Juan de Fuca Plate

| Juan de Fuca Plate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Minor |

| Approximate area | 250,000 km2 (96,000 sq mi)[1] |

| Movement1 | north-east |

| Speed1 | 26 mm/year (1.0 in/yr) |

| Features | Pacific Ocean |

1Relative to the African Plate | |

Cutaway of the Juan de Fuca Plate. USGS image

The Juan de Fuca Plate is a tectonic plate generated from the Juan de Fuca Ridge and is subducting under the northerly portion of the western side of the North American Plate at the Cascadia subduction zone. It is named after the explorer of the same name. One of the smallest of Earth's tectonic plates, the Juan de Fuca Plate is a remnant part of the once-vast Farallon Plate, which is now largely subducted underneath the North American Plate.

Contents

1 Origins

2 Extent

3 Volcanism

4 Earthquakes

5 Carbon sequestration potential

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Origins

The Juan de Fuca plate system has its origins with Panthalassa's oceanic basin and crust. This oceanic crust has primarily been subducted under the North American plate, and the Eurasian Plate. Panthalassa's oceanic plate remnants are understood to be the Juan de Fuca, Gorda, Cocos and the Nazca plates, all four of which were part of the Farallon Plate.

Extent

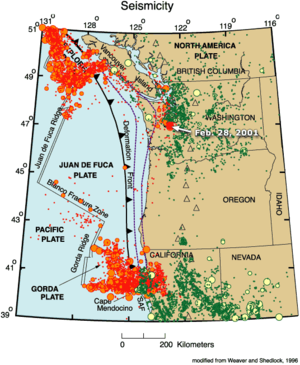

A map of the Juan de Fuca Plate

The Juan de Fuca plate is bounded on the south by the Blanco Fracture Zone (running northwest off the coast of Oregon), on the north by the Nootka Fault (running southwest off Nootka Island, near Vancouver Island, British Columbia) and along the west by the Pacific Plate (which covers most of the Pacific Ocean and is the largest of Earth's tectonic plates). The Juan de Fuca plate itself has since fractured into three pieces, and the name is applied to the entire plate in some references, but in others only to the central portion. The three fragments are differentiated as such: the piece to the south is known as the Gorda Plate and the piece to the north is known as the Explorer Plate. The separate pieces are demarcated by the large offsets of the undersea spreading zone.

Volcanism

This subducting plate system has formed the Cascade Range, the Cascade Volcanic Arc, and the Pacific Ranges, along the west coast of North America from southern British Columbia to northern California. These in turn are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a much larger-scale volcanic feature that extends around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean.

Earthquakes

The last megathrust earthquake at the Cascadia subduction zone was the 1700 Cascadia earthquake, estimated to have a moment magnitude of 8.7 to 9.2. Based on carbon dating of local tsunami deposits, it is inferred to have occurred around 1700.[2] Evidence of this earthquake is also seen in the ghost forest along the bank of the Copalis River in Washington. The rings of the dead trees indicate that they died around 1700, and it is believed that they were killed when the earthquake occurred and sunk the ground beneath them causing the trees to be flooded by saltwater.[3] Japanese records indicate that a tsunami occurred in Japan on 26 January 1700, which was likely caused by this earthquake.[4]

In 2008, small earthquakes were observed within the Juan de Fuca Plate. The unusual quakes were described as "more than 600 quakes over the past 10 days in a basin 150 miles [240 km] southwest of Newport". The quakes were unlike most quakes in that they did not follow the pattern of a large quake, followed by smaller aftershocks; rather, they were simply a continual deluge of small quakes. Furthermore, they did not occur on the tectonic plate boundary, but rather in the middle of the plate. The subterranean quakes were detected on hydrophones, and scientists described the sounds as similar to thunder, and unlike anything previously recorded.[5]

Carbon sequestration potential

The basaltic formations of the Juan de Fuca Plate could potentially be suitable for long-term CO2 sequestration as part of a carbon capture and storage (CCS) system. Injection of CO2 would lead to the formation of stable carbonates. It is estimated that 100 years of US carbon emissions (at current rate) could be stored securely, without risk of leakage back into the atmosphere.[6][7]

See also

- Astoria Fan

- Cascadia Channel

- Geology of the Pacific Northwest

- Plate tectonics

References

^ "Sizes of Tectonic or Lithospheric Plates". Geology.about.com. 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2016-01-06..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Wong, Florence L. "Seaside, Oregon, Tsunami Pilot Study GIS, USGS Data Series 236, home page". pubs.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-15.

^ Schulz, Kathryn (June 20, 2015). "The Earthquake That Will Devastate the Pacific Northwest". The New Yorker.

^ Satake, Kenji; Wang, Kelin; Atwater, Brian F. (2003-11-01). "Fault slip and seismic moment of the 1700 Cascadia earthquake inferred from Japanese tsunami descriptions". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 108 (B11): 2535. Bibcode:2003JGRB..108.2535S. doi:10.1029/2003JB002521. ISSN 2156-2202.

^ "Unusual Earthquake Swarm Off Oregon Coast Puzzles Scientists". Science News. ScienceDaily. 2008-04-14.

^ Goldberg, D. S. (2008-07-22). "Carbon dioxide sequestration in deep-sea basalt". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (29): 9920–9925. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9920G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804397105. PMC 2464617. PMID 18626013. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

^ Fairley, Jerry (January 2013). "Sub-seafloor Carbon Dioxide Storage Potential on the Juan de Fuca Plate, Western North America". Energy Procedia. 37: 5248–5257. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.441. Retrieved 2017-04-15.

External links

- National Geographic on Japanese records verifying an American earthquake

- Cascadia tectonic history with map