Dyrosauridae

- Not to be confused with Dryosauridae

| Dyrosauridae Temporal range: 70–35 Ma PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

| |

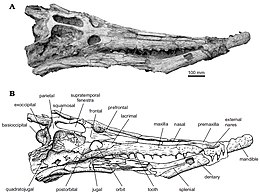

| Skull of the dyrosaurid Arambourgisuchus khouribgaensis | |

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Suborder: | †Tethysuchia |

| Family: | †Dyrosauridae de Stefano, 1903 |

| Genera | |

See below | |

Dyrosauridae is a family of extinct neosuchian crocodyliforms that lived from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) to the Eocene. Dyrosaurid fossils are globally distributed, having been found in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America. Over a dozen species are currently known, varying greatly in overall size and cranial shape. All were presumably aquatic, with species inhabiting both freshwater and marine environments. Ocean-dwelling dyrosaurids were among the few marine reptiles to survive the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

Contents

1 Paleobiogeography

2 General

3 Phylogeny

4 Palaeobiology

4.1 Habitat

4.2 Reproduction

5 References

6 External links

Paleobiogeography

Dyrosaurids were once considered an African group, but discoveries made starting from the 2000s indicate they inhabited the majority of the continents.[1] In fact, basal forms suggest that their cradle may have been North America.

General

| Genus | Status | Age | Location | Description | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Acherontisuchus | Valid | Paleocene | A large-bodied, long-snouted freshwater dyrosaurid from the Cerrejón Formation | ||

Anthracosuchus | Valid | Paleocene | A short-snouted freshwater dyrosaurid from the Cerrejón Formation | ||

Arambourgisuchus | Valid | Paleocene | A long-snouted marine dyrosaurid | ||

Atlantosuchus | Valid | Paleocene | A long-snouted marine dyrosaurid with the longest snout length in proportion to body size of any dyrosaurid | ||

Cerrejonisuchus | Valid | Paleocene | A small-bodied, short-snouted freshwater dyrosaurid from the Cerrejón Formation | ||

Chenanisuchus | Valid | Maastrichtian-Paleocene | The genus spans the K-Pg boundary |  | |

Congosaurus | Valid | Paleocene | |||

Dyrosaurus | Valid | Eocene | A large-bodied, long-snouted marine dyrosaurid |  | |

Guarinisuchus | Valid | Paleocene | A marine dyrosaurid |  | |

Hyposaurus | Valid | Maastrichtian-Paleocene | Five species have been named, the most of any dyrosaurid genus; the genus spans the K-Pg boundary | ||

Phosphatosaurus | Valid | Eocene | A large-bodied, long-snouted marine dyrosaurid with blunt teeth and a spoon-shaped snout tip | ||

Rhabdognathus | Valid | Maastrichtian-Paleogene | A large-bodied, long-snouted marine dyrosaurid; the genus spans the K-Pg boundary | ||

Sokotosaurus | Junior synonym | Junior synonym of Hyposaurus | |||

Sokotosuchus | Valid | Maastrichtian | A long-snouted marine dyrosaurid | ||

Tilemsisuchus | Valid | Eocene |

Phylogeny

Jouve et al. (2005) diagnose Dyrosauridae as a clade based on the following seven synapomorphies or shared characters:

- Posteromedial wing of the retroarticular process dorsally situated ventrally on the retroarticular process

- Occipital tuberosities small

Exoccipital participates largely to the occipital condyle- Supratemporal fenestra anteroposteriorly strongly elongated

- Symphysis about as wide as high

- Quadratojugal participates largely to the cranial condyle for articulation with the jaw

- 4 premaxillary teeth

Below is a cladogram after Jouve et al. (2005) showing phylogenetic relationships of Dyrosauridae and other closely related neosuchians:

.mw-parser-output table.cladeborder-spacing:0;margin:0;font-size:100%;line-height:100%;border-collapse:separate;width:auto.mw-parser-output table.clade table.cladewidth:100%.mw-parser-output table.clade tdborder:0;padding:0;vertical-align:middle;text-align:center.mw-parser-output table.clade td.clade-labelwidth:0.8em;border:0;padding:0 0.2em;vertical-align:bottom;text-align:center.mw-parser-output table.clade td.clade-slabelborder:0;padding:0 0.2em;vertical-align:top;text-align:center.mw-parser-output table.clade td.clade-barvertical-align:middle;text-align:left;padding:0 0.5em.mw-parser-output table.clade td.clade-leafborder:0;padding:0;text-align:left;vertical-align:middle.mw-parser-output table.clade td.clade-leafRborder:0;padding:0;text-align:right

| Neosuchia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Composite cladogram for Dyrosauridae (from Jouve et al. 2008 and Barbosa et al. 2008):

Dyrosauridae |

Dyrosauridae incertae sedis: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Cladogram after Hastings et al. (2011) showing geographic occurrences of taxa:[2]

| Neosuchia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Analysis suggest that the closest relatives of dyrosaurids are Sarcosuchus and Terminonaris.

Palaeobiology

Habitat

Most dyrosaurids were marine crocodiles. Dyrosaurids found from what is now northern and western Africa are thought to have inhabited the Trans-Saharan Sea, an epicontenental seaway that covered low-lying basins that formed during the late Mesozoic breakup of Africa and South America through crustal attenuation and fault reactivation, during a time of great global sea level elevation.[3][4]

Dyrosaurids have also been found from nonmarine sediments. In northern Sudan, dyrosaurids are known from fluvial deposits, indicating that they lived in a river setting.[5] Bones from indeterminate dyrosaurids have been found in inland deposits in Pakistan as well. Some dyrosaurids, such as those from the Umm Himar Formation in Saudi Arabia, inhabited estuarine environments near the coast. The recently named dyrosaurids Cerrejonisuchus and Acherontisuchus have been recovered from the Cerrejón Formation in northwestern Colombia, which is thought to represent a transitional marine-freshwater environment surrounded by rainforest more inland than the estuarine environment of the Umm Himar Formation.[6]Cerrejonisuchus and Acherontisuchus lived in a neotropical setting during a time when global temperatures were much warmer than they are today.[7][8]

Reproduction

In 1978, it was proposed that dyrosaurids lived as adults in the ocean but reproduced in inland freshwater environments. Remains belonging to small-bodied dyrosaurids from Pakistan were interpreted as juveniles. Their presence in inland deposits was viewed as evidence that dyrosaurids hatched far from the ocean.[9] Recently however, the large-bodied and fully mature dyrosaurids of the Cerrejón Formation have shown that some dyrosaurids lived their entire lives in inland environments, never returning to the coast.[2]

References

^ Jouve et al. (2008)

^ ab Hastings, A.K., Bloch, J. and Jaramillo, C.A. (2011). "A new longirostrine dyrosaurid (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of north-eastern Colombia: biogeographic and behavioural implications for new-world dyrosauridae" (PDF). Palaeontology. 54 (5): 1095–116. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01092.x. Retrieved 14 Sep 2011.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link).mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Greigert, J. (1966). "bassin des Iullemmeden". Direction des Mines et de la Géologie, Niger. Publication 2: 1–273.

^ Reyment, R. (1980). "Biogeography of the Saharan Cretaceous and Paleocene epicontinental transgressions". Cretaceous Research. 1 (4): 299–327. doi:10.1016/0195-6671(80)90041-5.

^ Buffetaut, E.; Bussert, R.; Brinkmann, W. (1990). "A new nonmarine vertebrate fauna in the Upper Cretaceous of northern Sudan". Berliner Geowissenschaftlische Abhandlungen. 120: 183–202.

^ Hastings, A. K; Bloch, J. I.; Cadena, E. A.; Jaramillo, C. A. (2010). "A new small short-snouted dyrosaurid (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of northeastern Colombia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 139–162. doi:10.1080/02724630903409204.

^ Head, J. J.; Bloch, J. I.; Hastings, A. K.; Borque, J. R.; Cadena, E. A.; Herrera, F. A.; Polly, P. D.; Jaramillo, C. A. (2009). "Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures". Nature. 457 (7230): 715–717. doi:10.1038/nature07671. PMID 19194448.

^ Kanapaux, B. (February 2, 2010). "UF researchers: Ancient crocodile relative likely food source for Titanoboa". University of Florida News. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

^ Buffetaut, E. (1978). "Crocodilian remains from the Eocene of Pakistan". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 156: 262–283.

- Barbosa, J.A., Kellner, A.W.A. and Viana, M.S.S. (2008). New dyrosaurid crocodylomorph and evidences for faunal turnover at the K–P transition in Brazil. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences: Firstcite

- Buffetaut, E. (1985). L'evolution des crocodiliens. Les animaux disparus-Pour la science, Paris 109.

Jouve, S.; Bouya, B.; Amaghzaz, M. (2008). "A long-snouted dyrosaurid (Crocodyliformes, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of Morocco: phylogenetic and palaeogeographic implications". Palaeontology. 51 (2): 281–294. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00747.x.

Jouve, S.; Iarochène, M.; Bouya, B.; Amaghzaz, M. (2005). "A new dyrosaurid crocodyliform from the Palaeocene of Morocco and a phylogenetic analysis of Dyrosauridae". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50 (3): 581–594.

External links

- Jouve et al. (2005)

- Mikko's Phylogeny Archive Dyrosauridae page

- Paleopedia page on Dyrosauridae