Gujarat Sultanate

Sultanate of Gujarat ગુજરાત સલ્તનત (Gujarati) سلطنت گجرات (Persian) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1407–1573 | |||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||

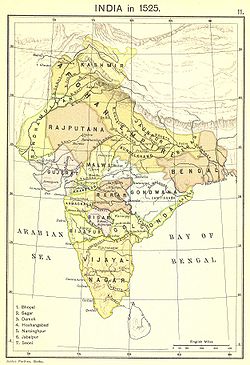

Gujarat Sultanate in 1525 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Anhilwad Patan (1407–1411) Ahmedabad (1411–1484, 1535–1573) Muhammadabad (1484–1535) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Gujarati Persian (official) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Islam Jainism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Muzaffarid dynasty | |||||||||||||

• 1407–1411 | Muzaffar Shah I (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1561-1573, 1584 | Muzaffar Shah III (last) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Declared independence from Delhi Sultanate by Muzaffar Shah I | 1407 | ||||||||||||

• Annexed by Akbar | 1573 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Gujarat, Daman and Diu and Mumbai in | ||||||||||||

Gujarat Sultanate Muzaffarid dynasty (1407–1573) | |

Gujarat under Delhi Sultanate | (1298–1407) |

Muzaffar Shah I | (1391-1403) |

Muhammad Shah I | (1403-1404) |

Muzaffar Shah I | (1404-1411) (2nd reign) |

Ahmad Shah I | (1411-1442) |

Muhammad Shah II | (1442-1451) |

Ahmad Shah II | (1451-1458) |

Daud Shah | (1458) |

Mahmud Begada | (1458-1511) |

Muzaffar Shah II | (1511-1526) |

Sikandar Shah | (1526) |

Mahmud Shah II | (1526) |

Bahadur Shah | (1526-1535) |

Mughal Empire under Humayun | (1535-1536) |

Bahadur Shah | (1536-1537) (2nd reign) |

| Miran Muhammad Shah I (Farooqi dynasty) | (1537) |

Mahmud Shah III | (1537-1554) |

Ahmad Shah III | (1554-1561) |

Muzaffar Shah III | (1561-1573) |

Mughal Empire under Akbar | (1573-1584) |

Muzaffar Shah III | (1584) (2nd reign) |

Mughal Empire under Akbar | (1584-1605) |

Death of Bahadur Shah of Gujarat an Ottoman ally at Diu, in front of the Portuguese, in 1537; (Illustration from the Akbarnama, end of 16th century).

| History of Gujarat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Stone Age .mw-parser-output .noboldfont-weight:normal (Before 4000 BCE)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chalcolithic to Bronze Age (4000–1300 BCE)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Iron Age (1500–300 BCE)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classical Period (380 BCE–1299 CE)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medieval and Early Modern Periods (1299–1819)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Colonial period (1819–1961)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Post-independence (1947–)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Gujarat Sultanate was a medieval India Islamic kingdom established in the early 15th century in present-day Gujarat, India. The founder of the ruling Muzaffarid dynasty, Zafar Khan (later Muzaffar Shah I) was appointed as governor of Gujarat by Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad bin Tughluq IV in 1391, the ruler of the principal state in north India at the time, the Delhi Sultanate. Zafar Khan's father Sadharan, was a Tanka Rajput convert to Islam.[1][2] Zafar Khan defeated Farhat-ul-Mulk near Anhilwada Patan and made the city his capital. Following Timur's invasion of Delhi, the Delhi Sultanate weakened considerably so he declared himself independent in 1407 and formally established Gujarat Sultanate. The next sultan, his grandson Ahmad Shah I founded the new capital Ahmedabad in 1411. His successor Muhammad Shah II subdued most of the Rajput chieftains. The prosperity of the sultanate reached its zenith during the rule of Mahmud Begada. He subdued most of the Rajput chieftains and built navy off the coast of Diu. In 1509, the Portuguese wrested Diu from Gujarat sultanate following the battle of Diu. The decline of the Sultanate started with the assassination of Sikandar Shah in 1526. Mughal emperor Humayun attacked Gujarat in 1535 and briefly occupied it. Thereafter Bahadur Shah was killed by the Portuguese while making a deal in 1537. The end of the sultanate came in 1573, when Akbar annexed Gujarat in his empire. The last ruler Muzaffar Shah III was taken prisoner to Agra. In 1583, he escaped from the prison and with the help of the nobles succeeded to regain the throne for a short period before being defeated by Akbar's general Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana.[3]

Contents

1 Origin

2 History

2.1 Early rulers

2.2 Ahmad Shah I

2.3 Successors of Ahmad Shah I

2.4 Mahmud Begada

2.5 Muzaffar Shah II and his successors

2.6 Bahadur Shah and his successors

2.7 Muzaffar Shah III

3 List of rulers

4 Administration

5 Sources of history

6 Architecture

7 References

7.1 Bibliography

8 External links

Origin

During the rule of Muhammad bin Tughluq, his cousin Firuz Shah Tughlaq was once on a hunting expedition in area what is now Kheda district of Gujarat. He lost his way and lost. He reached village Thasra. He was welcome to partake in hospitality by village headmen, two brothers of Tanka Rajput family, Sadhu and Sadharan. After drinking, he revealed his identity as a cousin and successor of the king. The brothers offered his beautiful sister in marriage and he accepted. They accompanied Firuz Shah Tughluq to Delhi along with his sister. They converted to Islam there. Sadhu assumed new name, Samsher Khan while Sadharan assumed Wajih-ul-Mulk. They were disciples of Saint Hazrat-Makhdum-Sayyid-i-Jahaniyan-Jahangshi aka Saiyyd Jalaluddin Bukhari.[1][2][4][5]

History

Early rulers

Delhi Sultan Firuz Shah Tughluq appointed Malik Mufarrah, also known as Farhat-ul-Mulk and Rasti Khan governor of Gujarat in 1377. In 1387, Sikandar Khan was sent to replace him, but he was defeated and killed by Farhat-ul-Mulk. In 1391, Sultan Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad bin Tughluq appointed Zafar Khan, the son of Wajih-ul-Mulk as governor of Gujarat and conferred him the title of Muzaffar Khan (r. 1391 - 1403, 1404 - 1411). In 1392, he defeated Farhat-ul-Mulk in the battle of Kamboi, near Anhilwada Patan and occupied the city of Anhilwada Patan.[6][7][5]

In 1403, Zafar Khan's son Tatar Khan urged his father to march on Delhi, which he declined. As a result, in 1408, Tatar imprisoned him in Ashawal (future Ahmedabad) and declared himself sultan under the title of Muhammad Shah I (r. 1403 - 1404). He marched towards Delhi, but on the way he was poisoned by his uncle, Shams Khan. After the death of Muhammad Shah, Muzaffar was released from the prison and he took over the control over administration. In 1407, he declared himself as Sultan Muzaffar Shah I, took the insignia of royalty and issued coins in his name. After his death in 1411, he was succeeded by his grandson, the son of Tatar Khan, Ahmad Shah I.[8][6][5]

Ahmad Shah I

Soon after his accession, Ahmad Shah I was faced with a rebellion of his uncles. The rebellion was led by his eldest uncle Firuz Khan, who declared himself king. Ultimately Firuz and his brothers surrendered to him. During this rebellion Sultan Hushang Shah of Malwa Sultanate invaded Gujarat. He was repelled this time but he invaded again in 1417 along with Nasir Khan, the Farooqi dynasty ruler of Khandesh and occupied Sultanpur and Nandurbar. Gujarat army defeated them and later Ahmad Shah led four expeditions into Malwa in 1419, 1420, 1422 and 1438.[9][5]

In 1429, Kanha Raja of Jhalawad with the help of the Bahmani Sultan Ahmad Shah ravaged Nandurbar. But Ahmad Shah's army defeated the Bahmani army and they fled to Daulatabad. The Bahmani Sultan Ahmad Shah sent strong reinforcements and the Khandesh army also joined them. They were again defeated by the Gujarat army. Finally, Ahmad Shah annexed Thana and Mahim from Bahmani Sultanate.[9][5]

At the beginning of his reign, he founded the city of Ahmedabad which he styled as Shahr-i-Mu'azzam (the great city) on the banks of Sabarmati River. He shifted the capital from Anhilwada Patan to Ahmedabad. The Jami Masjid (1423) in Ahmedabad were built during his reign.[10] Sultan Ahmad Shah died in 1443 and succeeded by his eldest son Muhammad Shah II.[9][5]

Successors of Ahmad Shah I

Muhammad Shah II (r. 1442 - 1451) first led a campaign against Idar and forced its ruler, Raja Hari Rai or Bir Rai to submit to his authority. He then exacted tribute from the Rawal of Dungarpur. In 1449, he marched against Champaner, but the ruler of Champaner, Raja Kanak Das, with the help of Malwa Sultan Mahmud Khilji forced him to retreat. On the return journey, he fell seriously ill and died in February, 1451. After his death, he was succeeded by his son Qutb-ud-Din Ahmad Shah II (r. 1451 - 1458).[11] Ahmad Shah II defeated Khilji at Kapadvanj. He helped Firuz Khan ruling from Nagaur against Rana Kumbha of Chittor's attempt to overthrow him. After death of Ahmad Shah II in 1458, the nobles raised his uncle Daud Khan, son of Ahmad Shah I, to the throne.[5]

Mahmud Begada

But within a short period of seven or twenty-seven days, the nobles deposed Daud Khan and set on the throne Fath Khan, son of Muhammad Shah II. Fath Khan, on his accession, adopted the title Abu-al Fath Mahmud Shah, popularly known as Mahmud Begada. He expanded the kingdom in all directions. He received the sobriquet Begada, which literally means the conqueror of two forts, probably after conquering Girnar and Champaner forts. Mahmud died on 23 November 1511.[12][5]

Muzaffar Shah II and his successors

Khalil Khan, son of Mahmud Begada succeeded his father with the title Muzaffar Shah II. In 1519, Rana Sanga of Chittor defeated a joint army of Malwa and Gujarat sultanates and took Mahmud Shah II of Malwa captive. Muzaffar Shah sent an army to Malwa but their service was not required as Rana Sanga had generously restored Mahmud Shah II to the throne. Rana Sanga later invaded Gujarat and plundered the Sultanate's treasuries, greatly damaging its prestige.[13] He died on 5 April 1526 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Sikandar.[14][5]

After few months, Sikandar Sháh was murdered by a noble Imád-ul-Mulk, who seated a younger brother of Sikandar, named Násir Khán, on the throne with the title of Mahmúd Shah II and governed on his behalf. Other son of Muzaffar Shah II, Bhadur Khan returned from outside of Gujarat and the nobles joined him. Bahádur marched at once on Chámpáner, captured and executed Imád-ul-Mulk and poisoning Násir Khán ascended the throne in 1527 with the title of Bahádur Sháh.[5]

Bahadur Shah and his successors

Bahadur Shah expanded his kingdom and made expeditions to help neighbouring kingdoms. In 1532, Gujarat came under attack of the Mughal Emperor Humayun and fell. Bahadur Shah regained the kingdom in 1536 but he was killed by the Portuguese on board the ship when making a deal with them.[5][15]

Bahadur had no son, hence there was some uncertainty regarding succession after his death. Muhammad Zaman Mirza, the fugitive Mughal prince made his claim on the ground that Bahadur's mother adopted him as her son. The nobles selected Bahadur's nephew Miran Muhammad Shah of Khandesh as his successor, but he died on his way to Gujarat. Finally, the nobles selected Mahmud Khan, the son of Bahadur's brother Latif Khan as his successor and he ascended to the throne as Mahmud Shah III in 1538.[16] Mahmud Shah III had to battle with his nobles who were interested in independence. He was killed in 1554 by his servant. Ahmad Shah III succeed him but now the reigns of the state were controlled by the nobles who divided the kingdom between themselves. He was assassinated in 1561. He was succeed by Muzaffar Shah III.[5]

Muzaffar Shah III

Mughal Emperor Akbar annexed Gujarat in his empire in 1573 and Gujarat became a Mughal Subah (province). Muzaffar Shah III was taken prisoner to Agra. In 1583, he escaped from the prison and with the help of the nobles succeeded to regain the throne for a short period before being defeated by Akbar's general Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana in January 1584.[3] He fled and finally took asylum under Jam Sataji of Nawanagar State. The Battle of Bhuchar Mori was fought between the Mughal forces led by Mirza Aziz Koka and the combined Kathiawar forces in 1591 to protect him. He finally committed suicide when he was surrendered to the Mughal.[5]

List of rulers

Administration

Gujarát was divided politically into two main parts; one, called the khálsah or crown domain administered directly by the central authority; the other, on payment of tribute in service or in money, left under the control of its former rulers. The amount of tribute paid by the different chiefs depended, not on the value of their territory, but on the terms granted to them when they agreed to become feudatories of the king. This tribute was occasionally collected by military expeditions headed by the king in person and called mulkgíri or country-seizing circuits.[5]

The internal management of the feudatory states was unaffected by their payment of tribute. Justice was administered and the revenue collected in the same way as under the Chaulukya kings. The revenue consisted, as before, of a share of the crops received in kind, supplemented by the levy of special cesses, trade, and transit dues. The chief's share of the crops differed according to the locality; it rarely exceeded one-third of the produce, it rarely fell short of one-sixth. From some parts the chief's share was realised directly from the cultivator by agents called mantris; from other parts the collection was through superior landowners.[5]

- Districts and crown lands

The Áhmedábád kings divided the portion of their territory which was under their direct authority into districts or sarkárs. These districts were administered in one of two ways. They were either assigned to nobles in support of a contingent of troops, or they were set apart as crown domains and managed by paid officers. The officers placed in charge of districts set apart as crown domains were called muktiă. Their chief duties were to preserve the peace and to collect the revenue. For the maintenance of order, a body of soldiers from the army headquarters at Áhmedábád was detached for service in each of these divisions, and placed under the command of the district governor. At the same time, in addition to the presence of this detachment of regular troops, every district contained certain fortified outposts called thánás, varying in number according to the character of the country and the temper of the people. These posts were in charge of officers called thánadárs subordinate to the district governor. They were garrisoned by bodies of local soldiery, for whose maintenance, in addition to money payments, a small assignment of land was set apart in the neighbourhood of the post. On the arrival of the tribute-collecting army the governors of the districts through which it passed were expected to join the main body with their local contingents. At other times the district governors had little control over the feudatory chiefs in the neighbourhood of their charge.[5] The Gujarat Sultanate had comprised twenty-five sarkars (administrative units).[17]

- Fiscal

For fiscal purposes each district or sarkár was distributed among a certain number of sub-divisions or parganáhs, each under a paid official styled ámil or tahsildár. These sub-divisional officers realised the state demand, nominally one-half of the produce, by the help of the headmen of the villages under their charge. In the sharehold and simple villages of North Gujarát these village headmen were styled Patels or according to Muslim writers mukaddams and in the simple villages of the south they were known as Desais. They arranged for the final distribution of the total demand in joint villages among the shareholders, and in simple villages from the individual cultivators. The sub-divisional officer presented a statement of the accounts of the villages in his sub-division to the district officer, whose record of the revenue of his whole district was in turn forwarded to the head revenue officer at court. As a check on the internal management of his charge, and especially to help him in the work of collecting the revenue, with each district governor was associated an accountant. Further that each of these officers might be the greater check on the other, Ahmad Shah I enforced the rule that when the governor was chosen from among the royal slaves the accountant should be a free man, and that when the accountant was a slave the district governor should be chosen from some other class. This practise was maintained till the end of the reign of Muzaffar Sháh II, when, according to the Mirăt-i-Áhmedi, the army became much increased, and the ministers, condensing the details of revenue, farmed it on contract, so that many parts formerly yielding one rupee now produced ten, and many others seven eight or nine, and in no place was there a less increase than from ten to twenty per cent. Many other changes occurred at the same time, and the spirit of innovation creeping into the administration the wholesome system of checking the accounts was given up and mutiny and confusion spread over Gujarát.[5]

Sources of history

Mirat-i-Sikandari is a Persian work on the complete history of Gujarat Sultanate written by Sikandar, son of Muhammad aka Manjhu, son of Akbar who wrote it soon after Akbar conquered Gujarat. He had consulted earlier works of history and the people of authority. Other Persian works of the history of Gujarat Sultanate are Tarikh-i-Muzaffar Shahi about reign of Muzaffar Shah I, Tarik-i-Ahmad Shah in verse by Hulvi Shirazi, Tarikh-i-Mahmud Shahi, Tabaqat-i-Mahmud Shahi, Maathi-i-Mahmud Shahi about Mahmud I, Tarikh-i-Muzaffar Shahi about Muzaffar Shah II's conquest of Mandu, Tarikh-i-Bahadur Shahi aka Tabaqat-i-Husam Khani, Tarikh-i-Gujarat by Abu Turab Vali, Mirat-i-Ahmadi. Other important work in Arabic about history of Gujarat includes Zafarul-Walih bi Muzaffar wa Alih by Hajji Dabir.[18]

Architecture

During the Muzaffarid rule, Ahmedabad grew to become one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the world,[citation needed] and the sultans were patrons of a distinctive architecture that blended Islamic elements with Gujarat's indigenous Hindu and Jain architectural traditions. Gujarat's Islamic architecture presages many of the architectural elements later found in Mughal architecture, including ornate mihrabs and minarets, jali (perforated screens carved in stone), and chattris (pavilions topped with cupolas).

References

^ ab Rajput, Eva Ulian, pg. 180

^ ab The Rajputs of Saurashtra, Virbhadra Singhji, pg. 45

^ ab Sudipta Mitra (2005). Gir Forest and the Saga of the Asiatic Lion. Indus Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7387-183-2..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Taylor 1902, pp. 2.

^ abcdefghijklmnopq James Macnabb Campbell, ed. (1896). "MUSALMÁN GUJARÁT. (A.D. 1297–1760): INTRODUCTION) and II. ÁHMEDÁBÁD KINGS. (A. D. 1403–1573.". History of Gujarát. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Volume I. Part II. The Government Central Press. pp. 210–212, 236–270. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

^ ab Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 155-7

^ Taylor 1902, pp. 4.

^ Taylor 1902, pp. 6.

^ abc Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 157-60

^ Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 709-23

^ Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 160-1

^ Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 162-7

^ Bayley's Gujarat, p. 264.

^ Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 167-9

^ "The Cambridge History of the British Empire". CUP Archive. 26 July 2017 – via Google Books.

^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan,

ISBN 81-7276-407-1, pp.391-8

^ A., Nadri, Ghulam (2009). Eighteenth-century Gujarat : the dynamics of its political economy, 1750-1800. Leiden: Brill. p. 10. ISBN 9789004172029. OCLC 568402132.

^ Desai, Z. A. (March 1961). "Mirat-i-Sikandari as a Source for the Study of Cultural and Social Condition of Gujarat under the Sultanate (1403-1572)". In Sandesara, B. J. Journal Of Oriental Institute Baroda Vol.10. X. Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. pp. 235–240.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Taylor, Georg P. (1902). The Coins Of The Gujarat Saltanat. XXI. Mumbai: Royal Asiatic Society of Bombay. hdl:2015/104269. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Parikh, Rasiklal Chhotalal; Shastri, Hariprasad Gangashankar, eds. (1977). ગુજરાતનો રાજકીય અને સાંસ્કૃતિક ઇતિહાસ: સલ્તનત કાલ [Political and Cultural History of Gujarat: Sultanate Era]. Research Series - Book No. 71 (in Gujarati). V. Ahmedabad: Bholabhai Jeshingbhai Institute of Learning and Research. pp. 50–136.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gujarat Sultanate |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gujarat Sultanate. |

- Coins of the Gujarat Sultanate