Plantations in the American South

A cotton plantation on the Mississippi, 1884 lithograph

Plantations are an important aspect of the history of the American South, particularly the antebellum (pre-American Civil War) era. The mild subtropical climate, plentiful rainfall, and fertile soils of the southeastern United States allowed the flourishing of large plantations, where large numbers of workers, usually Africans held captive for slave labor, were required for agricultural production.

Contents

1 Personnel

1.1 Plantation owner

1.2 Overseer

1.3 Slaves

2 Plantation crops

3 Plantation architecture and landscape

4 See also

5 References

6 Further reading

6.1 Primary sources

Personnel

Plantation owner

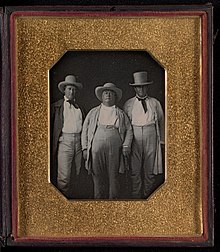

Three planters, after 1845, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Old Plantation: How We Lived in Great House and Cabin before the War by Confederate chaplain and planter James Battle Avirett

An individual who owned a plantation was known as a planter. Historians of the antebellum South have generally defined "planter" most precisely as a person owning property (real estate) and 20 or more slaves.[1] The wealthiest planters, such as the Virginia elite with plantations near the James River, owned more land and slaves than other farmers. Tobacco was the major cash crop in the Upper South (in the original Chesapeake Bay Colonies of Virginia and Maryland, and in parts of the Carolinas).

The later development of cotton and sugar cultivation in the Deep South in the early 18th century led to the establishment of large plantations which had hundreds of slaves. The great majority of Southern farmers owned no slaves or owned fewer than five slaves. Slaves were much more expensive than land.

In the "Black Belt" counties of Alabama and Mississippi, the terms "planter" and "farmer" were often synonymous;[2] a "planter" was generally a farmer who owned many slaves. While most Southerners were not slave-owners, and while the majority of slaveholders held ten or fewer slaves, planters were those who held a significant number of slaves, mostly as agricultural labor. Planters are often spoken of as belonging to the planter elite or to the planter aristocracy in the antebellum South.

The historians Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman define large planters as those owning over 50 slaves, and medium planters as those owning between 16 and 50 slaves.[3] Historian David Williams, in A People's History of the Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom, suggests that the minimum requirement for planter status was twenty negroes, especially since a southern planter could exempt Confederate duty for one white male per twenty slaves owned.[4] In his study of Black Belt counties in Alabama, Jonathan Weiner defines planters by ownership of real property, rather than of slaves. A planter, for Weiner, owned at least $10,000 worth of real estate in 1850 and $32,000 worth in 1860, equivalent to about the top 8 percent of landowners.[5] In his study of southwest Georgia, Lee Formwalt defines planters in terms of size of land holdings rather than in terms of numbers of slaves. Formwalt's planters are in the top 4.5 percent of landowners, translating into real estate worth six thousand dollars or more in 1850, 24,000 dollars or more in 1860, and eleven thousand dollars or more in 1870.[6] In his study of Harrison County, Texas, Randolph B. Campbell classifies large planters as owners of 20 slaves, and small planters as owners of between 10 and 19 slaves.[7] In Chicot and Phillips Counties, Arkansas, Carl H. Moneyhon defines large planters as owners of twenty or more slaves, and of six hundred or more acres.[8]

Many nostalgic memoirs about plantation life were published in the post-bellum South.[9] For example, James Battle Avirett, who grew up on the Avirett-Stephens Plantation in Onslow County, North Carolina and served as an Episcopal chaplain in the Confederate States Army, published The Old Plantation: How We Lived in Great House and Cabin before the War in 1901.[9] Such memoirs often included descriptions of Christmas as the epitome of anti-modern order exemplified by the "great house" and extended family.[10]

Overseer

On larger plantations an overseer represented the planter in matters of daily management. Usually portrayed as uncouth, ill-educated and low-class, he had the difficult and often despised task of middleman and the often contradictory goals of fostering both productivity and the enslaved work-force.[11]

Slaves

Plantation crops

Crops cultivated on antebellum plantations included cotton, tobacco, sugar, indigo, rice, and to a lesser extent okra, yam, sweet potato, peanuts, and watermelon. By the late 18th century, most planters in the Upper South had switched from exclusive tobacco cultivation to mixed-crop production.

In the Lowcountry of South Carolina, even before the American Revolution, planters in South Carolina typically owned hundreds of slaves. (In towns and cities, families held slaves to work as household servants.) The 19th-century development of the Deep South for cotton cultivation depended on large tracts of land with much more acreage than was typical of the Chesapeake Bay area, and for labor, planters held dozens, or sometimes hundreds, of slaves.

Plantation architecture and landscape

Antebellum architecture can be seen in many extant "plantation houses", the large residences of planters and their families. Over time in each region of the plantation south a regional architecture emerged inspired by those who settled the area. Most early plantation architecture was constructed to mitigate the hot subtropical climate and provide natural cooling.

Some of earliest plantation architecture occurred in southern Louisiana by the French. Using styles and building concepts they had learned in the Caribbean, the French created many of the grand plantation homes around New Orleans. French Creole architecture began around 1699, and lasted well into the 1800s.

In the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia, the Dogtrot style house was built with a large center breezeway running through the house to mitigate the subtropical heat. The wealthiest planters in colonial Virginia constructed their manor houses in the Georgian style, e.g. the mansion of Shirley Plantation. In the 19th century, Greek Revival architecture also became popular on some of the plantation homes of the deep south.

Common plants and trees incorporated in the landscape of Southern plantation manors included Southern live oak and Southern magnolia. Both of these large trees are native to the Southern United States and were classic symbols of the old south. Southern live oaks, classically draped in Spanish moss, were planted along long paths or walkways leading to the plantation to create a grand, imposing, and majestic theme. Plantation landscapes were very well maintained and trimmed, usually, the landscape work was managed by the planter, with assistance from slaves or workers. Planters themselves also usually maintained a small flower or vegetable garden. Cash crops were not grown in these small garden plots, but rather garden plants and vegetables for enjoyment.

See also

- Plantation economy

- Plantation era

- Plain Folk of the Old South

- American gentry

J. H. Netterville, 20th-century plantation manager- Plantation complexes in the Southeastern United States

- List of plantations in the United States

- History of the Southern United States

- Plantations of Leon County

References

^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, xiii

^ Oakes, Ruling Race, 52.

^ Fogel, Robert William; Engerman, Stanley L. (1974). Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 311437227..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ David Williams, "A People's History of the Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom", New York: The New Press, 2005.

^ Wiener, Jonathan M. (Autumn 1976). "Planter Persistence and Social Change: Alabama, 1850–1870". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 7 (2): 235–60. JSTOR 202735.

^ Formwalt, Lee W. (October 1981). "Antebellum Planter Persistence: Southwest Georgia—A Case Study". Plantation Society in the Americas. 1 (3): 410–29. ISSN 0192-5059. OCLC 571605035.

^ Campbell, Randolph B (May 1982). "Population Persistence and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century Texas: Harrison County, 1850–1880". Journal of Southern History. 48 (2): 185–204. JSTOR 2207106.

^ Moneyhon, Carl H. (1992). "The Impact of the Civil War in Arkansas: The Mississippi River Plantation Counties". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 51 (2): 105–18. JSTOR 40025847.

^ ab Anderson, David (February 2005). "Down Memory Lane: Nostalgia for the Old South in Post-Civil War Plantation Reminiscences". The Journal of Southern History. 71 (1): 105–136. JSTOR 27648653. (Registration required (help)).

^ Anderson, David J. (Fall 2014). "Nostalgia for Christmas in Postbellum Plantation Reminiscences". Southern Studies: an Interdisciplinary Journal of the South. 21 (2): 39–73.

^

Richter:, William L. (2009-08-20). "Overseers". The A to Z of the Old South. The A to Z Guide Series. 51. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press (published 2009). p. 258. ISBN 9780810870000. Retrieved 2016-11-29.On larger plantations, the planter's direct representative in day-to-day management of the crops, care of the land, livestock, farm implements, and slaves was the white overseer. It was his job to work the labor force to produce a profitable crop. He was an indispensable cog in the plantation machinery. [...] The overseer has usually been portrayed as an uncouth, uneducated character of low class whose main purpose was to harass the slaves and get in the way of the planter's progressive goals of production. More than that, the overseer had a position between master and slave in which it was hard to win. Directing slave labor was looked down upon by a large number of people, North and South. He was faced with planter demands that were at times unreasonable. He was forbidden to fraternize with the slaves. He had no chance of advancement unless he left the profession. He was bombarded with incessant complaints from masters, who did not appreciate the task he faced, and slaves, who sought to play off master and overseer against each other to avoid work and gain privileges. [...] The very nature of the job was difficult. The overseer had to care for the slaves and gain the largest crop possible. These were often contradictory goals.

Further reading

- Blassingame, John W. The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (1979)

- * Evans, Chris, "The Plantation Hoe: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Commodity, 1650–1850," William and Mary Quarterly, (2012) 69#1 pp 71–100.

Phillips, Ulrich B. American Negro Slavery; a Survey of the Supply, Employment, and Control of Negro Labor, as Determined by the Plantation Regime. (1918; reprint 1966)online at Project Gutenberg; google edition

Phillips, Ulrich B. Life and Labor in the Old South. (1929). excerpts and text search

Phillips, Ulrich B. Phillips, Ulrich B. (1905). "The Economic Cost of Slaveholding in the Cotton Belt". Political Science Quarterly. 20 (2): 257–275. doi:10.2307/2140400. JSTOR 2140400.- Thompson, Edgar Tristram. The Plantation edited by Sidney Mintz and George Baca (University of South Carolina Press; 2011) 176 pages; 1933 dissertation

- Weiner, Marli Frances. Mistresses and Slaves: Plantation Women in South Carolina, 1830-80 (1997)

- White, Deborah G. Ar'n't I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (2nd ed. 1999) excerpt and text search

Smith, Julia Floyd (2017). Slavery and plantation growth in Antebellum Florida, 1821-1860 (PDF). University of Florida Press.

Primary sources

Phillips, Ulrich B., ed. Plantation and Frontier Documents, 1649–1863; Illustrative of Industrial History in the Colonial and Antebellum South: Collected from MSS. and Other Rare Sources. 2 Volumes. (1909). online edition