Popular Front of Moldova

The Popular Front of Moldova (Romanian: Frontul Popular din Moldova) was a political movement in the Moldavian SSR, one of the 15 union republics of the former Soviet Union, and in the newly independent Republic of Moldova. Formally, the Front existed from 1989 to 1992. It was the successor to the Democratic Movement of Moldova (Mișcarea Democratică din Moldova; 1988–89), and was succeeded by the Christian Democratic Popular Front (Frontul Popular Creștin Democrat; 1992–99) and ultimately by the Christian-Democratic People's Party (Partidul Popular Creștin Democrat; since 1999).

The Popular Front was well organized nationally, with its strongest support in the capital and in areas of the country most heavily populated by Moldavians. Once the organization was in power, however, internal disputes led to a sharp fall in popular support, and it fragmented into several competing factions by early 1993.[1]

Contents

1 Democratic Movement of Moldova

2 Founding

3 Grand National Assembly

4 Rise to power

5 Decline and transformation

6 Notes

7 References

Democratic Movement of Moldova

Anatol Șalaru

The precursor of the Front, the Democratic Movement of Moldova (Romanian: Mișcarea Democratică din Moldova; 1988–89) organized public meetings, demonstrations, and song festivals since February 1988, which gradually grew in size and intensity. In the streets, the center of public manifestations was the Stephen the Great Monument in Chișinău, and the adjacent park harboring Aleea Clasicilor ( The Alee of the Classics [of the Literature]). On January 15, 1988, in a tribute to Mihai Eminescu at his bust on the Aleea Clasicilor, Anatol Șalaru submitted the proposal to continue the meetings. In the public discourse, the movement called for national awakening, freedom of speech, revival of Moldavian traditions, and for attainment of official status for the Moldovan language and return of it to the Latin script. The transition from "movement" (informal association) to "front" (formal association) was regarded by its sympathizers as a natural "upgrade" once the movement has gained momentum with the public, and the Soviet authorities could no longer crack down on it.

Founding

Leonida Lari was one of the founders and main leaders of Popular Front of Moldova.

The Front's founding congress took place on May 20, 1989 amidst the backdrop of a ferment that had gripped the republic since late 1988,[2] spurred by the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev. Initially, it was a reformist movement modeled on the Baltic pattern[3] that stressed glasnost, perestroika and demokratizatsiya and was not exclusivist. The congress was attended by representatives from many of Moldova's ethnic groups, including a delegate from the Gagauz umbrella organisation, Gagauz Halkı ("The Gagauz People").[4]

During the second congress (30 June - 1 July 1989), Ion Hadârcă was elected as president of the Front, from among 3 candidates for the job. Other two candidates that sought election to the post were Nicolae Costin and Gheorghe Ghimpu.

FPM was at first called a "public organization", since political parties other than the Communist Party were forbidden in the USSR. The movement initially consisted of a broad multi-ethnic coalition of independent cultural and political groups[5] that pressed for reform within the Soviet system and for the national emancipation of ethnic Moldovans.[1]

However, an ethnic cleavage quickly became apparent as titular Popular Front representatives called only for the Moldovan language, written in Latin script, to be made official, and other ethnicities began to feel alienated. Already in April 1989, in response to this agitation, Gagauz nationalists had begun to demand the creation of their own ethno-federal unit in Moldova, and Gagauz mobilization accelerated in the wake of massive Moldovan nationalist demonstrations that summer calling for a new language law, republican sovereignty and secession.[6] Also in summer 1989, Russian-speaking elites in Transnistria had defected from the movement, perceiving the language demands as an example of chauvinism. In early August, a Communist party newspaper in Tiraspol published drafts of the new law, showing that no plans existed to declare Russian a second official language; this led to a wave of strikes in Transnistria initiated by local party cadres and factory bosses.[7][8] An alliance between Gagauz and Russians formed, in opposition to Moldovan demands and enjoying support from the USSR government,[6] so that by early August, Moldova's ad hoc multiethnic opposition, which had allowed the Popular Front to emerge as a unified force from a plethora of informal organisations 2½ months earlier, was completely defunct.[7] Moreover, Moscow was worried by the Front's raising another issue: the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact; it insisted Soviet authorities would have to recognise that Moldova was taken from Romania in 1940 on the basis of a secret deal between Stalin and Hitler, a fact long denied by Soviet officials.[3] Nevertheless, the Popular Front was far from dead and soon achieved its first major objective.

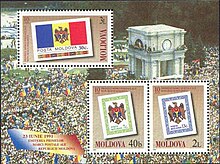

Grand National Assembly

Grand National Assembly (Romanian: Marea Adunare Națională) was the first major achievement of the Popular Front. Mass demonstrations organized by its activists, including one (the "Grand National Assembly") attended by 300,000 participants on August 27,[9] were of critical importance[7] in convincing the Moldovan Supreme Soviet to adopt a new language law on August 31, 1989, to thunderous applause. The law stipulated Latin-script Moldovan (considered identical to Romanian by linguists) as the state language, although it was quite moderate, for instance defining Russian as a second "language of interethnic communication" alongside Moldovan,[10] and the language of communication with the Soviet Union authorities. Later, when this autonomous territorial unit was created, Gagauz and Russian were recognized as official alongside Moldovan in Gagauzia.[6]

On August 27, 1989, the FPM organized a mass demonstration in Chișinău, that became known as the Great National Assembly, which pressured the authorities of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic to adopt a language law on August 31, 1989 that proclaimed the Moldovan language written in the Latin script to be the state language of the MSSR. Its identity with the Romanian language was also established.[11][12] August 31 has been the National Language Day ever since.[13]

Rise to power

Gheorghe Ghimpu at Parliament on April 27, 1990

Gheorghe Ghimpu at a Front meeting (March 7, 1991)

Elections to the Moldovan Supreme Soviet were held in February–March 1990; while the Communist Party was the only one registered for this contest, opposition candidates were allowed to run as individuals.[14] Together with affiliated groups, the Front won a landslide victory[15] and one of its leaders, Mircea Druc, formed the new government. The Popular Front saw its government as a purely transitional ministry; its role was to dissolve the Moldavian SSR and join Romania.[10] Its militancy grew: at a March 1990 rally, the Front adopted a resolution calling the 1918 Union of Bessarabia with Romania "natural and legitimate"; for pan-Romanians such as Iurie Roșca, unification was the proper outcome of democratisation.[16] The Front helped set up a massive demonstration on May 6, the Bridge of Flowers, which saw multitudes gather on both sides as eight crossings on the Prut were opened and people crossed freely between Moldova and Romania.[16] The policies of the Druc government included a virtual purge of non-Moldovans from cultural institutions and the reorientation of educational policy away from Russian-speakers.[17] The nationalists argued that the Popular Front should immediately use its majority in the Supreme Soviet to attain independence from Russian domination, end migration into the republic, and improve the status of ethnic Romanians.[1] At the Front's second congress in June 1990, it declared itself in opposition to the leadership of Mircea Snegur (president of the republic's Supreme Soviet), which it claimed was failing to maintain order in restive regions and was too slow in pulling Moldova out of the USSR. At the congress, the Front's executive board, headed by Roșca, openly called for political union with Romania, and Front statutes were changed so that members could belong to no other political organisation.[18]

However, this strident line, coupled with receptiveness to union in Romania (led by Ion Iliescu after the December 1989 Revolution), caused other Moldovan politicians to become more public in their desire for the continued existence of a separate state. A chief supporter of Moldova's sovereignty was Snegur, who became president in September 1990.[19] Also, in protest and fear of the events of 1990, the now-alienated regions of Gagauzia and Transnistria moved to break away from Moldova,[10] declaring their own independent republics on August 19 and September 2, respectively.

Faced with what they considered a concerted effort by ethnic Romanian nationalists to dominate the republic, hardliners and minority activists banded together and began to resist majority initiatives. Organized in the Supreme Soviet as the Soviet Moldavia (Sovetskaya Moldaviya) faction, the anti-reformers became increasingly inflexible. Yedinstvo and its supporters within the Supreme Soviet argued against independence from the Soviet Union, against implementation of the August 1989 language law, and for increased autonomy for minority areas. Hence, clashes occurred almost immediately once the new Supreme Soviet began its inaugural session in April 1990.[1]

The leaders of the FPM were driven by the core belief that Romanians and Moldovans form a single nation, and should eventually make a single country. Although an explicit unionist position was not adopted until it had been relegated to permanent opposition status, the Front leaders supported a rapid unification with Romania. In addition, some leaders of the PFM were quick to alienate ethnic minorities and PFM sympathizers from within the Soviet system. The discrepancy with the immediate economic needs of the population, and the alienation of many sympathizers stood at the core of the Front's inability to remain in power after 1992.

Decline and transformation

Snegur fired Druc after a "disastrous"[20] tenure on May 28, 1991 and Moldova declared independence three months later. At its third congress in February 1992, the Front transformed itself from a mass movement into a political party, becoming the Christian Democratic Popular Front (FPCD), overtly committed to union with Romania. It also rejected the name "Republic of Moldova" in favour of Bessarabia, seemingly conceding the loss of Transnistria. Once union was revealed as the Front's ultimate aim, a serious loss in numbers and influence followed. A vast network of local groups had allowed it to organise very effectively in 1989. It was able to attract hundreds of thousands to the Grand National Assembly in 1989, but only a few hundred to similar rallies in 1993. Its spiritual leader, the author Ion Druță, became disillusioned and settled in Moscow. Snegur and other former reform Communists, once allied to the Front, moved to consolidate the new state and their position within it.[21]

The president came out as a strong anti-unionist after Moldova's defeat in the June 1992 War of Transnistria; to retain any hope of securing Transnistria, the idea of union with Romania had to be dropped, and so the Front moved into opposition and the anti-unionist Agrarian Democrats[22] formed government.[23] Druc and other members,[24] convinced by 1991-1992 that the goal of union had been lost, settled in Romania. Pan-Romanians themselves split into the FPCD and the more moderate Congress of the Intelligentsia (formed April 1993), which also included former Frontists.[25] By the time of the February 1994 election, in which the FPCD took 7.5% of the vote, the Popular Front tendency had dissipated from the vanguard of Moldovan politics. Its legacy was further undermined three days later, when language testing for state employment, due to begin that April, was canceled; and the following month, when a referendum overwhelmingly affirmed Moldova's sovereignty.[26] No Frontist has held a major ministerial portfolio since the Druc period; moderate pan-Romanists, though they came to eclipse the FPCD in the mid-1990s, had completely disappeared as an organised political force by the February 2001 election.[27] Still, Roșca's PPCD, successor to the Front, continues to be represented by a small parliamentary contingent, and informal but powerful cultural links ensure that the pan-Romanist trend has retained some influence in Moldova.[28]

Notes

^ abcd The 1990 Elections, Fedor, Helen, ed. Moldova: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1995.

^ Beissinger, p.225

^ ab Kolstø, p.139

^ King, p.138

^ Political Parties, Fedor, Helen, ed. Moldova: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1995.

^ abc Beissinger, p.226

^ abc King, p.140

^ The strikes, organised by the United Council of Workers' Collectives or OSTK in Russian, were not purely driven by cultural considerations. OSTK was set up by factory management; these individuals' factories were under direct control from Moscow and risked losing all their influence and power in the event of union with Romania. Kolstø, p.139

^ Esther B. Fein, "Baltic Nationalists Voice Defiance But Say They Won't Be Provoked", in The New York Times, August 28, 1989

^ abc Kolstø, p.140

^ (in Romanian) Horia C. Matei, "State lumii. Enciclopedie de istorie." Meronia, București, 2006, p. 292-294

^ Legea cu privire la functionarea limbilor vorbite pe teritoriul RSS Moldovenesti Nr.3465-XI din 01.09.89 Vestile nr.9/217, 1989 Archived 2011-08-09 at the Wayback Machine. (Law regarding the usage of languages spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova): "Moldavian SSR supports the desire of the Moldovans that live across the borders of the Republic, and considering the existing linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity — of the Romanians that live on the territory of the USSR, of doing their studies and satisfying their cultural needs in their native language."

^ Limba Noastra (end of August) – Language Day

^ Vorkunova in Alker, p.107

^ Open supporters of the Front took about 27% of seats; together with moderate Communists, mainly from rural districts, they commanded a majority. They gained complete control once Gagauz and Transnistrian deputies walked out in protest over Romanian-oriented cultural reforms. King, p.146

^ ab King, p.149

^ King, p.151

^ King, pp.152-3

^ King, p.150

^ Fawn, p.65

^ King, p.153

^ Initially allied with the Front, the Agrarians defected in 1991. Fawn, p.65

^ Kolstø, p.144

^ Among these were culture minister Ion Ungureanu, and the prominent poets Leonida Lari and Grigore Vieru. Fawn, p.65

^ King, p.154

^ Melvin, p.67

^ Fawn, p.66

^ Fawn, p. 66-7

References

Alker, Hayward R.; Gurr, Ted Robert; Rupesinghe, Kumar (eds.). Journeys Through Conflict: Narratives and Lessons. Rowman & Littlefield, 2001, .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 0-7425-1028-X.- Beissinger, Mark R. Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge University Press, 2002,

ISBN 0-521-00148-X. - Fawn, Rick. Ideology and National Identity in Post-communist Foreign Policies. Routledge, 2004,

ISBN 0-7146-8415-5. - King, Charles. The Moldovans. Hoover Press, 2000,

ISBN 0-8179-9792-X. - Kolstø, Pal. Political Construction Sites: Nation-building in Russia and the Post-Soviet States. Westview Press, 2000,

ISBN 0-8133-3752-6. - Melvin, Neil. Russians Beyond Russia: The Politics of National Identity. Continuum International Publishing Group, 1995,

ISBN 1-85567-233-2.