Arctic Ocean

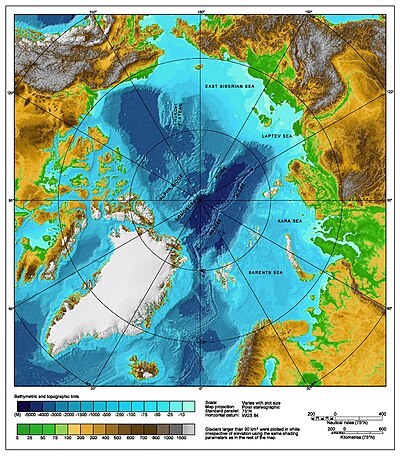

Map of the Arctic Ocean, with borders as delineated by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), including Hudson Bay (some of which is south of 57°N latitude, off the map).

|

| Earth's oceans |

|---|

|

World Ocean |

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans.[1] The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, although some oceanographers call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea or simply the Arctic Sea, classifying it a mediterranean sea or an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean.[2][3] It is also seen as the northernmost part of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

Located mostly in the Arctic north polar region in the middle of the Northern Hemisphere, the Arctic Ocean is almost completely surrounded by Eurasia and North America. It is partly covered by sea ice throughout the year and almost completely in winter. The Arctic Ocean's surface temperature and salinity vary seasonally as the ice cover melts and freezes;[4] its salinity is the lowest on average of the five major oceans, due to low evaporation, heavy fresh water inflow from rivers and streams, and limited connection and outflow to surrounding oceanic waters with higher salinities. The summer shrinking of the ice has been quoted at 50%.[1] The US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) uses satellite data to provide a daily record of Arctic sea ice cover and the rate of melting compared to an average period and specific past years.

Contents

1 History

2 Geography

2.1 Extent and major ports

2.1.1 United States

2.1.2 Canada

2.1.3 Greenland

2.1.4 Norway

2.1.5 Russia

2.2 Arctic shelves

2.3 Underwater features

3 Oceanography

3.1 Water flow

3.2 Sea ice

4 Climate

5 Animal and plant life

6 Natural resources

7 Environmental concerns

7.1 Arctic ice melting

7.2 Clathrate breakdown

7.3 Other concerns

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

History

Human habitation in the North American polar region goes back at least 50,000–17,000 years ago, during the Wisconsin glaciation. At this time, falling sea levels allowed people to move across the Bering land bridge that joined Siberia to north west North America (Alaska), leading to the Settlement of the Americas.[5]

Thule archaeological site

Paleo-Eskimo groups included the Pre-Dorset (c. 3200 – 850 B.C.); the Saqqaq culture of Greenland (2500 – 800 B.C.); the Independence I and Independence II cultures of northeastern Canada and Greenland (c. 2400 – 1800 B.C. and c. 800 – 1 B.C.); the Groswater of Labrador and Nunavik, and the Dorset culture (500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.), which spread across Arctic North America. The Dorset were the last major Paleo-Eskimo culture in the Arctic before the migration east from present-day Alaska of the Thule, the ancestors of the modern Inuit.[6]

The Thule Tradition lasted from about 200 B.C. to 1600 A.D. around the Bering Strait, the Thule people being the prehistoric ancestors of the Inuit who now live in Northern Labrador.[7]

For much of European history, the north polar regions remained largely unexplored and their geography conjectural. Pytheas of Massilia recorded an account of a journey northward in 325 BC, to a land he called "Eschate Thule", where the Sun only set for three hours each day and the water was replaced by a congealed substance "on which one can neither walk nor sail". He was probably describing loose sea ice known today as "growlers" or "bergy bits"; his "Thule" was probably Norway, though the Faroe Islands or Shetland have also been suggested.[8]

Emanuel Bowen's 1780s map of the Arctic features a "Northern Ocean".

Early cartographers were unsure whether to draw the region around the North Pole as land (as in Johannes Ruysch's map of 1507, or Gerardus Mercator's map of 1595) or water (as with Martin Waldseemüller's world map of 1507). The fervent desire of European merchants for a northern passage, the Northern Sea Route or the Northwest Passage, to "Cathay" (China) caused water to win out, and by 1723 mapmakers such as Johann Homann featured an extensive "Oceanus Septentrionalis" at the northern edge of their charts.

The few expeditions to penetrate much beyond the Arctic Circle in this era added only small islands, such as Novaya Zemlya (11th century) and Spitzbergen (1596), though since these were often surrounded by pack-ice, their northern limits were not so clear. The makers of navigational charts, more conservative than some of the more fanciful cartographers, tended to leave the region blank, with only fragments of known coastline sketched in.

This lack of knowledge of what lay north of the shifting barrier of ice gave rise to a number of conjectures. In England and other European nations, the myth of an "Open Polar Sea" was persistent. John Barrow, longtime Second Secretary of the British Admiralty, promoted exploration of the region from 1818 to 1845 in search of this.

In the United States in the 1850s and 1860s, the explorers Elisha Kane and Isaac Israel Hayes both claimed to have seen part of this elusive body of water. Even quite late in the century, the eminent authority Matthew Fontaine Maury included a description of the Open Polar Sea in his textbook The Physical Geography of the Sea (1883). Nevertheless, as all the explorers who travelled closer and closer to the pole reported, the polar ice cap is quite thick, and persists year-round.

Fridtjof Nansen was the first to make a nautical crossing of the Arctic Ocean, in 1896. The first surface crossing of the ocean was led by Wally Herbert in 1969, in a dog sled expedition from Alaska to Svalbard, with air support.[9] The first nautical transit of the north pole was made in 1958 by the submarine USS Nautilus, and the first surface nautical transit occurred in 1977 by the icebreaker NS Arktika.

Since 1937, Soviet and Russian manned drifting ice stations have extensively monitored the Arctic Ocean. Scientific settlements were established on the drift ice and carried thousands of kilometers by ice floes.[10]

In World War II, the European region of the Arctic Ocean was heavily contested: the Allied commitment to resupply the Soviet Union via its northern ports was opposed by German naval and air forces.

Since 1954 commercial airlines have flown over the Arctic Ocean (see Polar route).

Geography

A bathymetric/topographic map of the Arctic Ocean and the surrounding lands.

The Arctic region; of note, the region's southerly border on this map is depicted by a red isotherm, with all territory to the north having an average temperature of less than 10 °C (50 °F) in July.

The Arctic Ocean occupies a roughly circular basin and covers an area of about 14,056,000 km2 (5,427,000 sq mi), almost the size of Antarctica.[11][12] The coastline is 45,390 km (28,200 mi) long.[11][13] It is surrounded by the land masses of Eurasia, North America, Greenland, and by several islands.

It is generally taken to include Baffin Bay, Barents Sea, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, East Siberian Sea, Greenland Sea, Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Kara Sea, Laptev Sea, White Sea and other tributary bodies of water. It is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Bering Strait and to the Atlantic Ocean through the Greenland Sea and Labrador Sea.[1]

Countries bordering the Arctic Ocean are: Russia, Norway, Iceland, Greenland, Canada and the United States.

Extent and major ports

There are several ports and harbors around the Arctic Ocean[14]

United States

In Alaska, the main ports are Barrow (71°17′44″N 156°45′59″W / 71.29556°N 156.76639°W / 71.29556; -156.76639 (Barrow)) and Prudhoe Bay (70°19′32″N 148°42′41″W / 70.32556°N 148.71139°W / 70.32556; -148.71139 (Prudhoe)).

Canada

In Canada, ships may anchor at Churchill (Port of Churchill) (58°46′28″N 094°11′37″W / 58.77444°N 94.19361°W / 58.77444; -94.19361 (Port of Churchill)) in Manitoba, Nanisivik (Nanisivik Naval Facility) (73°04′08″N 084°32′57″W / 73.06889°N 84.54917°W / 73.06889; -84.54917 (Nanisivik Naval Facility)) in Nunavut,[15]Tuktoyaktuk (69°26′34″N 133°01′52″W / 69.44278°N 133.03111°W / 69.44278; -133.03111 (Tuktoyaktuk)) or Inuvik (68°21′42″N 133°43′50″W / 68.36167°N 133.73056°W / 68.36167; -133.73056 (Inuvik)) in the Northwest Territories.

Greenland

In Greenland, the main port is at Nuuk (Nuuk Port and Harbour) (64°10′15″N 051°43′15″W / 64.17083°N 51.72083°W / 64.17083; -51.72083 (Nuuk Port and Harbour)).

Norway

In Norway, Kirkenes (69°43′37″N 030°02′44″E / 69.72694°N 30.04556°E / 69.72694; 30.04556 (Kirkenes)) and Vardø (70°22′14″N 031°06′27″E / 70.37056°N 31.10750°E / 70.37056; 31.10750 (Vardø)) are ports on the mainland. Also, there is Longyearbyen (78°13′12″N 15°39′00″E / 78.22000°N 15.65000°E / 78.22000; 15.65000 (Longyearbyen)) on Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago, next to Fram Strait.

Russia

In Russia, major ports sorted by the different sea areas are:

Murmansk (68°58′N 033°05′E / 68.967°N 33.083°E / 68.967; 33.083 (Murmansk)) in the Barents Sea

Arkhangelsk (64°32′N 040°32′E / 64.533°N 40.533°E / 64.533; 40.533 (Arkhangelsk)) in the White Sea

Labytnangi (66°39′26″N 066°25′06″E / 66.65722°N 66.41833°E / 66.65722; 66.41833 (Labytnangi)) Salekhard (66°32′N 066°36′E / 66.533°N 66.600°E / 66.533; 66.600 (Salekhard)), Dudinka (69°24′N 086°11′E / 69.400°N 86.183°E / 69.400; 86.183 (Dudinka)), Igarka (67°28′N 86°35′E / 67.467°N 86.583°E / 67.467; 86.583 (Igarka)) and Dikson (73°30′N 080°31′E / 73.500°N 80.517°E / 73.500; 80.517 (Dikson)) in the Kara Sea

Tiksi (71°38′N 128°52′E / 71.633°N 128.867°E / 71.633; 128.867 (Tiksi)) in the Laptev Sea

Pevek (69°42′N 170°17′E / 69.700°N 170.283°E / 69.700; 170.283 (Pevek)) in the East Siberian Sea

Arctic shelves

The ocean's Arctic shelf comprises a number of continental shelves, including the Canadian Arctic shelf, underlying the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, and the Russian continental shelf, which is sometimes simply called the "Arctic Shelf" because it is greater in extent. The Russian continental shelf consists of three separate, smaller shelves, the Barents Shelf, Chukchi Sea Shelf and Siberian Shelf. Of these three, the Siberian Shelf is the largest such shelf in the world. The Siberian Shelf holds large oil and gas reserves, and the Chukchi shelf forms the border between Russian and the United States as stated in the USSR–USA Maritime Boundary Agreement. The whole area is subject to international territorial claims.

Underwater features

An underwater ridge, the Lomonosov Ridge, divides the deep sea North Polar Basin into two oceanic basins: the Eurasian Basin, which is between 4,000 and 4,500 m (13,100 and 14,800 ft) deep, and the Amerasian Basin (sometimes called the North American, or Hyperborean Basin), which is about 4,000 m (13,000 ft) deep. The bathymetry of the ocean bottom is marked by fault block ridges, abyssal plains, ocean deeps, and basins. The average depth of the Arctic Ocean is 1,038 m (3,406 ft).[16] The deepest point is Litke Deep in the Eurasian Basin, at 5,450 m (17,880 ft).

The two major basins are further subdivided by ridges into the Canada Basin (between Alaska/Canada and the Alpha Ridge), Makarov Basin (between the Alpha and Lomonosov Ridges), Amundsen Basin (between Lomonosov and Gakkel ridges), and Nansen Basin (between the Gakkel Ridge and the continental shelf that includes the Franz Josef Land).

Oceanography

Water flow

Density structure of the upper 1,200 m (3,900 ft) in the Arctic Ocean. Profiles of temperature and salinity for the Amundsen Basin, the Canadian Basin and the Greenland Sea are sketched in this cartoon.

In large parts of the Arctic Ocean, the top layer (about 50 m (160 ft)) is of lower salinity and lower temperature than the rest. It remains relatively stable, because the salinity effect on density is bigger than the temperature effect. It is fed by the freshwater input of the big Siberian and Canadian streams (Ob, Yenisei, Lena, Mackenzie), the water of which quasi floats on the saltier, denser, deeper ocean water. Between this lower salinity layer and the bulk of the ocean lies the so-called halocline, in which both salinity and temperature are rising with increasing depth.

A copepod

Because of its relative isolation from other oceans, the Arctic Ocean has a uniquely complex system of water flow. It is classified as a mediterranean sea, which as “a part of the world ocean which has only limited communication with the major ocean basins (these being the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans) and where the circulation is dominated by thermohaline forcing”.[17] The Arctic Ocean has a total volume of 18.07×106 km3, equal to about 1.3% of the World Ocean. Mean surface circulation is predominately cyclonic on the Eurasian side and anticyclonic in the Canadian Basin.[18]

Water enters from both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and can be divided into three unique water masses. The deepest water mass is called Arctic Bottom Water and begins around 900 metres (3,000 feet) depth.[17] It is composed of the densest water in the World Ocean and has two main sources: Arctic shelf water and Greenland Sea Deep Water. Water in the shelf region that begins as inflow from the Pacific passes through the narrow Bering Strait at an average rate of 0.8 Sverdrups and reaches the Chukchi Sea.[19] During the winter, cold Alaskan winds blow over the Chukchi Sea, freezing the surface water and pushing this newly formed ice out to the Pacific. The speed of the ice drift is roughly 1–4 cm/s.[18] This process leaves dense, salty waters in the sea that sink over the continental shelf into the western Arctic Ocean and create a halocline.[20]

The Kennedy Channel.

This water is met by Greenland Sea Deep Water, which forms during the passage of winter storms. As temperatures cool dramatically in the winter, ice forms and intense vertical convection allows the water to become dense enough to sink below the warm saline water below.[17] Arctic Bottom Water is critically important because of its outflow, which contributes to the formation of Atlantic Deep Water. The overturning of this water plays a key role in global circulation and the moderation of climate.

In the depth range of 150–900 metres (490–2,950 feet) is a water mass referred to as Atlantic Water. Inflow from the North Atlantic Current enters through the Fram Strait, cooling and sinking to form the deepest layer of the halocline, where it circles the Arctic Basin counter-clockwise. This is the highest volumetric inflow to the Arctic Ocean, equalling about 10 times that of the Pacific inflow, and it creates the Arctic Ocean Boundary Current.[19] It flows slowly, at about 0.02 m/s.[17] Atlantic Water has the same salinity as Arctic Bottom Water but is much warmer (up to 3 °C). In fact, this water mass is actually warmer than the surface water, and remains submerged only due to the role of salinity in density.[17] When water reaches the basin it is pushed by strong winds into a large circular current called the Beaufort Gyre. Water in the Beaufort Gyre is far less saline than that of the Chukchi Sea due to inflow from large Canadian and Siberian rivers.[20]

The final defined water mass in the Arctic Ocean is called Arctic Surface Water and is found from 150–200 metres (490–660 feet). The most important feature of this water mass is a section referred to as the sub-surface layer. It is a product of Atlantic water that enters through canyons and is subjected to intense mixing on the Siberian Shelf.[17] As it is entrained, it cools and acts a heat shield for the surface layer. This insulation keeps the warm Atlantic Water from melting the surface ice. Additionally, this water forms the swiftest currents of the Arctic, with speed of around 0.3–0.6 m/s.[17] Complementing the water from the canyons, some Pacific water that does not sink to the shelf region after passing through the Bering Strait also contributes to this water mass.

Waters originating in the Pacific and Atlantic both exit through the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard Island, which is about 2,700 metres (8,900 feet) deep and 350 kilometres (220 miles) wide. This outflow is about 9 Sv.[19] The width of the Fram Strait is what allows for both inflow and outflow on the Atlantic side of the Arctic Ocean. Because of this, it is influenced by the Coriolis force, which concentrates outflow to the East Greenland Current on the western side and inflow to the Norwegian Current on the eastern side.[17] Pacific water also exits along the west coast of Greenland and the Hudson Strait (1–2 Sv), providing nutrients to the Canadian Archipelago.[19]

As noted, the process of ice formation and movement is a key driver in Arctic Ocean circulation and the formation of water masses. With this dependence, the Arctic Ocean experiences variations due to seasonal changes in sea ice cover. Sea ice movement is the result of wind forcing, which is related to a number of meteorological conditions that the Arctic experiences throughout the year. For example, the Beaufort High—an extension of the Siberian High system—is a pressure system that drives the anticyclonic motion of the Beaufort Gyre.[18] During the summer, this area of high pressure is pushed out closer to its Siberian and Canadian sides. In addition, there is a sea level pressure (SLP) ridge over Greenland that drives strong northerly winds through the Fram Strait, facilitating ice export. In the summer, the SLP contrast is smaller, producing weaker winds. A final example of seasonal pressure system movement is the low pressure system that exists over the Nordic and Barents Seas. It is an extension of the Icelandic Low, which creates cyclonic ocean circulation in this area. The low shifts to center over the North Pole in the summer. These variations in the Arctic all contribute to ice drift reaching its weakest point during the summer months. There is also evidence that the drift is associated with the phase of the Arctic Oscillation and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.[18]

Sea ice

Sea cover in the Arctic Ocean, showing the median, 2005 and 2007 coverage [21]

Much of the Arctic Ocean is covered by sea ice that varies in extent and thickness seasonally. The mean extent of the ice has been decreasing since 1980 from the average winter value of 15,600,000 km2 (6,023,200 sq mi) at a rate of 3% per decade. The seasonal variations are about 7,000,000 km2 (2,702,700 sq mi) with the maximum in April and minimum in September. The sea ice is affected by wind and ocean currents, which can move and rotate very large areas of ice. Zones of compression also arise, where the ice piles up to form pack ice.[22][23][24]

Icebergs occasionally break away from northern Ellesmere Island, and icebergs are formed from glaciers in western Greenland and extreme northeastern Canada. Icebergs are not sea ice but may becoming embedded in the pack ice. Icebergs pose a hazard to ships, of which the Titanic is one of the most famous. The ocean is virtually icelocked from October to June, and the superstructure of ships are subject to icing from October to May.[14] Before the advent of modern icebreakers, ships sailing the Arctic Ocean risked being trapped or crushed by sea ice (although the Baychimo drifted through the Arctic Ocean untended for decades despite these hazards).

Climate

Play media

Play mediaChanges in ice between 1990–1999

Under the influence of the Quaternary glaciation, the Arctic Ocean is contained in a polar climate characterized by persistent cold and relatively narrow annual temperature ranges. Winters are characterized by the polar night, extreme cold, frequent low-level temperature inversions, and stable weather conditions.[25]Cyclones are only common on the Atlantic side.[26] Summers are characterized by continuous daylight (midnight sun), and temperatures can rise above the melting point (0 °C (32 °F). Cyclones are more frequent in summer and may bring rain or snow.[26] It is cloudy year-round, with mean cloud cover ranging from 60% in winter to over 80% in summer.[27]

The temperature of the surface of the Arctic Ocean is fairly constant, near the freezing point of seawater. Because the Arctic Ocean consists of saltwater, the temperature must reach −1.8 °C (28.8 °F) before freezing occurs.

The density of sea water, in contrast to fresh water, increases as it nears the freezing point and thus it tends to sink. It is generally necessary that the upper 100–150 m (330–490 ft) of ocean water cools to the freezing point for sea ice to form.[28] In the winter the relatively warm ocean water exerts a moderating influence, even when covered by ice. This is one reason why the Arctic does not experience the extreme temperatures seen on the Antarctic continent.

There is considerable seasonal variation in how much pack ice of the Arctic ice pack covers the Arctic Ocean. Much of the Arctic ice pack is also covered in snow for about 10 months of the year. The maximum snow cover is in March or April — about 20 to 50 cm (7.9 to 19.7 in) over the frozen ocean.

The climate of the Arctic region has varied significantly in the past. As recently as 55 million years ago, during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, the region reached an average annual temperature of 10–20 °C (50–68 °F).[29] The surface waters of the northernmost[30] Arctic Ocean warmed, seasonally at least, enough to support tropical lifeforms (the dinoflagellates Apectodinium augustum) requiring surface temperatures of over 22 °C (72 °F).[31]

Animal and plant life

Three polar bears approach USS Honolulu near the North Pole.

Endangered marine species in the Arctic Ocean include walruses and whales. The area has a fragile ecosystem which is slow to change and slow to recover from disruptions or damage.[14]Lion's mane jellyfish are abundant in the waters of the Arctic, and the banded gunnel is the only species of gunnel that lives in the ocean.

The Arctic Ocean has relatively little plant life except for phytoplankton.[32] Phytoplankton are a crucial part of the ocean and there are massive amounts of them in the Arctic, where they feed on nutrients from rivers and the currents of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.[33] During summer, the sun is out day and night, thus enabling the phytoplankton to photosynthesize for long periods of time and reproduce quickly. However, the reverse is true in winter when they struggle to get enough light to survive.[33]

Natural resources

Petroleum and natural gas fields, placer deposits, polymetallic nodules, sand and gravel aggregates, fish, seals and whales can all be found in abundance in the region.[14][24]

The political dead zone near the center of the sea is also the focus of a mounting dispute between the United States, Russia, Canada, Norway, and Denmark.[34] It is significant for the global energy market because it may hold 25% or more of the world's undiscovered oil and gas resources.[35]

Environmental concerns

Arctic ice melting

The Arctic ice pack is thinning, and in many years there is also a seasonal hole in the ozone layer.[36]

Reduction of the area of Arctic sea ice reduces the planet's average albedo, possibly resulting in global warming in a positive feedback mechanism.[24][37] Research shows that the Arctic may become ice free for the first time in human history within a few years or by 2040.[38][39] Estimates vary for when the last time the Arctic was ice free: 65 million years ago when fossils indicate that plants existed there to as few as 5,500 years ago; ice and ocean cores going back 8000 years to the last warm period or 125,000 during the last intraglacial period.[40]

Warming temperatures in the Arctic may cause large amounts of fresh meltwater to enter the north Atlantic, possibly disrupting global ocean current patterns. Potentially severe changes in the Earth's climate might then ensue.[37]

As the extent of sea ice diminishes and sea level rises, the effect of storms such as the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 on open water increases, as does possible salt-water damage to vegetation on shore at locations such as the Mackenzie's river delta as stronger storm surges become more likely.[41]