0-6-0

| |||||||||||||||||||

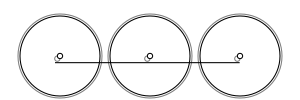

Hackworth's Royal George of 1827 | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 0-6-0 represents the wheel arrangement of no leading wheels, six powered and coupled driving wheels on three axles and no trailing wheels. This was the most common wheel arrangement used on both tender and tank locomotives in versions with both inside and outside cylinders.

In the United Kingdom, the Whyte notation of wheel arrangement was also often used for the classification of electric and diesel-electric locomotives with side-rod coupled driving wheels. Under the UIC classification, popular in Europe, this wheel arrangement is written as C if the wheels are coupled with rods or gears, or Co if they are independently driven, the latter usually being electric and diesel-electric locomotives.[1]

Contents

1 Overview

1.1 History

1.2 Early examples

1.3 Suffixes

2 Usage

2.1 Australia

2.2 Finland

2.3 New Zealand

2.4 South Africa

2.4.1 Cape gauge

2.4.2 Narrow gauges

2.5 South West Africa

2.6 Switzerland

2.7 United Kingdom

2.8 United States of America

3 References

4 External links

Overview

History

The 0-6-0 configuration was the most widely used wheel arrangement for both tender and tank steam locomotives. The type was also widely used for diesel switchers (shunters). Because they lack leading and trailing wheels, locomotives of this type have all their weight pressing down on their driving wheels and consequently have a high tractive effort and factor of adhesion, making them comparatively strong engines for their size, weight and fuel consumption. On the other hand, the lack of unpowered leading wheels have the result that 0-6-0 locomotives are less stable at speed. They are therefore mostly used on trains where high speed is unnecessary.

Since 0-6-0 tender engines can pull fairly heavy trains, albeit slowly, the type was commonly used to pull short and medium distance freight trains such as pickup goods trains along both main and branch lines. The tank engine versions were widely used as switching (shunting) locomotives since the smaller 0-4-0 types were not large enough to be versatile in this job. 0-8-0 and larger switching locomotives, on the other hand, were too big to be economical or even usable on lightly built railways such as dockyards and goods yards, precisely the sorts of places where switching locomotives were most needed.

The earliest 0-6-0 locomotives had outside cylinders, as these were simpler to construct and maintain. However, once designers began to overcome the problem of the breakage of the crank axles, inside cylinder versions were found to be more stable. Thereafter this pattern was widely adopted, particularly in the United Kingdom, although outside cylinder versions were also widely used.

Tank engine versions of the type began to be built in quantity in the mid-1850s and had become very common by the mid-1860s.[2]

Early examples

0-6-0 locomotives were amongst the first types to be used. The earliest recorded example was the Royal George, built by Timothy Hackworth for the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1827.

Other early examples included the Vulcan, the first inside-cylinder type, built by Charles Tayleur and Company in 1835 for the Leicester and Swannington Railway, and Hector, a Long Boiler locomotive, built by Kitson and Company in 1845 for the York and North Midland Railway.[3]

Derwent with a tender at each end

Derwent, a two-tender locomotive built in 1845 by William and Alfred Kitching for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, is preserved at Darlington Railway Centre and Museum.

Suffixes

For a steam tank locomotive, the suffix usually indicates the type of tank or tanks:

- 0-6-0T - side tanks

- 0-6-0ST - saddle tank

- 0-6-0PT - pannier tanks

- 0-6-0WT - well tank

Other steam locomotive suffixes include

- 0-6-0VB - vertical boiler

- 0-6-0F - fireless locomotive

- 0-6-0G - geared steam locomotive

For a diesel locomotive, the suffix indicates the transmission type:

- 0-6-0DM - mechanical transmission

- 0-6-0DH - hydraulic transmission

- 0-6-0DE - electric transmission

Usage

All the major continental European railways used 0-6-0s of one sort or another, though usually not in the proportions used in the United Kingdom. As in the United States, European 0-6-0 locomotives were largely restricted to switching and station pilot duties, though they were also widely used on short branch lines to haul passenger and freight trains. On most branch lines, though, larger and more powerful tank engines tended to be favoured.

Australia

In New South Wales, the Z19 class was a tender type with this wheel arrangement, as was the Victorian Railways Y class.

The Dorrigo Railway Museum collection includes seven Locomotives of the 0-6-0 wheel arrangement, including two Z19 class (1904 and 1923), three 0-6-0 saddle tanks and two 0-6-0 side tanks.

Finland

A handcrafted, 1:8 live steam scale model of a Finnish VR Class Vr1

Tank locomotives used by Finland were the VR Class Vr1 and VR Class Vr4.

The VR Class Vr1s were numbered 530 to 544, 656 to 670 and 787 to 799. They had outside cylinders and were operational from 1913 to 1975. Built by Tampella, Finland and Hanomag (Hannoversche Maschinenbau AG), they were nicknamed Chicken. Number 669 is preserved at the Finnish Railway Museum.

The Vr4s were a class of only four locomotives, numbered 1400 to 1423, originally built as 0-6-0s by Vulcan Iron Works, United States, but modified to 0-6-2s in 1951-1955, and re-classified as Vr5.

Restored VR Class C1 no. 21 at the Finnish Railway Museum

Finland’s tender locomotives were the classes C1, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6.

The Finnish Steam Locomotive Class C1s were a class of ten locomotives numbered 21 to 30. They were operational from 1869 to 1926. They were built by Neilson and Company and were nicknamed Bristollari. Number 21, preserved at the Finnish Railway Museum, is the second oldest preserved locomotive in Finland.

The eighteen Class C2s were numbered 31 to 43 and 48 to 52. They were also nicknamed Bristollari.

The C3 was a class of only two locomotives, numbered 74 and 75.

The thirteen Class C4s were numbered 62 and 78 to 89.

The fourteen Finnish Steam Locomotive Class C5s were numbered 101 to 114. They were operational from 1881 to 1930. They were built by Hanomag in Hannover and were nicknamed Bliksti. No 110 is preserved at the Finnish Railway Museum.

The C6 was a solitary class of one locomotive, numbered 100.

New Zealand

In New Zealand the 0-6-0 design was restricted to tank engines. The Hunslet-built M class of 1874 and Y class of 1923 provided 7 examples, however the F class built between 1872 and 1888 was the most prolific, surviving the entire era of NZR steam operations, with 88 examples of which 8 were preserved.

South Africa

Cape gauge

In 1876, the Cape Government Railways (CGR) placed a pair of 0-6-0 Stephenson’s Patent permanently coupled back-to-back tank locomotives in service on the Cape Eastern system. They worked out of East London in comparative trials with the experimental 0-6-0+0-6-0 Fairlie locomotive that was acquired in that same year.[4][5][6]

Natal Harbours Department locomotive John Milne

The Natal Harbours Department placed a single 0-6-0 saddle-tank locomotive in service in 1879, named John Milne.[7][8]

The Natal Government Railways placed a single locomotive in shunting service in 1880, later designated Class K, virtually identical to the Durban Harbour's John Milne and built by the same manufacturer.[7][8]

In 1882, two 0-6-0 tank locomotives entered service on the private Kowie Railway between Grahamstown and Port Alfred. Both locomotives were rebuilt to a 4-4-0T wheel arrangement in 1884.[4]

In 1890, the Nederlandsche-Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg-Maatschappij of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (Transvaal Republic) placed six 18 Tonner 0-6-0ST locomotives in service on construction work.[4]

In 1896 and 1897, three 26 Tonner saddle-tank locomotives were built for the Pretoria-Pietersburg Railway (PPR) by Hawthorn, Leslie and Company. These were the first locomotives to be obtained by the then recently established PPR. Two of these, named Nylstroom and Pietersburg, came into SAR stock in 1912 and survived into the 1940s.[4][8][9]

Harbour locomotive Edward Innes

In 1901, a single 0-6-0T harbour locomotive built by Hudswell, Clarke was delivered to the Harbours Department of Natal. It was named Edward Innes and retained this name when it was taken onto the SAR roster in 1912.[7][8][9]

Two saddle-tank locomotives were supplied to the East London Harbour Board in 1902, built by Hunslet. Both survived until the 1930s, well into the SAR era.[7][8]

In 1904, a single saddle tank harbour locomotive, named Sir Albert, was built by Hunslet for the Harbours Department of Natal. It came into SAR stock in 1912 and was withdrawn in 1915.[7][8][9]

Narrow gauges

In 1871, two 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauge tank locomotives, built by the Lilleshall Company of Oakengates, Shropshire in 1870 and 1871, were placed in service by the Cape of Good Hope Copper Mining Company. Named John King and Miner, they were the first steam locomotives to enter service on the hitherto mule-powered Namaqualand Railway between Port Nolloth and the Namaqualand copper mines around O'okiep in the Cape Colony.[10]

In 1902, Arthur Koppel, acting as agent, imported a single 0-6-0 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge tank steam locomotive for a customer in Durban. It was then purchased by the Cape Government Railways and used as construction locomotive on the Avontuur branch from 1903. In 1912, this locomotive was assimilated into the South African Railways and in 1917 it was sent to German South West Africa during the First World War campaign in that territory.[5][8]

South West Africa

Krauss factory picture of Zwillinge 73 A & B, c. 1899

Between 1898 and 1905, more than fifty pairs of Zwillinge twin tank steam locomotives were acquired by the Swakopmund-Windhuk Staatsbahn (Swakopmund-Windhoek State Railway) in Deutsch-Südwest-Afrika (DSWA, now Namibia). Zwillinge locomotives were a class of small 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) Schmalspur (narrow gauge) 0-6-0T tank steam locomotives that were built in Germany in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As indicated by their name Zwillinge (twins), they were designed to be used in pairs, semi-permanently coupled back-to-back at the cabs, allowing a single footplate crew to fire and control both locomotives. The pairs of locomotives shared a common manufacturer’s works number and engine number, with the units being designated as A and B. By 1922, when the SAR took control of all railway operations in South West Africa (SWA), only two single Illinge locomotives survived to be absorbed onto the roster of the SAR.[8]

In 1907, the German Administration in DSWA acquired three Class Hc tank locomotives for the narrow gauge Otavi Mining and Railway Company. One more entered service in 1910, and another was obtained by the South African Railways in 1929.[8]

In 1911, the Lüderitzbucht Eisenbahn (Lüderitzbucht Railway) placed two Cape gauge 0-6-0T locomotives in service as shunting engines. They were apparently no longer in service when all railways in the territory came under the administration of the South African Railways in 1922.[11]

Switzerland

During the Second World War, Switzerland converted some 0-6-0 shunting engines into electric-steam locomotives.

United Kingdom

The 0-6-0 tender locomotive type was extremely common in Britain for more than a century and was still being built in large numbers during the 1940s. Between 1858 and 1872, 943 examples of the John Ramsbottom DX goods class were built by the London and North Western Railway and the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. This was the earliest example of standardisation and mass production of locomotives.[12]

Preserved Class Q1 no. 33001

Of the total stock of standard-gauge locomotives operating on British railways in 1900, around 20,000 engines, over a third were 0-6-0 tender types. The ultimate British 0-6-0 was the Q1 Austerity type, developed by the Southern Railway during the Second World War to haul very heavy freight trains. It was the most powerful steam 0-6-0 design produced in Europe.

Similarly, the 0-6-0 tank locomotives became the most common locomotive type on all railways throughout the 20th century. All of the Big Four companies to emerge from the Railways Act, 1921 grouping used them in vast numbers. The Great Western Railway, in particular, had many of the type, most characteristically in the form of the pannier tank locomotive that remained in production well past railway nationalisation in 1948.

When diesel shunters began to be introduced, the 0-6-0 type became the most common. Many of the British Railways shunter types were 0-6-0s, including Class 03, the standard light shunter, and Class 08 and Class 09, the standard heavier shunters.

United States of America

In the United States, huge numbers of 0-6-0 locomotives were produced, with the majority of them being used as switchers. The USRA 0-6-0 was the smallest of the USRA Standard classes designed and produced during the brief government control of the railroads through the USRA during the First World War. 255 of them were built and ended up in the hands of about two dozen United States railroads.

A USRA 0-6-0

In addition, many of the railroads (and others) built numerous copies after the war. The Pennsylvania Railroad rostered over 1,200 0-6-0 types over the years, which were classed as class B on that system. The United States 0-6-0s were generally tender locomotives.

During the Second World War, no fewer than 514 USATC S100 Class 0-6-0 tank engines were built by the Davenport Locomotive Works, for use by the United States Army Transportation Corps in both Europe and North Africa. Some of these remained in service long after the war, having been purchased or otherwise adopted by the countries where they were used. These included Austria, Egypt, France, Iraq, the United Kingdom and Yugoslavia.

The fourteen engines purchased by the Southern Railway in 1946 remained in service well into the 1960s. Designed to be extremely strong but easy to maintain, these engines had a very short wheelbase that allowed them to operate on dockyard railways.

References

^ Whyte notation

^ Bertram Baxter, British locomotive catalogue 1825-1923, Vol.1, Moorland Publishing, 1977.

^ The Science Museum, The British railway locomotive 1803-1850, H.M.S.O., 1958.

^ abcd Holland, D.F. (1971). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways. 1: 1859–1910 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, Devon: David & Charles. pp. 25–28, 80–83, 110, 118. ISBN 978-0-7153-5382-0..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab Dulez, Jean A. (2012). Railways of Southern Africa 150 Years (Commemorating One Hundred and Fifty Years of Railways on the Sub-Continent – Complete Motive Power Classifications and Famous Trains – 1860–2011) (1st ed.). Garden View, Johannesburg, South Africa: Vidrail Productions. pp. 21–22, 232. ISBN 9 780620 512282.

^ What were these, 2-6-0T or 0-6-0T?

^ abcde Holland, D. F. (1972). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways. 2: 1910-1955 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, Devon: David & Charles. pp. 120, 125–129, 131. ISBN 978-0-7153-5427-8.

^ abcdefghi Paxton, Leith; Bourne, David (1985). Locomotives of the South African Railways (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 21–24, 26, 111–112, 116–117, 121, 157. ISBN 0869772112.

^ abc Classification of S.A.R. Engines with Renumbering Lists, issued by the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s Office, Pretoria, January 1912, pp. 2, 11, 13 (Reprinted in April 1987 by SATS Museum, R.3125-6/9/11-1000)

^ Bagshawe, Peter (2012). Locomotives of the Namaqualand Railway and Copper Mines (1st ed.). Stenvalls. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-91-7266-179-0.

^ Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1948). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VII - South African Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, January 1948. p. 31.

^ H.C. Casserley, The historic locomotive pocket book, Batsford, 1960, p.23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 0-6-0. |

Building a 1/8 scale Live Steam 0-6-0 locomotive This site includes a full 1914 factory drawing of a Finnish 0-6-0 switcher.