Lydia

| Lydia (Λυδία) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient region of Anatolia | |

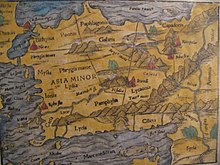

Map of the Lydian Empire in its final period of sovereignty under Croesus, c. 547 BC. The border in the 7th century BC is in red. | |

| Location | Western Anatolia, Salihli, Manisa, Turkey |

| State existed | 1200–546 BC |

| Language | Lydian |

| Historical capitals | Sardis |

| Notable rulers | Gyges, Croesus |

| Persian satrapy | Lydia |

| Roman province | Asia, Lydia |

Lydian Empire circa 600 BC.

Lydia (Assyrian: Luddu; Greek: Λυδία, Lydía; Turkish: Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish provinces of Uşak, Manisa and inland İzmir. Its population spoke an Anatolian language known as Lydian. Its capital was Sardis.[1]

The Kingdom of Lydia existed from about 1200 BC to 546 BC. At its greatest extent, during the 7th century BC, it covered all of western Anatolia. In 546 BC, it became a province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, known as the satrapy of Lydia or Sparda in Old Persian. In 133 BC, it became part of the Roman province of Asia.

Coins are said to have been invented in Lydia around the 7th century BC.[2]

Contents

1 Defining Lydia

2 Geography

3 Language

4 History

4.1 Early history: Maeonia and Lydia

4.2 In Greek mythology

4.3 First coinage

4.4 Autochthonous dynasties

4.5 Persian Empire

4.6 Hellenistic Empire

4.7 Roman province of Asia

4.8 Roman province of Lydia

4.9 Byzantine (and Crusader) age

4.10 Under Turkish rule

5 Christianity

5.1 Episcopal sees

6 Lydian gods

7 See also

8 References

9 Sources

10 Further reading

11 External links

Defining Lydia

The endonym Śfard (the name the Lydians called themselves) survives in bilingual and trilingual stone-carved notices of the Achaemenid Empire: the satrapy of Sparda (Old Persian), Aramaic Saparda, Babylonian Sapardu, Elamitic Išbarda, Hebrew .mw-parser-output .script-hebrew,.mw-parser-output .script-Hebrfont-size:1.15em;font-family:"Ezra SIL","Ezra SIL SR","Keter Aram Tsova","Taamey Ashkenaz","Taamey David CLM","Taamey Frank CLM","Frank Ruehl CLM","Keter YG","Shofar","David CLM","Hadasim CLM","Simple CLM","Nachlieli","SBL BibLit","SBL Hebrew",Cardo,Alef,"Noto Serif Hebrew","Noto Sans Hebrew","David Libre",David,"Times New Roman",Gisha,Arial,FreeSerif,FreeSansסְפָרַד.[3] These in the Greek tradition are associated with Sardis, the capital city of King Gyges, constructed during the 7th century BC.

The region of the Lydian kingdom was during the 15th-14th centuries part of the Arzawa kingdom. However, the Lydian language is not usually categorized as part of the Luwic subgroup, as are the other nearby Anatolian languages Luwian, Carian, and Lycian.[4]

Portrait of Croesus, last King of Lydia, Attic red-figure amphora, painted ca. 500–490 BC.

An Etruscan/Lydian association has long been a subject of conjecture. The Greek historian Herodotus stated that the Etruscans came from Lydia, repeated in Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid, and Etruscan-like language was found on the Lemnos stele from the Aegean Sea island of Lemnos. However, the decipherment of Lydian and its classification as an Anatolian language mean that Etruscan and Lydian were not even part of the same language family. Furthermore, a mitochondrial DNA study (2013) suggests that the Etruscans were probably an indigenous population, showing that Etruscans appear to fall very close to a Neolithic population from Central Europe and to other Tuscan populations, strongly suggesting that the Etruscan civilization developed locally from the Villanovan culture, and genetic links between Tuscany and Anatolia date back to at least 5,000 years ago during the Neolithic.[5]

Geography

The boundaries of historical Lydia varied across the centuries. It was bounded first by Mysia, Caria, Phrygia and coastal Ionia. Later, the military power of Alyattes and Croesus expanded Lydia, which, with its capital at Sardis, controlled all Asia Minor west of the River Halys, except Lycia. After the Persian conquest the River Maeander was regarded as its southern boundary, and during imperial Roman times Lydia comprised the country between Mysia and Caria on the one side and Phrygia and the Aegean Sea on the other.

Language

The Lydian language was an Indo-European language in the Anatolian language family, related to Luwian and Hittite. Due to its fragmentary attestation, the meanings of many words are unknown but much of the grammar has been determined. Similar to other Anatolian languages, it featured extensive use of prefixes and grammatical particles to chain clauses together.[6] Lydian had also undergone extensive syncope, leading to numerous consonant clusters atypical of Indo-European languages. Lydian finally became extinct during the 1st century BC.

History

Early history: Maeonia and Lydia

Bin Tepe royal funeral tumulus (tomb of Alyattes, father of Croesus), Lydia, 6th century BC.

Tomb of Alyattes.

Lydia developed after the decline of the Hittite Empire in the 12th century BC. In Hittite times, the name for the region had been Arzawa. According to Greek source, the original name of the Lydian kingdom was Maionia (Μαιονία), or Maeonia: Homer (Iliad ii. 865; v. 43, xi. 431) refers to the inhabitants of Lydia as Maiones (Μαίονες).[7] Homer describes their capital not as Sardis but as Hyde (Iliad xx. 385); Hyde may have been the name of the district in which Sardis was located.[8] Later, Herodotus (Histories i. 7) adds that the "Meiones" were renamed Lydians after their king Lydus (Λυδός), son of Atys, during the mythical epoch that preceded the Heracleid dynasty. This etiological eponym served to account for the Greek ethnic name Lydoi (Λυδοί). The Hebrew term for Lydians, Lûḏîm (לודים), as found in the Book of Jeremiah (46.9), has been similarly considered, beginning with Flavius Josephus, to be derived from Lud son of Shem;[9] however, Hippolytus of Rome (234 AD) offered an alternative opinion that the Lydians were descended from Ludim, son of Mizraim. During Biblical times, the Lydian warriors were famous archers. Some Maeones still existed during historical times in the upland interior along the River Hermus, where a town named Maeonia existed, according to Pliny the Elder (Natural History book v:30) and Hierocles (author of Synecdemus).

In Greek mythology

Lydian mythology is virtually unknown, and their literature and rituals have been lost due to the absence of any monuments or archaeological finds with extensive inscriptions; therefore, myths involving Lydia are mainly from Greek mythology.

For the Greeks, Tantalus was a primordial ruler of mythic Lydia, and Niobe his proud daughter; her husband Amphion associated Lydia with Thebes in Greece, and through Pelops the line of Tantalus was part of the founding myths of Mycenae's second dynasty. (In reference to the myth of Bellerophon, Karl Kerenyi remarked, in The Heroes of The Greeks 1959, p. 83. "As Lykia was thus connected with Crete, and as the person of Pelops, the hero of Olympia, connected Lydia with the Peloponnesos, so Bellerophontes connected another Asian country, or rather two, Lykia and Karia, with the kingdom of Argos".)

The Pactolus river, from which Lydia obtained electrum, a combination of silver and gold.

In Greek myth, Lydia had also adopted the double-axe symbol, that also appears in the Mycenaean civilization, the labrys.[10]Omphale, daughter of the river Iardanos, was a ruler of Lydia, whom Heracles was required to serve for a time. His adventures in Lydia are the adventures of a Greek hero in a peripheral and foreign land: during his stay, Heracles enslaved the Itones; killed Syleus, who forced passers-by to hoe his vineyard; slew the serpent of the river Sangarios (which appears in the heavens as the constellation Ophiucus)[11] and captured the simian tricksters, the Cercopes. Accounts tell of at least one son of Heracles who was born to either Omphale or a slave-girl: Herodotus (Histories i. 7) says this was Alcaeus who began the line of Lydian Heracleidae which ended with the death of Candaules c. 687 BC. Diodorus Siculus (4.31.8) and Ovid (Heroides 9.54) mention a son called Lamos, while pseudo-Apollodorus (Bibliotheke 2.7.8) gives the name Agelaus and Pausanias (2.21.3) names Tyrsenus as the son of Heracles by "the Lydian woman".

All three heroic ancestors indicate a Lydian dynasty claiming Heracles as their ancestor. Herodotus (1.7) refers to a Heraclid dynasty of kings who ruled Lydia, yet were perhaps not descended from Omphale. He also mentions (1.94) the recurring legend that the Etruscan civilization was founded by colonists from Lydia led by Tyrrhenus, brother of Lydus. Dionysius of Halicarnassus was skeptical of this story, indicating that the Etruscan language and customs were known to be totally dissimilar to those of the Lydians. Later chronologists ignored Herodotus' statement that Agron was the first Heraclid to be a king, and included his immediate forefathers Alcaeus, Belus and Ninus in their list of kings of Lydia. Strabo (5.2.2) has Atys, father of Lydus and Tyrrhenus, as a descendant of Heracles and Omphale but that contradicts virtually all other accounts which name Atys, Lydus and Tyrrhenus among the pre-Heraclid kings and princes of Lydia. The gold deposits in the river Pactolus that were the source of the proverbial wealth of Croesus (Lydia's last king) were said to have been left there when the legendary king Midas of Phrygia washed away the "Midas touch" in its waters.

In Euripides' tragedy The Bacchae, Dionysus, while he is maintaining his human disguise, declares his country to be Lydia.[12]

First coinage

Early 6th century BC Lydian electrum coin (one-third stater denomination)

According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to use gold and silver coins and the first to establish retail shops in permanent locations.[13] It is not known, however, whether Herodotus meant that the Lydians were the first to use coins of pure gold and pure silver or the first precious metal coins in general. Despite this ambiguity, this statement of Herodotus is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited on behalf of the argument that Lydians invented coinage, at least in the West, although the first coins (under Alyattes I, reigned c.591–c.560 BC) were neither gold nor silver but an alloy of the two called electrum.[14]

The dating of these first stamped coins is one of the most frequently debated topics of ancient numismatics,[15] with dates ranging from 700 BC to 550 BC, but the most common opinion is that they were minted at or near the beginning of the reign of King Alyattes (sometimes referred to incorrectly as Alyattes II).[16][17] The first coins were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver that occurs naturally but that was further debased by the Lydians with added silver and copper.[18]

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinnerdisplay:flex;flex-direction:column.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trowdisplay:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglemargin:1px;float:left.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theaderclear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaptiontext-align:left;background-color:transparent.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-lefttext-align:left.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-righttext-align:right.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-centertext-align:center@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trowjustify-content:center.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaptiontext-align:center

The largest of these coins are commonly referred to as a 1/3 stater (trite) denomination, weighing around 4.7 grams, though no full staters of this type have ever been found, and the 1/3 stater probably should be referred to more correctly as a stater, after a type of a transversely held scale, the weights used in such a scale (from ancient Greek ίστημι=to stand), which also means "standard."[20] These coins were stamped with a lion's head adorned with what is likely a sunburst, which was the king's symbol.[21] The most prolific mint for early electrum coins was Sardis which produced large quantities of the lion head thirds, sixths and twelfths along with lion paw fractions.[22] To complement the largest denomination, fractions were made, including a hekte (sixth), hemihekte (twelfth), and so forth down to a 96th, with the 1/96 stater weighing only about 0.15 grams. There is disagreement, however, over whether the fractions below the twelfth are actually Lydian.[23]

Alyattes' son was Croesus (Reigned c.560–c.546 BC), who became associated with great wealth. Croesus is credited with issuing the Croeseid, the first true gold coins with a standardised purity for general circulation,[19] and the world's first bimetallic monetary system circa 550 BCE.[19]

It took some time before ancient coins were used for commerce and trade. Even the smallest-denomination electrum coins, perhaps worth about a day's subsistence, would have been too valuable for buying a loaf of bread.[24] The first coins to be used for retailing on a large-scale basis were likely small silver fractions, Hemiobol, Ancient Greek coinage minted in Cyme (Aeolis) under Hermodike II then by the Ionian Greeks in the late sixth century BC.[25]

Sardis was renowned as a beautiful city. Around 550 BC, near the beginning of his reign, Croesus paid for the construction of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. Croesus was defeated in battle by Cyrus II of Persia in 546 BC, with the Lydian kingdom losing its autonomy and becoming a Persian satrapy.

Autochthonous dynasties

According to Herodotus, Lydia was ruled by three dynasties from the second millennium BC to 546 BC. The first two dynasties are legendary and the third is historical. Herodotus mentions three early Maeonian kings: Manes, his son Atys and his grandson Lydus.[26] Lydus gave his name to the country and its people. One of his descendants was Iardanus, for whom Heracles was in service at one time. Heracles had an affair with one of Iardanus' slave-girls and their son Alcaeus was the first of the Lydian Heraclids.[27]

The Maeonians relinquished control to the Heracleidae and Herodotus says they ruled through 22 generations for a total of 505 years from c. 1192 BC. The first Heraclid king was Agron, the great-grandson of Alcaeus.[27] He was succeeded by 19 Heraclid kings, names unknown, all succeeding father to son.[27] In the 8th century BC, Meles became the 21st and penultimate Heraclid king and the last was his son Candaules (died c. 687 BC), who was assassinated and succeeded by his former friend Gyges, who began the Mermnad dynasty.[28][29]

Gyges, called Gugu of Luddu in Assyrian inscriptions (c. 687 – c. 652 BC).[30][31] Once established on the throne, Gyges devoted himself to consolidating his kingdom and making it a military power. The capital was relocated from Hyde to Sardis. Barbarian Cimmerians sacked many Lydian cities, except for Sardis. Gyges was the son of Dascylus, who, when recalled from banishment in Cappadocia by the Lydian king Myrsilos—called Candaules "the Dog-strangler" (a title of the Lydian Hermes) by the Greeks—sent his son back to Lydia instead of himself. Gyges turned to Egypt, sending his faithful Carian troops along with Ionian mercenaries to assist Psammetichus in ending Assyrian domination. Some Bible scholars believe that Gyges of Lydia was the Biblical character Gog, ruler of Magog, who is mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelation.

Ardys (c. 652 BC – c. 603 BC).[32]

Lydian delegation at Apadana, circa 500 BC

Sadyattes (c. 603 – c. 591 BC). Herodotus wrote (in his Inquiries) that he fought with Cyaxares, the descendant of Deioces, and with the Medes, drove out the Cimmerians from Asia, captured Smyrna, which had been founded by colonists from Colophon, and invaded the city-states Clazomenae and Miletus.[33]

Alyattes (c. 591–560 BC). One of the greatest kings of Lydia. When Cyaxares attacked Lydia, the kings of Cilicia and Babylon intervened and negotiated a peace in 585 BC, whereby the River Halys was established as the Medes' frontier with Lydia.[34] Herodotus writes:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0On the refusal of Alyattes to give up his supplicants when Cyaxares sent to demand them of him, war broke out between the Lydians and the Medes, and continued for five years, with various success. In the course of it the Medes gained many victories over the Lydians, and the Lydians also gained many victories over the Medes.

The Battle of the Eclipse was the final battle in a five year[35] war between Alyattes of Lydia and Cyaxares of the Medes. It took place on 28 May 585 BC, and ended abruptly due to a total solar eclipse.

Croesus (560–546 BC). The expression "rich as Croesus" refers to this king. The Lydian Empire ended after Croesus attacked the Persian Empire of Cyrus II and was defeated in 546 BC.[29][36]

Persian Empire

Lydia, including Ionia, during the Achaemenid Empire.

Xerxes I tomb, Lydian soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BC

In 547 BC, the Lydian king Croesus besieged and captured the Persian city of Pteria in Cappadocia and enslaved its inhabitants. The Persian king Cyrus The Great marched with his army against the Lydians. The Battle of Pteria resulted in a stalemate, forcing the Lydians to retreat to their capital city of Sardis. Some months later the Persian and Lydian kings met at the Battle of Thymbra. Cyrus won and captured the capital city of Sardis by 546 BC.[37] Lydia became a province (satrapy) of the Persian Empire.

Hellenistic Empire

Lydia remained a satrapy after Persia's conquest by the Macedonian king Alexander III (the Great) of Macedon.

When Alexander's empire ended after his death, Lydia was possessed by the major Asian diadoch dynasty, the Seleucids, and when it was unable to maintain its territory in Asia Minor, Lydia was acquired by the Attalid dynasty of Pergamum. Its last king avoided the spoils and ravage of a Roman war of conquest by leaving the realm by testament to the Roman Empire.

Roman province of Asia

Roman province of Asia

Photo of a 15th-century map showing Lydia

When the Romans entered the capital Sardis in 133 BC, Lydia, as the other western parts of the Attalid legacy, became part of the province of Asia, a very rich Roman province, worthy of a governor with the high rank of proconsul. The whole west of Asia Minor had Jewish colonies very early, and Christianity was also soon present there. Acts of the Apostles 16:14-15 mentions the baptism of a merchant woman called "Lydia" from Thyatira, known as Lydia of Thyatira, in what had once been the satrapy of Lydia. Christianity spread rapidly during the 3rd century AD, based on the nearby Exarchate of Ephesus.

Roman province of Lydia

Under the tetrarchy reform of Emperor Diocletian in 296 AD, Lydia was revived as the name of a separate Roman province, much smaller than the former satrapy, with its capital at Sardis.

Together with the provinces of Caria, Hellespontus, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phrygia prima and Phrygia secunda, Pisidia (all in modern Turkey) and the Insulae (Ionian islands, mostly in modern Greece), it formed the diocese (under a vicarius) of Asiana, which was part of the praetorian prefecture of Oriens, together with the dioceses Pontiana (most of the rest of Asia Minor), Oriens proper (mainly Syria), Aegyptus (Egypt) and Thraciae (on the Balkans, roughly Bulgaria).

Byzantine (and Crusader) age

Under the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (610–641), Lydia became part of Anatolikon, one of the original themata, and later of Thrakesion. Although the Seljuk Turks conquered most of the rest of Anatolia, forming the Sultanate of Ikonion (Konya), Lydia remained part of the Byzantine Empire. While the Venetians occupied Constantinople and Greece as a result of the Fourth Crusade, Lydia continued as a part of the Byzantine rump state called the Nicene Empire based at Nicaea until 1261.

Under Turkish rule

Lydia was captured finally by Turkish beyliks, which were all absorbed by the Ottoman state in 1390. The area became part of the Ottoman Aidin Vilayet (province), and is now in the modern republic of Turkey.

Christianity

Lydia had numerous Christian communities and, after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, Lydia became one of the provinces of the diocese of Asia in the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The ecclesiastical province of Lydia had a metropolitan diocese at Sardis and suffragan dioceses for Philadelphia, Thyatira, Tripolis, Settae, Gordus, Tralles, Silandus, Maeonia, Apollonos Hierum, Mostene, Apollonias, Attalia, Hyrcania, Bage, Balandus, Hermocapella, Hierocaesarea, Acrassus, Dalda, Stratonicia, Cerasa, Gabala, Satala, Aureliopolis and Hellenopolis. Bishops from the various dioceses of Lydia were well represented at the Council of Nicaea in 325 and at the later ecumenical councils.[38]

Episcopal sees

Church of St John, Philadelphia (Alaşehir)

Ancient episcopal sees of the late Roman province of Lydia are listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[39]

Acrassus (in the upper valley of the Caicus)

Apollonis (Palamit)

Apollonos-Hieron (near Boldan)

Attalea in Lydia (Yanantepe)- Aureliopolis in Lydia

- Bagis

Blaundus (ruins of Süleimanli near Uşak)- Caunus

Cerasa (Eliesler)

Daldis (Narikale)- Gordus

Hermocapelia (Yahyaköy)- Hierocaesarea

- Hypaepa

Hyrcanis (Papazli)

Lipara (in the upper valley of the Caicus)

Mesotymolus (ruins near Takmak?)- Mostene (Asartepe)

- Philadelphia in Lydia

Saittae (Sidaskale)

Sala (Kepecik)- Sardes, Metropolitan Archbishopric

Satala in Lydia (Gölde in Manisa Province)- Silandus

- Stratonicea in Lydia

Tabala (Lydia) (Burgazkale)- Thyatira

Tracula (Darkale)

Tralles (ruins near Göne)- Tripolis in Lydia

Lydian gods

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Annat

- Anax

Artimus (Artemis, Diana)- Asterios

- Atergätus

- Attis

Baki. See also Bacchus- Bassareus

- Damasēn

- Gugaie/Guge/Gugaia

- Hermos

- Hipta

- Hullos

- Kandaulēs

- Kaustros

- Kubebe

- Lamētrus

- Lukos

- Lydian Lion

- Mēles

Moxus (Mopsus)- Omfalē

Pldans (Apollo)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maps of Lydia. |

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

- List of Kings of Lydia

- List of satraps of Lydia

- Ludim

- Digda

References

^ Rhodes, P.J. A History of the Classical Greek World 478-323 BC. 2nd edition. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, p. 6.

^ "Lydia" in Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press, 2010. Oxford Reference Online. 14 October 2011.

^ Tavernier, J. (2007). Iranica in the Achaemenid period (ca. 530–330 B.C.): Lexicon of Old Iranian Proper Names and Loanwords, attested in Non-Iranian Texts. Peeters. p. 91. ISBN 90-429-1833-0..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ I. Yakubovich, Sociolinguistics of the Luvian Language, Leiden: Brill, 2010, p. 6

^ Silvia Ghirotto; Francesca Tassi; Erica Fumagalli; Vincenza Colonna; Anna Sandionigi; Martina Lari; Stefania Vai; Emmanuele Petiti; Giorgio Corti; Ermanno Rizzi; Gianluca De Bellis; David Caramelli; Guido Barbujani (6 February 2013). "Origins and Evolution of the Etruscans' mtDNA". PLOS ONE. 8: e55519. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055519. PMC 3566088. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

^ "Lydia - All About Turkey". www.allaboutturkey.com.

^ As for the etymologies of Lydia and Maionia, see H. Craig Melchert "Greek mólybdos as a Loanword from Lydian", University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, pp. 3, 4, 11 (fn. 5).

^ See Strabo xiii.626.

^ Calmet, Augustin (1832). Dictionary of the Holy Bible. Crocker and Brewster. p. 648.

^ Sources noted in Karl Kerenyi, The Heroes of the Greeks 1959, p. 192.

^ Hyginus, Astronomica ii.14.

^ Euripides. The Complete Greek Tragedies Vol IV., Ed by Grene and Lattimore, line 463

^ Herodotus. Histories, I, 94.

^ Carradice and Price, Coinage in the Greek World, Seaby, London, 1988, p. 24.

^ N. Cahill and J. Kroll, "New Archaic Coin Finds at Sardis," American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 109, No. 4 (October 2005), p. 613.

^ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/croesus

^ A. Ramage, "Golden Sardis," King Croesus' Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining, edited by A. Ramage and P. Craddock, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2000, p. 18.

^ M. Cowell and K. Hyne, "Scientific Examination of the Lydian Precious Metal Coinages," King Croesus' Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2000, pp. 169-174.

^ abc Metcalf, William E. (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Oxford University Press. p. 49-50. ISBN 9780199372188.

^ L. Breglia, "Il materiale proveniente dalla base centrale dell'Artemession di Efeso e le monete di Lidia", Istituto Italiano di Numismatica Annali, volumes 18-19 (1971/72), pp. 9-25.

^ E. Robinson, "The Coins from the Ephesian Artemision Reconsidered," Journal of Hellenic Studies 71 (1951), p. 159.

^ http://www.achemenet.com/pdf/in-press/KONUK_Asia_Minor.pdf

^ M. Mitchiner, Ancient Trade and Early Coinage, Hawkins Publications, London, 2004, p. 219.

^ "Hoards, Small Change, and the Origin of Coinage," Journal of the Hellenistic Studies 84 (1964), p. 89

^ M. Mitchiner, p. 214

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 80

^ abc Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 43

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, pp. 43–46

^ ab Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 82

^ Bury & Meiggs 1975, pp. 82–83

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 45

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 46

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 46–47

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 43–48

^ Herodotus I.74

^ Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 43–79

^ New Testament Cities in Western Asia Minor: Light from Archaeology on Cities of Paul and the Seven Churches of Revelation

ISBN 1-59244-230-7 p. 65

^ Le Quien, Oriens Christianus, i. 859–98

^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013

ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819-1013

Sources

Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1975) [first published 1900]. A History of Greece (Fourth Edition). London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-15492-4.

Herodotus (1975) [first published 1954]. Burn, A. R.; de Sélincourt, Aubrey, eds. The Histories. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051260-8.

Further reading

- Reid Goldsborough. "World's First Coin".

- R. S. P. Beekes. The Origin of the Etruscans.

External links

- Livius.org: Lydia