Space Shuttle program

| |

| Country of origin | United States of America |

|---|---|

| Responsible organization | NASA |

| Purpose | Routine Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo transport |

| Status | Completed |

| Program history | |

| Cost | $196 billion (2011) |

| Program duration | 1972–2011 |

| First flight | ALT-12 August 12, 1977 |

| First crewed flight | STS-1 April 12, 1981 |

| Last flight | STS-135 July 21, 2011 |

| Successes | 133 |

| Failures | 2 Challenger (launch failure, 7 fatalities), Columbia (re-entry failure, 7 fatalities) |

| Launch site(s) | LC-39, Kennedy Space Center |

| Vehicle information | |

| Vehicle type | Reusable space plane |

| Crew vehicle | Space Shuttle orbiter |

| Crew capacity | 8 (emergency: 11) |

| Launch vehicle(s) | Space Shuttle stack |

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| Space policy of the United States |

|---|

|

|

US manned space programs

|

US space probes

|

Expendable launch vehicles

|

Notable figures

|

Astronauts

|

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. Its official name, Space Transportation System (STS), was taken from a 1969 plan for a system of reusable spacecraft of which it was the only item funded for development.[1]

The Space Shuttle—composed of an orbiter launched with two reusable solid rocket boosters and a disposable external fuel tank—carried up to eight astronauts and up to 50,000 lb (23,000 kg) of payload into low Earth orbit (LEO). When its mission was complete, the orbiter would re-enter the Earth's atmosphere and land like a glider at either the Kennedy Space Center or Edwards Air Force Base.

The Shuttle is the only winged manned spacecraft to have achieved orbit and landing, and the only reusable manned space vehicle that has ever made multiple flights into orbit (the Russian shuttle Buran was very similar and was designed to have the same capabilities but made only one unmanned spaceflight before it was cancelled). Its missions involved carrying large payloads to various orbits (including segments to be added to the International Space Station (ISS)), providing crew rotation for the space station, and performing service missions. The orbiter also recovered satellites and other payloads (e.g., from the ISS) from orbit and returned them to Earth, though its use in this capacity was rare. Each vehicle was designed with a projected lifespan of 100 launches, or 10 years' operational life, though original selling points on the shuttles were over 150 launches and over a 15-year operational span with a 'launch per month' expected at the peak of the program, but extensive delays in the development of the International Space Station[2] never created such a peak demand for frequent flights.

Contents

1 Background

2 Conception and development

3 Program history

4 Accomplishments

5 Budget

6 Accidents

6.1 Challenger 1986

6.2 Columbia 2003

7 Retirement

8 Preservations

9 Passenger modules

10 Successors

11 Assets and transition plan

12 Critiques

13 Support vehicles

14 See also

15 References

16 Further reading

17 External links

Background

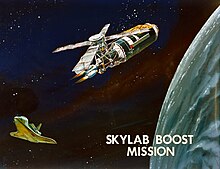

Various shuttle concepts had been explored since the late 1960s. The program formally commenced in 1972, becoming the sole focus of NASA's manned operations after the Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo-Soyuz programs in 1975. The Shuttle was originally conceived of and presented to the public in 1972 as a 'Space Truck' which would, among other things, be used to build a United States space station in low Earth orbit during the 1980s and then be replaced by a new vehicle by the early 1990s. The stalled plans for a U.S. space station evolved into the International Space Station and were formally initiated in 1983 by President Ronald Reagan, but the ISS suffered from long delays, design changes and cost over-runs[2] and forced the service life of the Space Shuttle to be extended several times until 2011 when it was finally retired—serving twice as long than it was originally designed to do. In 2004, according to President George W. Bush's Vision for Space Exploration, use of the Space Shuttle was to be focused almost exclusively on completing assembly of the ISS, which was far behind schedule at that point.

The first experimental orbiter Enterprise was a high-altitude glider, launched from the back of a specially modified Boeing 747, only for initial atmospheric landing tests (ALT). Enterprise's first test flight was on February 18, 1977, only five years after the Shuttle program was formally initiated; leading to the launch of the first space-worthy shuttle Columbia on April 12, 1981 on STS-1. The Space Shuttle program finished with its last mission, STS-135 flown by Atlantis, in July 2011, retiring the final Shuttle in the fleet. The Space Shuttle program formally ended on August 31, 2011.[3]

Conception and development

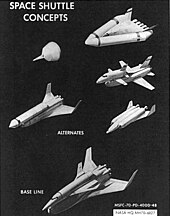

North American Rockwell's initial shuttle design. The original, fully reusable concept used a piloted, winged booster stage, essentially a larger version of the orbiter stage.

Before the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, NASA began early studies of space shuttle designs. In 1969, President Richard Nixon formed the Space Task Group, chaired by Vice President Spiro Agnew. This group outlined ambitious post-Apollo missions centered on a large permanently manned space station, a small reusable logistics vehicle that would support it, and ultimately a manned mission to Mars. Smaller goals included a variety of space vehicles for moving spacecraft around in orbit.[4]

Presenting the plans to Nixon, Agnew was told that the administration would not commit to a Mars mission, and limited activity to low Earth orbit for the immediate future.[5] He was then told to select one of the two remaining proposals. After some debate between the station and the vehicle, the vehicle was chosen; suitably designed, such a spacecraft could perform some longer-duration missions and thus fill some of the goals of the station, and over the longer run, could help lower the cost of access to space and make the station less expensive.[4]

The goal, as presented by NASA to Congress, was to provide a much less-expensive means of access to space that would be used by NASA, the Department of Defense, and other commercial and scientific users.[6]

During early shuttle development there was great debate about the optimal shuttle design that best balanced capability, development cost and operating cost. Ultimately chosen was a design using a reusable winged orbiter, reusable solid rocket boosters, and an expendable external fuel tank for the orbiter's main engines.[4]

The shuttle program was formally launched on January 5, 1972, when President Nixon announced that NASA would proceed with the development of a reusable space shuttle system.[4] The stated goals of "transforming the space frontier...into familiar territory, easily accessible for human endeavor"[7] was to be achieved by launching as many as 50 missions per year, with hopes of driving down per-mission costs.[8]

The prime contractor for the program was North American Rockwell (later Rockwell International, now Boeing), the same company responsible for building the Apollo Command/Service Module. The contractor for the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters was Morton Thiokol (now part of Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems), for the external tank, Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin), and for the Space Shuttle main engines, Rocketdyne (now Aerojet Rocketdyne).[4]

The first orbiter was originally planned to be named Constitution, but a massive write-in campaign from fans of the Star Trek television series convinced the White House to change the name to Enterprise.[9] Amid great fanfare, Enterprise (designated OV-101) was rolled out on September 17, 1976, and later conducted a successful series of glide-approach and landing tests in 1977 that were the first real validation of the design.[10]

Early U.S. space shuttle concepts. |  STS-1 at liftoff. The External Tank was painted white for the first two Space Shuttle launches. From STS-3 on, it was left unpainted.[citation needed] . The first two missions had tanks painted white, this elimination saved some weight (about 600 lbs / 272 kg).[11] Decades later some questioned if the paint might have prevented the ice-soaked foam shedding issue that lead to the destruction of Columbia.[11] |  It was originally hoped that the Shuttle Program might be able to rejuvenate Skylab, but the Shuttle was not yet ready to fly when Skylab re-entered Earth's atmosphere —partially because higher than expected solar activity caused accelerated decay of Skylab's orbit. |  Artistic illustration of shuttle processing |  Endeavour in orbit, 2002 |

Program history

President Nixon (right) with NASA Administrator Fletcher in January 1972, three months before Congress approved funding for the Shuttle program

Shuttle approach and landing test crews, 1976

All Space Shuttle missions were launched from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC).[12] The weather criteria used for launch included, but were not limited to: precipitation, temperatures, cloud cover, lightning forecast, wind, and humidity.[13] The Shuttle was not launched under conditions where it could have been struck by lightning.

The first fully functional orbiter was Columbia (designated OV-102), built in Palmdale, California. It was delivered to Kennedy Space Center (KSC) on March 25, 1979, and was first launched on April 12, 1981—the 20th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's space flight—with a crew of two.

Challenger (OV-099) was delivered to KSC in July 1982, Discovery (OV-103) in November 1983, Atlantis (OV-104) in April 1985 and Endeavour in May 1991. Challenger was originally built and used as a Structural Test Article (STA-099), but was converted to a complete orbiter when this was found to be less expensive than converting Enterprise from its Approach and Landing Test configuration into a spaceworthy vehicle.

On April 24, 1990, Discovery carried the Hubble Space Telescope into space during STS-31.

In the course of 135 missions flown, two orbiters (Columbia and Challenger) suffered catastrophic accidents, with the loss of all crew members, totaling 14 astronauts.

The accidents led to national level inquiries and detailed analysis of why the accidents occurred.[11] There was a significant pause where changes were made before the Shuttles returned to flight.[11] The Columbia disaster occurred in 2003, but STS took more than a year off before returning to flight in June 2005 with the STS-114 mission.[11] The previous break was between January 1986 (when the Challenger disaster occurred) and 32 months later when STS-26 was launched on September 29, 1988.[14]

The longest Shuttle mission was STS-80 lasting 17 days, 15 hours. The final flight of the Space Shuttle program was STS-135 on July 8, 2011.

Since the Shuttle's retirement in 2011, many of its original duties are performed by an assortment of government and private vessels. The European ATV Automated Transfer Vehicle supplied the ISS between 2008 and 2015. Classified military missions are being flown by the US Air Force's unmanned space plane, the X-37B[citation needed]. By 2012, cargo to the International Space Station was already being delivered commercially under NASA's Commercial Resupply Services by SpaceX's partially reusable Dragon spacecraft, followed by Orbital Sciences' Cygnus spacecraft in late 2013. Crew service to the ISS is currently provided by the Russian Soyuz while work on the Commercial Crew Development program proceeds; the first crewed flight of this is planned for January 27, 2019, on the SpaceX Falcon 9 with Dragon 2 crew capsule.[15] For missions beyond low Earth orbit, NASA is building the Space Launch System and the Orion (spacecraft).

NASA Administrator address the crowd at the Spacelab arrival ceremony in February 1982. On the podium with him is then-Vice President George Bush, the director general of European Space Agency (ESA), Eric Quistgaard, and director of Kennedy Space Center Richard G. Smith |  "President Ronald Reagan chats with NASA astronauts Henry Hartsfield and Thomas Mattingly on the runway as first lady Nancy Reagan scans the nose of Space Shuttle Columbia following its Independence Day landing at Edwards Air Force Base on July 4, 1982."[16] |  STS-3 lands in March 1982 |

Accomplishments

Galileo floating free in space after release from Space Shuttle Atlantis, 1989

Space Shuttle Endeavour docked with the International Space Station (ISS), 2011

Space Shuttle missions have included:

Spacelab missions[17] Including:- Science[17]

- Astronomy[17]

- Crystal growth[17]

- Space physics[17]

- Construction of the International Space Station (ISS)

- Crew rotation and servicing of Mir and the International Space Station (ISS)

- Servicing missions, such as to repair the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and orbiting satellites

- Manned experiments in low Earth orbit (LEO)

- Carried to low Earth orbit (LEO):

- The Hubble Space Telescope (HST)

- Components of the International Space Station (ISS)

- Supplies in Spacehab modules or Multi-Purpose Logistics Modules

- The Long Duration Exposure Facility

- The Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite

- The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory

- The Earth Radiation Budget Satellite

- The Mir Shuttle Docking Node

- Carried satellites with a booster, such as the Payload Assist Module (PAM-D) or the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), to the point where the booster sends the satellite to:

- A higher Earth orbit; these have included:

- Chandra X-ray Observatory

- The first six TDRS satellites

- Two DSCS-III (Defense Satellite Communications System) communications satellites in one mission

- A Defense Support Program satellite

- An interplanetary mission; these have included:

- Magellan

- Galileo

- Ulysses

- A higher Earth orbit; these have included:

U.S. Shuttle Columbia landing at the end of STS-73, 1995 |  Space art for the Spacelab 2 mission, showing some of the various experiments in the payload bay. Spacelab was a major European contribution to the Space Shuttle Program |  European astronauts prepare for their Spacelab mission, 1984. |  SpaceLab hardware included a pressurized lab, but also other equipment allowing the Orbiter to serve as a manned space observatory (Astro-2 mission, 1995, shown) |  Astronauts Thomas D. Akers and Kathryn C. Thornton install corrective optics on the Hubble Space Telescope during STS-61. |

Budget

Space Shuttle Atlantis takes flight on the STS-27 mission on December 2, 1988. The Shuttle takes about 8.5 minutes to accelerate to a speed of over 27,000 km/h (17000 mph) and achieve orbit.

A drag chute is deployed by Endeavour as it completes a mission of almost 17 days in space on Runway 22 at Edwards Air Force Base in southern California. Landing occurred at 1:46 pm (EST), March 18, 1995.

Early during development of the space shuttle, NASA had estimated that the program would cost $7.45 billion ($43 billion in 2011 dollars, adjusting for inflation) in development/non-recurring costs, and $9.3M ($54M in 2011 dollars) per flight.[18] Early estimates for the cost to deliver payload to low earth orbit were as low as $118 per pound ($260/kg) of payload ($635/lb or $1,400/kg in 2011 dollars), based on marginal or incremental launch costs, and assuming a 65,000 pound (30 000 kg) payload capacity and 50 launches per year.[19][20] A more realistic projection of 12 flights per year for the 15-year service life combined with the initial development costs would have resulted in a total cost projection for the program of roughly $54 billion (in 2011 dollars).

The total cost of the actual 30-year service life of the shuttle program through 2011, adjusted for inflation, was $196 billion.[8] The exact breakdown into non-recurring and recurring costs is not available, but, according to NASA, the average cost to launch a Space Shuttle as of 2011 was about $450 million per mission.[21]

NASA's budget for 2005 allocated 30%, or $5 billion, to space shuttle operations;[22] this was decreased in 2006 to a request of $4.3 billion.[23] Non-launch costs account for a significant part of the program budget: for example, during fiscal years 2004 to 2006, NASA spent around $13 billion on the space shuttle program,[24] even though the fleet was grounded in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster and there were a total of three launches during this period of time. In fiscal year 2009, NASA budget allocated $2.98 billion for 5 launches to the program, including $490 million for "program integration", $1.03 billion for "flight and ground operations", and $1.46 billion for "flight hardware" (which includes maintenance of orbiters, engines, and the external tank between flights.)

Per-launch costs can be measured by dividing the total cost over the life of the program (including buildings, facilities, training, salaries, etc.) by the number of launches. With 135 missions, and the total cost of US$192 billion (in 2010 dollars), this gives approximately $1.5 billion per launch over the life of the shuttle program.[25] A 2017 study found that carrying one kilogram of cargo to the ISS on the shuttle cost $272,000 in 2017 dollars, twice the cost of Cygnus and three times that of Dragon.[26]

NASA used a management philosophy known as success-oriented management during the Space Shuttle program which was described by historian Alex Roland in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster as "hoping for the best".[27] Success-oriented management has since been studied by several analysts in the area.[28][29][30]

Accidents

In 1986, Challenger disintegrated one minute and 13 seconds after liftoff.

Play media

Play mediaVideo of Columbia's final moments, filmed by the crew.

Space Shuttle Discovery as it approaches the International Space Station during STS-114 on July 28, 2005. This was the Shuttle's return to flight mission after the Columbia disaster

In the course of 135 missions flown, two orbiters were destroyed, with loss of crew totalling 14 astronauts:

Challenger – lost 73 seconds after liftoff, STS-51-L, January 28, 1986

Columbia – lost approximately 16 minutes before its expected landing, STS-107, February 1, 2003

There was also one abort-to-orbit and some fatal accidents on the ground during launch preparations.

Challenger 1986

Close-up video footage of Challenger during its final launch on January 28, 1986 clearly show it began due to an O-ring failure on the right solid rocket booster (SRB). The hot plume of gas leaking from the failed joint caused the collapse of the external tank, which then resulted in the orbiter's disintegration due to high aerodynamic stress. The accident resulted in the loss of all seven astronauts on board. Endeavour (OV-105) was built to replace Challenger (using structural spare parts originally intended for the other orbiters) and delivered in May 1991; it was first launched a year later.

After the loss of Challenger, NASA grounded the shuttle program for over two years, making numerous safety changes recommended by the Rogers Commission Report, which included a redesign of the SRB joint that failed in the Challenger accident. Other safety changes included a new escape system for use when the orbiter was in controlled flight, improved landing gear tires and brakes, and the reintroduction of pressure suits for shuttle astronauts (these had been discontinued after STS-4; astronauts wore only coveralls and oxygen helmets from that point on until the Challenger accident). The shuttle program continued in September 1988 with the launch of Discovery on STS-26.

The accidents did not just affect the technical design of the orbiter, but also NASA.[14]

Quoting some recommendations made by the post-Challenger Rogers commission:[14]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Recommendation I – The faulty Solid Rocket Motor joint and seal must be changed. This could be a new design eliminating the joint or a redesign of the current joint and seal. ... the Administrator of NASA should request the National Research Council to form an independent Solid Rocket Motor design oversight committee to implement the Commission's design recommendations and oversee the design effort.

Recommendation II – The Shuttle Program Structure should be reviewed. ... NASA should encourage the transition of qualified astronauts into agency management Positions.

Recommendation III – NASA and the primary shuttle contractors should review all Criticality 1, 1R, 2, and 2R items and hazard analyses.

Recommendation IV – NASA should establish an Office of Safety, Reliability and Quality Assurance to be headed by an Associate Administrator, reporting directly to the NASA Administrator.

Recommendation VI – NASA must take actions to improve landing safety. The tire, brake and nosewheel system must be improved.

Recommendation VII – Make all efforts to provide a crew escape system for use during controlled gliding flight.

Recommendation VIII – The nation's reliance on the shuttle as its principal space launch capability created a relentless pressure on NASA to increase the flight rate ... NASA must establish a flight rate that is consistent with its resources.

Columbia 2003

The shuttle program operated accident-free for seventeen years after the Challenger disaster, until Columbia broke up on re-entry, killing all seven crew members, on February 1, 2003. The accident began when a piece of foam shed from the external tank struck the leading edge of the orbiter's left wing, puncturing one of the reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) panels that covered the wing edge and protected it during re-entry. As Columbia re-entered the atmosphere, hot gas penetrated the wing and destroyed it from the inside out, causing the orbiter to lose control and disintegrate.

After the Columbia disaster, the International Space Station operated on a skeleton crew of two for more than two years and was serviced primarily by Russian spacecraft. While the "Return to Flight" mission STS-114 in 2005 was successful, a similar piece of foam from a different portion of the tank was shed. Although the debris did not strike Discovery, the program was grounded once again for this reason.

The second "Return to Flight" mission, STS-121 launched on July 4, 2006, at 14:37 (EDT). Two previous launches were scrubbed because of lingering thunderstorms and high winds around the launch pad, and the launch took place despite objections from its chief engineer and safety head. A five-inch (13 cm) crack in the foam insulation of the external tank gave cause for concern; however, the Mission Management Team gave the go for launch.[31] This mission increased the ISS crew to three. Discovery touched down successfully on July 17, 2006 at 09:14 (EDT) on Runway 15 at Kennedy Space Center.

Following the success of STS-121, all subsequent missions were completed without major foam problems, and the construction of ISS was completed (during the STS-118 mission in August 2007, the orbiter was again struck by a foam fragment on liftoff, but this damage was minimal compared to the damage sustained by Columbia).

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board, in its report, noted the reduced risk to the crew when a shuttle flew to the International Space Station (ISS), as the station could be used as a safe haven for the crew awaiting rescue in the event that damage to the orbiter on ascent made it unsafe for re-entry. The board recommended that for the remaining flights, the shuttle always orbit with the station. Prior to STS-114, NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe declared that all future flights of the shuttle would go to the ISS, precluding the possibility of executing the final Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission which had been scheduled before the Columbia accident, despite the fact that millions of dollars worth of upgrade equipment for Hubble were ready and waiting in NASA warehouses. Many dissenters, including astronauts[who?], asked NASA management to reconsider allowing the mission, but initially the director stood firm. On October 31, 2006, NASA announced approval of the launch of Atlantis for the fifth and final shuttle servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope, scheduled for August 28, 2008. However SM4/STS-125 eventually launched in May 2009.

One impact of Columbia was that future crewed launch vehicles, namely the Ares I, had a special emphasis on crew safety compared to other considerations.[32]

NASA maintains extensive, warehoused catalogs of recovered pieces from the two destroyed orbiters.

Retirement

Atlantis begins the last mission of the Space Shuttle program

The Space Shuttle program was extended several times beyond its originally envisioned 15-year life span because of the delays in building the United States space station in low Earth orbit—a project which eventually evolved into the International Space Station. It was formally scheduled for mandatory retirement in 2010 in accord with the directives President George W. Bush issued on January 14, 2004 in his Vision for Space Exploration.[33]

A$2.5 billion spending provision allowing NASA to fly the Space Shuttle beyond its then-scheduled retirement in 2010 passed the Congress in April 2009, although neither NASA nor the White House requested the one-year extension.[34]

The final Space Shuttle launch was that of Atlantis on July 8, 2011. Although the retirement was planned and roughly in line with what was expected out of STS without further upgrades, the planned replacement for the STS, the Constellation program was cancelled the year before STS concluded. The two programs that took its place, two undetermined commercial crew vehicles and SLS with Orion needed even more time to have a new launcher. NASA has continued to fly to the station via its Roscosmos partner, who still has a functioning manned launcher, the Soyuz system. Manned launch systems have been proposed by other countries, such as the ESA's mini-shuttle Hermes launched by an Ariane rocket, which was cancelled in 1992.

Preservations

Space Shuttle Discovery at the Udvar Hazy museum

Out of the five fully functional shuttle orbiters built, three remain. Enterprise, which was used for atmospheric test flights but not for orbital flight, had many parts taken out for use on the other orbiters. It was later visually restored and was on display at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center until April 19, 2012. Enterprise was moved to New York City in April 2012 to be displayed at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, whose Space Shuttle Pavilion opened on July 19, 2012. Discovery replaced Enterprise at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Atlantis formed part of the Space Shuttle Exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center visitor complex and has been on display there since June 29, 2013 following its refurbishment.[35]

On October 14, 2012, Endeavour completed an unprecedented 12 mi (19 km) drive on city streets from Los Angeles International Airport to the California Science Center, where it has been on display in a temporary hangar since late 2012. The transport from the airport took two days and required major street closures, the removal of over 400 city trees, and extensive work to raise power lines, level the street, and temporarily remove street signs, lamp posts, and other obstacles. Hundreds of volunteers, and fire and police personnel, helped with the transport. Large crowds of spectators waited on the streets to see the shuttle as it passed through the city. Endeavour will be displayed permanently beginning in 2017 at the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center (an addition to the California Science Center currently under construction), where it will be mounted in the vertical position complete with solid rocket boosters and an external tank.[36]

Passenger modules

© Rockwell— host |

Spacehab module

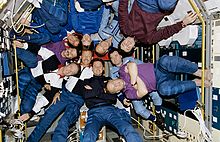

Ten people inside Spacelab Module in the Shuttle bay in June 1995, celebrating the docking of the Space Shuttle and Mir.

One area of Space Shuttle applications is an expanded crew.[37] Crews of up to eight have been flown in the Orbiter, but it could have held at least a crew of ten.[37] Various proposals for filling the payload bay with additional passengers were also made as early as 1979.[38] One proposal by Rockwell provided seating for 74 passengers in the Orbiter payload bay, with support for three days in Earth orbit.[38] With a smaller 64 seat orbiter, costs for the late 1980s would be around 1.5 million USD per seat per launch.[39] The Rockwell passenger module had two decks, four seats across on top and two on the bottom, including a 25-inch (63.5 cm) wide isle and extra storage space.[39]

Another design was Space Habitation Design Associates 1983 proposal for 72 passengers in the Space Shuttle Payload bay.[39] Passengers were located in 6 sections, each with windows and its own loading ramp at launch, and with seats in different configurations for launch and landing.[39] Another proposal was based on the Spacelab habitation modules, which provided 32 seats in the payload bay in addition to those in the cockpit area.[39]

There were some efforts to analyze commercial operation of STS.[40] Using the NASA figure for average cost to launch a Space Shuttle as of 2011 at about $450 million per mission,[21] a cost per seat for a 74[41][42] seat module envisioned by Rockwell came to less than $6 million, not including the regular crew. Some passenger modules used hardware similar to existing equipment, such as the tunnel,[42] which was also needed for Spacehab and Spacelab

Successors

During the three decades of operation, various follow-on and replacements for the STS Space Shuttle were partially developed but not finished.[43]

Examples of possible future space vehicles to supplement or supplant STS:[43]

- Advanced Manned Earth-to-Orbit Vehicle

Shuttle II, Johnson Space Center concept for a follow-on, with 2 boosters and 2 tanks mounted on its wings.[44]- National Aero-Space Plane (NASP)

Rockwell X-30 (not funded)

Lockheed Martin X-33 (cancelled 2001)

Ares I (ended with Constellation cancellation)- Orbital Space Plane Program

One effort in the direction of space transportation was the Reusable Launch Vehicle (RLV) program, initiated in 1994 by NASA.[45] This led to work on the X-33 and X-34 vehicles.[45] NASA spent about 1 billion USD on developing the X-33 hoping for it be in operation by 2005.[45] Another program around the turn of the millennium was the Space Launch Initiative, which was a next generation launch initaive.[46]

The Space Launch Initiative program was started in 2001, and in late 2002 it was evolved into two programs, the Orbital Space Plane Program and the Next Generation Launch Technology program.[46] OSP was oriented towards provided access to the International Space Station.[46]

Other vehicles that would have taken over some of the Shuttles responsibilities were the HL-20 Personnel Launch System or the NASA X-38 of the Crew Return Vehicle program, which were primarily for getting people down from ISS. The X-38 was cancelled in 2002,[47] and the HL-20 was cancelled in 1993.[48] Several other programs in this existed such as the Station Crew Return Alternative Module (SCRAM) and Assured Crew Return Vehicle (ACRV)[49]

According to the 2004 Vision for Space Exploration, the next manned NASA program was to be Project Constellation with its Ares I and Ares V launch vehicles and the Orion Spacecraft; however, the Constellation program was never fully funded, and in early 2010 the Obama administration asked Congress to instead endorse a plan with heavy reliance on the private sector for delivering cargo and crew to LEO.

The Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program began in 2006 with the purpose of creating commercially operated unmanned cargo vehicles to service the ISS.[50] The first of these vehicles, SpaceX's Dragon, became operational in 2012, and the second, Orbital Sciences' Cygnus did so in 2014.[51]

The Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program was initiated in 2010 with the purpose of creating commercially operated manned spacecraft capable of delivering at least four crew members to the ISS, staying docked for 180 days and then returning them back to Earth.[52] These spacecraft, like the SpaceX Dragon V2 and Sierra Nevada Corporation's Dream Chaser are expected to become operational around the end of 2018.[53]

Although the Constellation program was canceled, it has been replaced with a very similar beyond low Earth orbit program. The Orion spacecraft has been left virtually unchanged from its previous design. The planned Ares V rocket has been replaced with the smaller Space Launch System (SLS), which is planned to launch both Orion and other necessary hardware.[54]Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1), an unmanned test flight of the Orion spacecraft, launched on December 5, 2014 on a Delta IV Heavy rocket.[55]Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) is the unmanned initial launch of the SLS, which is planned for 2019.[55] Exploration Mission-2 (EM-2) is the first manned flight of Orion and SLS and is scheduled for 2023.[55] EM-2 is a 10-14-day mission planned to place a crew of four into Lunar orbit. As of April 2018[update], the destination for EM-3 and immediate destination focus for this new program is still in-flux.[56]

Linear aerospike engine for the cancelled X-33 |  The Dragon spacecraft, one of the Space Shuttle's several successors, is seen here on its way to deliver cargo to the ISS |  Vision for the developmental Orion spacecraft |  Ares I test |

Assets and transition plan

Atlantis about 30 minutes after final touchdown

The Space Shuttle program occupied over 654 facilities, used over 1.2 million line items of equipment, and employed over 5,000 people. The total value of equipment was over $12 billion. Shuttle-related facilities represented over a quarter of NASA's inventory. There were over 1,200 active suppliers to the program throughout the United States. NASA's transition plan had the program operating through 2010 with a transition and retirement phase lasting through 2015. During this time, the Ares I and Orion as well as the Altair Lunar Lander were to be under development,[57] although these programs have since been canceled.

in the 2010s, two major programs for human spaceflight were Commercial Crew Development and the Space Launch System with the Orion capsule.[58]Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39 was, for example, used to launch a Falcon Heavy rocket.

Critiques

The Space Shuttle program has been criticized for failing to achieve its promised cost and utility goals, as well as design, cost, management, and safety issues.[59] Others have argued that the Shuttle program was a step backwards from the Apollo Program, which, while extremely dangerous, accomplished far more scientific and space exploration endeavors than the Shuttle ever could.

After both the Challenger disaster and the Columbia disaster, high-profile boards convened to investigate the accidents with both committees returning praise and serious critiques to the program and NASA management. Some of the most famous of the criticisms, most of management, came from Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman, in his report that followed his appointment to the commission responsible for investigating the Challenger disaster.[60]

Support vehicles

Many other vehicles were used in support of the Space Shuttle program, mainly terrestrial transportation vehicles.

- The Crawler-Transporter carried the Mobile Launcher Platform and the Space Shuttle from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to Launch Complex 39, originally built for Project Apollo.

- The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) were two modified Boeing 747s. Either could fly an orbiter from alternative landing sites back to the Kennedy Space Center. These aircraft were retired to the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark at the Armstrong Flight Research Center and Space Center Houston.

- A 36-wheeled transport trailer, the Orbiter Transfer System, originally built for the U.S. Air Force's launch facility at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California (since then converted for Delta IV rockets) would transport the orbiter from the landing facility to the launch pad, which allowed both "stacking" and launch without utilizing a separate VAB-style building and crawler-transporter roadway. Prior to the closing of the Vandenberg facility, orbiters were transported from the OPF to the VAB on their undercarriages, only to be raised when the orbiter was being lifted for attachment to the SRB/ET stack. The trailer allowed the transportation of the orbiter from the OPF to either the SCA "Mate-Demate" stand or the VAB without placing any additional stress on the undercarriage.

- The Crew Transport Vehicle (CTV), a modified airport jet bridge, was used to assist astronauts to egress from the orbiter after landing. Upon entering the CTV, astronauts could take off their launch and re-entry suits then proceed to chairs and beds for medical checks before being transported back to the crew quarters in the Operations and Checkout Building. Originally built for Project Apollo.

- The Astrovan was used to transport astronauts from the crew quarters in the Operations and Checkout Building to the launch pad on launch day. It was also used to transport astronauts back again from the Crew Transport Vehicle at the Shuttle Landing Facility.

- The three locomotives serving the NASA Railroad, used to transport segments of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters, were determined to be no longer needed for day-to-day operation at the Kennedy Space Center. In April 2015, locomotive No. 1 was sent to Natchitoches Parish Port and No. 3 sent to the Madison Railroad. Locomotive No. 2 was sent to the Gold Coast Railroad Museum in 2014.[61]

Crawler-transporter No.2 ("Franz") in a December 2004 road test after track shoe replacement |  Atlantis being prepared to be mated to the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft using the Mate-Demate Device following STS-44. |  MV Freedom Star was a NASA recovery ship for the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters |

See also

|

|

|

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

^ Launius, Roger D. "Space Task Group Report, 1969"..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab "International Space Station Historical Timeline".

^ "Breaking News | Shannon to review options for deep space exploration". Spaceflight Now. August 29, 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

^ abcde Hepplewhite, T.A. The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA's Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1999.

^ Callahan, Jason (October 4, 2014). "How Richard Nixon Changed NASA".

^ General Accounting Office. Cost Benefit Analysis Used in Support of the Space Shuttle Program. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office, 1972.

^ Rebecca Onion (November 15, 2012). "I Say "Space Shuttle," You Say "Space Clipper"". Slate. The Slate Group. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

^ ab Borenstein, Seth (July 5, 2011). "AP Science Writer". Boston Globe. Associated Press. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

^ Brooks, Dawn (date unknown). The Names of the Space Shuttle Orbiters. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 26 July 2006 from "The Names of the Space Shuttle Orbiters". Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved July 26, 2006..

^ "Space Shuttle Unveiled". A+E Networks. 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

^ abcde "Columbia's White External Fuel Tanks".

^ Civilian and military circumpolar space shuttle missions were planned for Vandenberg AFB in California. The use of Vandenberg AFB for space shuttle missions was cancelled after space shuttle Challenger exploded on January 28, 1986

^ "Space Shuttle Weather Launch Commit Criteria and KSC End of Mission Weather Landing Criteria". KSC Release No. 39-99. NASA Kennedy Space Center. Archived from the original on June 26, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

^ abc Logsdon, John A. "Return to Flight...Challenger Accident".

^ https://blogs.nasa.gov/commercialcrew/2018/01/11/nasas-commercial-crew-program-target-test-flight-dates-2/

^ Administrator, NASA (March 6, 2016). "Independence Day at NASA Dryden – 30 Years Ago".

^ abcde "Spacelab joined diverse scientists and disciplines on 28 Shuttle missions". NASA. March 15, 1999. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

^ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. February 1973. p. 39.

^ NASA (2003) Columbia Accident Investigation Board Public Hearing Transcript Archived August 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

^ Comptroller General (1972). "Report to the Congress: Cost-Benefit Analylsis Used in Support of the Space Shuttle Program" (PDF). United States General Accounting Office. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

^ ab NASA (2011). "How much does it cost to launch a Space Shuttle?". NASA. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

^ David, Leonard (February 11, 2005). "Total Tally of Shuttle Fleet Costs Exceed Initial Estimates". Space.com. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

^ Berger, Brian (February 7, 2006). "NASA 2006 Budget Presented: Hubble, Nuclear Initiative Suffer". Space.com. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

^ "NASA Budget Information".

^ Pielke Jr., Roger; Radford Byerly (April 7, 2011). "Shuttle programme lifetime cost". Nature. 472 (7341): 38. Bibcode:2011Natur.472...38P. doi:10.1038/472038d. PMID 21475182.

^ Foust, Jeff (2017-11-20). "Review: The Space Shuttle Program: Technologies and Accomplishments". The Space Review.

^ "Roland Statement". NASA. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

^ Weinrich, Heinz (2013). Management: A Global, Innovative, and Entrepreneurial Perspective. p. 126.

^ Klikauer, Thomas (2016). Management Education: Fragments of an Emancipatory Theory. p. 220.

^ Keuper, Franz (2013). Finance Bundling and Finance Transformation: Shared Services Next Level. p. i.

^ Chien, Philip (June 27, 2006) "NASA wants shuttle to fly despite safety misgivings." The Washington Times

^ "Dumping NASA's New Ares I Rocket Would Cost Billions".

^ President George W. Bush (Attributed) (2004). "President Bush Offers New Vision For NASA". nasa.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2004.

^ Mark, Roy "Mandatory Shuttle Retirement Temporarily Postponed" (April 30, 2009) Green IT, e-week.com

^ "Space Shuttle Atlantis Exhibit Opens with Support from Souvenirs".

^ "Space Shuttle Endeavour homepage".

^ ab "Human Space Flight (HSF) – Space Shuttle".

^ ab (www.spacefuture.com), Peter Wainwright. "Space Future – The Future of Space Tourism".

^ abcde (www.spacefuture.com), Peter Wainwright. "Space Future – The Space Tourist".

^ [1]

^ [2]

^ ab [3]

^ ab "Politics played a big role in why NASA doesn't already have a new spacecraft to replace the retiring space shuttles. Funding and technical challenges put a stop to any attempts to build the ' Space Shuttle 2.'".

^ http://www.astronautix.com/s/shuttleii.html

^ abc "Reusable Launch Vehicle".

^ abc [4]

^ "X-38 project's cancellation irks NASA, partners".

^ x0av6 (August 4, 2016). "HL-20 – Lifting Body Spaceplane for Personnel Launch System".

^ "NASA ACRV".

^ "NASA Selects Crew and Cargo Transportation to Orbit Partners" (Press release). NASA. August 18, 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

^ Bergin, Chris (October 6, 2011). "ISS partners prepare to welcome SpaceX and Orbital in a busy 2012". NASASpaceFlight.com (Not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved December 13, 2011.

^ Berger, Brian (February 1, 2011). "Biggest CCDev Award Goes to Sierra Nevada". Imaginova Corp. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

^ "NASA Commercial Crew Program Mission in Sight for 2018". NASA. January 4, 2018. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

^ "NASA Announces Design for New Deep Space Exploration System". NASA. September 14, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

^ abc Bergin, Chris (February 23, 2012). "Acronyms to Ascent – SLS managers create development milestone roadmap". NASA. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

^ Bergin, Chris (March 26, 2012). "NASA Advisory Council: Select a Human Exploration Destination ASAP". NasaSpaceflight (not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved April 28, 2012.

^ Olson, John; Joel Kearns (August 2008). "NASA Transition Management Plan" (PDF). JICB-001. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

^ [5]

^ A Rocket to Nowhere, Maciej Cegłowski, Idle Words, March 8, 2005.

^ http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/51-l/docs/rogers-commission/Appendix-F.txt

^ "NASA Railroad rides into sunset". Florida Today.

Further reading

- Shuttle Reference manual

- Orbiter Vehicles

- Shuttle Program Funding 1992 – 2002

- NASA Space Shuttle News Reference – 1981 (PDF document)

- R. A. Pielke, "Space Shuttle Value open to Interpretation", Aviation Week, issue 26. July 1993, p. 57 (.pdf)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Space Shuttle program. |

- Official NASA Mission Site

- NASA Johnson Space Center Space Shuttle Site

- Official Space Shuttle Mission Archives

NASA Space Shuttle Multimedia Gallery & Archives

Shuttle audio, video, and images – searchable archives from STS-67 (1995) to present

Kennedy Space Center Media Gallery – searchable video/audio/photo gallery

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the Space Shuttle

- U.S. Space Flight History: Space Shuttle Program

- Weather criteria for Shuttle launch

- Consolidated Launch Manifest: Space Shuttle Flights and ISS Assembly Sequence

- USENET posting – Unofficial Space FAQ by Jon Leech