Widow

Relationships (Outline) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Types

| |||||||||

Activities

| |||||||||

Endings

| |||||||||

Emotions and feelings

| |||||||||

Practices

| |||||||||

Abuse

| |||||||||

A widow is a woman whose spouse has died and a widower is a man whose spouse has died. The treatment of widows and widowers around the world varies.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 Economic position

2.1 Effects of widowhood

3 Superstitious beliefs against widows

4 Classic and contemporary social customs

4.1 Widow inheritence

4.2 Hinduism

4.3 Joseon Korea

5 See also

6 References

Terminology

A widow is a woman whose spouse has died, while a widower is a man whose spouse has died. The state of having lost one's spouse to death is termed widowhood.[1] These terms are not applied to a divorcé(e) following the death of an ex-spouse.[citation needed]

The term widowhood can be used for either sex, at least according to some dictionaries,[2][3] but the word widowerhood is also listed in some dictionaries.[4][5] Occasionally, the word viduity is used.[citation needed] The adjective for either sex is widowed.[6][7]

Economic position

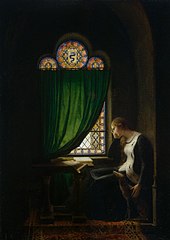

Valentine of Milan Mourning Her Husband, the Duke of Orléans, by Fleury-François Richard

Statue of a mother at Yasukuni Shrine, dedicated to war widows who raised their children alone.

Widows of Uganda supporting each other by working on crafts in order to sell them and make an income

In societies where the husband is the sole provider, his death can leave his family destitute. The tendency for women generally to outlive men can compound this, as can men in many societies marrying women younger than themselves. In some patriarchal societies, widows may maintain economic independence. A woman would carry on her spouse's business and be accorded certain rights, such as entering guilds. More recently, widows of political figures have been among the first women elected to high office in many countries, such as Corazón Aquino or Isabel Martínez de Perón.

In 19th-century Britain, widows had greater opportunity for social mobility than in many other societies. Along with the ability to ascend socio-economically, widows—who were "presumably celibate"—were much more able (and likely) to challenge conventional sexual behaviour than married women in their society.[8]

In some parts of Europe, including Russia, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Italy and Spain, widows used to wear black for the rest of their lives to signify their mourning, a practice that has since died out. Many immigrants from these cultures to the United States as recently as the 1970s have loosened this strict standard of dress to only two years of black garments[citation needed]. However, Orthodox Christian immigrants may wear lifelong black in the United States to signify their widowhood and devotion to their deceased husband.

In other cultures, however, widowhood customs are stricter. Often, women are required to remarry within the family of their late husband after a period of mourning.[citation needed] With the rise of HIV/AIDS levels of infection across the globe, rituals to which women are subjected in order to be "cleansed" or accepted into her new husband's home make her susceptible to the psychological adversities that may be involved as well as imposing health risks.[citation needed]

It may be necessary for a woman to comply with the social customs of her area because her fiscal stature depends on it, but this custom is also often abused by others as a way to keep money within the deceased spouse's family.[9] It is also uncommon for widows to challenge their treatment because they are often "unaware of their rights under the modern law…because of their low status, and lack of education or legal representation."[10] . Unequal benefits and treatment[clarification needed] generally received by widows compared to those received by widowers globally[example needed] has spurred an interest in the issue by human rights activists.[10]

As of 2004, women in United States who were "widowed at younger ages are at greatest risk for economic hardship." Similarly, married women who are in a financially unstable household are more likely to become widows "because of the strong relationship between mortality [of the male head] and wealth [of the household]."[9] In underdeveloped and developing areas of the world, conditions for widows continue to be much more severe. However, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women ("now ratified by 135 countries"), while slow, is working on proposals which will make certain types of discrimination and treatment of widows (such as violence and withholding property rights) illegal in the countries that have joined CEDAW.[10]

Effects of widowhood

The phenomenon that refers to the increased mortality rate after the death of a spouse is called the widowhood effect.[citation needed]. It is “strongest during the first three months after a spouse's death, when they had a 66-percent increased chance of dying.”[11] Most widows and widowers suffer from this effect during the first 3 months of their spouse's death, however they can also suffer from this effect later on in their life for much longer than 3 months.[citation needed] There remains controversy over whether women or men have worse effects from becoming widowed, and studies have attempted to make their case for which side is worse off, while other studies try to show that there are no true differences based on gender and other factors are responsible for any differences.[12]

A variable that is deemed important and relative to the effects of widowhood is the gender of the widow. Research has shown that the difference falls in the burden of care, expectations, and finally how the react after the spouse's death. For example, women carry more a burden than men and are less willing to want to go through this again.[13] After being widowed, however, men and women can react very differently and frequently have a change in lifestyle. A study has sought to show that women are more likely to yearn for their late husband if he were to be taken away suddenly. Men on the other hand tend to be more likely to long for their late wife if she were to die after suffering a long, terminal illness.[14]

Another change that happens to most men is that their lifestyle habits become worse. For example, without a wife there, he is probably more likely to not watch what he eats like he would if she were there. Instead of having to make something himself, it is more of a convenience just to order take-out. Women do have a change in lifestyle, but they typically don’t have the problem of eating foods that are bad for her. Instead, women are typically more known to lose weight due to lack of eating. This is likely to be caused as a side effect of depression.[15]

The older spouses grow, the more aware they are of being alone due to the death of their husband or wife. This negatively impacts the mental as well as physical well being in both men and women (Utz, Reidy, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2004 as Cited in Mumtaz 71).

Superstitious beliefs against widows

In parts of Africa, such as in Kenya, widows are viewed as impure and need to be 'cleansed'. This often requires having sex with someone. Those refusing to be cleansed risk getting beaten by superstitious villagers, who may also harm the woman's children. It is argued that this notion arose from the idea that if a husband dies, the woman may have performed witchcraft against him.

In parts of India and Nepal a woman is often accused of causing her husband’s death and is not allowed to look at another person as her gaze is considered bad luck.[16]

Those likely to be accused and killed as witches, such as in Papua New Guinea, are often widows.[17]

Classic and contemporary social customs

Widow inheritence

Widow inheritance (also known as bride inheritance) is a cultural and social practice whereby a widow is required to marry a male relative of her late husband, often his brother.

Hinduism

Until the early 19th century it was considered honourable in some parts of India for a Hindu widow to immolate herself on her late husband's funeral pyre. This custom, called sati, was outlawed in 1827 in British India and again in 1987 in independent India by the Sati Prevention Act, which made it illegal to support, glorify or attempt to commit sati. Support of sati, including coercing or forcing someone to commit sati, can be punished by death sentence or life imprisonment, while glorifying sati is punishable with one to seven years in prison.

Even if they did not commit suicide, Hindu widows were traditionally prohibited from remarrying. The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856, enacted in response to the campaign of the reformer Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar,[18] legalized widow remarriage and provided legal safeguards against loss of certain forms of inheritance for remarrying a Hindu widow,[19] though, under the Act, the widow forsook any inheritance due her from her deceased husband.[20]

The status of widowhood for Hindus was accompanied by a body symbolism:[21]

- The widow's head was shaved as part of her mourning.

- She could no longer wear a red dot (sindur) on her forehead and was forbidden to wear wedding jewellery.

- She was expected to walk barefoot.

But now, these customs are disappearing.

Joseon Korea

Social stigma in Joseon Korea required that widows remain unmarried after their husbands death. In 1477, Seongjong of Joseon enacted the Widow Remarriage Law, which strengthened pre-exisiting social constraints by barring the sons of widows who remarried from holding public office.[22] In 1489, Seongjong condemned a woman of the royal clan, Yi Guji, when it was discovered that she had cohabited with her slave after being widowed. More than 40 members of her household were arrested and her lover was tortured to death.[23]

See also

- Estate planning

- Orphan

- Remarriage

- Single parent

- Sati

- Widow conservation

References

^ "Definition of WIDOWHOOD". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2016-03-18..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Widowhood definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

^ "widowhood - definition of widowhood in English - Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

^ "Widowerhood definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

^ "Definition of WIDOWERHOOD". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

^ "Widowed definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

^ "widowed Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

^ Behrendt, Stephen C. "Women without Men: Barbara Hofland and the Economics of Widowhood." Eighteenth Century Fiction 17.3 (2005): 481-508. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 14 Sept. 2010.

^ ab "Imagine...." Widows' Rights International. Web. 14 Sep 2010. <http://www.widowsrights.org/index.htm>.

^ abc Owen, Margaret. A World of Widows. Illustrated. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Zed Books, 1996. 181-183. eBook.

^ "'Widowhood effect' strongest during first three months". 14 November 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2017 – via Reuters.

^ Trivedi, J., Sareen, H., & Dhyani, M. (2009). Psychological Aspects of

Widowhood and Divorce. Mens Sana Monogr Mens Sana Monographs, 7(1), 37. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.40648

^ "Gale - Enter Product Login". go.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

^ Wilcox, Sara; Evenson, Kelly R.; Aragaki, Aaron; Wassertheil-Smoller, Sylvia; Mouton, Charles P.; Loevinger, Barbara Lee (2003). "The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative". Health Psychology. 22 (5): 513. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. PMID 14570535.

^ Wilcox, Sara; Evenson, Kelly R.; Aragaki, Aaron; Wassertheil-Smoller, Sylvia; Mouton, Charles P.; Loevinger, Barbara Lee (2003). "The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative". Health Psychology. 22 (5): 513. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. PMID 14570535.

^ "These Kenyan widows are fighting against sexual 'cleansing'". pri.org. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

^ "The gruesome fate of "witches" in Papua New Guinea". economist.com. 13 July 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

^ Forbes 1999, p. 23

^ Peers 2006, pp. 52–53

^ Carroll 2008, p. 80

^ Olson, Carl. The Many Colors of Hinduism. Rutgers University Press.

^ Uhn, Cho. "The Invention of Chaste Motherhood: A Feminist Reading of the Remarriage Ban in the Chosun Era". Asian Journal of Women's Studies. 5 (3). pp. 45–63. doi:10.1080/12259276.1999.11665854.

^ 성종실록 (成宗實錄) [Veritable Records of Seongjong] (in Chinese). 226. 1499.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Widows. |

| Look up widow in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |