Christianity in Syria

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Approximately 10% of the population | |

| Religions | |

Christianity (denominations like Eastern Orthodoxy; Eastern Catholicism; Oriental Orthodoxy like Syriac Orthodox Church and Armenian Apostolic Church; Assyrian Church of the East; Roman Catholicism; Protestantism) | |

| Scriptures | |

The Bible (all denominations) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

Mosaic of Christ Pantocrator, Hagia Sophia |

Overview |

|

Background

|

Organization

|

Autocephalous jurisdictions

|

Ecumenical councils

|

History

|

Theology

|

Liturgy and worship

|

Liturgical calendar

|

Major figures

|

Other topics

|

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

History and theology

|

Liturgy and practices

|

Major figures

|

Other topics

|

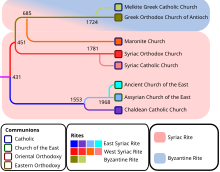

Christians in Syria make up about 10% of the population.[1][2] The country's largest Christian denomination is the Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch (known as the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East),[3][4] closely followed by the Melkite Catholic Church, one of the Eastern Catholic Churches, which has a common root with the Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch,[5] and then by an Oriental Orthodoxy churches like Syriac Orthodox Church and Armenian Apostolic Church. There are also a minority of Protestants and members of the Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church. The city of Aleppo is believed to have the largest number of Christians in Syria.

In the late Ottoman rule, a large percentage of Syrian Christians emigrated from Syria, especially after the bloody chain of events that targeted Christians in particular in 1840, the 1860 massacre, and the Assyrian genocide. According to historian Philip Hitti, approximately 900,000 Syrians arrived in the United States between 1899 and 1919 (more than 90% of them were Christians).[6]. The Syrians referred include historical Syria or the Levant encompassing Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine.

Contents

1 Origins

1.1 Eastern Orthodoxy

1.2 Oriental Orthodoxy

1.2.1 Syriac Orthodox Church

1.2.2 Armenian Apostolic Church

1.3 Protestant Churches

1.4 Catholic Church

1.4.1 Popes of the Catholic Church

2 Status of Christians in Syria

2.1 Integration

2.2 Separation

3 Christian cities/areas

4 Syrian Christians during the Syrian Civil War

5 Notable Christians

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Origins

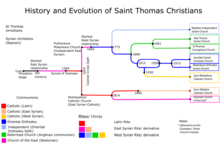

The Christian population of Syria comprise 11.2% of the population,[1] which is down from when they were 25% of Syrian the total population of 2.5 million in 1920. In Syria today there around 2.5 million among their population in Syria in 2010 before the civil war started. Most Syrians are members of either the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch (700,000), or the Syriac Orthodox Church. The vast majority of Catholics belong to the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, which was created as a result of a schism within the Greek Orthodox Church over a disputed election to the Patriarchal See of Antioch in 1724. Other Christian Churches in union with Rome include the Maronites, Syriac Catholics, Armenians, Chaldeans and a small number of Latin Rite Catholics. The rest belong to the Eastern communions, which have existed in Syria since the earliest days of Christianity. The main Eastern groups are:

- the autonomous Orthodox churches;

- the Eastern Catholic Churches, which are in communion with Rome;

- and the independent Assyrian Church of the East (i.e., the "Nestorian" Church). Followers of the Assyrian Church of the East are almost all Eastern Aramaic speaking ethnic Assyrians/Syriacs whose origins lie in Mesopotamia, as are some Oriental Orthodox and Catholic Christians. Even though each group forms a separate community, Christians nevertheless cooperate increasingly. Roman Catholicism and Protestantism were introduced by missionaries but only a small number of Syrians are members of Western denominations.

The schisms that brought about the many sects resulted from political and doctrinal disagreements. The doctrine most commonly at issue was the nature of Christ. In 431, the Nestorians were separated from the main body of the Church because of their belief in the dual character of Christ, i.e., that he had two distinct but inseparable "qnoma" (ܩܢܘܡܐ, close in meaning to, but not exactly the same as, hypostasis), the human Jesus and the divine Logos. Therefore, according to Nestorian belief, Mary was not the mother of God but only of the man Jesus. The Council of Chalcedon, representing the mainstream of Christianity, in 451 confirmed the dual nature of Christ in one person; Mary was therefore the mother of a single person, mystically and simultaneously both human and divine. The Miaphysites taught that the Logos took on an instance of humanity as His own in one nature. They were the precursors of the present-day Syrian and Armenian Orthodox churches.

By the thirteenth century, breaks had developed between Eastern or Greek Christianity and Western or Latin Christianity. In the following centuries, however, especially during the Crusades, some of the Eastern churches professed the authority of the pope in Rome and entered into or re-affirmed communion with the Catholic Church. Today called the Eastern Catholic churches, they retain a distinctive language, canon law and liturgy.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Antiochian Orthodox church of the Entrance of the Theotokos in Hama, Syria

The largest Christian denomination in Syria is the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch (officially named the Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East), also known as the Melkite church after the 5th and 6th century Christian schisms, in which its clergy remained loyal to the Eastern Roman Emperor ("melek") of Constantinople.

Adherents of that denomination generally call themselves "al-Rûm" which means "Eastern Roman" or "Asian Greek" in Turkish and Arabic. In that particular context, the term "Rûm" is used in preference to "Yāvāni" or "Ionani" which means "European-Greek" or Ionian in Biblical Hebrew and Classical Arabic. The appellation "Greek" refers to the Koine Greek liturgy used in their traditional prayers and priestly rites.

Members of the community sometimes also call themselves "Melkites", which literally means "supporters of the emperor" in Semitic languages - a reference to their past allegiance to Roman and Byzantine imperial rule. But, in the modern era, this designation tends to be more commonly used by followers of the local Melkite Catholic Church.

Syrians from the Greek Orthodox Community are also present in the Hatay Province of Southern Turkey (bordering Northern Syria), and have been well represented within the Syrian diasporas of Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, the United States, Canada and Australia.

Oriental Orthodoxy

Archbishop of Aleppo "Mor Gregorios Yohanna Ibrahim" (left) of the Syriac Orthodox Church, with Austrian politician Reinhold Lopatka in 2012

Traditional Christianity in Syria is also represented by Oriental Orthodox communities, that primarily belong to the ancient Syriac Orthodox Church, and also to the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Syriac Orthodox Church

The Syriac Orthodox Church is the largest Oriental Orthodox Christian group in Syria. The Syriac Orthodox or Jacobite Church, whose liturgy is in Syriac, was severed from the favored church of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Orthodoxy), over the Chalcedonian controversy.

Armenian Apostolic Church

The Armenian Apostolic Church is the second largest Oriental Orthodox Christian group in Syria. It uses an Armenian liturgy and its doctrine is Miaphysite (not monophysite, which is a mistaken term used or was used by the Chalcedonian Catholics and Chalcedonian Orthodox).

Protestant Churches

In Syria, there is also a minority of Protestants. Protestantism was introduced by European missionaries and a small number of Syrians are members of Protestant denominations. The Gustav-Adolf-Werk (GAW) as the Evangelical Church in Germany Diaspora agency actively supports persecuted Protestant Christians in Syria with aid projects.[7] A 2015 study estimates some 2,000 Muslim converted to Christianity in Syria, most of them belonging to some form of Protestantism.[8]

Catholic Church

The Monastery of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary in Aleppo.

Of the Eastern Catholic Churches the oldest is the Maronite, with ties to Rome dating at least from the twelfth century. Their status before then is unclear, some claiming it originally held to the Monothelite heresy up until 1215, while the Maronite Church claims it has always been in union with Rome. The liturgy is in Aramaic (Syriac).

Syrian Christians in a church in Damascus 2017

The Patriarchate of Antioch never recognized the mutual excommunications of Rome and Constantinople of 1054, so it was canonically still in union with both. After a disputed patriarchal election in 1724, it divided into two groups, one in union with Rome and the other with Constantinople. Today the term "Melkite" is in use mostly among the Greek Catholics of Syria and Lebanon. Like its sister-church the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch ('Eastern Orthodox'), the Melkite Greek Catholic Church uses both Greek and Arabic in its traditional liturgy. Most of the 375,000 Catholics in Syria belong to the Melkite Rite, the rest are Latin Rite, Maronites (52,000), Armenian or Syriac Rites.

Popes of the Catholic Church

Seven popes from Syria ascended the papal throne,[9][10] many of them lived in Italy, Pope Gregory III,[11][12] was previously the last pope to have been born outside Europe until the election of Francis in 2013.

| Numerical order | Pontificate | Portrait | Name English · Regnal | Personal name | Place of birth | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 – 64/67 |  | St Peter PETRUS | Simon Peter | Bethsaida, Galilea, Roman Empire | Saint Peter was from village of Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire |

| 11 | 155 to 166 |  | St Anicetus ANICETUS | Anicitus | Emesa, Syria | Traditionally martyred; feast day 17 April |

| 82 | 12 July 685 – 2 August 686 (1 year+) |  | John V Papa IOANNES Quintus | | Antioch, Syria | |

| 84 | 15 December 687 – 8 September 701 (3 year+) |  | St Sergius I Papa Sergius | | Sicily, Italy | Sergius I was born in Sicily, but he was from Syrian parentage[13] |

| 87 | 15 January 708 to 4 February 708 (21 days) |  | Sisinnius Papa SISINNIUS | | Syria | |

| 88 | 25 March 708 – 9 April 715 (7 years+) |  | Constantine Papa COSTANTINUS sive CONSTANTINUS | | Syria | Last pope to visit Greece while in office, until John Paul II in 2001 |

| 90 | 18 March 731 to 28 November 741 (10 years+) |  | St Gregory III Papa GREGORIUS Tertius | | Syria | Third pope to bear the same name as his immediate predecessor. |

Status of Christians in Syria

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

Africa

|

Asia

|

|

Europe

|

North America

|

South America

|

Oceania

|

Full list |

Damascus was one of the first regions to receive Christianity during the ministry of St Peter. There were more Christians in Damascus than anywhere else. With the military expansion of the Islamic Umayyad empire into Syria and Anatolia, non-Muslims who retained their native faiths were required to pay a tax (jizya) equivalent to the Islamic Zakat, and were permitted to own land; they were, however, not eligible for Islamic social welfare as Muslims were. [14][15][better source needed]

Damascus still contains a sizeable proportion of Christians, with some churches all over the city, but particularly in the district of Bab Touma (The Gate of Thomas in Aramaic and Arabic). Masses are held every Sunday and civil servants are given Sunday mornings off to allow them to attend church, even though Sunday is a working day in Syria. Schools in Christian-dominated districts have Saturday and Sunday as the weekend, while the official Syrian weekend falls on Friday and Saturday.

During the Syrian civil war, several attacks by Arab or Kurdish Muslims have targeted Syrian Christians, including the 2015 al-Qamishli bombings and the July 2016 Qamishli bombings. In January 2016, YPG militias conducted a surprise attack on Assyrian checkpoints in Qamishli, in a predominantly Assyrian area, killing one Assyrian and wounding three others.[16][17][18]

Integration

The old Christian quarter of Jdeydeh, Aleppo

Christians engage in every aspect of Syrian life. Following in the traditions of Paul, who practiced his preaching and ministry in the marketplace, Syrian Christians are participants in the economy, the academic, scientific, engineering, arts, and intellectual life, entertainment, and the Politics of Syria. Many Syrian Christians are public sector and private sector managers and directors, while some are local administrators, members of Parliament, and ministers in the government. A number of Syrian Christians are also officers in the armed forces of Syria. They have preferred to mix in with Muslims rather than form all-Christian units and brigades, and fought alongside their Muslim compatriots against Israeli forces in the various Arab–Israeli conflicts of the 20th century. In addition to their daily work, Syrian Christians also participate in volunteer activities in the less developed areas of Syria. As a result, Syrian Christians are generally viewed by other Syrians as an asset to the larger community.

In September 2017, the deputy Hammouda Sabbagh, christian and member of the Ba'ath Party, is elected speaker of parliament with 193 votes on 252.[19]

Separation

Syrian Christians are more urbanized than Muslims; many live either in or around Aleppo, Hamah, or Latakia. In the 18th century, Christians were relatively wealthier than Muslims in Aleppo.[20][21] Syrian Christians have their own courts that deal with civil cases like marriage, divorce and inheritance based on Bible teachings. By agreement with other communities, Syrian Christian churches do not proselytise to Muslims and do not accept converts from Islam [citation needed]. Noteworthy Syrian Christians include the chronicler Paul of Aleppo, the chess player Philip Stamma, the Syrian actor Bassem Yakhour and the Syrian Armenian musician George Tutunjian.

The Constitution of Syria states that the President of Syria has to be a Muslim; this was as a result of popular demand at the time the constitution was written. However, Syria does not profess a state religion.

On 31 January 1973, Hafez al-Assad implemented the new constitution (after reaching power through a military coup in 1970), which led to a national crisis. Unlike previous constitutions, this one did not require that the president of Syria to be of the Islamic faith, leading to fierce demonstrations in Hama, Homs and Aleppo organized by the Muslim Brotherhood and the ulama. They labeled Assad as the "enemy of Allah" and called for a jihad against his rule.[22]Robert D. Kaplan has compared Assad's coming to power to "an untouchable becoming maharajah in India or a Jew becoming tsar in Russia—an unprecedented development shocking to the Sunni majority population which had monopolized power for so many centuries."[23]

The government survived a series of armed revolts by Islamists, mainly members of the Muslim Brotherhood, from 1976 until 1982.

Christian cities/areas

Significant Christian populations.

Christians spread throughout Syria and have sizable populations in some cities/areas; important cities/areas are:

Aleppo – has the largest Christian population of various denominations (mostly ethnic Armenians and Assyrian/Syriac. Also members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch and Melkite Catholic Church)

Damascus – contains a sizable Christian communities of all Christian denominations represented in the country.

Homs – has the second largest Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Wadi Al-Nasarah or Valley of Christians – has a sizable Christian population in the area (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Safita - has a sizable Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Ma'loula – has a sizable Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch and Melkite Catholic Church)

Saidnaya – has a sizable Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Al-Suqaylabiyah – has a predominantly Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Mhardeh – has a predominantly Christian population

Tartous – has a sizable Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Latakia – has a sizable Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Suwayda – has a sizable Christian population (mostly members of Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch)

Al-Hasakah – has a large ethnic Assyrian/Syriac population.

Qamishli – has a large ethnic Assyrian/Syriac population.

Khabur River – 35 villages has a large ethnic Assyrian/Syriac population.

Syrian Christians during the Syrian Civil War

Syrian Christians like most Syrian citizens have been badly affected by the Syrian Civil War. According to Syrian law, all Syrian men of adult age with brothers are eligible for military conscription, including Christians.[24]

Since the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, 300,000 to 900,000 Christians have left the country,[25][needs update] but as the situation began to stabilize in 2017 following recent army gains, return of electricity and water to many areas and stability returning to many government controlled regions, some Christians began returning to Syria, most notably in the city of Homs.[26][additional citation(s) needed]

Notable Christians

Hammouda Sabbagh Speaker of the People's Council of Syria since 2017

Ibrahim Haddad Minister of Oil and Mineral Reserves (2001-2006)

Fares al-Khoury Prime Minister of Syria (1944-1945) and (1954-1955)

Mikhail Wehbe Permanent Representative of Syria to the United Nations (1996-2003)

See also

- Persecution of Christians by ISIL

- Religion in Syria

- List of monasteries in Syria

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Syria

- Roman Catholicism in Syria

- List of churches in Aleppo

- St Baradates

- Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian Civil War

Notes

^ ab CIA World Factbook, People and Society: Syria

^ Gulf/2000 Project (2018). "Syria Religious Composition 2018". Columbia University - School of International and Public Affairs..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Bailey, Betty Jane; Bailey, J. Martin (2003). Who Are the Christians in the Middle East?. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. p. 191. ISBN 0-8028-1020-9.

^ "Syria". State.gov. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

^ Syria: US State Department The July–December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report

^ Hitti, Philip (2005) [1924]. The Syrians in America. Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-176-2.

^ Lage- und Tätigkeitsbericht des Gustav-Adolf-Werkes für das Jahr 2013/14 Diasporawerk der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland (GAW yearly report, in German)

^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 14. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

^ John Platts. A new universal biography, containing interesting accounts. p. 479.

^ Archibald Bower, Samuel Hanson Cox. The History of the Popes: From the Foundation of the See of Rome to A.D. 1758; with an Introd. and a Continuation to the Present Time, Volume 2. p. 14.

^ John Platts. A New Universal Biography: Forming the first volume of series. p. 483.

^ Pierre Claude François Daunou. The Power of the Popes. p. 352.

^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/535547/Saint-Sergius-I

^ al-Jawziyyah, Ibn Qayyim (2008). Ahkam Ahl al-Dhimmah. 1. Beirut: Dar Ibn Hazm. p. 121. Retrieved 2016-05-12.

^ "Rules of Dhimmitude". Dhimmitude.org. Retrieved 2016-05-12..

^ http://www.aina.org/news/20160112034707.htm

^ https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/revisiting-kurdish-tolerance-ypg-attacks-assyrian-militia/

^ http://aa.com.tr/en/politics/syrias-christians-pressured-by-forced-pyd-assimilation/541614

^ http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/2017/09/28/97001-20170928FILWWW00222-un-chretien-elu-a-la-tete-du-parlement-syrien.php

^ Saint Terzia Church in Aleppo Christians in Aleppo (in Arabic)

^ BBC News Guide: Christians in the Middle East, last update 15 December 2005.

^ Alianak, Sonia (2007). Middle Eastern Leaders and Islam: A Precarious Equilibrium. Peter Lang. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8204-6924-9.

^ Kaplan, Robert (February 1993). "Syria: Identity Crisis". The Atlantic.

^ [1]

^ http://www.aina.org/reports/utrmcfsi.pdf

^ Syria: Homs Christians return to rebuild homes and lives - World Watch Monitor

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

External links

- European Centre for Law and Justice (2011): The Persecution of Oriental Christians, what answer from Europe?