Chinese Exclusion Act

| |

| Long title | An Act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese. |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Chinese Exclusion Act of 1883 |

| Enacted by | the 47th United States Congress |

| Effective | May 6, 1882 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 47-126 |

| Statutes at Large | 22 Stat. 58 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

Political cartoon: Uncle Sam kicks out the Chinaman, referring to the Chinese Exclusion Act. Image published in 19th century.

The first page of the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers. Building on the 1875 Page Act, which banned Chinese women from immigrating to the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act was the first law implemented to prevent all members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating.

The act followed the Angell Treaty of 1880, a set of revisions to the U.S.–China Burlingame Treaty of 1868 that allowed the U.S. to suspend Chinese immigration. The act was initially intended to last for 10 years, but was renewed in 1892 with the Geary Act and made permanent in 1902. It was repealed by the Magnuson Act on December 17, 1943, which allowed 105 Chinese to enter per year. Chinese immigration later increased with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which abolished direct racial barriers, and later by Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the National Origins Formula.[1]

Contents

1 Background

2 Content

3 The "Driving Out" period

3.1 Rock Springs massacre of 1885

3.2 Hells Canyon Massacre of 1887

3.2.1 Horner and Findley accounts

3.2.2 The bodies

3.2.3 The aftermath

3.2.4 Current updates

4 Issues of the Act

5 Bubonic plague in Chinatown

6 Repeal and current status

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

9.1 Primary sources

10 External links

Background

This "Official Map of Chinatown 1885" was published as part of an official report of a Special Committee established by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors "on the Condition of the Chinese Quarter".

Chinese immigrant workers building the Transcontinental Railroad

The first significant Chinese immigration to North America began with the California Gold Rush of 1848–1855 and it continued with subsequent large labor projects, such as the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. During the early stages of the gold rush, when surface gold was plentiful, the Chinese were tolerated by white people, if not well received.[2] However, as gold became harder to find and competition increased, animosity toward the Chinese and other foreigners increased. After being forcibly driven from mining by a mixture of state legislators and other miners (the Foreign Miner's Tax), the immigrant Chinese began to settle in enclaves in cities, mainly San Francisco, and took up low-wage labor, such as restaurant and laundry work.[3] With the post-Civil War economy in decline by the 1870s, anti-Chinese animosity became politicized by labor leader Denis Kearney and his Workingman's Party[4] as well as by California Governor John Bigler, both of whom blamed Chinese "coolies" for depressed wage levels. Public opinion and law in California began to demonize Chinese workers and immigrants in any role, with the later half of the 1800s seeing a series of ever more restrictive laws being placed on Chinese labor, behavior and even living conditions. While many of these legislative efforts were quickly overturned by the State Supreme Court,[5] many more anti-Chinese laws continued to be passed in both California and nationally.

In the early 1850s there was resistance to the idea of excluding Chinese migrant workers from immigration because they provided essential tax revenue which helped fill the fiscal gap of California.[6] The Chinese Emperor at the time was supportive of the exclusion, citing his concerns that Chinese immigration to America would lead to a loss of labor for China.[7] But toward the end of the decade, the financial situation improved and subsequently, attempts to legislate Chinese exclusion became successful on the state level.[6] In 1858, the California Legislature passed a law that made it illegal for any person "of the Chinese or Mongolian races" to enter the state; however, this law was struck down by an unpublished opinion of the State Supreme Court in 1862.[8]

The Chinese immigrant workers provided cheap labor and did not use any of the government infrastructure (schools, hospitals, etc.) because the Chinese migrant population was predominantly made up of healthy male adults.[6] As time passed and more and more Chinese migrants arrived in California, violence would often break out in cities such as Los Angeles. At one point, Chinese men represented nearly a quarter of all wage-earning workers in California,[9] and by 1878 Congress felt compelled to try to ban immigration from China in legislation that was later vetoed by President Rutherford B. Hayes. In 1879 however, California adopted a new Constitution, which explicitly authorized the state government to determine which individuals were allowed to reside in the state, and banned the Chinese from employment by corporations and state, county or municipal governments.[10] Although debate exists over whether or not the anti-Chinese animus in California drove the federal government (the California Thesis), or whether or not Chinese racism was simply inherent in the country at that point, by 1882, the federal government was finally convinced to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned all immigration from China for a period of 10 years.

After the act was passed, most Chinese families were faced with a dilemma: stay in the United States alone or go back to China to reunite with their families.[11] Although widespread dislike for the Chinese persisted well after the law itself was passed, of note is that some capitalists and entrepreneurs resisted their exclusion because they accepted lower wages.[12]

Content

For the first time, federal law proscribed entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities. (The earlier Page Act of 1875 had prohibited immigration of Asian forced laborers and sex workers, and the Naturalization Act of 1790 prohibited naturalization of non-white subjects.) The Act excluded Chinese laborers, meaning "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining," from entering the country for ten years under penalty of imprisonment and deportation.[13][14]

Front page of The San Francisco Call -November 20th 1901, Chinese Exclusion Convention

The Chinese Exclusion Act required the few non laborers who sought entry to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to emigrate. However, this group found it increasingly difficult to prove that they were not laborers[14] because the 1882 act defined excludables as “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” Thus very few Chinese could enter the country under the 1882 law. Diplomatic officials and other officers on business, along with their house servants, for the Chinese government were also allowed entry as long as they had the proper certification verifying their credentials.[15]

The Act also affected the Chinese who had already settled in the United States. Any Chinese who left the United States had to obtain certifications for reentry, and the Act made Chinese immigrants permanent aliens by excluding them from U.S. citizenship.[13][14] After the Act's passage, Chinese men in the U.S. had little chance of ever reuniting with their wives, or of starting families in their new abodes.[13]

Amendments made in 1884 tightened the provisions that allowed previous immigrants to leave and return, and clarified that the law applied to ethnic Chinese regardless of their country of origin. The Scott Act (1888) expanded upon the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting reentry after leaving the U.S. Constitutionality of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Scott Act was upheld by the Supreme Court in Chae Chan Ping v. United States (1889); the Supreme Court declared that "the power of exclusion of foreigners [is] an incident of sovereignty belonging to the government of the United States as a part of those sovereign powers delegated by the constitution." The Act was renewed for ten years by the 1892 Geary Act, and again with no terminal date in 1902.[14] When the act was extended in 1902, it required "each Chinese resident to register and obtain a certificate of residence. Without a certificate, he or she faced deportation."[14]

Between 1882 and 1905, about 10,000 Chinese appealed against negative immigration decisions to federal court, usually via a petition for habeas corpus.[16] In most of these cases, the courts ruled in favor of the petitioner.[16] Except in cases of bias or negligence, these petitions were barred by an act that passed Congress in 1894 and was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. vs Lem Moon Sing (1895). In U.S. vs Ju Toy (1905), the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed that the port inspectors and the Secretary of Commerce had final authority on who could be admitted. Ju Toy's petition was thus barred despite the fact that the district court found that he was an American citizen. The Supreme Court determined that refusing entry at a port does not require due process and is legally equivalent to refusing entry at a land crossing. All these developments, along with the extension of the act in 1902, triggered a boycott of U.S. goods in China between 1904 and 1906.[17] There was one 1885 case in San Francisco, however, in which Treasury Department officials in Washington overturned a decision to deny entry to two Chinese students.[18]

One of the critics of the Chinese Exclusion Act was the anti-slavery/anti-imperialist Republican Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts who described the Act as "nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination."[19] It was primarily meant to retain white superiority especially with regards to working privileges.[20]

The laws were driven largely by racial concerns; immigration of persons of other races was unlimited during this period.[21] Another reason why this Act was enacted was due to the fact that American citizens faced higher unemployment as compared to workers of Chinese descent mostly in the West Coast.[22]

On the other hand, most people and unions strongly supported the Chinese Exclusion Act, including the American Federation of Labor and Knights of Labor, a labor union, who supported it because it believed that industrialists were using Chinese workers as a wedge to keep wages low.[23] Among labor and leftist organizations, the Industrial Workers of the World were the sole exception to this pattern. The IWW openly opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act from its inception in 1905.[24]

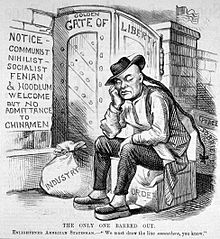

A political cartoon from 1882, showing a Chinese man being barred entry to the "Golden Gate of Liberty". The caption reads, "We must draw the line somewhere, you know."

Certificate of identity issued to Yee Wee Thing certifying that he is the son of a US citizen, issued Nov. 21, 1916. This was necessary for his immigration from China to the United States.

For all practical purposes, the Exclusion Act, along with the restrictions that followed it, froze the Chinese community in place in 1882. Limited immigration from China continued until the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. From 1910 to 1940, the Angel Island Immigration Station on what is now Angel Island State Park in San Francisco Bay served as the processing center for most of the 56,113 Chinese immigrants who are recorded as immigrating or returning from China; upwards of 30% more who showed up were returned to China. Angel Island State Park was where the Chinese immigrants were accepted to stay in the United States or made to leave.[25] Furthermore, after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which destroyed City Hall and the Hall of Records, many immigrants (known as "paper sons") claimed that they had familial ties to resident Chinese-American citizens. Whether these were true or not cannot be proven.

The Chinese Exclusion Act gave rise to the first great wave of commercial human smuggling, an activity that later spread to include other national and ethnic groups.[26]

The Chinese Exclusion Act also led to an expansion of the power of U.S. immigration law through its influence on Canada's policies on Chinese exclusion during this time because of the need for greater vigilance at the U.S.-Canada border. Shortly after the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act, Canada established the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 which imposed a head tax on Chinese migrants entering Canada. After increasing pressure from the U.S. government, Canada finally established the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 which banned most forms of immigration by the Chinese to Canada. There was also a need for this kind of border control along the U.S-Mexico border, however, efforts to control the border went along a different path because Mexico was fearful of expanding imperial power of the U.S. and did not want U.S. interference in Mexico. Not only this, but Chinese immigration to Mexico was welcomed because the Chinese immigrants filled Mexico's labor needs. The Chinese Exclusion Act actually led to heightened Chinese immigration to Mexico because of exclusion by the U.S. Therefore, the U.S. resorted to heavily policing the border along Mexico.

Later, the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration even further, excluding all classes of Chinese immigrants and extending restrictions to other Asian immigrant groups.[13] Until these restrictions were relaxed in the middle of the twentieth century, Chinese immigrants were forced to live a life separated from their families, and to build ethnic enclaves in which they could survive on their own (Chinatown).[13]

The Chinese Exclusion Act did not address the problems that whites were facing; in fact, the Chinese were quickly and eagerly replaced by the Japanese, who assumed the role of the Chinese in society. Unlike the Chinese, some Japanese were even able to climb the rungs of society by setting up businesses or becoming truck farmers.[27] However, the Japanese were later targeted in the National Origins Act of 1924, which banned immigration from east Asia entirely.

In 1891 the Government of China refused to accept the U.S. Senator Mr. Henry W. Blair as U.S. Minister to China due to his abusive remarks regarding China during negotiation of the Chinese Exclusion Act.[28]

The American Christian Rev. Dr. George F. Pentecost spoke out against western imperialism in China, saying: I personally feel convinced that it would be a good thing for America if the embargo on Chinese immigration were removed. I think that the annual admission of 100,000 into this country would be a good thing for the country. And if the same thing were done in the Philippines those islands would be a veritable Garden of Eden in twenty-five years. The presence of Chinese workmen in this country would, in my opinion, do a very great deal toward solving our labor problems. There is no comparison between the Chinaman, even of the lowest coolie class, and the man who comes here from Southeastern Europe, from Russia, or from Southern Italy. The Chinese are thoroughly good workers. That is why the laborers here hate them. I think, too, that the emigration to America would help the Chinese. At least he would come into contact with some real Christian people in America. The Chinaman lives in squalor because he is poor. If he had some prosperity his squalor would cease.[29]

The "Driving Out" period

Following the passed legislation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a period known as the "Driving Out" era was born. In this period, many anti-Chinese Americans sought out to physically force the Chinese communities to flee to other areas. Many of these outbreaks occurred in the Western states. The Rock Springs Chinese Massacre (1885) and the Hells Canyon Massacre of 1887 are two notable events in history.[30]

Rock Springs massacre of 1885

The Rock Springs massacre occurred in 1885. In 1885, many enraged white miners in Sweetwater County, Wyoming felt threatened by the Chinese and blamed them for their unemployment. As a result of the job competition, white miners expressed their frustration in physical violence where they robbed, shot, and stabbed at Chinese in Chinatown. The Chinese quickly tried to flee but in doing so, many ended up burned alive in their homes, starved to death in hidden refuge, or exposed to animal predators of the mountains. Some were successfully rescued by the passing train, but by the end of the event at least twenty-eight lives had been lost.[30]

In an attempt to appease the situation, the government intervened by sending federal troops to protect the Chinese. However, following the event, only compensations for destroyed property were paid. No-one was arrested nor held accountable for the atrocities committed during the riot.[30]

Hells Canyon Massacre of 1887

The massacre was named for the location where it took place, along the Snake River in Hells Canyon near the mouth of Deep Creek. The area contained many rocky cliffs and white rapids that together posed significant danger to human safety. Thirty-four Chinese miners were killed at the site. The miners were employed by Sam Yup company, one of the six largest Chinese companies at the time, worked in this area since October 1886. An accurate account of the event is still unclear to this day secondary to unreliable law enforcement at the time, biased news reporting, and lack of serious official investigations. However, it is speculated that the dead Chinese miners were not victims of natural causes, but rather victims of gun shot wounds during a robbery committed by a gang of seven armed horse thieves.[31]

An amount of gold worth $4,000–$5,000 was estimated to have been stolen from the miners. The whereabouts of the gold were never recovered nor further investigated. Recently, attempts to formulate an accurate picture of the event were drawn from hidden copies of trial documents that contained grand jury indictment, depositions given by the accused, notes from the trial, and historical accounts of Wallowa County by J. Harland Horner and H. Ross Findley.[31]

Horner and Findley accounts

Horner and Findley were both schoolboys at the time of the massacre but their accounts had glaring discrepancies. Findley believed the massacre was a planned event with more than just a motive to steal gold from the Chinese miners. He believed the arrested culprits wanted to eliminate the Chinese miners from the area as well, which they successfully accomplished. In contrast to most accounts, Findley only recalled 31 confirmed victims, and there was no mention of a trial. On the other hand, Horner believed that the event was a spur of the moment event and affected 34 confirmed victims. The school boys initially only had intentions to steal horses, but experienced difficulty crossing the river with the stolen horses. When the Chinese miners refused to loan their boats, the boys decided to take the boats by force.[31]

The bodies

Other disagreements on the motives could also be attributed to the fact that the bodies of the Chinese miners were only found downstream after two weeks. It is unclear if the mangled bodies found were due to human manslaughter or the aftermath of being thrown into turbulent waters. The rapids and brute force of the current could have mangled the bodies against the rocks. However, it is confirmed that the Chinese men were shot secondary to the gunshot wounds found on the bodies. Only ten bodies were identified on February 16, 1888: Chea-po, Chea-Sun, Chea-Yow, Chea-Shun, Chea Cheong, Chea Ling, Chea Chow, Chea Lin Chung, Kong Mun Kow, and Kong Ngan. Little is known about these identified men.[31]

The aftermath

Shortly following the incident, the Sam Yup company of San Francisco hired Lee Loi who later hired Joseph K. Vincent, then U.S. Commissioner, to lead an investigation. Vincent submitted his investigative report to the Chinese consulate who tried unsuccessfully to obtain justice for the Chinese miners. At around the same time, other compensation reports were also unsuccessfully filed for earlier crimes inflicted on the Chinese. In the end, on October 19, 1888, Congress agreed to greatly under-compensate for the massacre and ignore the claims for the earlier crimes. Even though the amount was greatly underpaid, it was still a small victory to the Chinese who had low expectations for relief or acknowledgement.[31]

Current updates

The US Board on Geographic Names officially named the Deep Creek massacre site to the Chinese Massacre Cove. This served as the first ever official recognition of the crime. Additionally in June 2012, a memorial was established with private funds and donations for the Chinese miners that were murdered.[31]

Issues of the Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act brought rigidity not only to the Chinese alone but to Caucasians and other races as well which lasted for about thirty years.[32] The American economy suffered a great loss as a result of this Act.[32] Some sources cite the Act as a sign of injustice and unfair treatment to the Chinese workers because the jobs they engaged in were mostly menial jobs.[33]

Bubonic plague in Chinatown

In 1900–1904 San Francisco suffered from the bubonic plague. It first struck San Francisco's Chinatown, causing people to fall ill and experience fevers, swollen lymph nodes, muscle aches and fatigue. Left untreated this infection can cause chronic complications such as gangrene,[34] meningitis, and even death.[35] The bubonic plague outbreak in San Francisco's Chinatown strengthened anti-Chinese sentiment in all of California despite scientific research at the time showing it was caused by Yersinia pestis, which was spread by fleas,[36] found in small rodents. When the first round of people died from this plague, the companies and the state denied the fact that there was an outbreak, in order to keep San Francisco's reputation and businesses in order. The plague did not derive from Chinatown; it was due to the unsanitary conditions and population density that outbreaks such as this one were spread quickly, and therefore affected a large number of people in this community.

The first deaths from the plague in San Francisco were in 1898; a French barque carried some passengers who had died of the plague. After its arrival in San Francisco, 18 more Chinatown residents died of the same symptoms. The mayor decided not to release a public warning of the outbreak, thinking it would negatively affect San Francisco's commercial business. Chinatown was quarantined, and sanitary services were suspended for some time until presence of bacteriological source was found. A sanitary campaign was launched; however many residents chose to avoid anything and everything that had to do with the plague out of fear and humiliation. As more and more deaths occurred, the city began being more aggressive, and they started checking nearly everyone in Chinatown for any signs of disease. Therefore, the Chinese community began to distrust the government even more.[37] Racism toward Chinese immigrants was socially accepted and social rights were oftentimes denied to this community. This fact made it harder for the community of Chinatown to seek medical attention for their illnesses during the plague.[38]

Repeal and current status

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed by the 1943 Magnuson Act, during a time when China had become an ally of the U.S. against Japan in World War II as that the US needed to embody an image of fairness and justice. The Magnuson Act permitted Chinese nationals already residing in the country to become naturalized citizens and stop hiding from the threat of deportation. While the Magnuson Act overturned the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act, it only allowed a national quota of 105 Chinese immigrants per year, and did not repeal the restrictions on immigration from the other Asian countries. Large scale Chinese immigration did not occur until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. The crackdown on Chinese immigrants reached a new level in its last decade, from 1956–1965, with the Chinese Confession Program launched by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, that encouraged Chinese who had committed immigration fraud to confess, so as to be eligible for some leniency in treatment.

Despite the fact that the exclusion act was repealed in 1943, the law in California prohibiting non-whites from marrying whites was not struck down until 1948, in which the California Supreme Court ruled the ban of interracial marriage within the state unconstitutional in Perez v. Sharp.[39][40] Other states had such laws until 1967, when the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Loving v. Virginia that anti-miscegenation laws across the nation are unconstitutional.

Even today, although all its constituent sections have long been repealed, Chapter 7 of Title 8 of the United States Code is headed "Exclusion of Chinese".[41] It is the only chapter of the 15 chapters in Title 8 (Aliens and Nationality) that is completely focused on a specific nationality or ethnic group. Like the following Chapter 8, "The Cooly Trade", it consists entirely of statutes that are noted as "Repealed" or "Omitted".

On June 18, 2012, the United States House of Representatives passed H.Res. 683, a resolution which had been introduced by Congresswoman Judy Chu, that formally expresses the regret of the House of Representatives for the Chinese Exclusion Act, an act which imposed almost total restrictions on Chinese immigration and naturalization and denied Chinese-Americans basic freedoms because of their ethnicity.[42]S.Res. 201, a similar resolution, had been approved by the U.S. Senate in October 2011.[43]

In 2014, the California Legislature took formal action to pass measures that formally recognize the many proud accomplishments of Chinese-Americans in California and to call upon Congress to formally apologize for the 1882 adoption of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Senate Republican Leader Bob Huff (R-Diamond Bar) and incoming Senate President pro-Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) served as Joint Authors for Senate Joint Resolution (SJR) 23[44] and Senate Concurrent Resolution (SCR) 122,[45] respectively.[46]

Both SJR 23 and SCR 122 acknowledge and celebrate the history and contributions of Chinese Americans in California. The resolutions also formally call on Congress to apologize for laws which resulted in the persecution of Chinese Americans, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act.[44][45]

Perhaps most important is the sociological implications for understanding ethnic/race relations in the context of American history: there is a tendency for minorities to be punished in times of economic, political and/or geopolitical crises. Times of social and systemic stability, however, tend to mute whatever underlying tensions exist between different groups. In times of societal crisis—whether perceived or real—patterns or retractability of American identities have erupted to the forefront of America's political landscape, often generating institutional and civil society backlash against workers from other nations, a pattern documented by Fong's research into how crises drastically alter social relationships.[47]

See also

- Anti-Chinese legislation in the United States

- Chinese Confession Program

- Chinese exclusion policy of NASA

- Chinese head tax in Canada

- Chinese massacre of 1871

- Executive Order 13769

Lau Ow Bew v. United States, which held that returning merchants did not need paperwork from China.- List of United States immigration laws

- Paper sons

- Rock Springs massacre

- Sinophobia

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, which held that the Chinese Exclusion Act could not overrule the citizenship of those born in the U.S. to Chinese parents

Yamataya v. Fisher (Japanese Immigrant Case)- Yellow Peril

References

^ Wei, William. "The Chinese-American Experience: An Introduction". HarpWeek. Archived from the original on 2014-01-26. Retrieved 2014-02-05..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Norton, Henry K. (1924). The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co. pp. 283–296. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09.

^ Pioneer Laundry Workers Assembly, K of L. Washington, D.C. "China's menace to the world : from the forum : to the public". The Library of Congress: American Memory. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

^ Kearney, Denis (28 February 1878). "Appeal from California. The Chinese Invasion. Workingmen's Address". Indianapolis Times. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

^ "1855 Cal. Stat. 194 Capitation Tax" (PDF). UC Hastings College of the Law Library Summer 2001. UC Hastings College of the Law. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

^ abc Kanazawa, Mark (September 2005). "Immigration, Exclusion, and Taxation: Anti-Chinese Legislation in Gold Rush California". The Journal of Economic History. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association. 65 (3): 779–805. doi:10.1017/s0022050705000288. JSTOR 3875017.

^ Wellborn, Mildred (1913). THE EVENTS LEADING TO THE CHINESE EXCLUSION ACTS. p. 56.

^ "Text of the Chinese Exclusion Act" (PDF). University of California, Hastings College of the Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-05. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

^ Salyer, L (1995). Law Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law. Chapell Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807845301.

^ "Constitution of the State of California, 1879" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-16.

^ Chew, Kenneth; Liu, John (March 2004). "Hidden in Plain Sight: Global Labor Force Exchange in the Chinese American Population, 1880–1940". Population and Development Review. Population Council. 30 (1): 57–78. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00003.x. JSTOR 3401498.

^ Miller, Joaquin (December 1901). "The Chinese and the Exclusion Act". The North American Review. University of Northern Iowa. 173 (541): 782–789. JSTOR 25105257.

^ abcde "Exclusion". Library of Congress. 2003-09-01. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

^ abcde "The People's Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

^ "Welcome to OurDocuments.gov". www.ourdocuments.gov.

^ ab Daniels, Roger (Spring 1999). "Book Review: Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law—Lucy E. Salyer". Archived from the original on 2012-09-25.

^ Lee, Jonathan H. X. (2015). Chinese Americans: The History and Culture of a People. ABC-CLIO. p. 26. ISBN 978-1610695497.

^ Lee, Erika (2003). At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. University of North Carolina Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0807827758.

^ Daniels, Roger (2002). Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life. Harper Perennial. p. 271. ISBN 978-0060505776.

^ "Chinese Exclusion Act". History.com. 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

^ Chin, Gabriel J. (1998). "Segregation's Last Stronghold: Race Discrimination and the Constitutional Law of Immigration". UCLA Law Review. 46 (1). SSRN 1121119.

^ "Immigration to the United States, 1789–1930". Harvard university library open collections program.

^ Kennedy, David M.; Cohen, Lizabeth; Bailey, Thomas A. (2002). The American Pageant (12th ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

^ Choi, Jennifer Jung Hee (1999). "The Rhetoric of Inclusion: The I.W.W. and Asian Workers" (PDF). Ex Post Facto: Journal of the History Students at San Francisco State University. 8: 9.

^ Dunigan, Grace (January 1, 2017). "The Chinese Exclusion Act: Why It Matters Today". Scholarly commons. 8: 5.

^ Zhang, Sheldon (2007). Smuggling and trafficking in human beings: all roads lead to America. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-275-98951-4.

^ Brinkley, Alan. American History: A Survey (12th ed.). ISBN 978-0073280479.

^ Denza, Eileen (2008). Commentary to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0199216857.

^ "America Not A Christian Nation, Says Dr. Pentecost" (PDF). The New York Times. February 11, 1912. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014.

^ abc Iris., Chang, (2004) [2003]. The Chinese in America : a narrative history. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0142004170. OCLC 55136302.

^ abcdef Nokes, R. Gregory (Fall 2006). "A Most Daring Outrage: Murders at Chinese Massacre Cove, 1887" (PDF). Oregon Historical Quarterly. 107 (3). Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

^ ab Tian, Kelly. "The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and Its Impact on North American Society". 9.

^ Bodenner, Chris (February 6, 2013). "Chinese Exclusion Act; Issues and Controversies in American History" (PDF): 5.

^ "Gangrene – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

^ "Plague – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

^ "Plague". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

^ Risse, Guenter B. (2012). Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco Chinatown. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

^ Soennichsen, John (2011-02-02). The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37947-5.

^ Chin, Gabriel; Karthikeyan, Hrishi (2002). "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910–1950". Asian Law Journal. Social Science Research Network. 9. SSRN 283998.

^ See Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711 (1948).

^ "US CODE-TITLE 8-ALIENS AND NATIONALITY". FindLaw. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

^ 112th Congress (2012) (June 8, 2012). "H.Res. 683 (112th)". Legislation. GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 9, 2012.Expressing the regret of the House of Representatives for the passage of laws that adversely affected the Chinese in the United States, including the Chinese Exclusion Act.

^ "US apologizes for Chinese Exclusion Act". China Daily, 19 June 2012

^ ab California State Assembly. "Senate Joint Resolution No. 23—Relative to Chinese Americans in California". Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California (Resolution). State of California. Ch. 134. Direct URL

^ ab California State Assembly. "Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 122—Relative to Chinese Americans in California". Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California (Resolution). State of California. Ch. 132. Direct URL

^ "Legislature Recognizes the Contributions of Chinese-Americans & Apologizes for Past Discriminatory Laws". California State Senate Republican Caucus. August 19, 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-07-26.

^ Fong, Jack (April 2008). "American Social 'Reminders' of Citizenship after September 11, 2001: Nativisms in the Ethnocratic Retractability of American Identity" (PDF). Qualitative Sociology Review. 4 (1): 69–91.

Further reading

Chan, Sucheng, ed. (1991). Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882–1943. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-0877227984.

Gold, Martin (2012). Forbidden Citizens: Chinese Exclusion and the U.S. Congress: A Legislative History. TheCapitol.Net. ISBN 978-1-58733-235-7. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

Gyory, Andrew (1998). Closing the Gate: Race, politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4739-8. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

Hsu, Madeline Y. (2015). The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691176215. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

Kil, Sang Hea (2012). "Fearing yellow, imagining white: media analysis of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882". Social Identities. 18 (6): 663–677. doi:10.1080/13504630.2012.708995.

Lee, Erika (2007). "The 'Yellow Peril' and Asian Exclusion in the Americas". Pacific Historical Review. 76 (4): 537–562. doi:10.1525/phr.2007.76.4.537. JSTOR 10.1525/phr.2007.76.4.537.

Perry, Jay (2014). "bibliography pp 242–76". The Chinese Question: California, British Columbia, and the making of transnational immigration policy, 1847–1885 (Thesis). Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

Rhodes, James Ford (1919). "VIII: The Chinese". History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850. 8: From Hayes to McKinley, 1877–1896. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 180–96. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

alternative link at Hathitrust

Primary sources

- Chinese Immigration Pamphlets in the California State Library. Vol. 1 | Vol. 2 | Vol. 3 | Vol. 4,

"Bitter Melon: Inside America's Last Rural Chinese Town" How residents of Locke, California, the last rural Chinese town in America, lived in the Sacramento Delta under the Chinese Exclusion Act

External links

| Wikisource has several original texts related to: Chinese Exclusion Act |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinese Exclusion Act. |

- George Frederick Seward and the Chinese Exclusion Act | "From the Stacks" at New-York Historical Society

- George Frederick Seward Papers, MS 557, The New-York Historical Society

Text of 1880 Chinese Exclusion Treaty and 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act – PBS.org

Chinese Exclusion Act from the Library of Congress

Chinese Exclusion Act – Menlo School

Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) – Our Documents- Exclusion Act Case Files of Yee Wee Thing and Yee Bing Quai, two "Paper Sons"

The Yung Wing Project hosts the memoir of one of the earliest naturalized Chinese whose citizenship was revoked forty-six years after having received it as a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

An Alleged Wife One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era- Collection of primary source documents relating to the Chinese Exclusion Act, from Harvard University.

- Primary source documents and images from the University of California

- The Rocky Road to Liberty: A Documented History of Chinese American Immigration and Exclusion

Primary source documents and images related to the documentary "Separate Lives, Broken Dreams", a saga of the Chinese Exclusion Act era, e.g. political cartoons, immigrant case files and government correspondence from the National Archives.

Risse, Guenter B. (2012). Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco's Chinatown. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421405100. Retrieved 25 June 2018.- Li Bo. Beyond the Heavenly Kingdom is a historical novel that focuses on the politics of the Chinese Exclusion Act

ISBN 1541232216

Chinese Exclusion Act - American Experience PBS playlist on YouTube