumustá [kʊmʊsˈta] (modern), Anó po áng lagáy ninyo/nila? (old use) |

| Good morning! | Magandáng umaga! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ uˈmaːɡa] |

| Good noontime! (from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.) | Magandáng tanghali! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ taŋˈhaːlɛ] |

| Good afternoon! (from 1 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.) | Magandáng hapon! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ˈhaːpon] |

| Good evening! | Magandáng gabí! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ɡɐˈbɛ] |

| Good-bye | paálam [pɐˈʔaːlam] |

| Please | Depending on the nature of the verb, either pakí- [pɐˈki] or makí- [mɐˈki] is attached as a prefix to a verb. ngâ [ŋaʔ] is optionally added after the verb to increase politeness. (e.g. Pakipasa ngâ ang tinapay. ("Can you pass the bread, please?")) |

| Thank you | Salamat [sɐˈlaːmat] |

| This one | ito [ʔiˈtoh], sometimes pronounced [ʔɛˈtoh] (literally—"it", "this") |

| That one | iyan [ʔiˈjan], When pointing to something at greater distances: iyun [ʔiˈjʊn] or iyon [ʔiˈjon] |

| Here | dito [dɪˈtoh], heto [hɛˈtoh] ("Here it is") |

| There | doon [dʒan], hayan [hɑˈjan] ("There it is") |

| How much? | Magkano? [mɐɡˈkaːno] |

| Yes | oo [ˈoːʔo] opô [ˈʔopoʔ] or ohô [ˈʔohoʔ] (formal/polite form) |

| No | hindî [hɪnˈdɛʔ], often shortened to dî [dɛʔ] hindî pô (formal/polite form) |

| I don't know | hindî ko álam [hɪnˈdɛʔ ko aːlam] Very informal: ewan [ʔɛˈʊɑn], archaic aywan [ɑjˈʊɑn] (closest English equivalent: colloquial dismissive 'Whatever') |

| Sorry | pasensya pô (literally from the word "patience") or paumanhin po [pɐˈsɛːnʃa poʔ] patawad po [pɐtaːwad poʔ] (literally—"asking your forgiveness") |

| Because | kasí [kɐˈsɛ] or dahil [dɑˈhɪl] |

| Hurry! | dalí! [dɐˈli], bilís! [bɪˈlis] |

| Again | mulí [muˈli], ulít [ʊˈlɛt] |

| I don't understand | Hindî ko naiintindihan [hɪnˈdiː ko nɐʔɪɪnˌtɪndiˈhan] or Hindi ko nauunawaan [hɪnˈdiː ko nɐʔʊʊnawaʔˌʔan] |

| What? | Anó? [ɐˈno] |

| Where? | Saán? [sɐˈʔan], Nasaán? [ˌnaːsɐˈʔan] (literally - "Where at?") |

| Why? | Bakít? [bɑˈkɛt] |

| When? | Kailan? [kɑjˈlɑn], [kɑˈɪˈlɑn], or [kɛˈlɑn] (literally—"In what order?/"At what count?"") |

| How? | Paánó? [pɑˌɐˈno] (literally—"By what?") |

| Where's the bathroom? | Nasaán ang banyo? [ˌnaːsɐˈʔan ʔaŋ ˈbaːnjo] |

| Generic toast | Mabuhay! [mɐˈbuːhaɪ] (literally—"long live") |

| Do you speak English? | Marunong ka bang magsalitâ ng Ingglés? [mɐˈɾuːnoŋ ka baŋ mɐɡsaliˈtaː naŋ ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs] Marunong po ba kayong magsalitâ ng Ingglés? (polite version for elders and strangers) |

| It is fun to live. | Masaya ang mabuhay! [mɐˈsaˈja ʔaŋ mɐˈbuːhaɪ] or Masaya'ng mabuhay (contracted version) |

*Pronouns such as niyo (2nd person plural) and nila (3rd person plural) are used on a single 2nd person in polite or formal language. See Tagalog grammar.

Proverbs

Ang hindî marunong lumingón sa pinánggalingan ay hindî makaráratíng sa paroroonan. (José Rizal)

One who knows not how to look back from whence he came, will never get to where he is going.

Tao ka nang humarap, bilang tao kitang haharapin.

(A proverb in Southern Tagalog that made people aware the significance of sincerity in Tagalog communities. It says, "As a human you reach me, I treat you as a human and never act as a traitor.")

Hulí man daw at magalíng, nakákahábol pa rin. (Hulí man raw at magalíng, nakákahabol pa rin.)

If one is behind but capable, one will still be able to catch up.

Magbirô ka na sa lasíng, huwág lang sa bagong gising.

Make fun of someone drunk, if you must, but never one who has just awakened.

Aanhín pa ang damó kung patáy na ang kabayo?

What use is the grass if the horse is already dead?

Ang sakít ng kalingkingan, ramdám ng buóng katawán.

The pain in the pinkie is felt by the whole body.

(In a group, if one goes down, the rest follow.)

Nasa hulí ang pagsisisi.

Regret is always in the end.

Pagkáhabà-habà man ng prusisyón, sa simbahan pa rin ang tulóy.

The procession may stretch on and on, but it still ends up at the church.

(In romance: refers to how certain people are destined to be married. In general: refers to how some things are inevitable, no matter how long you try and postpone it.)

Kung 'dî mádaán sa santóng dasalan, daanin sa santóng paspasan.

If it cannot be got through holy prayer, get it through blessed force.

(In romance and courting: santóng paspasan literally means 'holy speeding' and is a euphemism for sexual intercourse. It refers to the two styles of courting by Filipino boys: one is the traditional, protracted, restrained manner favoured by older generations, which often featured serenades and manual labour for the girl's parents; the other is upfront seduction, which may lead to a slap on the face or a pregnancy out of wedlock. The second conclusion is known as pikot or what Western cultures would call a 'shotgun marriage'. This proverb is also applied in terms of diplomacy and negotiation.)

Majority provinces

Northern Tagalog

- Central Luzon Region

- Bataan

- Bulacan

- Nueva Ecija

- Zambales

- (including Aurora)

Central Tagalog

- National Capital Region

Metro Manila (commonly, Taglish) (mixed with other languages, officially Filipino language)- (including Rizal)

Southern Tagalog

- Southern Luzon

(mainly) Calabarzon and Mimaropa

- Batangas

- Cavite

- Laguna

- Marinduque

- Occidental Mindoro

- Oriental Mindoro

- Quezon

- Romblon

- (including Palawan)

- (including Camarines Norte; outside jurisdiction from (Bicol Region))

See also

- Abakada alphabet

- Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino

- Filipino alphabet

- Old Tagalog

- Filipino orthography

- Tagalog Wikipedia

References

^ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

^ Filipino at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

^ Resulta mula sa 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Educational Characteristics of the Filipinos, National Statistics Office, 18 March 2005, archived from the original on 27 January 2008.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Tagalogic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Tagalog/Filipino". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

^ According to the OED and Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

^ [1]

^ [2]

^ Zorc, David. 1977. "The Bisayan Dialects of the Philippines: Subgrouping and Reconstruction". Pacific Linguistics C.44. Canberra: The Australian National University

^ Blust, Robert. 1991. "The Greater Central Philippines hypothesis". Oceanic Linguistics 30:73–129

^ Juan José de Noceda, Pedro de Sanlucar, Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala, Manila 2013, pg iv, Komision sa Wikang Filipino

^ Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala, Manila 1860 at Google Books

^ Juan José de Noceda, Pedro de Sanlucar, Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 2013, Komision sa Wikang Filipino.

^ Spieker-Salazar, Marlies (1992). "A contribution to Asian Historiography : European studies of Philippines languages from the 17th to the 20th century". Archipel. 44 (1): 183–202. doi:10.3406/arch.1992.2861.

^ Cruz, H. (1906). Kun sino ang kumathâ ng̃ "Florante": kasaysayan ng̃ búhay ni Francisco Baltazar at pag-uulat nang kanyang karunung̃a't kadakilaan. Libr. "Manila Filatélico,". Retrieved January 8, 2017.

^ 1897 Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Article VIII, Filipiniana.net, archived from the original on 2009-02-28, retrieved 2008-01-16

^ 1935 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Section 3, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

^ abc Manuel L. Quezon III, Quezon’s speech proclaiming Tagalog the basis of the National Language (PDF), quezon.ph, retrieved 2010-03-26

^ abcde Andrew Gonzalez (1998), "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF), Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 19 (5, 6): 487–488, doi:10.1080/01434639808666365, retrieved 2007-03-24.

^ 1973 Philippine Constitution, Article XV, Sections 2–3, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

^ "Mga Probisyong Pangwika sa Saligang-Batas". Wika.pbworks.com. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

^ "What the PH constitutions say about the national language". Rappler.

^ "The cost of being tongue-tied in the colonisers' tongue". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2018.ONCE it claimed to have more English speakers than all but two other countries, and it has exported millions of them. But these days Filipinos are less boastful. Three decades of decline in the share of Filipinos who speak the language, and the deteriorating proficiency of those who can manage some English, have eroded one of the country's advantages in the global economy. Call-centres complain that they reject nine-tenths of otherwise qualified job applicants, mostly college graduates, because of their poor command of English. This is lowering the chances that the outsourcing industry will succeed in its effort to employ close to 1m people, account for 8.5% of GDP and have 10% of the world market

^ "Filipino Language in the Curriculum - National Commission for Culture and the Arts". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

^ ab

1987 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Sections 6–9, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

^ Order No. 74 (2009) Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine.. Department of Education.

^ DO 16, s. 2012

^ Dumlao, Artemio (21 May 2012). "K+12 to use 12 mother tongues". philstar.com.

^ Philippine Census, 2000. Table 11. Household Population by Ethnicity, Sex and Region: 2000

^ ab Lewis, M.P., Simons, G.F., & Fennig, C.D. (2014). Tagalog. Ethnologue: Languages of the

World. Retrieved from http://www.ethnologue.com/language/tgl

^ Soberano, Ros (2015). "The dialects of Marinduque Tagalog" (PDF). B-69. doi:10.15144/PL-B69.

^ Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Educational characteristics of the Filipinos bat man, National Statistics Office, March 18, 2005, archived from the original on January 27, 2008, retrieved 2008-01-21

^ Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Population expected to reach 100 million Filipinos in 14 years, National Statistics Office, October 16, 2002, retrieved 2008-01-21

^ "Language Use in the United States: 2007" (PDF). United States. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

^ "Tagalog Language". Archived from the original on 2017-02-12.

^ abcdefg Tagalog (2005). Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

^ ab "Accusations of Foreign-ness of the Revista Católica de Filipinas - Is 'K' a Foreign Agent? Orthography and Patriotism..." www.espanito.com.

^ abcde Thomas, Megan C. (8 October 2007). "K is for De-Kolonization: Anti-Colonial Nationalism and Orthographic Reform". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 49 (04): 938–967. doi:10.1017/S0010417507000813.

^ "Ebolusyon ng Alpabetong Filipino". Retrieved 2010-06-22.

^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (April 10, 2001). "The evolution of the native Tagalog alphabet". Philippines: Emanila Community (emanila.com). Views & Reviews. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

^ Signey, Richard, Philippine Journal of Linguistics, Manila, Philippines: Linguistic Society of the Philippines, The Evolution and Disappearance of the "Ğ" in Tagalog orthography since the 1593 Doctrina Christiana, ISSN 0048-3796, OCLC 1791000, retrieved August 3, 2010.

^ Linda Trinh Võ; Rick Bonus (2002), Contemporary Asian American communities: intersections and divergences, Temple University Press, pp. 96, 100, ISBN 978-1-56639-938-8

^ University of the Philippines College of Education (1971), "Philippine Journal of Education", Philippine Journal of Education, Philippine Journal of Education., 50: 556

^ Perfecto T. Martin (1986), Diksiyunaryong adarna: mga salita at larawan para sa bata, Children's Communication Center, ISBN 978-971-12-1118-9

^ Trinh & Bonus 2002, pp. 96, 100

^ Renato Perdon; Periplus Editions (2005), Renato Perdon, ed., Pocket Tagalog Dictionary: Tagalog-English/English-Tagalog, Tuttle Publishing, pp. vi–vii, ISBN 978-0-7946-0345-8

^ Michael G. Clyne (1997), Undoing and redoing corpus planning, Walter de Gruyter, p. 317, ISBN 978-3-11-015509-9

^ Worth, Roland H. Biblical Studies On The Internet: A Resource Guide, 2008 (p. 43)

^ "Genesis 1 Tagalog: Ang Dating Biblia (1905)". Adb.scripturetext.com. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

^ 2003 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses. Watch Tower Society. p. 155.

^ "Watchtower Online Library (Tagalog)". Watch Tower Society.

^ The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, The United Nations.

External links

| For a list of words relating to Tagalog language, see the Tagalog language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Tagalog edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Tagalog |

Tagalog language repository of Wikisource, the free library |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Filipino phrasebook. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tagalog language. |

- Tagalog Dictionary

- Tagalog verbs with conjugation

- Filipino Lessons Dictionary

- Tagalog Quotes

- Tagalog Translate

Kaipuleohone archive of Tagalog