Tengrism

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Turkish. (January 2017) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (July 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Tengrism |

|---|

|

A Central Asian religious belief and mythology. |

Related movements |

|

People |

|

Deities |

|

Scriptures |

|

Places |

|

Priests |

|

Related conceptions |

|

Also historically and geographically covered Siberia and parts of East Asia. |

Tengrism, also known as Tengriism, Tenggerism, or Tengrianism, is a Central Asian religion characterized by shamanism, animism, totemism, poly-, and monotheism,[1][2][3] and ancestor worship. It was the prevailing religion of the Turks, Mongols, Hungarians, Xiongnu and possibly Huns,[4] and the religion of the several medieval states: Göktürk Khaganate, Western Turkic Khaganate, Old Great Bulgaria, Danube Bulgaria, Volga Bulgaria and Eastern Tourkia (Khazaria). In Irk Bitig, Tengri is mentioned as Türük Tängrisi (God of Turks).[5]

Tengrism has been advocated in intellectual circles of the Turkic nations of Central Asia (including Tatarstan, Buryatia, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan) since the dissolution of the Soviet Union during the 1990s.[6] Still practiced, it is undergoing an organized revival in Sakha, Khakassia, Tuva and other Turkic nations in Siberia. Burkhanism, a movement similar to Tengrism, is concentrated in Altay.

Khukh tengri means "blue sky" in Mongolian, Mongolians still pray to Munkh Khukh Tengri ("Eternal Blue Sky") and Mongolia is sometimes poetically called the "Land of Eternal Blue Sky" (Munkh Khukh Tengriin Oron) by its inhabitants. In modern Turkey, Tengrism is known as the Göktanrı dini ("Sky God religion");[7] the Turkish "Gök" (sky) and "Tanrı" (God) correspond to the Mongolian khukh (blue) and Tengri (sky), respectively. According to Hungarian archaeological research, the religion of the Hungarians until the end of the 10th century (before Christianity) was Tengrism.[8]

Contents

1 Relationship with shamanism

2 Background

3 Symbols

4 Tengri

5 Three-world cosmology

5.1 Subterranean world (underworld)

5.2 Heavenly world

5.3 View of the world

6 Three souls of human

6.1 Soul types

6.2 Soul names

7 Central Asia

8 Temdeg Symbol and Tengriism

8.1 Temdeg Writing

9 Arghun's letters

10 Muslim opposition

11 Terms for 'shaman' and 'shamaness' in Siberian languages

12 Nestorianism and Tengrism

13 Buddhism and Tengrism

14 Tengrism in the Secret History of the Mongols

15 See also

16 Notes

17 References

Relationship with shamanism

The word "Tengrism" is a fairly new term. It is conventionally used to describe a form of Tengri-centered shamanism that prevailed on the Eurasian steppes mostly among early Turkic and Mongol Khanates. Tengrism differs from Siberian shamanism in that the polities practicing it were not small bands of hunter gatherers like the Paleosiberians but a continuous succession of pastoral, semi-sedentarized Khanates and empires from the Xiongnu Empire (founded 209 BC) till the Mongol Empire (13th century). Among Turkic peoples it was radically supplanted by Islam while in Mongolia it survives as a synthesis with Tibetan Buddhism while surviving in purer forms around Lake Khovsgol and Lake Baikal. Unlike Siberian shamanism which has no written tradition, Tengrism can be identified from Turkic and Mongolic historical texts like the Orkhon inscriptions, Secret History of the Mongols and Altan Tobchi. However, these texts are more historically oriented and are not strictly religious texts like the scriptures and sutras of sedentary civilizations which have elaborate doctrines and religious stories. On a scale of complexity Tengrism lies somewhere between the Proto-Indo-European religion (a pre-state form of pastoral shamanism on the western steppe) and its later form the Vedic religion. The eastern steppe where Tengrism developed had more centralized, hierarchical polities than the western steppe. Tengrism has been noted as more centralized, less polytheistic, less myth-intensive and more historically focused than the paganism that grew out of the western Proto-Indo-European religion. Nonetheless, the chief god Tengri (Heaven) is considered strikingly similar to the Indo-European sky god *Dyeus and the structure of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion is closer to that of the early Turks than to the religion of any people of Near Eastern or Mediterranean antiquity.[9]

Background

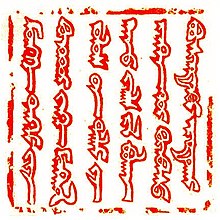

Seal from Güyüg Khan's letter to Pope Innocent IV, 1246. The first four words, from top to bottom, left to right, read "möngke ṭngri-yin küčündür" – "Under the power of the eternal heaven". The words "Tngri" (Tengri) and "zrlg" (zarlig) exhibit vowel-less archaism.

Tengri in Old Turkic script (written from right to left as t²ṅr²i)[10]

Kurşun dökme in Turkey

Tengrists view their existence as sustained by the eternal blue sky (Tengri), the fertile mother-earth spirit (Eje) and a ruler regarded as the holy spirit of the sky. Heaven, earth, spirits of nature and ancestors provide for every need and protect all humans. By living an upright, respectful life, a human will keep his world in balance and perfect his personal Wind Horse, or spirit. The Huns of the northern Caucasus reportedly believed in two gods: Tangri Han (or Tengri Khan), considered identical to the Persian Aspandiat and for whom horses were sacrificed, and Kuar (whose victims are struck by lightning).[11] Tengrism is practised in Sakha, Buryatia, Tuva and Mongolia in parallel with Tibetan Buddhism and Burkhanism.[12]

Kyrgyz means "we are forty" in the Kyrgyz language, and Kyrgyzstan's flag has 40 uniformly-spaced rays. Tengrist Khazars aided Heraclius by reportedly sending 40,000 soldiers during a joint Byzantine-Göktürk operation against the Persians.

Several Kyrgyz politicians are advocating Tengrism to fill a perceived ideological void. Dastan Sarygulov, secretary of state and former chair of the Kyrgyz state gold-mining company, established the Tengir Ordo (Army of Tengri): a civic group promoting the values and traditions of Tengrism.[13] Sarygulov also heads a Tengrist society in Bishkek claiming nearly 500,000 followers and an international scientific center of Tengrist studies.

Articles on Tengrism have been published in social-scientific journals in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev and former Kyrgyz president Askar Akayev have called Tengrism the national, "natural" religion of the Turkic peoples.[citation needed]

Symbols

Gun Ana - the sun (featured in most flags)

Umay – Goddess of fertility and virginity

Bai-Ulgan – Greatest deity, after Tengri

Erkliğ – God of space

Erlik – God of death- Flag of Sakha Republic

- Flag of Kazakhstan

- Flag of Chuvashia

Göktürk coins- Tree of Life

- Öksökö

Tengri

Buryat shaman performing a libation.

Tengrism was brought to Eastern Europe by the Bulgars.[14] It lost importance when the Uighuric kagans proclaimed Manichaeism the state religion in the eighth century.[15]

Tengrism also played a large role in the religion of the Gok-Turk and Mongol Empires. Gok-Turk translates as "celestial Turk". Genghis Khan and several generations of his followers were Tengrian believers until his fifth-generation descendant, Uzbeg Khan, turned to Islam in the 14th century.

A traditional Kyrgyz yurt in 1860 in the Syr Darya Oblast. Note the lack of a compression ring at the top.

The original Mongol khans, followers of Tengri, were known for their tolerance of other religions.[16]Möngke Khan, the fourth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, said: "We believe that there is only one God, by whom we live and by whom we die, and for whom we have an upright heart. But as God gives us the different fingers of the hand, so he gives to men diverse ways to approach him." ("Account of the Mongols. Diary of William Rubruck", religious debate in court documented by William of Rubruck on May 31, 1254).

Three-world cosmology

As in most ancient beliefs, there is a "celestial world" and an "underground world" in Tengrism. The only connection between these realms is the "Tree of Worlds" that is in the center of the worlds.

The celestial and the subterranean world are divided into seven layers (the underworld sometimes nine layers and the celestial world 17 layers). Shamans can recognize entries to travel into these realms. In the multiples of these realms, there are beings, living just like humans on the earth. They also have their own respected souls and shamans and nature spirits. Sometimes these beings visit the earth, but are invisible to people. They manifest themselves only in a strange sizzling fire or a bark to the shaman.[17][18]

Subterranean world (underworld)

There are many similarities between the earth and the underworld and its inhabitants resemble humans, but have only two souls instead of three. They lack the "Ami soul", that produces body temperature and allows breathing. Therefore, they are pale and their blood is dark. The sun and the moon of the underworld give far less light than the sun and the moon of the earth. There are also forests, rivers and settlements underground.[19]

Erlik Khan (Mongolian: Erleg Khan) one of the sons of Tengri, is the ruler of the underworld. He controls the souls here, some of them waiting to be reborn again. If a sick human is not dead yet, a shaman can move to the underworld to negotiate with Erlik to bring the person back to life. If he fails, the person dies.[20]

Heavenly world

The celestial world has many similarities with the earth,as if there would be no humams. There is a healthy, untouched nature here, and the natives of this place have never deviated from the traditions of their ancestors. This world is much righter than the earth and is under the auspices of Ulgen another son of Tengri. Shamans can also visit this world.[21]

On some days, the doors of this heavenly world are opened and the light shines through the clouds. During this moment, the prayers of the shamans are most influential. A shaman performs his imaginary journey, which takes him to the heavens, by ridig a black bird, a deer or a horse or by going into the shape into these animals. Otherwise he may scale the World-Tree or pass the rainbow to reach the heavenly world.[22]

View of the world

According to the adherence of Tengrism, the world is not only a three-dimensional environment, but also a rotating circle. Everything is bound by this circle and the tire is always renewed without stopping. The three dimensions of the Earth consists of the movement of the sun, the season which are constantly moving, and the souls of all creatures that are born again after death.

Three souls of human

It is believed that people and animals have many souls. Generally, each person is considered to have three souls, but the names, characteristics an numbers of the souls may be different among some of the tribes: For example, for Samoyets, a Mongol tribe living in the north of Siberia, believe that women consist of four and men of five souls. Since animals also have souls, humans must respect animals.

Soul types

According Paulsen and Jultkratz, who conducted research in North America, North Asia and Central Asia by Paulsen and Jultkratz, explained two souls of this belief are the same to all people:

Nefes (Breath or Nafs, life or bodily spirit)- Shadow soul / Free soul

Soul names

There are many different names for human souls among the Turks and the Mongols, but their features and meanings have not been adequately researched yet.

- Among Turks: Özüt, Süne, Kut, Sür, Salkin, Tin, Körmös, Yula

- Among Mongols: Sünesün, Amin, Kut, Sülde[23]

In addition to these spirits, Jean Paul Roux draws attention to the "Özkonuk" spirit mentioned in the writings from the Buddhist periods of the Uighurs.

Julie Stewart, who devoted her life to research in Mongolia described the belief in the soul in one of her articles:

Amin ruhu: Provides breathing and body temperature. It is the soul which invigorates. (The Turkish counterpart is probably Özüt)

Sünesün ruhu: Outside of the body, this soul moves through water. It is also the part of soul, which reincarnates. After a human died, this part of the soul moves to the world-tree. When it is reborn, it comes out of a source and enters the new-born. (Also called Süne ruhu among Turks)

Sülde ruhu: It is the soul of the self that gives a person a personality. If the other souls leave the body, they only loss consciousness, but if this soul leaves the body, the human dies. This soul resides in nature after death and is not reborn.[24]

Central Asia

A revival of Tengrism has played a role in Central Asian Turkic nationalism since the 1990s. It developed in Tatarstan, where the Tengrist periodical Bizneng-Yul appeared in 1997. The movement spread during the 2000s to Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan and, to a lesser extent, Buryatia and Mongolia.[citation needed]

Temdeg Symbol and Tengriism

Mongolian shamanism "Temdeg" symbol

Temdeg Writing

- ᠲ᠋ᠠ᠊ᠮᠳ᠋ᠠ᠊ᠢ᠊ᠡ᠋

- (тэмдэг)

The term "shamanism" was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighbouring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some Western anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense. The term was used to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another.

The earliest known depiction of a Siberian shaman, drawn by the Dutch explorer Nicolaes Witsen, who wrote an account of his travels among Samoyedic- and Tungusic-speaking peoples in 1692. Witsen labeled the illustration as a "Priest of the Devil," giving this figure clawed feet to express what he thought were demonic qualities.[25]

Russian postcard based on a photo taken in 1908 by S.I. Borisov, showing a female shaman, of probable Khakas ethnicity.[26]

Since the 1990s, Russian-language literature uses Тенгрианство ("Tengrism" or "Tengrinity") in the general sense of Mongolian shamanism. Buryat scholar Irina S. Urbanaeva developed a theory of Tengrianist esoteric traditions in Central Asia after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the revival of national sentiment in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia.[27]

Although Tengrism has few active adherents, its revival of a national religion reached a larger audience in intellectual circles. Presenting Islam as foreign to the Turkic peoples, adherents are found primarily among the nationalistic parties of Central Asia. Tengrism may be interpreted as a Turkic version of Russian neopaganism. A related phenomenon is the revival of Zoroastrianism in Tajikistan.[citation needed]

By 2006, a Tengrist society in Bishkek, an "international scientific centre of Tengrist studies" and a civic group (Tengir Ordo, the "army of Tengri") were established by Kyrgyz businessman and politician Dastan Sarygulov. His ideology incorporated ethnocentrism and Pan-Turkism, but did not receive strong support. After the Kyrgyzstani presidential elections of 2005, Sarygulov became state secretary and set up a workgroup dealing with ideological issues.[28]

Another Kyrgyz proponent of Tengrism, Kubanychbek Tezekbaev, was prosecuted for inciting religious and ethnic hatred in 2011 with statements in an interview describing Kyrgyz mullahs as "former alcoholics and murderers".[29]

Arghun's letters

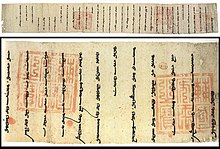

Arghun Khan's 1289 letter to Philip the Fair, in classical Mongolian script. The letter was given to the French king by Buscarel of Gisolfe.

Arghun expressed the association of Tengri with imperial legitimacy and military success. The majesty (suu) of the khan is a divine stamp granted by Tengri to a chosen individual through which Tengri controls the world order (the presence of Tengri in the khan). In this letter, "Tengri" or "Mongke Tengri" ("Eternal Heaven") is at the top of the sentence. In the middle of the magnified section, the phrase Tengri-yin Kuchin ("Power of Tengri") forms a pause before it is followed by the phrase Khagan-u Suu ("Majesty of the Khan"):

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Under the Power of the Eternal Tengri. Under the Majesty of the Khan (Kublai Khan). Arghun Our word. To the Ired Farans (King of France). Last year you sent your ambassadors led by Mar Bar Sawma telling Us: "if the soldiers of the Il-Khan ride in the direction of Misir (Egypt) we ourselves will ride from here and join you", which words We have approved and said (in reply) "praying to Tengri (Heaven) We will ride on the last month of winter on the year of the tiger and descend on Dimisq (Damascus) on the 15th of the first month of spring." Now, if, being true to your words, you send your soldiers at the appointed time and, worshipping Tengri, we conquer those citizens (of Damascus together), We will give you Orislim (Jerusalem). How can it be appropriate if you were to start amassing your soldiers later than the appointed time and appointment? What would be the use of regretting afterwards? Also, if, adding any additional messages, you let your ambassadors fly (to Us) on wings, sending Us luxuries, falcons, whatever precious articles and beasts there are from the land of the Franks, the Power of Tengri (Tengri-yin Kuchin) and the Majesty of the Khan (Khagan-u Suu) only knows how We will treat you favorably. With these words We have sent Muskeril (Buscarello) the Khorchi. Our writing was written while We were at Khondlon on the sixth khuuchid (6th day of the old moon) of the first month of summer on the year of the cow.[30]

1290 letter from Arghun to Pope Nicholas IV

Arghun expressed Tengrism's non-dogmatic side. The name Mongke Tengri ("Eternal Tengri") is at the top of the sentence in this letter to Pope Nicholas IV, in accordance with Mongolian Tengriist writing rules). The words "Tngri" (Tengri) and "zrlg" (zarlig, decree/order) are still written with vowel-less archaism:

... Your saying "May [the Ilkhan] receive silam (baptism)" is legitimate. We say: "We the descendants of Genghis Khan, keeping our own proper Mongol identity, whether some receive silam or some don't, that is only for Eternal Tengri (Heaven) to know (decide)." People who have received silam and who, like you, have a truly honest heart and are pure, do not act against the religion and orders of the Eternal Tengri and of Misiqa (Messiah or Christ). Regarding the other peoples, those who, forgetting the Eternal Tengri and disobeying him, are lying and stealing, are there not many of them? Now, you say that we have not received silam, you are offended and harbor thoughts of discontent. [But] if one prays to Eternal Tengri and carries righteous thoughts, it is as much as if he had received silam. We have written our letter in the year of the tiger, the fifth of the new moon of the first summer month (May 14th, 1290), when we were in Urumi.[31]

Muslim opposition

Turkic worship of Tengri was mocked by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote: "The infidels - may God destroy them!"[32][33] According to Kashgari, Muhammad assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn; fires shot sparks at the Yabāqu from gates on a green mountain[34] (the Yabaqu were a Turkic people).[35]

Terms for 'shaman' and 'shamaness' in Siberian languages

- 'shaman': saman (Nedigal, Nanay, Ulcha, Orok), sama (Manchu). The variant /šaman/ (i.e., pronounced "shaman") is Evenk (whence it was borrowed into Russian).

- 'shaman': alman, olman, wolmen[36] (Yukagir)

- 'shaman': [qam] (Tatar, Shor, Oyrat), [xam] (Tuva, Tofalar)

- The Buryat word for shaman is бөө (böö) [bøː], from early Mongolian böge.[37]

- 'shaman': ńajt (Khanty, Mansi), from Proto-Uralic *nojta (c.f. Sámi noaidi)

- 'shamaness': [iduɣan] (Mongol), [udaɣan] (Yakut), udagan (Buryat), udugan (Evenki, Lamut), odogan (Nedigal). Related forms found in various Siberian languages include utagan, ubakan, utygan, utügun, iduan, or duana. All these are related to the Mongolian name of Etügen, the hearth goddess, and Etügen Eke 'Mother Earth'. Maria Czaplicka points out that Siberian languages use words for male shamans from diverse roots, but the words for female shaman are almost all from the same root. She connects this with the theory that women's practice of shamanism was established earlier than men's, that "shamans were originally female."[38]

Nestorianism and Tengrism

Tengrism has been called Nestorianism by Christian sources.[39] Turkish Nestorian manuscripts with the same rune-like characters as Old Turkic script have been found in the oasis of Turfan and the fortress of Miran.[40][41][42] It is unknown when and by whom the Bible was first translated into Turkish.[43] Most records in pre-Islamic Central Asia are written in the Old Turkic language.[44] Nestorian Christianity had followers among the Uighurs. In the Nestorian sites of Turfan, a fresco depicting Palm Sunday has been discovered.[45]

Buddhism and Tengrism

The 17th century Mongolian chronicle Altan Tobchi (Golden Summary) contains references to Tengri. Tengrism was assimilated into Mongolian Buddhism while surviving in purer forms only in far-northern Mongolia. Tengrist formulas and ceremonies were subsumed into the state religion. This is similar to the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto in Japan. The Altan Tobchi contains the following prayer at its very end:

|

|

Tengrism in the Secret History of the Mongols

Mount Burkhan Khaldun is a place where Genghis Khan regularly prayed to Tengri.

Tengri is mentioned many times in the Secret History of the Mongols written in 1240. The book starts by listing the ancestors of Genghis Khan starting from Borte Chino (Blue Wolf) born with "destiny from Tengri". Bodonchar Munkhag the 9th generation ancestor of Genghis Khan is called a "son of Tengri". When Temujin was brought to the Qongirat tribe at 9 years old to choose a wife, Dei Setsen of the Qongirat tells Yesugei the father of Temujin (Genghis Khan) that he dreamt of a white falcon, grasping the sun and the moon, come and sit on his hands. He identifies the sun and the moon with Yesugei and Temujin. Temujin then encounters Tengri in the mountains at the age of 12. The Taichiud had come for him when he was living with his siblings and mother in the wilderness, subsisting on roots, wild fruits, sparrows and fish. He was hiding in the thick forest of Terguun Heights. After three days hiding he decided to leave and was leading his horse on foot when he looked back and noticed his saddle had fallen. Temujin says "I can understand the belly strap can come loose, but how can the breast strap also come loose? Is Tengri persuading me?" He waited three more nights and decided to go out again but a tent-sized rock had blocked the way out. Again he said "Is Tengri persuading me?", returned and waited three more nights. Finally he lost patience after 9 days of hunger and went around the rock, cutting down the wood on the other side with his arrow-whittling knife, but as he came out the Taichiud were waiting for him there and promptly captured him. Toghrul later credits the defeat of the Merkits with Jamukha and Temujin to the "mercy of mighty Tengri" (paragraph 113). Khorchi of the Baarin tells Temujin of a vision given by "Zaarin Tengri" where a bull raises dust and asks for one of his horns back after charging the ger cart of Jamukha (Temujin's rival) while another ox harnessed itself to a big ger cart on the main road and followed Temujin, bellowing "Heaven and Earth have agreed to make Temujin the Lord of the nation and I am now carrying the nation to you". Temujin afterward tells his earliest companions Boorchi and Zelme that they will be appointed to the highest posts because they first followed him when he was "mercifully looked upon by Tengri" (paragraph 125). In the Battle of Khuiten, Buyuruk Khan and Quduga try using zad stones to cause a thunderstorm against Temujin but it backfires and they get stuck in slippery mud. They say "the wrath of Tengri is upon us" and flee in disorder (paragraph 143). Temujin prays to "father Tengri" on a high hill with his belt around his neck after defeating the Taichiud at Tsait Tsagaan Tal and taking 100 horses and 50 breastplates. He says "I haven't become Lord thanks to my own bravery, but I have defeated my enemies thanks to the love of my father mighty Tengri". When Nilqa Sengum the son of Toghrul Khan tries to convince him to attack Temujin, Toghrul says "How can I think evil of my son Temujin? If we think evil of him when he is such a critical support to us, Tengri will not be pleased with us". After Nilqa Sengum throws a number of tantrums Toghrul finally relents and says "I was afraid of Tengri and said how can I harm my son. If you are really capable, then you decide what you need to do".[46]

When Boorchi and Ogedei return wounded from the battle against Toghrul, Genghis Khan strikes his chest in anguish and says "May Eternal Tengri decide" (paragraph 172). Genghis Khan tells Altan and Khuchar "All of you refused to become Khan, that is why I led you as Khan. If you would have become Khan I would have charged first in battle and brought you the best women and horses if high Khukh Tengri showed us favor and defeated our enemies". After defeating the Keraits Genghis Khan says "By the blessing of Eternal Tengri I have brought low the Kerait nation and ascended the high throne" (paragraph 187). Genghis sends Subutai with an iron cart to pursue the sons of Togtoa and tells him "If you act exposed though hidden, near though far and maintain loyalty then Supreme Tengri will bless you and support you" (paragraph 199). Jamukha tells Temujin "I had no trustworthy friends, no talented brothers and my wife was a talker with great words. That is why I have lost to you Temujin, blessed and destined by Father Tengri." Genghis Khan appoints Shikhikhutug chief judge of the Empire in 1206 and tells him "Be my eyes to see and ears to hear when I am ordering the empire through the blessing of Eternal Tengri" (paragraph 203). Genghis Khan appoints Muqali "Gui Wang" because he "transmitted the word of Tengri when I was sitting under the spreading tree in the valley of Khorkhunag Jubur where Hotula Khan used to dance" (paragraph 206). He gives Khorchi of the Baarin 30 wives because he promised Khorchi he would fulfill his request for 30 wives "if what you say comes true through the mercy and power of Tengri" (paragraph 207). Genghis mentions both Eternal Tengri and "heaven and earth" when he says "By the mercy of Eternal Tengri and the blessing of heaven and earth I have greatly increased in power, united all the great nation and brought them under my reins" (paragraph 224). Genghis orders Dorbei the Fierce of the Dorbet tribe to "strictly govern your soldiers, pray to Eternal Tengri and try to conquer the Khori Tumed people" (paragraph 240). After being insulted by Asha Khambu of the Tanguts of being a weak Khan Genghis Khan says "If Eternal Tengri blesses me and I firmly pull my golden reins, then things will become clear at that time" (paragraph 256). When Asha Khambu of the Tangut insults him again after his return from the Khwarezmian campaign Genghis Khan says "How can we go back (to Mongolia) when he says such proud words? Though I die I won't let these words slip. Eternal Tengri, you decide" (paragraph 265). After Genghis Khan "ascends to Tengri" (paragraph 268) during his successful campaign against the Tangut (Xi Xia) the wheels of the returning funeral cart gets stuck in the ground and Gilugdei Baatar of the Sunud says "My horse-mounted divine lord born with destiny from Khukh Tengri, have you abandoned your great nation?" Batu Khan sends a secret letter to Ogedei Khan saying "Under the power of the Eternal Tengri, under the Majesty of my uncle the Khan, we set up a great tent to feast after we had broken the city of Meged, conquered the Orosuud (Russians), brought in eleven nations from all directions and pulled on our golden reins to hold one last meeting before going our separate directions" (paragraph 275).[47]

See also

- Heaven worship

- Manzan Gurme Toodei

- Hungarian neopaganism

- Religion in China

Notes

^ The spelling Tengrism is found in the 1960s, e.g. Bergounioux (ed.), Primitive and prehistoric religions, Volume 140, Hawthorn Books, 1966, p. 80. Tengrianism is a reflection of the Russian term, Тенгрианство. It is reported in 1996 ("so-called Tengrianism") in Shnirelʹman (ed.), Who gets the past?: competition for ancestors among non-Russian intellectuals in Russia, Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1996, .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 978-0-8018-5221-3, p. 31 in the context of the nationalist rivalry over Bulgar legacy. The spellings Tengriism and Tengrianity are later, reported (deprecatingly, in scare quotes) in 2004 in Central Asiatic journal, vol. 48–49 (2004), p. 238. The Turkish term Tengricilik is also found from the 1990s. Mongolian Тэнгэр шүтлэг is used in a 1999 biography of Genghis Khan (Boldbaatar et. al, Чингис хаан, 1162-1227, Хаадын сан, 1999, p. 18).

^ R. Meserve, Religions in the central Asian environment. In: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV, The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century, Part Two: The achievements, p. 68:- "[...] The ‘imperial’ religion was more monotheistic, centred around the all-powerful god Tengri, the sky god."

^ Michael Fergus, Janar Jandosova, Kazakhstan: Coming of Age, Stacey International, 2003, p.91:- "[...] a profound combination of monotheism and polytheism that has come to be known as Tengrism."

^ "There is no doubt that between the 6th and 9th centuries Tengrism was the religion among the nomads of the steppes" Yazar András Róna-Tas, Hungarians and Europe in the early Middle Ages: an introduction to early Hungarian history, Yayıncı Central European University Press, 1999,

ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1, p. 151.

^ Jean-Paul Roux, Die alttürkische Mythologie, p. 255

^ Saunders, Robert A. and Vlad Strukov (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 412–13. ISBN 978-0-81085475-8.

^ Mehmet Eröz (2010-03-10). Eski Türk dini (gök tanrı inancı) ve Alevîlik-Bektaşilik. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

^ Fodor István, A magyarok ősi vallásáról (About the old religion of the Hungarians) Vallástudományi Tanulmányok. 6/2004, Budapest, p. 17–19

^ Mircea Eliade, John C. Holt, Patterns in comparative religion, 1958, p. 94.

^ Tekin, Talat (1993). Irk bitig (the book of omens). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-447-03426-5.

^ Hungarians & Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early... - András Róna-Tas. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

^ Balkanlar'dan Uluğ Türkistan'a Türk halk inançları Cilt 1, Yaşar Kalafat, Berikan, 2007

^ McDermott, Roger. "The Jamestown Foundation: High-Ranking Kyrgyz Official Proposes New National Ideology". Jamestown.org. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

^ Bulgars and the Slavs followed ancestral religious practices and worshipped the sky-god Tengri. Bulgaria, Patriarchal Orthodox Church of --, p. 79, at Google Books

^ Buddhist studies review, Volumes 6-8, 1989, p. 164.

^ Osman Turan, The Ideal of World Domination among the Medieval Turks, in Studia Islamica, No. 4 (1955), pp. 77-90

^ http://members.tripod.com/Mongolian_Page/shaman.txt

^ Türk Mitolojisi, Murat Uraz, 1992

ISBN 9759792359 Parameter error in ISBN: Invalid ISBN.

^ http://members.tripod.com/Mongolian_Page/shaman.txt

^ http://members.tripod.com/Mongolian_Page/shaman.txt

^ http://members.tripod.com/Mongolian_Page/shaman.txt

^ http://members.tripod.com/Mongolian_Page/shaman.txt

^ Götter und Mythen in Zentralasien und Nordeurasien Käthe Uray-Kőhalmi, Jean-Paul Roux, Pertev N. Boratav, Edith Vertes:

ISBN 3-12-909870-4 İçinden: Jean-Paul Roux: Die alttürkische Mythologie (Eski Türk mitolojisi)

^ Julie Stewart - Mongolian Shamanism (İng.)

^ Hutton 2001. p. 32.

^ Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-05-8295-7. pp. 77, 287; Znamensky, Andrei A. (2005). "Az ősiség szépsége: altáji török sámánok a szibériai regionális gondolkodásban (1860–1920)". In Molnár, Ádám. Csodaszarvas. Őstörténet, vallás és néphagyomány. Vol. I (in Hungarian). Budapest: Molnár Kiadó. pp. 117–134. ISBN 978-963-218-200-1., p. 128

^ Irina S. Urbanaeva (Урбанаева И.С.),

Шаманизм монгольского мира как выражение тенгрианской эзотерической традиции Центральной Азии ("Shamanism in the Mongolian World as an Expression of the Tengrianist Esoteric Traditions of Central Asia"), Центрально-азиатский шаманизм: философские, исторические, религиозные аспекты. Материалы международного симпозиума, 20-26 июня 1996 г., Ulan-Ude (1996); English language discussion in Andrei A. Znamenski, Shamanism in Siberia: Russian records of indigenous spirituality, Springer, 2003,

ISBN 978-1-4020-1740-7, 350–352.

^ Erica Marat, Kyrgyz Government Unable to Produce New National Ideology, 22 February 2006, CACI Analyst, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

^ RFE/RL 31 January 2012.

^ For another translation here

^ Translation on page 18 here

^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

^ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 95 (1): 68–80. doi:10.2307/599159. JSTOR 599159.

^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

^ Mehmet Fuat Köprülü; Gary Leiser; Robert Dankoff (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-415-36686-1.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2001. Retrieved 17 July 2009.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Lessing, Ferdinand D., ed. (1960). Mongolian-English Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 123.

^ Czaplicka, Maria (1914). "XII. Shamanism and Sex". Aboriginal Siberia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

^ A. S. Amanjolov, History of ancient Türkic Script, Almaty 2003, p.305

^ University of Bonn. Department of Linguistics and Cultural Studies of Central Asia, Issue 37, VGH Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH Publishing, 2008, p.107

^ Jens Wilkens, Wolfgang Voigt, Dieter George, Hartmut-Ortwin Feistel, German Oriental Society, List of Oriental Manuscripts in Germany, Volume 12, Franz Steiner Publishing, 2000, p.480

^ Volker Adam, Jens Peter Loud, Andrew White, Bibliography old Turkish Studies, Otto Harrassowitz Publishing, 2000, p.40

^ Materialia Turcica, Volumes 22-24, Brockmeyer Publishing Studies, 2001, p.127

^ "Turfan research: Scripts and languages in pre-Islamic Central Asia, Academy of Sciences of Berlin and Brandenburg, 2011" (in German). Bbaw.de. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

^ M. S. Asimov, The historical,social and economic setting, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1999, p.204

^ http://altaica.ru/SECRET/cleaves_shI.pdf

^ http://altaica.ru/SECRET/cleaves_shI.pdf

References

Brent, Peter (1976). The Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan: His Triumph and his Legacy. London: Book Club Associates.

Richtsfeld, Bruno J. (2004). "Rezente ostmongolische Schöpfungs-, Ursprungs- und Weltkatastrophenerzählungen und ihre innerasiatischen Motiv- und Sujetparallelen". Münchner Beiträge zur Völkerkunde. Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Museums für Völkerkunde München. 9. pp. 225–274.