Constructivism (art)

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (May 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Zuev Workers' Club, 1927-1929.

Constructivism was an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia beginning in 1913 by Vladimir Tatlin. This was a rejection of the idea of autonomous art. He wanted 'to construct' art. The movement was in favour of art as a practice for social purposes. Constructivism had a great effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. Its influence was widespread, with major effects upon architecture, sculpture, graphic design, industrial design, theatre, film, dance, fashion and to some extent music.

Contents

1 Beginnings

2 Art in the service of the Revolution

3 Tatlin, 'Construction Art' and Productivism

4 Constructivism and consumerism

5 LEF and Constructivist cinema

6 Photography and photomontage

7 Constructivist graphic design

8 Constructivist architecture

9 Legacy

10 Artists closely associated with Constructivism

11 See also

12 References

13 Further reading

14 External links

Beginnings

The term Construction Art was first used as a derisive term by Kazimir Malevich to describe the work of Alexander Rodchenko in 1917.[citation needed] Constructivism first appears as a positive term in Naum Gabo's Realistic Manifesto of 1920. Aleksei Gan used the word as the title of his book Constructivism, printed in 1922.[1] Constructivism was a post-World War I development of Russian Futurism, and particularly of the 'counter reliefs' of Vladimir Tatlin, which had been exhibited in 1915. The term itself would be invented by the sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo, who developed an industrial, angular style of work, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich.

Constructivism as theory and practice was derived largely from a series of debates at the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK) in Moscow, from 1920 to 1922. After deposing its first chairman, Wassily Kandinsky, for his 'mysticism', The First Working Group of Constructivists (including Liubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin, Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and the theorists Aleksei Gan, Boris Arvatov and Osip Brik) would develop a definition of Constructivism as the combination of faktura: the particular material properties of an object, and tektonika, its spatial presence. Initially the Constructivists worked on three-dimensional constructions as a means of participating in industry: the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) exhibition showed these three dimensional compositions, by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Karl Ioganson and the Stenberg brothers. Later the definition would be extended to designs for two-dimensional works such as books or posters, with montage and factography becoming important concepts.

Art in the service of the Revolution

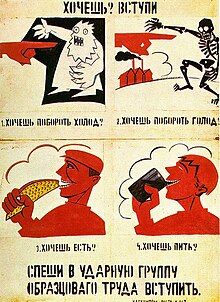

Agitprop poster by Mayakovsky

As much as involving itself in designs for industry, the Constructivists worked on public festivals and street designs for the post-October revolution Bolshevik government. Perhaps the most famous of these was in Vitebsk, where Malevich's UNOVIS Group painted propaganda plaques and buildings (the best known being El Lissitzky's poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919)). Inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky's declaration 'the streets our brushes, the squares our palettes', artists and designers participated in public life during the Civil War. A striking instance was the proposed festival for the Comintern congress in 1921 by Alexander Vesnin and Liubov Popova, which resembled the constructions of the OBMOKhU exhibition as well as their work for the theatre. There was a great deal of overlap during this period between Constructivism and Proletkult, the ideas of which concerning the need to create an entirely new culture struck a chord with the Constructivists. In addition some Constructivists were heavily involved in the 'ROSTA Windows', a Bolshevik public information campaign of around 1920. Some of the most famous of these were by the poet-painter Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vladimir Lebedev.

The constructivists tried to create works that would make the viewer an active viewer of the artwork. In this it had similarities with the Russian Formalists' theory of 'making strange', and accordingly their main theorist Viktor Shklovsky worked closely with the Constructivists, as did other formalists like the Arch Bishop. These theories were tested in theatre, particularly with the work of Vsevolod Meyerhold, who had established what he called 'October in the theatre'. Meyerhold developed a 'biomechanical' acting style, which was influenced both by the circus and by the 'scientific management' theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor. Meanwhile, the stage sets by the likes of Vesnin, Popova and Stepanova tested Constructivist spatial ideas in a public form. A more populist version of this was developed by Alexander Tairov, with stage sets by Aleksandra Ekster and the Stenberg brothers. These ideas would influence German directors like Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator, as well as the early Soviet cinema.

Tatlin, 'Construction Art' and Productivism

The key work of Constructivism was Vladimir Tatlin's proposal for the Monument to the Third International (Tatlin's Tower) (1919–20)[2] which combined a machine aesthetic with dynamic components celebrating technology such as searchlights and projection screens. Gabo publicly criticized Tatlin's design saying, "Either create functional houses and bridges or create pure art, not both." This had already caused a major controversy in the Moscow group in 1920 when Gabo and Pevsner's Realistic Manifesto asserted a spiritual core for the movement. This was opposed to the utilitarian and adaptable version of Constructivism held by Tatlin and Rodchenko. Tatlin's work was immediately hailed by artists in Germany as a revolution in art: a 1920 photograph shows George Grosz and John Heartfield holding a placard saying 'Art is Dead – Long Live Tatlin's Machine Art', while the designs for the tower were published in Bruno Taut's magazine Fruhlicht. The tower was never built, however, due to a lack of money following the revolution.[3]

Tatlin's tower started a period of exchange of ideas between Moscow and Berlin, something reinforced by El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehrenburg's Soviet-German magazine Veshch-Gegenstand-Objet which spread the idea of 'Construction art', as did the Constructivist exhibits at the 1922 Russische Ausstellung in Berlin, organised by Lissitzky. A Constructivist International was formed, which met with Dadaists and De Stijl artists in Germany in 1922. Participants in this short-lived international included Lissitzky, Hans Richter, and László Moholy-Nagy. However the idea of 'art' was becoming anathema to the Russian Constructivists: the INKhUK debates of 1920–22 had culminated in the theory of Productivism propounded by Osip Brik and others, which demanded direct participation in industry and the end of easel painting. Tatlin was one of the first to attempt to transfer his talents to industrial production, with his designs for an economical stove, for workers' overalls and for furniture. The Utopian element in Constructivism was maintained by his 'letatlin', a flying machine which he worked on until the 1930s.

Constructivism and consumerism

In 1921, the New Economic Policy was established in the Soviet Union, which opened up more market opportunities in the Soviet economy. Rodchenko, Stepanova, and others made advertising for the co-operatives that were now in competition with other commercial businesses. The poet-artist Vladimir Mayakovsky and Rodchenko worked together and called themselves "advertising constructors". Together they designed eye-catching images featuring bright colours, geometric shapes, and bold lettering. The lettering of most of these designs was intended to create a reaction, and function emotionally – most were designed for the state-owned department store Mosselprom in Moscow, for pacifiers, cooking oil, beer and other quotidian products, with Mayakovsky claiming that his 'nowhere else but Mosselprom' verse was one of the best he ever wrote.

Additionally, several artists tried to work with clothes design with varying success: Varvara Stepanova designed dresses with bright, geometric patterns that were mass-produced, although workers' overalls by Tatlin and Rodchenko never achieved this and remained prototypes. The painter and designer Lyubov Popova designed a kind of Constructivist flapper dress before her early death in 1924, the plans for which were published in the journal LEF. In these works, Constructivists showed a willingness to involve themselves in fashion and the mass market, which they tried to balance with their Communist beliefs.

LEF and Constructivist cinema

Constructivist Martian set in Aelita (1924)

The Soviet Constructivists organised themselves in the 1920s into the 'Left Front of the Arts', who produced the influential journal LEF, (which had two series, from 1923–5 and from 1927–9 as New LEF). LEF was dedicated to maintaining the avant-garde against the critiques of the incipient Socialist Realism, and the possibility of a capitalist restoration, with the journal being particularly scathing about the 'NEPmen', the capitalists of the period. For LEF the new medium of cinema was more important than the easel painting and traditional narratives that elements of the Communist Party were trying to revive then. Important Constructivists were very involved with cinema, with Mayakovsky acting in the film The Young Lady and the Hooligan (1919), Rodchenko's designs for the intertitles and animated sequences of Dziga Vertov's Kino Eye (1924), and Aleksandra Ekster designs for the sets and costumes of the science fiction film Aelita (1924).

The Productivist theorists Osip Brik and Sergei Tretyakov also wrote screenplays and intertitles, for films such as Vsevolod Pudovkin's Storm over Asia (1928) or Victor Turin's Turksib (1929). The filmmakers and LEF contributors Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein as well as the documentarist Esfir Shub also regarded their fast-cut, montage style of filmmaking as Constructivist. The early Eccentrist movies of Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg (The New Babylon, Alone) had similarly avant-garde intentions, as well as a fixation on jazz-age America which was characteristic of the philosophy, with its praise of slapstick-comedy actors like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, as well as of Fordist mass production. Like the photomontages and designs of Constructivism, early Soviet cinema concentrated on creating an agitational effect by montage and 'making strange'.

Photography and photomontage

The Constructivists were early developers of the techniques of photomontage. Gustav Klutsis' 'Dynamic City' and 'Lenin and Electrification' (1919–20) are the first examples of this method of montage, which had in common with Dadaism the collaging together of news photographs and painted sections. However Constructivist montages would be less 'destructive' than those of Dadaism. Perhaps the most famous of these montages was Rodchenko's illustrations of the Mayakovsky poem About This.

LEF also helped popularise a distinctive style of photography, involving jagged angles and contrasts and an abstract use of light, which paralleled the work of László Moholy-Nagy in Germany: the major practitioners of this included, along with Rodchenko, Boris Ignatovich and Max Penson, among others. This also shared many characteristics with the early documentary movement.

Constructivist graphic design

'Proun Vrashchenia' by El Lissitzky, 1919

The book designs of Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and others such as Solomon Telingater and Anton Lavinsky were a major inspiration for the work of radical designers in the West, particularly Jan Tschichold. Many Constructivists worked on the design of posters for everything from cinema to political propaganda: the former represented best by the brightly coloured, geometric posters of the Stenberg brothers (Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg), and the latter by the agitational photomontage work of Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina.

In Cologne in the late 1920s Figurative Constructivism emerged from the Cologne Progressives, a group which had links with Russian Constructivists, particularly Lissitzky, since the early twenties. Through their collaboration with Otto Neurath and the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum such artists as Gerd Antz, Augustin Tschinkel and Peter Alma they affected the development of the Vienna Method. This link was most clearly shown in A bis Z a journal published by Franz Seiwert the principal theorist of the group.[4] They were active in Russia working with IZOSTAT and Tschinkel worked with Ladislav Sutnar before he emigrated to the US.

The Constructivists' main early political patron was Leon Trotsky, and it began to be regarded with suspicion after the expulsion of Trotsky and the Left Opposition in 1927-8. The Communist Party would gradually favour realist art during the course of the 1920s (as early as 1918 Pravda had complained that government funds were being used to buy works by untried artists). However it was not until about 1934 that the counter-doctrine of Socialist Realism was instituted in Constructivism's place. Many Constructivists continued to produce avantgarde work in the service of the state, such as Lissitzky, Rodchenko and Stepanova's designs for the magazine USSR In Construction.

Constructivist architecture

Constructivist architecture emerged from the wider constructivist art movement. After the Russian Revolution of 1917 it turned its attentions to the new social demands and industrial tasks required of the new regime. Two distinct threads emerged, the first was encapsulated in Antoine Pevsner's and Naum Gabo's Realist manifesto which was concerned with space and rhythm, the second represented a struggle within the Commissariat for Enlightenment between those who argued for pure art and the Productivists such as Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and Vladimir Tatlin, a more socially oriented group who wanted this art to be absorbed in industrial production.[5]

A split occurred in 1922 when Pevsner and Gabo emigrated. The movement then developed along socially utilitarian lines. The productivist majority gained the support of the Proletkult and the magazine LEF, and later became the dominant influence of the architectural group O.S.A., directed by Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg.

Legacy

A number of Constructivists would teach or lecture at the Bauhaus schools in Germany, and some of the VKhUTEMAS teaching methods were adopted and developed there. Gabo established a version of Constructivism in England during the 1930s and 1940s that was adopted by architects, designers and artists after World War I (see Victor Pasmore), and John McHale. Joaquín Torres García and Manuel Rendón were instrumental in spreading Constructivism throughout Europe and Latin America. Constructivism had an effect on the modern masters of Latin America such as: Carlos Mérida, Enrique Tábara, Aníbal Villacís, Theo Constanté, Oswaldo Viteri, Estuardo Maldonado, Luis Molinari, Carlos Catasse, João Batista Vilanova Artigas and Oscar Niemeyer, to name just a few. There have also been disciples in Australia, the painter George Johnson being the best known.

In the 1980s graphic designer Neville Brody used styles based on Constructivist posters that initiated a revival of popular interest. Also during the 1980s designer Ian Anderson founded The Designers Republic, a successful and influential design company which used constructivist principles.

So-called Deconstructivist architecture was developed by architects Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas and others during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Zaha Hadid by her sketches and drawings of abstract triangles and rectangles evokes the aesthetic of constructivism. Though similar formally, the socialist political connotations of Russian constructivism are deemphasized by Hadid's deconstructivism. Rem Koolhaas' projects revive another aspect of constructivism. The scaffold and crane-like structures represented by many constructivist architects are used for the finished forms of his designs and buildings.

Artists closely associated with Constructivism

Ella Bergmann-Michel – (1896–1971)

Norman Carlberg, sculptor (1928–)

Avgust Černigoj – (1898–1985)

John Ernest – (1922–1994)

Naum Gabo – (1890–1977)

Moisei Ginzburg, architect (1892–1946)

Hermann Glöckner, painter and sculptor (1889–1987)

Erwin Hauer – (1926–)

Hildegard Joos, painter (1909-2005)

Gustav Klutsis – (1895–1938)

Katarzyna Kobro - (1898-1951)

Srečko Kosovel - (1904-1926)

Jan Kubíček - (1927-2013)

El Lissitzky – (1890–1941)

Ivan Leonidov – architect (1902–1959)

Richard Paul Lohse – painter and designer (1902–1988)

Peter Lowe – (1938–)

Louis Lozowick – (1892–1973)

Berthold Lubetkin – architect (1901–1990)

Thilo Maatsch – (1900–1983)

Estuardo Maldonado – (1930–)

Kenneth Martin – (1905–1984)

Mary Martin – (1907–1969)

Konstantin Medunetsky – (1899–1935)

Konstantin Melnikov – architect (1890–1974)

Vadim Meller – (1884–1962)

László Moholy-Nagy – (1895–1946)

Victor Pasmore – (1908–1998)

Laszlo Peri - artist and architect (1899-1967)

Antoine Pevsner – (1886–1962)

Lyubov Popova – (1889–1924)

Alexander Rodchenko – (1891–1956)

Kurt Schwitters – (1887–1948)

Manuel Rendón Seminario – (1894–1982)

Vladimir Shukhov – architect (1853–1939)

Anton Stankowski – painter and designer (1906–1998)

Jeffrey Steele – (1931–)

Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg – poster designers and sculptors (1900–1933, 1899–1982)

Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958)

Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953)

Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949)

Vasiliy Yermilov (1894–1967)

Alexander Vesnin – architect, painter and designer (1883–1957)

See also

- Suprematism

- Anti-art

- Cubist sculpture

References

^ Catherine Cooke, Russian Avant-Garde: Theories of Art, Architecture and the City, Academy Editions, 1995, page 106.

^ Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 819. .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 9781856695848

^ Janson, H.W. (1995) History of Art. 5th edn. Revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 820.

ISBN 0500237018

^ Benus B. (2013) 'Figurative Constructivism and sociological graphics' in Isotype: Design and Contexts 1925-71 London: Hyphen Press, pp.216-248

^ Oliver Stallybrass, and Alan Bullock (et al.) (1988). The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (Paperback). Fontana press. p. 918 pages. ISBN 0-00-686129-6.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Russian Constructivist Posters, edited by Elena Barkhatova.

ISBN 2-08-013527-9.- Baum, Stephen. The Documents of 20th-Century Art: The Tradition of Constructivism. The Viking Press. 1974. SBN 670-72301-0

- Heller, Steven, and Seymour Chwast. Graphic Style from Victorian to Digital. New ed. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001. 53–57.

- Lodder, Christina. Russian Constructivism. Yale University Press; Reprint edition. 1985.

ISBN 0-300-03406-7 - Rickey, George. Constructivism: Origins and Evolution. George Braziller; Revised edition. 1995.

ISBN 0-8076-1381-9 - Alan Fowler. Constructivist Art in Britain 1913–2005. University of Southampton. 2006. PhD Thesis.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constructivism. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Constructivism (art) |

- Resource on constructivism, focusing primarily on the movement in Russia and east-central Europe

- Documentary on Constructivist architecture

- Constructivist Book Covers

- Russian Constructivism. MoMA.org

- International Constructivism. MoMA.org

The Influence of Interpersonal Relationships on the Functioning of the Constructivist Network - an article by Michał Wenderski