Copa Libertadores

| |

| Organising body | CONMEBOL |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1960 (1960) |

| Region | South America |

| Number of teams | 47 (from 10 associations) |

| Qualifier for | Recopa Sudamericana FIFA Club World Cup |

| Related competitions | Copa Sudamericana |

| Current champions | (4th title) |

| Most successful club(s) | (7 titles) |

| Television broadcasters | Fox Sports (Latin America) Fox Sports (Brazil) |

| Website | Official website |

The CONMEBOL Libertadores, named as Copa Libertadores de América (Portuguese: Copa Libertadores da América or Taça Libertadores da América), is an annual international club football competition organized by CONMEBOL since 1960. It is one of the most prestigious tournaments in the world and the most prestigious club competition in South American football. The tournament is named in honor of the Libertadores (Spanish and Portuguese for liberators), the main leaders of the South American wars of independence,[1] so a literal translation of its name into English would be "America's Liberators Cup".

The competition has had several different formats over its lifetime. At the beginning, only the champions of the South American leagues participated. In 1966, the runners-up of the South American leagues began to join. In 1998, Mexican teams were invited to compete, and have contested regularly since 2000, when the tournament was expanded from 20 to 32 teams. Today at least four clubs per country compete in the tournament, while Argentina and Brazil have six and seven clubs participating, respectively. Traditionally, a group stage has always been used but the number of teams per group has varied several times.[1][2]

In the present format, the tournament consists of six stages, with the first stage taking place in early February. The six surviving teams from the first stage join 26 teams in the second stage, in which there are eight groups consisting of four teams each. The eight group winners and eight runners-up enter the final four stages, better known as the knockout stages, which ends with the finals anywhere between November and December. The winner of the Copa Libertadores becomes eligible to play in the FIFA Club World Cup and the Recopa Sudamericana.[3]

Independiente of Argentina is the most successful club in the cup's history, having won the tournament seven times. Argentine clubs have accumulated the most victories with 25 wins, while Brazil has the largest number of different winning teams, with a total of 10 clubs having won the title. The cup has been won by 24 different clubs, 13 of which have won the title more than once, and won consecutively by six clubs.[4]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Beginnings: 1960–1969

1.2 Argentine decade: 1970–1979

1.3 Pacific emergence and last Uruguayan triumphs: 1980–1989

1.4 1990–1999

1.5 Decade of resurgences: 2000–2009

1.6 Brazilian dominance: 2010–2013

1.7 Argentine comeback: 2014–2015

2 Format

2.1 Qualification

2.2 Rules

2.3 Tournament

3 Prizes

3.1 Trophy

3.2 Prize money

4 Cultural impact

4.1 The "Sueño Libertador"

4.2 'La Copa se mira y no se toca'

5 Ambassador

6 Media coverage

7 Sponsorship

8 Match ball

9 Records and statistics

9.1 Performances by club

9.2 Performances by country

9.3 Top scorers

9.4 Most appearances

10 See also

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

History

The clashes for the Copa Aldao between the champions of Argentina and Uruguay kindled the idea of a continental competition in the 1930s.[1] In 1948, the South American Championship of Champions (Spanish: Campeonato Sudamericano de Campeones), the most direct precursor to the Copa Libertadores, was played and organized by Chilean club Colo-Colo after years of planning and organization.[1] Held in Santiago, it brought together the champions of each nation's top national leagues.[1] The tournament was won by Vasco da Gama of Brazil.[1][5][6]

In 1958, the basis and format of the competition was created by Peñarol's board leaders. On March 5, 1959, at the 24th South American Congress held in Buenos Aires, the competition was approved by the International Affairs Committee. In 1965, it was named in honor of the heroes of South American liberation, such as Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín, Pedro I, Bernardo O'Higgins, and José Gervasio Artigas, among others.[1]

Beginnings: 1960–1969

The first edition of the Copa Libertadores took place in 1960. Seven teams participated: Bahia of Brazil, Jorge Wilstermann of Bolivia, Millonarios of Colombia, Olimpia of Paraguay, Peñarol of Uruguay, San Lorenzo of Argentina and Universidad de Chile. All these teams were domestic champions of their respective leagues in 1959. The first Copa Libertadores match took place on April 19, 1960. It was won by Peñarol, who defeated Jorge Wilstermann 7–1. The first goal in Copa Libertadores history was scored by Carlos Borges of Peñarol. The Uruguayans won the first ever edition, defeating Olimpia in the finals, and successfully defended the title in 1961.[7]

Peñarol winning the 1966 Copa Libertadores

The Copa Libertadores did not receive international attention until its third edition, when the sublime football of a Santos team led by Pelé, considered by some the best club team of all time, earned worldwide admiration.[8]Os Santásticos, also known as O Balé Branco (the white ballet) won the title in 1962 defeating defending champions Peñarol in the finals.[9]A year later, O Rei and his compatriot Coutinho demonstrated their skills again in the form of tricks, dribbles, backheels, and goals including two in the second leg of the final at La Bombonera, to subdue Boca Juniors 2–1 and retain the trophy.[9][10]

Argentine football finally inscribed their name on the winner's list in 1964 when Independiente became the champions after disposing of reigning champions Santos and Uruguayan side Nacional in the finals.[11][12] Independiente successfully defended the title in 1965;[12] Peñarol would defeat River Plate in a playoff to win their third title,[7] and Racing would go on to claim the spoils in 1967.[13] One of the most important moments in the tournament's early history occurred in 1968 which saw Estudiantes participate for the first time.[14]

Estudiantes, a modest neighborhood club and a relatively minor team in Argentina, had an unusual style that prioritized athletic preparation and achieving results at all costs.[15][16][17][18] Led by coach Osvaldo Zubeldía and a team built around figures such as Carlos Bilardo, Oscar Malbernat and Juan Ramón Verón, went on to become the first ever tricampeón of the competition.[19][20][21][22] The pincharratas won their first title in 1968 by defeating Palmeiras. They successfully defended the title in 1969 and 1970 against Nacional and Peñarol, respectively.[23][24] Although Peñarol was the first club to win three titles, Estudiantes were the first to win three consecutive titles.

Argentine decade: 1970–1979

The Estudiantes de La Plata squad that won the title in 1968, 1969 and 1970

The 1970s were dominated by Argentine clubs, with the exception of three seasons. In a rematch of the 1969 finals, Nacional emerged as the champions of the 1971 tournament after overcoming an Estudiantes squad depleted of key players.[25] With two titles already under their belt, Independiente created a winning formula with the likes of Francisco Sa, José Omar Pastoriza, Ricardo Bochini and Daniel Bertoni: pillars of the titles of 1972, 1973, 1974, and 1975.[12] Independiente's home stadium, La Doble Visera, became one of the most dreaded venues for visiting teams to play at.[26] The first of these titles came in 1972 when Independiente came up against Universitario de Deportes of Peru in the finals. Universitario became the first team from the Pacific coast to reach the finals after eliminating Uruguayan giants Peñarol and defending champions Nacional at the semifinal stage. The first leg in Lima ended in a 0–0 tie, while the second leg in Avellaneda finished 2–1 in favor of the home team. Independiente successfully defended the title a year later against Colo-Colo after winning the playoff match 2–1. Los Diablos Rojos retained the trophy in 1974 after defeating São Paulo 1–0 in a hard-fought playoff. In 1975, Unión Española also failed to dethrone the champions in the finals after losing the playoff 2–0.

The reign of Los Diablos Rojos finally ended in 1976 when they were defeated by fellow Argentine club River Plate in the second phase in a dramatic playoff for a place in the finals. However, in the finals River Plate themselves would be beaten by Cruzeiro of Brazil, which was the first victory by a Brazilian club in 13 years.[27]

After having the trophy elude them in 1963 at the hands of Pelé's Santos, Boca Juniors finally managed to appear on the continental football map. Towards the end of the decade, the Xeneizes reached the finals in three consecutive years. The first was in 1977 in which Boca earned their first victory against defending champions Cruzeiro.[28] After both teams won their home legs 1–0, a playoff at a neutral venue was chosen to break the tie. The playoff match finished in a tense 0–0 tie and was decided by a penalty shootout. Boca Juniors won the trophy again in 1978 after thumping Deportivo Cali of Colombia 4–0 in the second leg of the finals.[29] In the following year, it looked as though Boca Juniors would also achieve a triple championship, only to have Olimpia end their dream after a highly volatile second leg match in Buenos Aires.[30] As in 1963, Boca Juniors had to watch as the visiting team lifted the Copa Libertadores in their home ground and Olimpia became the first (and, as of 2018[update], only) Paraguayan team to lift the Copa.

Pacific emergence and last Uruguayan triumphs: 1980–1989

Nacional won its second Libertadores in 1980

Nine years after their first triumph, Nacional won their second cup in 1980 after overcoming Internacional. Despite Brazil's strong status as a football power in South America, 1981 marked only the fourth title won by a Brazilian club. Flamengo, led by stars such as Zico, Júnior, Leandro, Adílio, Nunes, Cláudio Adão, Tita and Carpegiani, sparkled as the Mengão's Golden Generation reached the pinnacle of their careers by beating Cobreloa of Chile.[31][32]

Fernando Morena (left) and Walter Olivera holding the trophy won in 1982

After 16 years of near-perennial failure, Peñarol would go on to win the cup for the fourth time in 1982 after beating the 1981 finalists in consecutive series.[7] First, the Manyas disposed of defending champions Flamengo 1–0 in the last match of the second phase at Flamengo's home ground, the famed Estádio do Maracanã. In the final, they repeated the feat, beating Cobreloa in a decisive second leg match 1–0 in Santiago. Grêmio of Porto Alegre made history by defeating Peñarol to become the champion in 1983.[33] In 1984, Independiente won their seventh cup, a record that stands today, after defeating title holders Grêmio in a final which included a 1–0 win in the first away leg, highlighting Jorge Burruchaga and a veteran Ricardo Bochini.[12]

Argentinos Juniors won the 1985 Libertadores after defeating América de Cali by penalty shoot-out

Another team rose from the Pacific, as had Cobreloa. Colombian club América reached three consecutive finals in 1985, 1986 and 1987 but like Cobreloa they could not manage to win a single one. In 1985, Argentinos Juniors, a small club from the neighborhood of La Paternal in Buenos Aires, astonished South America by eliminating holders Independiente in La Doble Visera 2–1 during the last decisive match of the second round, to book a place in the final. Argentinos Juniors went on to win an unprecedented title by beating America de Cali in the play-off match via a penalty shootout.[34] After the frustrations of 1966 and 1976, River Plate reached a third final in 1986 and were crowned champions for the first time ever after winning both legs of the final series against America de Cali, 2–1 at the Estadio Pascual Guerrero and 1–0 at Estadio Monumental Antonio Vespucio Liberti.[35][36] Peñarol won the Cup again in 1987 after beating America de Cali 2–1 in the decisive playoff;[7] it proved to be their last hurrah in the international scene as Uruguayan football, in general, suffered a great decline at the end of the 1980s.[37] The Manyas fierce rivals, Nacional, also won one last cup in 1988 before falling from the continental limelight.

It was not until 1989 that a Pacific team finally broke the dominance of the established Atlantic powers. Atlético Nacional of Medellín won the final series, thus becoming the first team from Colombia to win the tournament. Atletico Nacional faced off against Olimpia losing the first leg in Asunción 2–0. Because Estadio Atanasio Girardot, their home stadium, did not have the minimum capacity CONMEBOL required to host a final, the second leg was played in Bogota's El Campín with the match ending 2–0 in favor of Atletico Nacional. Having tied the series, Atletico Nacional become that year's champions after winning a penalty shootout which required four rounds of sudden death.[38] Goalkeeper René Higuita cemented his legendary status with an outstanding performance as he stopped four of the nine Paraguayan kicks and scored one himself.[39] The 1989 edition also had another significant first: it was the first ever time that no club from Argentina, Uruguay, or Brazil managed to reach the final. That trend would continue until 1992.

1990–1999

Having led Olimpia to the 1979 title as manager, Luis Cubilla returned to the club in 1988. With the legendary goalkeeper Ever Hugo Almeida, Gabriel González, Adriano Samaniego, and star Raul Vicente Amarilla, a rejuvenated decano boasted a formidable side that promised a return to the glory days of the late 1970s. After coming up short in 1989 against Atlético Nacional, Olimpia reached the 1990 Copa Libertadores finals after defeating the defending champion in a climactic semifinal series decided on penalties. In the finals, Olimpia defeated Barcelona of Ecuador 3–1 in aggregate to win their second title.[30] Olimpia reached the 1991 Copa Libertadores finals, once again, defeating Atlético Nacional in the semifinals and facing Colo-Colo of Chile in the final. Led by Yugoslavian coach Mirko Jozić, the Chilean squad beat the defending champion 3–0. The defeat brought Olimpia's second golden era to a close.[40]

In 1992, São Paulo rose from being a mere great in Brazil to become an international powerhouse. Manager Telê Santana turned to the Paulistas' youth and instilled his style of quick, cheerful, and decisive football. Led by stars such as Zetti, Müller, Raí, Cafu, Palhinha, São Paulo beat Newell's Old Boys of Argentina to begin a dynasty.[41] In 1993 São Paulo successfully defended the title by thumping Universidad Católica of Chile in the finals.[41] The Brazilian side became the first club since Boca Juniors in 1978 to win 2 consecutive Copa Libertadores. Like Boca Juniors, however, they would reach another final in 1994 only to lose the title to Vélez Sársfield of Argentina in a penalty shoot-out.[42]

With a highly-compact tactical lineup and the goals of the formidable duo Jardel and Paulo Nunes, Grêmio won the coveted trophy again in 1995 after beating an Atlético Nacional led, once again, by the iconic figure of René Higuita.[43] Jardel finished the season as top scorer with 12 goals. The team coached by Luiz Felipe Scolari was led by defender (and captain) Adilson and the skilful midfielder Arilson. In the 1996 season, figures such as Hernán Crespo, Matías Almeyda and Enzo Francescoli helped River Plate secure its second title after defeating América de Cali in a rematch of the 1986 final.[44]

The Copa Libertadores stayed on Brazilian soil for the remainder of the 1990s as Cruzeiro, Vasco da Gama and Palmeiras took the spoils. The cup of 1997 pitted Cruzeiro against Peruvian club Sporting Cristal. The key breakthrough came in the second leg of the final when Cruzeiro broke the deadlock with just under 15 minutes left in a match attended by over 106,000 spectators in the Mineirão.[27] Vasco da Gama defeated Barcelona SC with ease to record their first title in 1998. The decade ended on a high note when Palmeiras and Deportivo Cali, both runners-up in the competition before, vied to become winners for the first time in 1999. The final was a dramatic back-and-forth match that went into penalties. Luiz Felipe Scolari managed to lead yet another club to victory as the Verdão won 4–3 in São Paulo.[45][46]

This decade proved to be a major turning point in the history of the competition as the Copa Libertadores went through a great deal of growth and change. Having long been dominated by teams from Argentina, Brazil began to overshadow their neighbors as their clubs reached eight finals and won six titles in the 1990s.[47]

From 1998 onwards, the Copa Libertadores was sponsored by Toyota and became known as the Copa Toyota Libertadores.[48] That same year, Mexican clubs, although affiliated to CONCACAF, started taking part in the competition thanks to quotas obtained from the Pre-Libertadores which pitted Mexican and Venezuelan clubs against each other for two slots in the group stage.[2] The tournament was expanded to 34 teams and economic incentives were introduced by an agreement between CONMEBOL and Toyota Motor Corporation.[48] All teams that advanced to the second stage of the tournament received $25,000 for their participation.[49]

Decade of resurgences: 2000–2009

During the 2000 Copa Libertadores, Boca Juniors returned to the top of the continent and raised the Copa Libertadores again after 22 years. Led by Carlos Bianchi, the Virrey, along with outstanding players like Mauricio Serna, Jorge Bermúdez, Óscar Córdoba, Juan Roman Riquelme, and Martín Palermo, among others, revitalized the club to establish it among the world's best.[50] The Xeneizes started this legacy by defeating defending champion Palmeiras in the final series.[51] Boca Juniors won the 2001 edition after, once again, defeating Palmeiras in the semifinals and Cruz Azul in the final series to successfully defend the trophy.[4][52] Cruz Azul became the first ever Mexican club to reach the final and win a final leg after great performances against River Plate and an inspired Rosario Central. Like their predecessors from the late 1970s however, Boca Juniors would fall short of winning three consecutive titles. As with Juan Carlos Lorenzo's men, the Xeneizes became frustrated as they were eliminated by Olimpia, this time during the quarterfinals. Led by World Cup winner-turned manager Nery Pumpido, Olimpia would overcome Grêmio (after some controversy) and surprise finalists São Caetano.[30] Despite this triumph, Olimpia did not create the winning mystique of its past golden generations and bowed out in the round of 16 the following season, after being routed by Grêmio 6–2, avenging their controversial loss from the year before.

São Paulo became tri-campeão after defeating Atlético Paranaense in 2005.

The 2003 tournament became an exceptional show as many teams such as América de Cali, River Plate, Grêmio, Cobreloa, and Racing, among others, brought their best sides in generations and unexpected teams such as Independiente Medellín and Paysandu became revelations in what was, arguably, the best Copa Libertadores in history.[53] The biggest news of the competition was previous champion Santos. Qualifying to the tournament as Brazilian champion, coached by Emerson Leão and containing marvelous figures such as Renato, Alex, Léo, Ricardo Oliveira, Diego, Robinho, and Elano, the Santásticos became a symbol of entertaining and cheerful football that resembled Pelé's generation of the 1960s. Boca Juniors once again found talent in their ranks to fill the gap left by the very successful group of 2000–2001 (with upcoming stars Rolando Schiavi, Roberto Abbondanzieri and Carlos Tevez). Boca Juniors and Santos would eventually meet in a rematch of the 1963 final; Boca avenged the 1963 loss by defeating Santos in both legs of the final.[54][55] Carlos Bianchi won the Cup for a fourth time and became the most successful manager in the competition's history and Boca Juniors hailed themselves pentacampeones. Boca reached their fourth final in five tournaments in 2004 but were beaten by surprise-outfit Once Caldas of Colombia, ending Boca's dream generation.[54] Once Caldas, employing a conservative and defensive style of football, became the second Colombian side to win the competition.

Olimpia squad that won the 2002 edition

Ruing their semifinal exit in 2004, São Paulo made an outstanding comeback in 2005 to contest the final with Atlético Paranaense. This became the first ever Copa Libertadores finals to feature two teams from the same football association;[56] The Tricolor won their third crown after thrashing Atlético Paranaense in the final leg.[41] The 2006 final was also an all-Brazilian affair, with defending champions São Paulo lining up against Internacional. Led by team captain Fernandão, the Colorados beat São Paulo 2–1 at Estádio do Morumbi and held the defending champions at a 2–2 draw at home in Porto Alegre as Internacional won their first ever title.[57][58] Internacional's arch-rivals, Grêmio, surprised many by reaching the 2007 final with a relatively young squad. However, it was not to be as Boca Juniors, reinforced by aging but still-capable players, came away with the trophy to win their sixth title.[59][60]

Peñarol vs Santos in the Estadio Centenario of Montevideo during the 2011 final

In 2008 the tournament severed its relationship with Toyota. Grupo Santander, one of the largest banks in the world, became the sponsor of the Copa Libertadores, and thus the official name changed to Copa Santander Libertadores.[48] In that season, LDU Quito became the first team from Ecuador to win the Copa Libertadores after defeating Fluminense 3–1 on penalties. Goalkeeper Jose Francisco Cevallos played a key role, saving three penalties in the final shootout in what is considered one of the best ever final series in the competition's history.[61][62] It was also the highest-scoring final in the history of the tournament. The biggest resurgence of the decade happened in the 50th edition of the Copa Libertadores and it was won by a former power that has reinvented itself. Estudiantes de La Plata, led by Juan Sebastián Verón, won their fourth title 39 long years after the successful generation of the 1960s (led by Juan Sebastián's father, Juan Ramón). The pincharatas managed to emulate their predecessors by defeating Cruzeiro 2–1 on the return leg in Belo Horizonte.[47][63]

Brazilian dominance: 2010–2013

In 2010, a spell of the competition only being won by Brazilian clubs for four years began with Internacional defeating Guadalajara.[64] In 2011, Santos won their third Copa, overcoming Peñarol by 2–1 in the final.[65] In 2012, Corinthians won the tournament undefeated, beating Boca Juniors 2–0 in the final. It was Corinthians' first title.[66] In 2013, Atlético Mineiro needed to beat Olimpia 2–0 in the second leg to take the match to penalties and did so; Victor, the goalkeeper, performed spectacularly and helped secure the title for the club. It was Atlético Mineiro's first title.[67]

Argentine comeback: 2014–2015

The Brazilian spell ended with San Lorenzo's first title, beating Nacional of Paraguay in the finals. But another trend was born, as once again a new champion was crowned, for the third consecutive year. San Lorenzo's victory was then followed by another Argentine club's victory, River Plate, winning its third title on 2015. But Atletico Nacional stopped this new trend, by beating Ecuador's Independiente del Valle on a 2-1 aggregate. The Colombian team won their second title after 27 years and one former failure attempt in 1995 against Grêmio, becoming the first pacific team to reach that achievement in the history of the tournament. The forementioned team later won the competition for the third time in its history after 22 years in 2017 after defeating CA Lanús in the final, with a 3-1 aggregate. In 2018, River Plate went on to beat their archrivals Boca Juniors 3-1 in a thrilling return leg which was played at the Santiago Bernabeu Stadium at Madrid, Spain, for the very first time in history due to the lack of security in Buenos Aires, which forced the match to be played in Europe instead.

Format

Qualification

Most teams qualify for the Copa Libertadores by winning half-year tournaments called the Apertura and Clausura tournaments or by finishing among the top teams in their championship.[3] The countries that use this format are Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela.[3] Peru and Ecuador have developed new formats for qualification to the Copa Libertadores involving several stages.[3] Argentina, Brazil and Chile are the only South American leagues to use a European league format instead of the Apertura and Clausura format.[3] However, one berth for the Copa Libertadores can be won by winning the domestic cups in these countries.[3]

Peru, Uruguay and Mexico formerly used a second tournament to decide qualification for the Libertadores (the "Liguilla Pre-Libertadores" between 1992 and 1997, the "Liguilla Pre-Libertadores de América" since 1974 to 2009, and the InterLiga from 2004 to 2010, respectively).[2][3] Argentina used an analogous method only once in 1992. Since 2011, the winner of the Copa Sudamericana has qualified automatically for the following Copa Libertadores.[3][68]

For the 2019 edition, the different stages of the competition will be contested by the following teams:[3]

| First stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| First stage | ||

| ||

| Third stage | ||

| ||

| Group stage | ||

| ||

| Final stages | ||

|

The winners of the previous season's Copa Libertadores are given an additional entry if they do not qualify for the tournament through their domestic performance; however, if the title holders qualify for the tournament through their domestic performance, an additional entry is granted to the next eligible team, "replacing" the title holder.

Rules

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Unlike most other competitions around the world, the Copa Libertadores historically did not use extra time, or away goals.[3] From 1960 to 1987, two-legged ties were decided on points (teams would be awarded 2 points for a win, 1 point for a draw and 0 points for a loss), without taking goal difference into consideration. If both teams were level on points after two legs, a third match would be played at a neutral venue. Goal difference would only come into play if the third match was drawn. If the third match did not produce an immediate winner, a penalty shootout was used to determine a winner.[3]

From 1988 onwards, two-legged ties were decided on points, followed by goal difference, with an immediate penalty shootout if the tie was level on aggregate after full-time in the second leg.[3] Starting with the 2005 season, CONMEBOL began to use the away goals rule.[3] In 2008, the finals became an exception to the away goals rule and employed extra time.[3] From 1995 onwards, the "Three points for a win" standard, a system adopted by FIFA in 1995 that places additional value on wins, was adopted in CONMEBOL, with teams now earning 3 points for a win, 1 point for a draw and 0 points for a loss.

Tournament

The current tournament features 38 clubs competing over a six- to eight-month period. There are three stages: the first stage, the second stage and the knockout stage.

The first stage involves 12 clubs in a series of two-legged knockout ties.[3] The six survivors join 26 clubs in the second stage, in which they are divided into eight groups of four.[3] The teams in each group play in a double round-robin format, with each team playing home and away games against every other team in their group.[3] The top two teams from each group are then drawn into the knockout stage, which consists of two-legged knockout ties.[3] From that point, the competition proceeds with two-legged knockout ties to quarterfinals, semifinals, and the finals.[3] Between 1960 and 1987 the previous winners did not enter the competition until the semifinal stage, making it much easier to retain the cup.[3]

Between 1960 and 2004, the winner of the tournament participated for the now-defunct Intercontinental Cup or (after 1980) Toyota Cup, a football competition endorsed by UEFA and CONMEBOL, contested against the winners of the European Cup (since renamed the UEFA Champions League)[3] Since 2004, the winner has played in the Club World Cup, an international competition contested by the champion clubs from all six continental confederations. It is organized by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the sport's global governing body. Because Europe and South America are considered the strongest centers of the sport, the champions of those continents enter the tournament at the semifinal stage.[3] The winning team also qualifies to play in the Recopa Sudamericana, a two-legged final series against the winners of the Copa Sudamericana.[3]

Prizes

Trophy

The tournament shares its name with the trophy, also called the Copa Libertadores or simply la Copa, which is awarded to the Copa Libertadores winner. It was designed by goldsmith Alberto de Gasperi, an Italian-born emigrant to Peru, in Camusso Jewelry in Lima at the behest of CONMEBOL.[69] The top of the laurel is made of sterling silver, with the exception of the football player at the top (which is made of bronze with a silver coating).[70]

The pedestal, which contains badges from every winner of the competition, is made of hardwood plywood. The badges show the season, the full name of the winning club, and the city and nation from which the champions hail. To the left of that information is the club logo. Any club which wins three consecutive tournaments has the right to keep the trophy. Today, the current trophy is the third in the history of the competition.

Two clubs have kept the actual trophy after three consecutive wins:[71]

Estudiantes after their third consecutive win in 1970. They won a fourth in 2009.

Independiente after their third consecutive win, and fifth overall, in 1974. They have since won it twice more, in 1975 and 1984.

Prize money

As of 2018[update], clubs in the Copa Libertadores receive US$400,000 for advancing into the second stage and US$600,000 per home match in the group phase. That amount is derived from television rights and stadium advertising. The payment per home match increases to US$750,000 in the round of 16.[49] The prize money then increases as each quarterfinalist receives US$950,000, US$1,350,000 is given to each semifinalist, US$3,000,000 is awarded the runner-up, and the winner earns US$6,000,000.[49]

- Eliminated at the first stage: US$300,000

- Advanced to the second stage: US$400,000

- Second stage: US$600,000

- Round of 16: US$750,000

- Quarter-finals: US$950,000

- Semi-finals: US$1,350,000

- Losing finalist: US$3,000,000

- Winning the Final: US$6,000,000

The champions of the 2014 Copa Libertadores were awarded US$5,350,000 in prize money. The top goalscorer of the tournament received the Alberto Spencer Trophy and $30,000. The best player in the tournament received the Premio Santander and $30,000.[72][73] The Fair Play Trophy, sponsored by Samsung, was awarded for the first time in 2011 to the team with the best discipline in each season, along with $50000.[74][75]

Cultural impact

The Copa Libertadores occupies an important space in South American culture. The folklore, fanfare, and organization of many competitions around the world owe its aspects to the Libertadores.

The "Sueño Libertador"

The Sueño Libertador is a promotional phrase used by sports journalism in the context of winning or attempting to win the Copa Libertadores.[76] Thus, when a team gets eliminated from the competition, it is said that the team has awakened from the liberator dream. The project normally starts after the club win one's national league (which grants them the right to compete in the following year's Copa Libertadores).

It is common for clubs to spend large sums of money to win the Copa Libertadores. In 1998 for example, Vasco da Gama spent $10 million to win the competition, and in 1998, Palmeiras, managed by Luiz Felipe Scolari, brought Júnior Baiano among other players, winning the 1999 Copa Libertadores. The tournament is highly regarded among its participants. In 2010, players from Guadalajara stated that they would rather play in the Copa Libertadores final than appear in a friendly against Spain, then reigning world champions,[77] and dispute their own national league.[78] Similarly, after their triumph in the 2010 Copa do Brasil, several Santos players made it known that they wished to stay at the club and participate in the 2011 Copa Libertadores, despite having multimillion-dollar contracts lined up for them at clubs participating in the UEFA Champions League, such as Chelsea of England and Lyon of France.[79]

Former Boca Juniors goalkeeper Óscar Córdoba has stated that the Copa Libertadores was the most prestigious trophy he won in his career (above the Argentine league, Intercontinental Cup, etc.)[80]Deco, winner of two UEFA Champions League medals with Porto and Barcelona 2004 and 2006 respectively, stated he would exchange those two victories for a Copa Libertadores triumph.[81]

'La Copa se mira y no se toca'

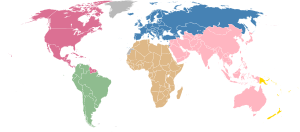

Since its inception in 1960, the Copa Libertadores had predominantly been won by clubs from nations with an Atlantic coast: Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. Olimpia of Paraguay became the first team outside of those nations to win the Copa Libertadores when they triumphed in 1979.

The first club from a country with a Pacific coast to reach a final was Universitario of Lima, Peru, who lost in 1972 against Independiente of Argentina.[12] The following year, Independiente defeated Colo-Colo of Chile, another Pacific team, creating the myth that the trophy would never go to the west, giving birth to the saying, "La Copa se mira y no se toca" (Spanish: The Cup is to be seen, not to be touched).[12]Unión Española became the third Pacific team to reach the final in 1975, although they also lost to Independiente.[12]Atletico Nacional of Medellín, Colombia, won the Copa Libertadores in 1989, becoming the first nation with a Pacific coastline to win the tournament.[38] In 1990 and 1998 Barcelona Sporting Club, of Ecuador also made it to final but lost both finals to Olimpia and Vasco da Gama respectively.

Other clubs from nations with Pacific coastlines to have won the competition are Colo-Colo of Chile in 1991, Once Caldas of Colombia in 2004, and LDU Quito of Ecuador in 2008. Atletico Nacional of Colombia in 2016, it was their second title. Particular mockery was used from Argentinian teams to Chilean teams for never having obtained the Copa Libertadores, so after Colo-Colo's triumph in 1991 a new phrase saying "la copa se mira y se toca" (Spanish: The Cup is seen and touched) was implemented in Chile.

Ambassador

Pelé

Pelé, regarded by many football historians, former players and fans to be the best footballer in the game's history,[82] is the ambassador of the Copa Libertadores, having won the competition with Santos twice.[83] In 1999, he was voted as the Football Player of the Century by the IFFHS International Federation of Football History and Statistics. In the same year, French weekly magazine France-Football consulted their former "Ballon D'Or" winners to elect the Football Player of the Century. Pelé came in first place.[84] In 1999 the International Olympic Committee named Pelé the "Athlete of the Century".[85]

Media coverage

The tournament attracts television audiences beyond South America, Mexico, and Spain. Matches are broadcast in over 135 countries, with commentary in more than 30 languages, and thus the Copa is often considered as one of the most watched sports events on TV;[86]Fox Sports, for example, reaches more than 25 million households in the Americas.[87]Movistar+ broadcasts live Copa Libertadores matches in Spain and Fox Deportes in the United States.[88]

Sponsorship

| Sponsors | ||

|---|---|---|

|

From 1997 to 2017, the competition had a single main sponsor for naming rights. The first major sponsor was Toyota, who signed a ten-year contract with CONMEBOL from 1997.[89] The second major sponsor was Banco Santander, who signed a five-year contract with CONMEBOL from 2008.[48] The third major sponsor was Bridgestone, who signed a sponsorship deal for naming rights for a period of five years from 2013 edition to 2017.[90]

Match ball

The Total 90 Omni CSF by Nike, the official match ball of the Copa Libertadores

Nike supplies the official match ball since 2003, as they do for all other CONMEBOL competitions.[91][92] The current match ball for the Copa Libertadores is the Ordem 5 Libertadores.[91] It is one of the many balls produced by the American sports equipment maker for CONMEBOL, replacing the Ordem 4 ball used during 2017. The ball, approved by FIFA and weighing approximately 422 g, has a spherical shape that allows the ball to fly faster, farther, and more accurately.[91] According to Nike, the ball's geometric precision distributes pressure evenly across panels and around the ball. The compressed polyethylene layer stores energy from impact and releases it at launch, and the six-wing carbon-latex air chamber improves acceleration.[91]

Another feature of the ball is its rubber layer; it was designed to allow a better response while retaining the impact energy and releases it in the coup.[91] Its support material of cross-linked nitrogen-expanded foam improves its retention and durability of its shape.[91]Polyester support fabric enhances structure and stability. The asymmetrical high-contrast graphic around the ball creates an optimal flicker as the ball rotates for a more powerful visual signal, allowing the player to more easily identify and track the ball.[91]

Records and statistics

Performances by club

Alberto Spencer scored 54 goals, a record that still stands today.

Daniel Onega scored a record 17 goals in a season during the 1966 tournament.

Performances in the Copa Libertadores finals by club | ||||

| Club | Titles | Runners-up | Seasons won | Seasons runner-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 0 | 1964, 1965, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1984 | — | |

| 6 | 5 | 1977, 1978, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2007 | 1963, 1979, 2004, 2012, 2018 | |

| 5 | 5 | 1960, 1961, 1966, 1982, 1987 | 1962, 1965, 1970, 1983, 2011 | |

| 4 | 2 | 1986, 1996, 2015, 2018 | 1966, 1976 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1968, 1969, 1970, 2009 | 1971 | |

| 3 | 4 | 1979, 1990, 2002 | 1960, 1989, 1991, 2013 | |

| 3 | 3 | 1971, 1980, 1988 | 1964, 1967, 1969 | |

| 3 | 3 | 1992, 1993, 2005 | 1974, 1994, 2006 | |

| 3 | 2 | 1983, 1995, 2017 | 1984, 2007 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1962, 1963, 2011 | 2003 | |

| 2 | 2 | 1976, 1997 | 1977, 2009 | |

| 2 | 1 | 2006, 2010 | 1980 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1989, 2016 | 1995 | |

| 1 | 3 | 1999 | 1961, 1968, 2000 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1991 | 1973 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1967 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 1981 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 1985 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 1994 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 1998 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2004 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2008 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2012 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2013 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2014 | — | |

Performances by country

| Country | Titles | Runners-up |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | 11 | |

| 18 | 15 | |

| 8 | 8 | |

| 3 | 7 | |

| 3 | 5 | |

| 1 | 5 | |

| 1 | 3 | |

| 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 |

Top scorers

| Rank | Country | Player | Goals | Games | Goal Ratio | Debut | Clubs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alberto Spencer | 54 | 87 | 0.62 | 1960 | ||

| 2 | Fernando Morena | 37 | 77 | 0.48 | 1973 | ||

| 3 | Pedro Rocha | 36 | 88 | 0.41 | 1962 | ||

| 4 | Daniel Onega | 31 | 47 | 0.66 | 1966 | ||

| 5 | Julio Morales | 30 | 76 | 0.39 | 1966 | ||

| 6 | Antony de Ávila | 29 | 94 | 0.31 | 1983 | ||

Juan Carlos Sarnari | 29 | 62 | 0.47 | 1966 | |||

Luizão | 29 | 43 | 0.67 | 1998 | |||

| 9 | Juan Carlos Sánchez | 26 | 53 | 0.49 | 1973 | ||

Luis Artime | 26 | 40 | 0.65 | 1966 |

Most appearances

| Rank | Country | Player | Appearances | Goals | From | To | Clubs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ever Hugo Almeida | 113 | 0 | 1973 | 1990 | Olimpia | |

| 2 | Antony de Ávila | 94 | 29 | 1983 | 1998 | América de Cali, Barcelona | |

| 3 | Vladimir Soria | 93 | 4 | 1986 | 2000 | Bolívar | |

| 4 | Willington Ortiz | 92 | 19 | 1973 | 1988 | Millonarios, América de Cali, Deportivo Cali | |

| 5 | Rogério Ceni | 90 | 14 | 2004 | 2015 | São Paulo | |

| 6 | Pedro Rocha | 88 | 36 | 1962 | 1979 | Peñarol, São Paulo, Palmeiras | |

| 7 | Alberto Spencer | 87 | 54 | 1960 | 1972 | Peñarol, Barcelona | |

Carlos Borja | 87 | 11 | 1979 | 1997 | Bolívar | ||

| 9 | Juan Battaglia | 85 | 22 | 1978 | 1990 | Cerro Porteño, América de Cali | |

| 10 | Álex Escobar | 83 | 14 | 1985 | 2000 | América de Cali, LDU Quito |

See also

- Copa Libertadores Femenina

- Football continental championships

References

^ abcdefg Carluccio, José (September 2, 2007). "¿Qué es la Copa Libertadores de América?" [What is the Copa Libertadores de América?] (in Spanish). Historia y Fútbol. Retrieved May 18, 2010..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abc "River y Colón no tienen fecha fija" [River and Colón do not have a date set] (in Spanish). La Nación. December 13, 1997. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvw "Reglamento CONMEBOL Libertadores 2019" [2019 CONMEBOL Libertadores Regulations] (PDF) (in Spanish). CONMEBOL. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

^ ab "Copa Libertadores 2001" (in Spanish). Historia de Boca. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ La Nación; Historia del Fútbol Chileno, 1985

^ Bekerman, Esteban (2008). Perfil.com, ed. "Hace 60 años, River perdía la gran chance de ser el primer club campeón de América" [60 years ago, River lost the chance to be the first club champion of America] (in Spanish). Retrieved May 10, 2008.

^ abcd "Peñarol: Spencer secures Peñarol's place in the pantheon". FIFA. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ Cunha, Odir (2003). Time dos Sonhos [Dream Teams] (in Portuguese). ISBN 85-7594-020-1.

^ ab "Principais Troféus" [Major Trophies] (in Portuguese). Santos FC. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ Duarte, Bellos, Pelé s. 103

^ Juvenal (August 19, 1964). "Independiente gana su primera Libertadores" [Independiente wins their first Libertadores] (in Spanish). El Gráfico. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ abcdefg "Copa Libertadores" (in Spanish). Club Atlético Independiente. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Palmares" [Titles] (in Spanish). Racing Club de Avellaneda. Archived from the original on April 6, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "1968—Campeón de América" [1968 – Champion of America] (in Spanish). Estudiantes de La Plata. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ Borocotó, Ricardo Lorenzo (1955). Historia del fútbol argentino [History of Argentine football] (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Eiffel.

^ Vicente, Néstor (2001). Ayer, Hoy y Siempre, El Sexto Grande [Yesterday, Today and Always, the Sixth Big One] (in Spanish). Buenos Aires.

^ Ramírez, Pablo (1979). Fútbol – Historia del Profesionalismo [Football – History of the Professional Era] (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Editorial Perfil.

^ Frydenberg, Julio David (1941). Historia de los Cinco Grandes [History of the Big Five] (in Spanish). Educación Física y Deportes.

^ "Don Osvaldo Zubeldía" (in Spanish). Estudiantes de La Plata. Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

^ "El Estudiantes de Zubeldía (1ra. parte)" [Zubeldía's Estudiantes (1st part)] (in Spanish). Os Clássicos. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "El Estudiantes de Zubeldía (2da. parte)" [Zubeldía's Estudiantes (2nd part)] (in Spanish). Os Clássicos. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "El Estudiantes de Zubeldía (3ra. parte)" [Zubeldía's Estudiantes (3rd part)] (in Spanish). Os Clássicos. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "1969—Campeón de América" [1969—Champion of America] (in Spanish). Estudiantes de La Plata. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "1970—Campeón de América" [1970—Campeón de América] (in Spanish). Estudiantes de La Plata. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ Pierrend, José Luis. "Copa Libertadores de América 1971". RSSSF. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ Geraldes, Pablo Aro (1979). Independiente, El campeón [Independiente, the champion] (in Spanish). Atlántida.

^ ab "Relação dos Títulos oficiais do Cruzeiro" [List of official Cruzeiro titles] (in Portuguese). Cruzeiro Esporte Clube. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores de América: 1977" (in Spanish). Boca Juniors. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores de América: 1978" (in Spanish). Boca Juniors. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ abc "Olimpia: Olimpia emerged triumphant in unlikely decider". FIFA. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ Vaz, Arturo (1979). Acima de Tudo Rubro-Negro [Above All Rubro-Negro] (in Portuguese). A História do C. R. Flamengo.

^ Neves, Mauricio. "A Libertadores de 1981" (in Portuguese). Clube de Regatas do Flamengo. Archived from the original on May 8, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "1983 – Libertadores" (in Portuguese). Grêmio. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Campeón Copa Libertadores de América / 1985" [Copa Libertadores de America Champion / 1985] (in Spanish). Argentinos Juniors. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ Barrio, José Luis (November 4, 1986). "River gana la Copa Libertadores" [River wins the Copa Libertadores] (in Spanish). El Gráfico. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores del 86" [1986 Copa Libertadores] (in Spanish). River Plate. Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Football, football, football". UruguayNow. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ ab "Palmarés" [Titles] (in Spanish). Atlético Nacional. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ Atlético Nacional, Rey de Copas [Atlético Nacional, King of Cups] (in Spanish). Periodico El Colombiano, Medellín, Colombia. 2004. p. 104. ISBN 958-693-696-1.

^ "El Club" (in Spanish). Colo-Colo. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ abc "El Club" (in Portuguese). São Paulo Futebol Clube. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Títulos" [Titles] (in Spanish). Vélez Sársfield. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "1995 – Libertadores" (in Portuguese). Grêmio. Archived from the original on January 8, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores del 96" [1996 Copa Libertadores] (in Spanish). Club Atlético River Plate. Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Há 10 anos, times brasileiros não são campeões diante de estrangeiros" [For 10 years, Brazilian clubs have not been champion in front of strangers] (in Portuguese). UOL Esporte. July 16, 2009. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ "Galeria de Títulos" [Gallery of Titles] (in Portuguese). Sociedade Esportiva Palmeiras. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ ab "Con la identidad de los años dorados" [With the identity of the golden years] (in Spanish). La Nación. July 16, 2009. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ abcd "Corporation Sponsorship". Santander Group. 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

^ abc Rodrigues, Rodolfo (January 22, 2018). "Com premiação recorde, Copa Libertadores 2018 começa hoje (in Portuguese)". R7. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ The Global Art of Soccer. Richard Witzig. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores de América: 2000" (in Spanish). Boca Juniors. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores de América: 2001" (in Spanish). Boca Juniors. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ Vickery, Tim (June 22, 2009). "Copa Libertadores runs dry". BBC. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ ab "Copa Libertadores 2003" (in Spanish). Historia de Boca. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores de América: 2003" (in Spanish). Boca Juniors. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ Freitas, Bruno (July 13, 2005). "Final brasileira histórica vê animosidade e provocações de diretorias" [Brazilian final sees the historical animosity and provocations of directors] (in Portuguese). UOL. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ "Eller é o único bicampeão da Libertadores no Inter" [Eller is the only bi-champion at Inter] (in Portuguese). Terra. August 17, 2006. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ "A histórica conquista da América" [The historic conquest of America] (in Portuguese). Internacional. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "De punta en Porto Alegre" [On point in Porto Alegre] (in Spanish). Clarín. June 27, 2007. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ "Copa Libertadores de América: 2007" (in Spanish). Boca Juniors. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Liga de Quito se proclama campeón de la Copa Libertadores" [Liga de Quito proclaimed champion of the Copa Libertadores] (in Spanish). El País. July 3, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

^ "Liga, El más grande en la historia del Ecuador" [Liga, the biggest in the history of Ecuador] (in Spanish). LDU Quito. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Rey de América" [King of America] (in Spanish). Estudiantes de La Plata. Archived from the original on March 25, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

^ "Inter é bicampeão da América!". Internacional (in Portuguese). August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

^ "Santos é campeão da Libertadores 2011". www.estadao.com.br (in Portuguese). June 23, 2011. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

^ "Emerson dá a América ao Corinthians: o time ganha a Libertadores pela 1.ª vez". www.estadao.com.br (in Portuguese). July 4, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

^ "Atlético vence nos pênaltis e é campeão da Libertadores". www.estadao.com.br (in Portuguese). July 25, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

^ "Magnífico sorteo de la Copa Nissan Sudamericana 2010 en Asunción" [Magnificent draw for the 2010 Copa Nissan Sudamericana in Asunción] (in Spanish). CONMEBOL. April 28, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^

Taringa.com (ed.). "Las chapitas de la Copa Libertadores" [The plaques of the Copa Libertadores] (in Spanish). Retrieved May 1, 2010.

^ "El trofeo de la Copa Libertadores se hizo en el Perú" [The Copa Libertadore trophy was made in Peru] (in Spanish). HD Mundo. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

^ "History of the Copa Libertdores". Historiayfutbol.obolog.com. 2009-06-10. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

^ "Salvador Cabañas, ganador por segunda vez del Premio Visa" [Salvador Cabañas, winner of the Visa Prize for the second time] (in Spanish). Multipress Dailynet. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ "Mauro Boselli recibió premio Goleador Visa Copa Santander Libertadores 2009" [Mauro Boselli received the 2009 Visa Copa Santander Libertadores Golden Boot prize] (in Spanish). CID News Media. August 6, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ "Conmebol anuncia nuevo Premio para Copa Libertadores". Starcomunicaciones.info. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

^ 12 de mayo de 2011 - 19:38. "Libertadores: Samsung y el premio Fair Play de la Copa". Minutouno.com.ar. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

^ Carter, Arturo Brizio (January 16, 2004). "Sueño Libertador" [Liberator Dream] (in Spanish). El Siglo de Durango. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

^ "España viene con 18 Campeones del Mundo" [Spain arrives with 18 world champions] (in Spanish). Medio Tiempo. August 5, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

^ Téllez, Juan (August 5, 2010). "Para Luis Michel la prioridad es la Copa Libertadores" [For Luis Michel the priority is the Copa Libertadores] (in Spanish). Medio Tiempo. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

^ "Quiero quedarme en Santos: Robinho" [Robinho: I want to stay en Santos] (in Spanish). Medio Tiempo. August 5, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

^ "Una copa, brindis y a dormir porque había que pensar en San Lorenzo" [A cup, a toast, and then to sleep because I have to think about San Lorenzo]. Cancha Llena. November 27, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

^ "Deco: "Cambio las dos Champions por ganar la Libertadores"" [Deco: "I would exchange two Champions [league trophies] for one [Copa] Libertadores.] (in Spanish). CONMEBOL. July 15, 2012. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

^ "The Best of The Best". Rsssf.com. June 19, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

^ "El Banco Santander renueva a Pelé como embajador de la Copa Libertadores" (in Spanish). Europapress.es. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

^ France Football's Football Player of the Century Retrieved May 1, 2011

^ "Pelé still in global demand". CNN Sports Illustrated. May 29, 2002. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

^ "Copa Libertadores TV revenues rise". Sports business. March 9, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

^ Amoroso, Sebastian. "Copa Libertadores: "We estimate to have about 70 matches filmed in HD"". TodoTV News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

^ "Boca vs River: la 'final del siglo' será en sábado: 10 y 24 de noviembre" (in Spanish). Marca. 1 November 2018.

^ "Bridgestone succeds Santander as Copa Libertadores title sponsor". Soccerrex. 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

^ "Bridgestone and Conmebol announce five-year sponsorship of Copa Libertadores". Bridgestone Americas. 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

^ abcdefg "Nike presentó la nueva pelota para el Torneo" [Nike presented the new ball for the tournament] (in Spanish). Info Bae. January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

^ "The Nike "Ordem" is the official ball of the 2014 Copa Bridgestone". Conmebol. 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Further reading

Goldblatt, David Goldblatt (2008). The Ball Is Round: A Global History of Soccer. Penguin Group. ISBN 1-59448-296-9.

Jozsa, Frank (2009). Global Sports: Cultures, Markets and Organizations. World Scientific. ISBN 981-283-569-5.

Barraza, Jorge (1990). Copa Libertadores de América, 30 años (in Spanish). Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol.

Napoleão, Antonio Carlos (1999). O Brasil na Taça Libertadores da América (in Portuguese). Mauad Editora Ltda. ISBN 85-7478-001-4.

External links

| Look up Sueño Libertador in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Copa Conmebol Libertadores. |

Listen to this article (info/dl)

- Official Website

Fútbol Santander Official Sponsor of the Copa Libertadores.- Copa Libertadores at Fox Sports en Español

- Copa Libertadores at ESPN

- Copa Libertadores at Goal

- Copa Libertadores at Univision

- Copa Libertadores at Fox Soccer

- Copa Libertadores results at RSSSF.com

- Copa Libertadores at worldfootball.net

- Copa Libertadores at southamericanfutbol.com