Stamen

Stamens of a Hippeastrum with white filaments and prominent anthers carrying pollen

The stamen (plural stamina or stamens) is the pollen-producing reproductive organ of a flower. Collectively the stamens form the androecium.[1]

Contents

1 Morphology and terminology

2 Etymology

3 Variation in morphology

4 Pollen production

5 Sexual reproduction in plants

6 Descriptive terms

7 References

8 Bibliography

9 External links

Morphology and terminology

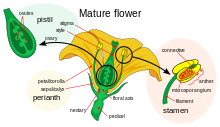

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament and an anther which contains microsporangia. Most commonly anthers are two-lobed and are attached to the filament either at the base or in the middle area of the anther. The sterile tissue between the lobes is called the connective. A pollen grain develops from a microspore in the microsporangium and contains the male gametophyte.

The stamens in a flower are collectively called the androecium. The androecium can consist of as few as one-half stamen (i.e. a single locule) as in Canna species or as many as 3,482 stamens which have been counted in Carnegiea gigantea.[2] The androecium in various species of plants forms a great variety of patterns, some of them highly complex.[3][4][5][6] It generally surrounds the gynoecium and is surrounded by the perianth. A few members of the family Triuridaceae, particularly Lacandonia schismatica, are exceptional in that their gynoecia surround their androecia.

Hippeastrum flowers showing stamens above the style (with its terminal stigma)

Closeup of stamens and stigma of Lilium 'Stargazer'

Etymology

Stamen is the Latin word meaning "thread" (originally thread of the warp, in weaving).[7]

Filament derives from classical Latin filum, meaning "thread"[7]

Anther derives from French anthère,[8] from classical Latin anthera, meaning "medicine extracted from the flower"[9][10] in turn from Ancient Greek ἀνθηρά,[8][10] feminine of ἀνθηρός, "flowery",[11] from ἄνθος,[8] "flower"[11]

Androecium derives from Ancient Greek ἀνήρ meaning "man",[11] and οἶκος meaning "house" or "chamber/room".[11]

Variation in morphology

Stamens, with distal anther attached to the filament stalk, in context of floral anatomy

Depending on the species of plant, some or all of the stamens in a flower may be attached to the petals or to the floral axis. They also may be free-standing or fused to one another in many different ways, including fusion of some but not all stamens. The filaments may be fused and the anthers free, or the filaments free and the anthers fused. Rather than there being two locules, one locule of a stamen may fail to develop, or alternatively the two locules may merge late in development to give a single locule.[12] Extreme cases of stamen fusion occur in some species of Cyclanthera in the family Cucurbitaceae and in section Cyclanthera of genus Phyllanthus (family Euphorbiaceae) where the stamens form a ring around the gynoecium, with a single locule.[13]

Cross section of a Lilium stamen, with four locules surrounded by the tapetum

Pollen production

A typical anther contains four microsporangia. The microsporangia form sacs or pockets (locules) in the anther (anther sacs or pollen sacs). The two separate locules on each side of an anther may fuse into a single locule. Each microsporangium is lined with a nutritive tissue layer called the tapetum and initially contains diploid pollen mother cells. These undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. The spores may remain attached to each other in a tetrad or separate after meiosis. Each microspore then divides mitotically to form an immature microgametophyte called a pollen grain.

The pollen is eventually released when the anther forms openings (dehisces). These may consist of longitudinal slits, pores, as in the heath family (Ericaceae), or by valves, as in the barberry family (Berberidaceae). In some plants, notably members of Orchidaceae and Asclepiadoideae, the pollen remains in masses called pollinia, which are adapted to attach to particular pollinating agents such as birds or insects. More commonly, mature pollen grains separate and are dispensed by wind or water, pollinating insects, birds or other pollination vectors.

Pollen of angiosperms must be transported to the stigma, the receptive surface of the carpel, of a compatible flower, for successful pollination to occur. After arriving, the pollen grain (an immature microgametophyte) typically completes its development. It may grow a pollen tube and undergoing mitosis to produce two sperm nuclei.

Sexual reproduction in plants

Stamen with pollinia and its anther cap. Phalaenopsis orchid.

In the typical flower (that is, in the majority of flowering plant species) each flower has both carpels and stamens. In some species, however, the flowers are unisexual with only carpels or stamens. (monoecious = both types of flowers found on the same plant; dioecious = the two types of flower found only on different plants). A flower with only stamens is called androecious. A flower with only carpels is called gynoecious.

A flower having only functional stamens and lacking functional carpels is called a staminate flower, or (inaccurately) male.[14] A plant with only functional carpels is called pistillate, or (inaccurately) female.[14]

An abortive or rudimentary stamen is called a staminodium or staminode, such as in Scrophularia nodosa.

The carpels and stamens of orchids are fused into a column. The top part of the column is formed by the anther, which is covered by an anther cap.

Descriptive terms

Scanning electron microscope image of Pentas lanceolata anthers, with pollen grains on surface

Lily stamens with prominent red anthers and white filaments

- A column formed from the fusion of multiple filaments is known as an androphore.

The anther can be attached to the filament's connective in two ways:[15]

basifixed: attached at its base to the filament

pseudobasifixed: a somewhat misnomer configuration where connective tissue extends in a tube around the filament

dorsifixed: attached at its center to the filament, usually versatile (able to move)

Stamens can be connate (fused or joined in the same whorl):

extrorse: anther dehiscence directed away from the centre of the flower. Cf. introrse, directed inwards, and latrorse towards the side.[16]

monadelphous: fused into a single, compound structure

declinate: curving downwards, then up at the tip (also – declinate-descending)

diadelphous: joined partially into two androecial structures

pentadelphous: joined partially into five androecial structures

synandrous: only the anthers are connate (such as in the Asteraceae). The fused stamens are referred to as a synandrium.

Stamens can also be adnate (fused or joined from more than one whorl):

epipetalous: adnate to the corolla

epiphyllous: adnate to undifferentiated tepals (as in many Liliaceae)

They can have different lengths from each other:

didymous: two equal pairs

didynamous: occurring in two pairs, a long pair and a shorter pair

tetradynamous: occurring as a set of six stamens with four long and two shorter ones

or respective to the rest of the flower (perianth):

exserted: extending beyond the corolla

included: not extending beyond the corolla

They may be arranged in one of two different patterns:

spiral; or

whorled: one or more discrete whorls (series)

They may be arranged, with respect to the petals:

diplostemonous: in two whorls, the outer alternating with the petals, while the inner is opposite the petals.

obdiplostemonous: in two whorls, the outer opposite the petals

References

^ Beentje, Henk (2010). The Kew Plant Glossary. Richmond, Surrey: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1-84246-422-9..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em, p. 10

^ Charles E. Bessey in SCIENCE Vol. 40 (November 6, 1914) p. 680.

^ Sattler, R. 1973. Organogenesis of Flowers. A Photographic Text-Atlas. University of Toronto Press.

ISBN 0-8020-1864-5.

^ Sattler, R. 1988. A dynamic multidimensional approach to floral morphology. In: Leins, P., Tucker, S. C. and Endress, P. (eds) Aspects of Floral Development. J. Cramer, Berlin, pp. 1-6.

ISBN 3-443-50011-0

^ Greyson, R. I. 1994. The Development of Flowers. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-506688-X.

^ Leins, P. and Erbar, C. 2010. Flower and Fruit. Schweizerbart Science Publishers, Stuttgart.

ISBN 978-3-510-65261-7.

^ ab Lewis, C.T. & Short, C. (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

^ abc Klein, E. (1971). A comprehensive etymological dictionary of the English language. Dealing with the origin of words and their sense development thus illustration the history of civilization and culture. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

^ Siebenhaar, F.J. (1850). Terminologisches Wörterbuch der medicinischen Wissenschaften. (Zweite Auflage). Leipzig: Arnoldische Buchhandlung.

^ ab Saalfeld, G.A.E.A. (1884). Tensaurus Italograecus. Ausführliches historisch-kritisches Wörterbuch der Griechischen Lehn- und Fremdwörter im Lateinischen. Wien: Druck und Verlag von Carl Gerold's Sohn, Buchhändler der Kaiserl. Akademie der Wissenschaften.

^ abcd Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

^ Goebel, K.E.v. (1969) [1905]. Organography of plants, especially of the Archegoniatae and Spermaphyta. Part 2 Special organography. New York: Hofner publishing company. pages 553–555

^ Rendle, A.B. (1925). The Classification of Flowering Plants. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521060578.

^ ab Encyclopædia Britannica.com

^ Hickey, M.; King, C. (1997). Common Families of Flowering Plants. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521576093.

^ William G. D'Arcy, Richard C. Keating (eds.) The Anther: Form, Function, and Phylogeny. Cambridge University Press, 1996

ISBN 9780521480635

Rendle, Alfred Barton (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 553–573.

Rendle, Alfred Barton (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 553–573.

Bibliography

Simpson, Michael G. (2011). "Androecium". Plant Systematics. Academic Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-08-051404-8. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

Weberling, Focko (1992). "1.5 The Androecium". Morphology of Flowers and Inflorescences (trans. Richard J. Pankhurst). CUP Archive. p. 93. ISBN 0-521-43832-2. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

External links

| Look up Androecium, Anther, Filament, Gynoecium, or Stamen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Stamen and anther (category) |