Leonid Andreyev

Leonid Andreyev | |

|---|---|

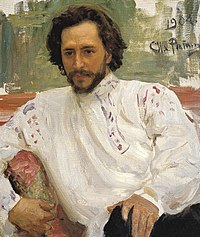

Portrait of Andreyev by Ilya Repin | |

| Born | Leonid Nikolaievich Andreyev (1871-08-21)21 August 1871 Oryol, Oryol Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 12 September 1919(1919-09-12) (aged 48) Mustamäki, Finland |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University (1897) |

| Period | 1890s–1910s |

| Genre | Fiction, Drama |

| Literary movement | Realism • Naturalism • Symbolism • Expressionism |

| Children | Daniil Andreyev, Vadim Andreyev |

| Signature | |

Leonid Nikolaievich Andreyev (Russian: Леони́д Никола́евич Андре́ев, 21 August [O.S. 9 August] 1871 – 12 September 1919) was a Russian playwright, novelist and short-story writer, who is considered to be a father of Expressionism in Russian literature. He is one of the most talented and prolific representatives of the Silver Age period. Andreyev's style combines elements of realist, naturalist, and symbolist schools in literature.

Contents

1 Biography

2 Publication in English

3 Influence

4 Notes

5 Sources

6 External links

Biography

Born in Oryol, Russia within a middle-class family, Andreyev originally studied law in Moscow and in Saint Petersburg. His mother hailed from an old Polish aristocratic, though impoverished, family,[1][2] while he also claimed Ukrainian and Finnish ancestry.[3] He became police-court reporter for a Moscow daily, performing the routine of his humble calling without attracting any particular attention. At this time he wrote poetry and made a few efforts to publish it but was refused by most publishers. In 1898 his first short story, "Bargamot and Garaska" ("Баргамот и Гараська"), was published in the "Kurier" newspaper in Moscow. This story came to the attention of Maxim Gorky who recommended that Andreyev concentrate on his literary work. Andreyev eventually gave up his law practice, fast becoming a literary celebrity, and the two writers remained friends for many years to come. Through Gorky, Andreyev became a member of the Moscow Sreda literary group, and published many of his works in Gorky's Znanie collections.[4]

Andreyev's first collection of short stories and short novels (повести) appeared in 1901, quickly selling a quarter-million copies and making him a literary star in Russia. In 1901 he published "Стена" ("The Wall"), 1902, he published "В тумане" ("In the Fog") and "Бездна" ("The Abyss,") which was a response to "The Kreutzer Sonata" by Leo Tolstoy. These last two stories caused great commotion because of their candid and audacious treatment of sex. In the years between 1898 and 1905 Andreyev published numerous short stories on many subjects, including life in Russian provincial settings, court and prison incidents (where he drew on material from his professional life), and medical settings. His particular interest in psychology and psychiatry gave him an opportunity to explore insights into the human psyche and to depict memorable personalities who later became classic characters of Russian literature ("Thought" 1902).

During the time of the first Russian revolution Andreyev actively participated in the social and political debate as a defender of democratic ideals. Several of his stories, including "The Red Laugh" ("Красный смех", 1904), Governor ("Губернатор", 1905) and The Seven Who Were Hanged ("Рассказ о семи повешенных", 1908) captured the spirit of this period. Starting from 1905 he also produced many theater dramas including The Life of Man (1906), Tsar Hunger (1907), Black Masks (1908), Anathema (1909), and The Days of Our Life (1909).[5]The Life of Man was staged by both Konstantin Stanislavsky (with his Moscow Art Theatre) and Vsevolod Meyerhold (in Saint Petersburg), the two main highlights of Russian theatre of the twentieth century, in 1907.[6]

Andreyev's works of the period after the 1905 revolution often represent the evocation of absolute pessimism and a despairing mood. By the beginning of the second decade of the century he began losing fame as new literary powers such as the Futurists were fast arising.

Aside from his political writings, Andreyev published little after 1914. In 1916, he became the editor of the literary section of the newspaper "Russian Will." He later supported the February Revolution, but foresaw the Bolsheviks' coming to power as catastrophic. In 1917, he moved to Finland. From his house in Finland he addressed manifestos to the world at large against the excesses of the Bolsheviks. Idealist and rebel, Andreyev spent his last years in bitter poverty, and his premature death from heart failure may have been hastened by his anguish over the results of the Bolshevik Revolution. His last novel, Satan's Diary, was left unfinished at the time of his death.

A play, The Sorrows of Belgium, was written at the beginning of the War to celebrate the heroism of the Belgians against the invading German army. It was produced in the United States, as were the plays, The Life of Man (1917), The Rape of the Sabine Women (1922), He Who Gets Slapped (1922), and Anathema (1923). A popular and acclaimed film version of He Who Gets Slapped was produced by MGM Studios in 1924. Some of his works were translated into English by Thomas Seltzer.

Poor Murderer, an adaptation of his short story Thought made by Pavel Kohout, opened on Broadway in 1976.

Leonid Andreyev and his second wife, Anna

He was married to Alexandra Veligorskaia, a niece of Taras Shevchenko. She died of puerperal fever in 1906. They had two sons, Daniil Andreyev, a poet and mystic, author of Roza Mira, and Vadim Andreyev. In 1908 Leonid Andreyev married Anna Denisevich, and decided to separate his two little boys, keeping the elder son, Vadim, with him and sending Daniil to live with Aleksandra's sister. Vadim Andreyev became a poet. He lived in Paris.

Publication in English

During the 1914-1929 period America was avid for anything relating to Edgar Allan Poe and, as Poe's Russian equivalent, translations of Andreyev's work found a ready audience in the English-speaking world. His work was extensively translated in book form, for instance as The Crushed Flower, and other stories (1916); The Little Angel, and other stories (1916); When The King Loses His Head, and other stories (1920). His stories were also published in translation in Weird Tales magazine in the 1920s, such as "Lazarus" in the March 1927 edition.

Leonid Andreyev's granddaughter, daughter of Vadim Andreyev, the American writer and poet Olga Andrejew Carlisle (born 1931), published a collection of his short stories, Visions, in 1987.

Influence

Often referred to as 'a Russian Edgar Allan Poe', Andreyev had an influence through translations on two of the great horror writers, H.P. Lovecraft and R.E. Howard. Copies of his The Seven Who Were Hanged and The Red Laugh were found in the library of horror writer H. P. Lovecraft at his death, as listed in the "Lovecraft's Library" catalogue by S.T. Joshi. Andreyev was also one of the seven "most powerful" writers of all time, in the opinion of Robert E. Howard.[7]

Notes

^ James B. Woodward, Leonid Andreyev: a study, Clarendon P. (1969), p. 3

^ Leo Hamalian & Vera Von Wiren-Garczynski, Seven Russian Short Novel Masterpieces, Popular Library (1967), p. 381

^ Frederick H. White, Degeneration, Decadence and Disease in the Russian fin de siècle: Neurasthenia in the life and work of Leonid Andreev, Oxford University Press (2015), p. 47

^ A Writer Remembers by Nikolay Teleshov, Hutchinson, NY, 1943.

^ Banham (1998, 24)

^ Benedetti (1999, 176–177), Banham (1998, 24), and Carnicke (2000, 34).

^ Robert E. Howard, letter to Tevis Clyde Smith, circa February 20, 1928. Given in: Burke, Rusty (1998), "The Robert E. Howard Bookshelf", The Robert E. Howard United Press Association.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Colby, F.; Williams, T., eds. (1914). "Andréev, Leonid Nikolaevitch". New International Encyclopedia. 1 (2 ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 625..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Colby, F.; Williams, T., eds. (1914). "Andréev, Leonid Nikolaevitch". New International Encyclopedia. 1 (2 ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 625..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 0-521-43437-8. - Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen.

ISBN 0-413-52520-1. - Carnicke, Sharon M. 2000. "Stanislavsky's System: Pathways for the Actor". In Twentieth Century Actor Training. Ed. Alison Hodge. London and New York: Routledge.

ISBN 0-415-19452-0. p. 11–36. - "Leonid Nikolayevich Andreyev." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 06 Oct. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/24016/Leonid-Nikolayevich-Andreyev>.

Imperial Moscow University: 1755-1917: encyclopedic dictionary. Moscow: Russian political encyclopedia (ROSSPEN). A. Andreev, D. Tsygankov. 2010. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-5-8243-1429-8.

External links

Works by Leonid Andreyev at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Leonid Andreyev at Internet Archive

Works by Leonid Nikolayevich Andreyev at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Leonid Andreyev on IMDb

Leonid Andreyev at the Internet Broadway Database- Leonid Andreyev's tombstone

- University of Leeds archive page on Leonid's elder son, Vadim Leonidovich Andreyev

Leonid Andreyev at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Leonid Andreyev at Library of Congress Authorities, with 151 catalogue records