Criminology

Criminology and penology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Theory

| |||

Types of crime

| |||

Penology

| |||

Schools

| |||

| Sociology |

|---|

|

|

Main theories |

|

Methods |

|

Subfields and other major theories |

|

Browse |

|

Three women in the pillory, China, 1875

Criminology (from Latin crīmen, "accusation" originally derived from the Ancient Greek verb "krino" "κρίνω", and Ancient Greek -λογία, -logy|-logia, from "logos" meaning: “word,” “reason,” or “plan”) is the scientific study of the nature, extent, management, causes, control, consequences, and prevention of criminal behavior, both on individual and social levels. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioral and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, biologists, social anthropologists, as well as scholars of law.

The term criminology was coined in 1885 by Italian law professor Raffaele Garofalo as criminologia. Later, French anthropologist Paul Topinard used the analogous French term criminologie.[1]

From 1900 through to 2000 the study underwent three significant phases in the United States: (1) Golden Age of Research (1900-1930)-which has been described as a multiple-factor approach, (2) Golden Age of Theory (1930-1960)-which shows that there was no systematic way of connecting criminological research to theory, and (3) a 1960-2000 period-which was seen as a significant turning point for criminology.[2]

Contents

1 Criminological Schools of thought

1.1 Classical school

1.2 Positivist school

1.2.1 Italian school

1.2.2 Sociological positivism

1.2.3 Differential association (subcultural)

1.3 Chicago school

1.4 Social structure theories

1.4.1 Social disorganization (neighborhoods)

1.4.2 Social ecology

1.4.3 Strain theory (social strain theory)

1.4.4 Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Anomie Theory

1.4.5 Subcultural theory

1.4.6 Control theories

1.4.7 Psychoanalysis and the unconscious desire for punishment

2 Social network analysis

2.1 Symbolic interactionism

2.1.1 Labeling theory

2.2 Individual theories

2.2.1 Traitor theories

2.2.2 Rational choice theory

2.2.3 Routine activity theory

2.3 Biosocial theories

2.4 Marxist criminology

2.5 Convict Criminology

2.6 Queer Criminology

2.6.1 Cultural Criminology

3 Relative Deprivation Theory

4 Rural Criminology

5 Types and definitions of crime

6 Subtopics

7 See also

8 References

8.1 Notes

8.2 Bibliography

9 External links

Criminological Schools of thought

In the mid-18th century, criminology arose as social philosophers gave thought to crime and concepts of law. Over time, several schools of thought have developed. There were three main schools of thought in early criminological theory spanning the period from the mid-18th century to the mid-twentieth century: Classical, Positivist, and Chicago. These schools of thought were superseded by several contemporary paradigms of criminology, such as the sub-culture, control, strain, labeling, critical criminology, cultural criminology, postmodern criminology, feminist criminology and others discussed below.

Classical school

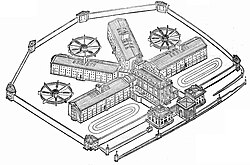

The Classical school arose in the mid-18th century and has its basis in utilitarian philosophy. Cesare Beccaria,[3] author of On Crimes and Punishments (1763–64), Jeremy Bentham (inventor of the panopticon), and other philosophers in this school argued:[citation needed]

- People have free will to choose how to act.

- The basis for deterrence is the idea humans are 'hedonists' who seek pleasure and avoid pain and 'rational calculators' who weigh the costs and benefits of every action. It ignores the possibility of irrationality and unconscious drives as 'motivators'.

Punishment (of sufficient severity) can deter people from crime, as the costs (penalties) outweigh benefits, and severity of punishment should be proportionate to the crime.[3]- The more swift and certain the punishment, the more effective as a deterrent to criminal behavior.

This school developed during a major reform in penology when society began designing prisons for the sake of extreme punishment. This period also saw many legal reforms, the French Revolution, and the development of the legal system in the United States.[citation needed]

Positivist school

The Positivist school argues criminal behavior comes from internal and external factors out of the individual's control. Philosophers within this school applied the scientific method to study human behavior. Positivism comprises three segments: biological, psychological and social positivism.[4]

Italian school

Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), an Italian sociologist working in the late 19th century, is often called "the father of criminology."[5] He was one of the key contributors to biological positivism and founded the Italian school of criminology.[6] Lombroso took a scientific approach, insisting on empirical evidence for studying crime.[7] He suggested physiological traits such as the measurements of cheekbones or hairline, or a cleft palate could indicate "atavistic" criminal tendencies. This approach, whose influence came via the theory of phrenology and by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, has been superseded. Enrico Ferri, a student of Lombroso, believed social as well as biological factors played a role, and believed criminals should not be held responsible when factors causing their criminality were beyond their control. Criminologists have since rejected Lombroso's biological theories since control groups were not used in his studies.[8][9]

Sociological positivism

Sociological positivism suggests societal factors such as poverty, membership of subcultures, or low levels of education can predispose people to crime. Adolphe Quetelet used data and statistical analysis to study the relationship between crime and sociological factors. He found age, gender, poverty, education, and alcohol consumption were important factors to crime.[10] Lance Lochner performed three different research experiments, each one proving education reduces crime.[11]Rawson W. Rawson used crime statistics to suggest a link between population density and crime rates, with crowded cities producing more crime.[12]Joseph Fletcher and John Glyde read papers to the Statistical Society of London on their studies of crime and its distribution.[13]Henry Mayhew used empirical methods and an ethnographic approach to address social questions and poverty, and gave his studies in London Labour and the London Poor.[14]Émile Durkheim viewed crime as an inevitable aspect of a society with uneven distribution of wealth and other differences among people.

Differential association (subcultural)

Differential association (subcultural) posits that people learn crime through association. This theory was advocated by Edwin Sutherland.[15] These acts may condone criminal conduct, or justify crime under specific circumstances. Interacting with antisocial peers is a major cause. Reinforcing criminal behavior makes it chronic. Where there are criminal subcultures, many individuals learn crime, and crime rates swell in those areas.[16]

Chicago school

The Chicago school arose in the early twentieth century, through the work of Robert E. Park, Ernest Burgess, and other urban sociologists at the University of Chicago. In the 1920s, Park and Burgess identified five concentric zones that often exist as cities grow, including the "zone of transition", which was identified as the most volatile and subject to disorder. In the 1940s, Henry McKay and Clifford R. Shaw focused on juvenile delinquents, finding that they were concentrated in the zone of transition.

Chicago school sociologists adopted a social ecology approach to studying cities and postulated that urban neighborhoods with high levels of poverty often experience a breakdown in the social structure and institutions, such as family and schools. This results in social disorganization, which reduces the ability of these institutions to control behavior and creates an environment ripe for deviant behavior.

Other researchers suggested an added social-psychological link. Edwin Sutherland suggested that people learn criminal behavior from older, more experienced criminals with whom they may associate.

Theoretical perspectives used in criminology include psychoanalysis, functionalism, interactionism, Marxism, econometrics, systems theory, postmodernism, genetics, neuropsychology, evolutionary psychology, etc.

Social structure theories

This theory is applied to a variety of approaches within the bases of criminology in particular and in sociology more generally as a conflict theory or structural conflict perspective in sociology and sociology of crime. As this perspective is itself broad enough, embracing as it does a diversity of positions.[17]

Social disorganization (neighborhoods)

Social disorganization theory is based on the work of Henry McKay and Clifford R. Shaw of the Chicago School.[18] Social disorganization theory postulates that neighborhoods plagued with poverty and economic deprivation tend to experience high rates of population turnover.[19] This theory suggests that crime and deviance is valued within groups in society, ‘subcultures’ or ‘gangs’. These groups have different values to the social norm. These neighborhoods also tend to have high population heterogeneity.[19] With high turnover, informal social structure often fails to develop, which in turn makes it difficult to maintain social order in a community.

Social ecology

Since the 1950s, social ecology studies have built on the social disorganization theories. Many studies have found that crime rates are associated with poverty, disorder, high numbers of abandoned buildings, and other signs of community deterioration.[19][20] As working and middle-class people leave deteriorating neighborhoods, the most disadvantaged portions of the population may remain. William Julius Wilson suggested a poverty "concentration effect", which may cause neighborhoods to be isolated from the mainstream of society and become prone to violence.[21]

Strain theory (social strain theory)

Strain theory, also known as Mertonian Anomie, advanced by American sociologist Robert Merton, suggests that mainstream culture, especially in the United States, is saturated with dreams of opportunity, freedom, and prosperity—as Merton put it, the American Dream. Most people buy into this dream, and it becomes a powerful cultural and psychological motivator. Merton also used the term anomie, but it meant something slightly different for him than it did for Durkheim. Merton saw the term as meaning a dichotomy between what society expected of its citizens and what those citizens could actually achieve. Therefore, if the social structure of opportunities is unequal and prevents the majority from realizing the dream, some of those dejected will turn to illegitimate means (crime) in order to realize it. Others will retreat or drop out into deviant subcultures (such as gang members, or what he calls "hobos"). Robert Agnew developed this theory further to include types of strain which were not derived from financial constraints. This is known as general strain theory".[22]

Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Anomie Theory

The Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Theory stems from a pre-existing theory, one that was discovered by Merton, named Strain theory. Rosenberger took his findings from it and offered a different approach to the definition. It was based on the notion that everybody should already have "the assumption that the “American Dream” produces a society that is dominated by the economy and obsessed with the pursuit of success."[23] The Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Theory has many different views and definitions by many people, therefore, this becomes a very flexible theory.

Larine Hughes found a correlation between economic pressure and how it links the "American Dream" and "Individualism" to a high crime. Hughes came to final decision that "Therefore, individuals that do not have the drive to succeed and achieve this “goal”[24] will fail, despite social and cultural pressures.[citation needed]

Samantha Applin then took an approach relating genders and The Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Theory. Stated in an article by S. Applin, "males make up what is considered “normal subjects”, and due to this, force woman to lie on a boundary that expectation is outside the dominant cultural frame."[25] Therefore, setting women back in the beginning stages of Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Theory.[citation needed]

Brian Stults began to research studies on the violence between youth and the correlation that it has on Messner and Rosenfeld Institutional Anomie Theory. Stults stated, " As well as the results showed graduating high school represents an important developmental stage in American society, as it ends the compulsory education, and is often followed by a significant decline in daily need and extra resources from your parents."[citation needed]

Subcultural theory

Following the Chicago school and strain theory, and also drawing on Edwin Sutherland's idea of differential association, sub-cultural theorists focused on small cultural groups fragmenting away from the mainstream to form their own values and meanings about life.

Albert K. Cohen tied anomie theory with Sigmund Freud's reaction formation idea, suggesting that delinquency among lower-class youths is a reaction against the social norms of the middle class.[26] Some youth, especially from poorer areas where opportunities are scarce, might adopt social norms specific to those places that may include "toughness" and disrespect for authority. Criminal acts may result when youths conform to norms of the deviant subculture.[27]

Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin suggested that delinquency can result from a differential opportunity for lower class youth.[28] Such youths may be tempted to take up criminal activities, choosing an illegitimate path that provides them more lucrative economic benefits than conventional, over legal options such as minimum wage-paying jobs available to them.[28]

Delinquency tends to occur among the lower-working-class males who have a lack of resources available to them and live in impoverished areas, as mentioned extensively by Albert Cohen (Cohen, 1965). Bias has been known to occur among law enforcement agencies, where officers tend to place a bias on minority groups, without knowing for sure if they had committed a crime or not. Delinquents may also commit crimes in order to secure funds for themselves or their loved ones, such as committing an armed robbery, as studied by many scholars (Briar & Piliavin).[citation needed]

British sub-cultural theorists focused more heavily on the issue of class, where some criminal activities were seen as "imaginary solutions" to the problem of belonging to a subordinate class. A further study by the Chicago school looked at gangs and the influence of the interaction of gang leaders under the observation of adults.

Sociologists such as Raymond D. Gastil have explored the impact of a Southern culture of honor on violent crime rates.[29]

Control theories

Another approach is made by the social bond or social control theory. Instead of looking for factors that make people become criminal, these theories try to explain why people do not become criminal. Travis Hirschi identified four main characteristics: "attachment to others", "belief in moral validity of rules", "commitment to achievement", and "involvement in conventional activities".[30] The more a person features those characteristics, the less likely he or she is to become deviant (or criminal). On the other hand, if these factors are not present, a person is more likely to become a criminal. Hirschi expanded on this theory with the idea that a person with low self-control is more likely to become criminal. As opposed to most criminology theories, these do not look at why people commit crime but rather why they do not commit crime.[31]

A simple example: Someone wants a big yacht but does not have the means to buy one. If the person cannot exert self-control, he or she might try to get the yacht (or the means for it) in an illegal way, whereas someone with high self-control will (more likely) either wait, deny themselves of what want or seek an intelligent intermediate solution, such as joining a yacht club to use a yacht by group consolidation of resources without violating social norms.

Social bonds, through peers, parents, and others can have a countering effect on one's low self-control. For families of low socio-economic status, a factor that distinguishes families with delinquent children, from those who are not delinquent, is the control exerted by parents or chaperonage.[32] In addition, theorists such as David Matza and Gresham Sykes argued that criminals are able to temporarily neutralize internal moral and social behavioral constraints through techniques of neutralization.

Psychoanalysis and the unconscious desire for punishment

see main article Psychoanalytic criminology

Psychoanalysis is a psychological theory (and therapy) which regards the unconscious mind, repressed memories and trauma, as the key drivers of behavior, especially deviant behavior.[33]Sigmund Freud talks about how the unconscious desire for pain relates to psychoanalysis in his novel, Beyond the Pleasure Principle,.[33] Freud suggested that unconscious impulses such as ‘repetition compulsion’ and a ‘death drive’ can dominate a person's creativity, leading to self-destructive behavior. Phillida Rosnick, in the article Mental Pain and Social Trauma, posits a difference in the thoughts of individuals suffering traumatic unconscious pain which corresponds to them having thoughts and feelings which are not reflections of their true selves. There is enough correlation between this altered state of mind and criminality to suggest causation.[34]Sander Gilman, in the article Freud and the Making of Psychoanalysis, looks for evidence in the physical mechanisms of the human brain and the nervous system and suggests there is a direct link between an unconscious desire for pain or punishment and the impulse to commit crime or deviant acts.[35][35]

Social network analysis

Symbolic interactionism

Symbolic interactionism draws on the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and George Herbert Mead, as well as subcultural theory and conflict theory.[36] This school of thought focused on the relationship between state, media, and conservative-ruling elite and other less powerful groups. The powerful groups had the ability to become the "significant other" in the less powerful groups' processes of generating meaning. The former could to some extent impose their meanings on the latter; therefore they were able to "label" minor delinquent youngsters as criminal. These youngsters would often take the label on board, indulge in crime more readily, and become actors in the "self-fulfilling prophecy" of the powerful groups. Later developments in this set of theories were by Howard Becker and Edwin Lemert, in the mid-20th century.[37]Stanley Cohen developed the concept of "moral panic" describing the societal reaction to spectacular, alarming social phenomena (e.g. post-World War 2 youth cultures like the Mods and Rockers in the UK in 1964, AIDS epidemic and football hooliganism).

Labeling theory

Labeling theory refers to an individual who is labeled in a particular way and was studied in great detail by Becker.[38] It arrives originally from sociology but is regularly used in criminological studies. It is said that when someone is given the label of a criminal they may reject or accept it and continue to commit crime. Even those who initially reject the label can eventually accept it as the label becomes more well known, particularly among their peers. This stigma can become even more profound when the labels are about deviancy, and it is thought that this stigmatization can lead to deviancy amplification. Malcolm Klein conducted a test which showed that labeling theory affected some youth offenders but not others.[39]

Individual theories

The self-assessment of the perpetrator of the Bath School disaster

Traitor theories

At the other side of the spectrum, criminologist Lonnie Athens developed a theory about how a process of brutalization by parents or peers that usually occurs in childhood results in violent crimes in adulthood. Richard Rhodes' Why They Kill describes Athens' observations about domestic and societal violence in the criminals' backgrounds. Both Athens and Rhodes reject the genetic inheritance theories.[40]

Rational choice theory

Cesare Beccaria

Rational choice theory is based on the utilitarian, classical school philosophies of Cesare Beccaria, which were popularized by Jeremy Bentham. They argued that punishment, if certain, swift, and proportionate to the crime, was a deterrent for crime, with risks outweighing possible benefits to the offender. In Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crimes and Punishments, 1763–1764), Beccaria advocated a rational penology. Beccaria conceived of punishment as the necessary application of the law for a crime; thus, the judge was simply to confirm his or her sentence to the law. Beccaria also distinguished between crime and sin, and advocated against the death penalty, as well as torture and inhumane treatments, as he did not consider them as rational deterrents.

This philosophy was replaced by the positivist and Chicago schools and was not revived until the 1970s with the writings of James Q. Wilson, Gary Becker's 1965 article Crime and Punishment[41] and George Stigler's 1970 article The Optimum Enforcement of Laws.[42] Rational choice theory argues that criminals, like other people, weigh costs or risks and benefits when deciding whether to commit crime and think in economic terms.[43] They will also try to minimize risks of crime by considering the time, place, and other situational factors.[43]

Becker, for example, acknowledged that many people operate under a high moral and ethical constraint but considered that criminals rationally see that the benefits of their crime outweigh the cost, such as the probability of apprehension and conviction, severity of punishment, as well as their current set of opportunities. From the public policy perspective, since the cost of increasing the fine is marginal to that of the cost of increasing surveillance, one can conclude that the best policy is to maximize the fine and minimize surveillance.

With this perspective, crime prevention or reduction measures can be devised to increase the effort required to commit the crime, such as target hardening.[44] Rational choice theories also suggest that increasing risk and likelihood of being caught, through added surveillance, law enforcement presence, added street lighting, and other measures, are effective in reducing crime.[44]

One of the main differences between this theory and Bentham's rational choice theory, which had been abandoned in criminology, is that if Bentham considered it possible to completely annihilate crime (through the panopticon), Becker's theory acknowledged that a society could not eradicate crime beneath a certain level. For example, if 25% of a supermarket's products were stolen, it would be very easy to reduce this rate to 15%, quite easy to reduce it until 5%, difficult to reduce it under 3% and nearly impossible to reduce it to zero (a feat which the measures required would cost the supermarket so much that it would outweigh the benefits). This reveals that the goals of utilitarianism and classical liberalism have to be tempered and reduced to more modest proposals to be practically applicable.

Such rational choice theories, linked to neoliberalism, have been at the basics of crime prevention through environmental design and underpin the Market Reduction Approach to theft [45] by Mike Sutton, which is a systematic toolkit for those seeking to focus attention on "crime facilitators" by tackling the markets for stolen goods[46] that provide motivation for thieves to supply them by theft.[47]

Routine activity theory

Routine activity theory, developed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence Cohen, draws upon control theories and explains crime in terms of crime opportunities that occur in everyday life.[48] A crime opportunity requires that elements converge in time and place including a motivated offender, suitable target or victim, and lack of a capable guardian.[49] A guardian at a place, such as a street, could include security guards or even ordinary pedestrians who would witness the criminal act and possibly intervene or report it to law enforcement.[49] Routine activity theory was expanded by John Eck, who added a fourth element of "place manager" such as rental property managers who can take nuisance abatement measures.[50]

Biosocial theories

Biosocial criminology is an interdisciplinary field that aims to explain crime and antisocial behavior by exploring both biological factors and environmental factors. While contemporary criminology has been dominated by sociological theories, biosocial criminology also recognizes the potential contributions of fields such as genetics, neuropsychology, and evolutionary psychology.[51]

Aggressive behavior has been associated with abnormalities in three principal regulatory systems in the body: serotonin systems, catecholamine systems, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Abnormalities in these systems also are known to be induced by stress, either severe, acute stress or chronic low-grade stress.[52]

Marxist criminology

In 1968, young British sociologists formed the National Deviance Conference (NDC) group. The group was restricted to academics and consisted of 300 members. Ian Taylor, Paul Walton and Jock Young – members of the NDC – rejected previous explanations of crime and deviance. Thus, they decided to pursue a new Marxist criminological approach.[53] In The New Criminology, they argued against the biological "positivism" perspective represented by Lombroso, Hans Eysenck and Gordon Trasler.[54]

According to the Marxist perspective on crime, "defiance is normal – the sense that men are now consciously involved [...] in assuring their human diversity." Thus Marxists criminologists argued in support of society in which the facts of human diversity, be it social or personal, would not be criminalized.[55] They further attributed the processes of crime creation not to genetic or psychological facts, but rather to the material basis of a given society.[56]

Convict Criminology

Convict criminology is a school of thought in the realm of criminology. Convict criminologists have been directly affected by the criminal justice system, oftentimes having spent years inside the prison system. Researchers in the field of convict criminology such as John Irwin and Stephan Richards argue that traditional criminology can better be understood by those who lived in the walls of a prison.[57] Martin Leyva argues that "prisonization" oftentimes begins before prison, in the home, community, and schools.[58]

According to Rod Earle, Convict Criminology started in the United states after the major expansion of prisons in the 1970's. So the U.S still remains the main focus for those who study convict criminology. [59]

Queer Criminology

Queer criminology is a field of study that focuses on LGBT individuals and their interactions with the criminal justice system. The goals of this field of study are as follows:

- To better understand the history of LGBT individuals and the laws put against the community

- Why LGBT citizens are incarcerated and if or why they are arrested at higher rates than heterosexual and cisgender individuals

- How queer activists have fought against oppressive laws that criminalized LGBT individuals

- To conduct research and use it as a form of activism through education

Legitimacy of Queer criminology:

The value of pursuing criminology from a queer theorist perspective is contested; some believe that it is not worth researching and not relevant to the field as a whole, and as a result is a subject that lacks a wide berth of research available. On the other hand, it could be argued that this subject is highly valuable in highlighting how LGBT individuals are affected by the criminal justice system. This research also has the opportunity to “queer” the curriculum of criminology in educational institutions by shifting the focus from controlling and monitoring LGBT communities to liberating and protecting them.[60]

Cultural Criminology

This section may require copy editing. (December 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Cultural criminology theory looks at how crime affects the social and cultural environment.[61][62] Ferrell believes criminologists can examine the actions of criminals, control agents, media producers, and others to collectively construct the meaning of crime.[62] He discussed that these actions were a way to show dominance towards society and the way things are run.[62] Kane adds that cultural criminology has three tropes; village, city street, and mass media where males can be geographically influenced by society's views on what is broadcast and accepted as right or wrong.[63] The village where one engages in available social activities. By linking the history of an individual to a location can help determine social dynamics.[63] The city street involves positioning oneself in the cultural area. These are full of those affected by poverty, poor health and crime, and large buildings that impact the city but not neighborhoods.[63] Mass media gives an all around account of the environment and the possible other subcultures that could exist beyond a specific geographical area.[63] It was later that Naegler and Salman introduced feminist theory to cultural criminology and discussed masculinity and femininity, sexual attraction and sexuality, and intersectional themes.[64] Naegler and Salman believed that Ferrell's mold was limited and that they could add to the understanding of cultural criminology by studying women and those who do not fit Ferrell's mold.[64] Hayward would later add that not only feminist theory, but the green theory played a role in the cultural criminology theory through the lens of adrenaline, the soft city, the transgressive subject, and the attentive gaze.[61] The adrenaline lens deals with rational choice and what causes a person to have their own terms of availability, opportunity, and low levels of social control.[61] The soft city lens deals with reality outside of the city and imaginary sense of reality; the world where transgression occurs, where rigidity is slanted, and where rules are bent.[61] The transgressive subject is attracted to rule breaking and is attempting to be themselves in a world where everyone is against them.[61] The attentive gaze is when someone, mainly an ethnography, is immersed into the culture and interested in lifestyle(s), the symbolic, the aesthetic, and the visual aspects. When examined, they are left with the knowledge that they are not all the same, but come to a settlement of living together in the same space.[61] Through it all, sociological perspective on cultural criminology theory attempts to understand how the environment an individual is in determines their criminal behavior.[62]

Relative Deprivation Theory

Relative deprivation involves the process where an individual measures his or her own well-being and materialistic worth against that of other people and perceive that they are worse off in comparison.[65] When humans fail to obtain what they believe they are owed, they can experience anger or jealousy over the notion that they have been wrongly disadvantaged.

Relative deprivation was originally utilized in the field of sociology by Samuel A. Stouffer, who was a pioneer of this theory. Stouffer revealed that soldiers fighting in World War II measured their personal success by the experience in their units rather than by the standards set by the military.[66] Relative deprivation can be made up of societal, political, economic, or personal factors which create a sense of injustice. It is not based on absolute poverty, a condition where one cannot meet a necessary level to maintain basic living standards. Rather, relative deprivation enforces the idea that even if a person is financially stable, he or she can still feel relatively deprived. The perception of being relatively deprived can result in criminal behavior and/or morally problematic decisions.[67] Relative deprivation theory has increasingly been used to partially explain crime as rising living standards can result in rising crime levels. In criminology, the theory of relative deprivation explains that people who feel jealous and discontent of others might turn to crime to acquire the things that they can not afford.

Rural Criminology

Rural criminology is the study of crime trends outside of metropolitan and suburban areas. Rural criminologists have used social disorganization and routine activity theories. The FBI Uniform Crime Report shows that rural communities have significantly different crime trends as opposed to metropolitan and suburban areas. The crime in rural communities consists predominantly of narcotic related crimes such as the production, use, and trafficking of narcotics. Social disorganization theory is used to examine the trends involving narcotics.[68] Social disorganization leads to narcotic use in rural areas because of low educational opportunities and high unemployment rates. routine activity theory is used to examine all low level street crimes such as theft.[69] Much of the crime in rural areas is explained through routine activity theory because there is often a lack of capable guardians in rural areas.[citation needed]

Types and definitions of crime

Both the positivist and classical schools take a consensus view of crime: that a crime is an act that violates the basic values and beliefs of society. Those values and beliefs are manifested as laws that society agrees upon. However, there are two types of laws:

Natural laws are rooted in core values shared by many cultures. Natural laws protect against harm to persons (e.g. murder, rape, assault) or property (theft, larceny, robbery), and form the basis of common law systems.

Statutes are enacted by legislatures and reflect current cultural mores, albeit that some laws may be controversial, e.g. laws that prohibit cannabis use and gambling. Marxist criminology, conflict criminology, and critical criminology claim that most relationships between state and citizen are non-consensual and, as such, criminal law is not necessarily representative of public beliefs and wishes: it is exercised in the interests of the ruling or dominant class. The more right-wing criminologies tend to posit that there is a consensual social contract between state and citizen.

Therefore, definitions of crimes will vary from place to place, in accordance to the cultural norms and mores, but may be broadly classified as a blue-collar crime, corporate crime, organized crime, political crime, public order crime, state crime, state-corporate crime, and white-collar crime.[70] However, there have been moves in contemporary criminological theory to move away from liberal pluralism, culturalism, and postmodernism by introducing the universal term "harm" into the criminological debate as a replacement for the legal term "crime".[71]

[72]

Subtopics

Areas of study in criminology include:

- Comparative criminology, which is the study of the social phenomenon of crime across cultures, to identify differences and similarities in crime patterns.[73]

- Crime prevention

- Crime statistics

- Criminal behavior

- Criminal careers and desistance

- Domestic violence

- Deviant behavior

Evaluation of criminal justice agencies- Fear of crime

- The International Crime Victims Survey

- Juvenile delinquency

- Penology

- Sociology of law

- Victimology

See also

- American Society of Criminology

- Anthropological criminology

- Asian Criminological Society

- Australia/New Zealand Society of Criminology

- British Society of Criminology

- Crime science

- European Society of Criminology

- Forensic psychology

- Forensic science

- List of criminologists

- Social cohesion

- The Mask of Sanity

- Taboo

References

Notes

^ Deflem, Mathieu, ed. (2006). Sociological Theory and Criminological Research: Views from Europe and the United States. Elsevier. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-7623-1322-8..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Braithwaite, J. (2000-03-01). "The New Regulatory State and the Transformation of Criminology". British Journal of Criminology. 40 (2): 222–238. doi:10.1093/bjc/40.2.222. ISSN 0007-0955.

^ ab Beccaria, Cesare (1764). On Crimes and Punishments, and Other Writings. Translated by Richard Davies. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-521-40203-3.

^ David, Christian Carsten. "Criminology - Crime." Cybercrime. Northamptonshire (UK), 5 June 1972. Web. 23 February 2012. <http://carsten-ulbrich.zymichost.com/crimeanalysis/10.html[permanent dead link]>.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Siegel, Larry J. (2003). Criminology, 8th edition. Thomson-Wadsworth. p. 7.

^ McLennan, Gregor; Jennie Pawson; Mike Fitzgerald (1980). Crime and Society: Readings in History and Theory. Routledge. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-415-02755-7.

^

Siegel, Larry J. (2003). Criminology, 8th edition. Thomson-Wadsworth. p. 139.

^

Compare: Siegel, Larry J. (2015-01-01). Criminology: Theories, Patterns, and Typologies (12 ed.). Cengage Learning (published 2015). p. 135. ISBN 9781305446090. Retrieved 2015-05-29.The work of Lombroso and his contemproraries is regarded today as a historical curiosity, not scientific fact. Strict biological determinism is no longer taken seriously (later in his career even Lombroso recognized that not all criminals were biological throwbacks). Early biological determinism has been discredited because it is methodologically flawed: most studies did not use control groups from the general population to compare results, a violation of the scientific method.

^ Beirne, Piers (March 1987). "Adolphe Quetelet and the Origins of Positivist Criminology". American Journal of Sociology. 92 (5): 1140–1169. doi:10.1086/228630.

^ Lochner, Lance (2004). "The American Economic Review". The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self-Reports. 94: 155–189. doi:10.1257/000282804322970751.

^ Hayward, Keith J. (2004). City Limits: Crime, Consumerism and the Urban Experience. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-904385-03-5.

^ Garland, David (2002). "Of Crimes and Criminals". In Maguire, Mike; Rod Morgan; Robert Reiner. The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, 3rd edition. Oxford University Press. p. 21.

^ "Henry Mayhew: London Labour and the London Poor". Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

^ Herman, Nancy (1995). Deviance: A Symbolic Interactionist Approach. Michigan: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 64–68. ISBN 978-1882289387.

^ Anderson, Ferracuti. "Criminological Theory Summaries" (PDF). Cullen & Agnew. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

^ Hester, S., Eglin, P. 1992, A Sociology of Crime, London, Routledge.

^ Shaw, Clifford R.; McKay, Henry D. (1942). Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-75125-2.

^ abc Bursik Jr.; Robert J. (1988). "Social Disorganization and Theories of Crime and Delinquency: Problems and Prospects". Criminology. 26 (4): 519–539. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1988.tb00854.x.

^ Morenoff, Jeffrey; Robert Sampson; Stephen Raudenbush (2001). "Neighborhood Inequality, Collective Efficacy and the Spatial Dynamics of Urban Violence". Criminology. 39 (3): 517–60. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00932.x.

^ Siegel, Larry (2015). Criminology: Theories, Patterns, and Typologies. Cengage Learning. p. 191. ISBN 978-1305446090.

^ Merton, Robert (1957). Social Theory and Social Structure. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-921130-4.

^ Rosenberger, Jared (October 2016). "Television consumption and institutional anomie theory". Television Consumption and Institutional Anomie Theory. 49: 305–325. 21p.

^ Hughes, Lorine (2015). "Economic Dominance, the "American Dream," and Homicide". A Cross-National Test of Institutional Anomie Theory. 85: 100–128.

^ Samantha, Applin (April 2014). "Her American Dream". Bringing Gender into Institutional-Anomie Theory. 10: 36–59. doi:10.1177/1557085114525654.

^ Cohen, Albert (1955). Delinquent Boys. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-905770-4.

^ Kornhauser, R. (1978). Social Sources of Delinquency. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45113-8.

^ ab Cloward, Richard, Lloyd Ohlin (1960). Delinquency and Opportunity. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-905590-8.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Raymond D. Gastil, "Homicide and a Regional Culture of Violence," American Sociological Review 36 (1971): 412-427.

^ Hirschi, Travis (1969). Causes of Delinquency. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0900-1.

^ Gottfredson, Michael R., Hirschi, Travis (1990). A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Wilson, Harriet (1980). "Parental Supervision: A Neglected Aspect of Delinquency". British Journal of Criminology. 20 (3): 203–235. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a047169.

^ ab Freud, Sigmund (2011). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Editions.

^ Rosnick, Phillida (2017). "Mental Pain and Social Trauma". The International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 94 (6): 1200–1202. doi:10.1111/1745-8315.12165. PMID 24372131.

^ ab Gilman, Sander (2008). "Freud and the Making of Psychoanalysis". The Lancet. 372 (9652): 1799–1800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61746-8.

^ Mead, George Herbert (1934). Mind Self and Society. University of Chicago Press.

^ Becker, Howard (1963). Outsiders. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-83635-5.

^ Slattery, Martin (2003). Key Ideas In Sociology. Nelson Thornes. pp. 154+.

^ Kelin, Malcolm (March 1986). "Labeling Theory and Delinquency Policy: An Experimental Test". Criminal Justice & Behaviour. 13 (1): 47–79. doi:10.1177/0093854886013001004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013.

^ Rhodes, Richard (2000). Why They Kill: The Discoveries of a Maverick Criminologist. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-40249-4.

^ Gary Becker, "Crime and Punishment", in Journal of Political Economy, vol. 76 (2), March–April 1968, p.196-217

^ George Stigler, "The Optimum Enforcement of Laws", in Journal of Political Economy, vol.78 (3), May–June 1970, p. 526–536

^ ab Cornish, Derek; Ronald V. Clarke (1986). The Reasoning Criminal. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-96272-6.

^ ab Clarke, Ronald V. (1992). Situational Crime Prevention. Harrow and Heston. ISBN 978-1-881798-68-2.

^ Sutton, M. Schneider, J. and Hetherington, S. (2001) Tackling Theft with the Market Reduction Approach. Crime Reduction Research Series paper 8. Home Office. London. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Sutton, M. (2010) Stolen Goods Markets. U.S. Department of Justice. Centre for Problem Oriented Policing, COPS Office. Guide No 57. "Stolen Goods Markets | Center for Problem-Oriented Policing". Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

^ Home Office Crime Reduction Website. Tackling Burglary: Market Reduction Approach. "Crime prevention - GOV.UK". Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

^ Felson, Marcus (1994). Crime and Everyday Life. Pine Forge. ISBN 978-0-8039-9029-6.

^ ab Cohen, Lawrence; Marcus Felson (1979). "Social Change and Crime Rate Trends". American Sociological Review. 44 (4): 588–608. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.3696. doi:10.2307/2094589. JSTOR 2094589.

^ Eck, John; Julie Wartell (1997). Reducing Crime and Drug Dealing by Improving Place Management: A Randomized Experiment. National Institute of Justice.

^ Kevin M. Beaver and Anthony Walsh. 2011. Biosocial Criminology. Chapter 1 in The Ashgate Research Companion to Biosocial Theories of Crime. 2011. Ashgate.

^ WALTON K. G.; LEVITSKY D. K. (2003). "Effects of the Transcendental Meditation program on neuroendocrine abnormalities associated with aggression and crime". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 36 (1–4): 67–87. doi:10.1300/J076v36n01_04.

^ Sparks, Richard F., "A Critique of Marxist Criminology." Crime and Justice. Vol. 2 (1980). JSTOR. 165.

^ Sparks, Richard F., "A Critique of Marxist Criminology." Crime and Justice. Vol. 2 (1980). JSTOR. 169.

^ Sparks, Richard F., "A Critique of Marxist Criminology." Crime and Justice. Vol. 2 (1980). JSTOR. 170 - 171

^ J. B. Charles, C. W. G. Jasperse, K. A. van Leeuwen-Burow. "Criminology Between the Rule of Law and the Outlaws." (1976). Deventer: Kluwer D.V. 116

^ Richards, Stephen C.; Ross, Jeffrey Ian (2001). "Introducing the New School of Convict Criminology". Social Justice. 28 (1 (83)): 177–190. JSTOR 29768063.

^ Leyva, Martin; Bickel, Christopher (2010). "From Corrections to College: The Value of a Convict's Voice" (PDF). Western Criminology Review. 11 (1): 50–60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017.

^ oucriminology (2016-01-14). "What is Convict criminology?". Harm & Evidence Research Collaborative (HERC). Retrieved 2019-03-11.

^ Ball, Matthew. "Queer Criminology as Activism." Critical Criminology 24.4 (2016): 473-87. Web. 5 April 2018

^ abcdef Hayward, Keith J.; Young, Jock (August 2004). "Cultural Criminology". Theoretical Criminology. 8 (3): 259–273. doi:10.1177/1362480604044608. ISSN 1362-4806.

^ abcd Ferrell, Jeff (1999-08-01). "Cultural criminology". Annual Review of Sociology. 25 (1): 395–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.395. ISSN 0360-0572.

^ abcd Kane, Stephanie C. (August 2004). "The Unconventional Methods of Cultural Criminology". Theoretical Criminology. 8 (3): 303–321. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.203.812. doi:10.1177/1362480604044611. ISSN 1362-4806.

^ ab Naegler & Salman (2016). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". Feminist Criminology. 11 (4): 354–374. doi:10.1177/1557085116660609.

^ "Relative Deprivation definition | Psychology Glossary | alleydog.com". www.alleydog.com. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

^ "Relative Deprivation in Psychology: Theory & Definition - Video & Lesson Transcript". Study.com. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

^ DiSalvo, David. "Whether Rich Or Poor, Feeling Deprived Makes Us Steal More". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

^ Bunei, E. K., & Barasa, B. (2017). “Farm Crime Victimisation in Kenya: A Routine Activity Approach.” International Journal of Rural Criminology, 3(2), 224-249.

^ Stallwitz, A. (2014). “Community-Mindedness: Protection against Crime in the Context of Illicit Drug Cultures?” International Journal of Rural Criminology, 2(2), 166-208.

^ "Attack the System » Crime and Conflict Theory." Attack the System. Ed. Attack the System. American Revolutionary Vanguard, 6 June 2007. Web. 23 February 2012. <"Crime and Conflict Theory". 30 January 2011. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.>.

^ Hillyard, P., Pantazis, C., Tombs, S., & Gordon, D. (2004). Beyond Criminology: Taking Harm Seriously. London: Pluto

^ clear, todd (6 October 2010). "editorial introduction to public criminologies". Criminology and Public Criminologies. 9 (4): 721–724. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2010.00665.x.

^ Barak-Glantz, I.L., E.H. Johnson (1983). Comparative criminology. Sage.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

- Jean-Pierre Bouchard, La criminologie est-elle une discipline à part entière ? / Can criminology be considered as a discipline in its own right ? L'Evolution Psychiatrique 78 (2013) 343-349.

- Wikibooks: Introduction to sociology

Beccaria, Cesare, Dei delitti e delle pene (1763–1764)- Barak, Gregg (ed.). (1998). Integrative criminology (International Library of Criminology, Criminal Justice & Penology.). Aldershot: Ashgate/Dartmouth.

ISBN 1-84014-008-9

Pettit, Philip and Braithwaite, John. Not Just Deserts. A Republican Theory of Criminal Justice

ISBN 978-0-19-824056-3 (see Republican Criminology and Victim Advocacy: Comment for article concerning the book in Law & Society Review, Vol. 28, No. 4 (1995), pp. 765–776)

Simply Criminology - Criminology Articles, Research, Reviews and Library: (see The Online Criminology Resource)

Briar, S., & Piliavin, I. (1966). Delinquency, Situational Inducements, and Commitment to Conformity. Social Problems, 13 (3).

Cohen, A. K. (1965). The Sociology of the Deviant Act: Anomie Theory and Beyond. American Sociological Review, 30.

- Catherine Blatier, "Introduction à la psychocriminologie". Paris : Dunod, 2010.

- Catherine Blatier, "La délinquance des mineurs. Grenoble". Presses Universitaires, 2nd Edition, 2002.

- Catherine Blatier, "The Specialized Jurisdiction: A Better Chance for Minors". International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. (1998), pp. 115–127.

- Jaishankar, K. (2016). Interpersonal Criminology: Revisiting Interpersonal Crimes and Victimization (I ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

ISBN 9781498748599. - Jaishankar, K., & Ronel, N. (2013). Global Criminology: Crime and Victimization in a Globalized Era (I ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

ISBN 9781439892497. - Jaishankar, K. (2011). Cyber Criminology: Exploring Internet Crimes and Criminal Behavior (I ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

ISBN 9781439829493. Retrieved 5 July 2017. - Mathieu Deflem, 1997. "Surveillance and Criminal Statistics: Historical Foundations of Governmentality." pp. 149–184 in Studies in Law, Politics and Society, Volume 17, edited by Austin Sarat and Susan Silbey. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Social Deviance |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Criminology |

Criminology at Curlie