Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793

| The Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolution | |||||

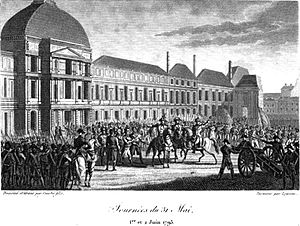

Hanriot confronts deputies of the Convention Pierre-Gabriel Berthault en 1804 | |||||

| |||||

The insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793 (French: journées), during the French Revolution, resulted in the fall of the Girondin party under pressure of the Parisian sans-culottes, Jacobins of the clubs, and Montagnards in the National Convention. By its impact and importance, this insurrection stands as one of the three great popular insurrections of the French Revolution, following those of 14 July 1789 and 10 August 1792.[1]

Contents

1 Background

2 Toward the crisis

3 Friday, 31 May

4 End of the Gironde

5 Aftermath

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Sources

Background

During the government of the Legislative Assembly (October 1791-September 1792), Girondins had dominated French politics.[2]

After the start of the newly elected National Convention in September 1792, the Girondin faction (c. 150) was larger than the montagnards (c. 120); most ministries were in the hands of friends or allies of the Girondins,[3] also the state bureaucracy and the provinces remained under their control.

France was expecting the Convention to deliver its Constitution; instead, by the spring of 1793 it had civil war, invasion, difficulties and dangers.[4][note 1]

The economic situation was deteriorating rapidly. By the end of the winter, grain circulation had stopped completely and grain prices doubled. Against Saint-Just's advice, vast quantities of assignats were still being put in circulation. In February 1793, they had fallen to 50 per cent of their face value. The depreciation provoked inflation and speculation.[6]

Military setbacks against the First Coalition, Dumouriez's treason and the War in the Vendée which had begun in March 1793 drove many republicans towards the montagnards. The Girondins were forced to accept the creation of the Committee of Public Safety and Revolutionary Tribunal.[7]

While the inability of the Gironde to fend off all those dangers became evident, the montagnards, in their determination to "save the Revolution", were gradually adopting the political program proposed by the popular militants.[8]

Authority was passing into hands of the 150 montagnards delegated to the départements and armed forces. The Gironde saw its influence decline in the interior and the number of anti-Brissot petitions increased by late March 1793.[9]

Toward the crisis

Le triomphe de Marat, Louis-Léopold Boilly, 1794

On 5 April the Jacobins, presided by Marat, sent a circular letter to popular societies in the provinces inviting them to ask for the recall and dismissal of those appelants, who had voted for the decision to execute the King to be referred back to the people. On 13 April Guadet proposed that Marat be charged for having, as president of the club, signed that circular, and this proposal was passed by the Convention by 226 votes to 93, with 47 abstentions, following an angry debate. Marat's case was passed to the Revolutionary Tribunal, where Marat offered himself as "the apostle and martyr of liberty", and he was triumphantly acquitted on 24 April. Already on the 15th, thirty-five of the forty-eight Paris sections had presented a petition to the Convention couched in the most threatening terms against the twenty-two most prominent Girondins.[clarification needed][10]

The Gironde turned its attack on the very citadel of Montagnard power, the Paris Commune. In his reply to Camille Desmoulins's Histoire des Brissotins, which was read at Jacobins on 17 May, the next day Guadet denounced the Paris authorities in the Convention, describing them as "authorities devoted to anarchy, and greedy for both money and political domination": his proposal was that they be immediately quashed.[clarification needed] A commission of inquiry of twelve members was at once set up, on which only Girondins sat. This Commission of Twelve ordered the arrest of Hébert on 24 May for the anti-girondin article in number 239 of the Pere Duchesne. Other popular militants were arrested, including Varlet and Dobsen, the president of the Cite section. These measures brought on the final crisis.[11]

On 25 May the Commune demanded that arrested patriots be released. In reply, Isnard, who was presiding over the Convention, launched into a bitter diatribe against Paris which was infuriatingly reminiscent of the Brunswick Manifesto: "If any attack made on the persons of the representatives of the nation, then I declare to you in the name of the whole country that Paris would be destroyed; soon people would be searching along the banks of the Seine to find out whether Paris had ever existed".

On the next day, at the Jacobin Club, Robespierre called on the people to revolt. The Jacobins declared themselves in a state of insurrection.

On 28 May the Cite section called the other sections to a meeting the following day at the Évêché (the Bishop's Palace) in order to organize the insurrection. Varlet and Dobsen had been freed from prison the previous day on the orders of the Convention and were present at the meeting, which was attended only by the Montagne and by the members of the Plain. On the 29th the delegates representing thirty-three of the sections formed an insurrectionary committee of nine.[11]

Most of its members were comparatively young men and little known. Varlet had, indeed, made his name as an agitator; Hassenfratz held an important post in the War Office; Dobsen had been foremen of the jury in the Revolutionary Tribunal; Rousselin edited the Feuille du salut public. But who had ever heard of the printer Marquet, who presided over the Central Committee, or of its secretary Tombe? Who had ever heard of the painter Simon of the Halle-au-Blé section, of the toy-maker Bonhommet, of Auvray, an usher from Montmartre, of Crepin the decorator, of Caillieaux the ribbon-maker, or of the declasse aristocrat Duroure? Yet these unknown men purported to be the voice of the people. They were all Frenchmen and they were all Parisians and not novices in revolution.[12]

On 30 May the department gave its support to the movement.

Friday, 31 May

The insurrection started on 31 May and directed by the committee at the Évêché (the Bishop's Palace Committee), developed according to the methods already tested on 10 August. At six o'clock in the morning the delegates of the 33 sections, led by Dobsen, presented themselves at Hôtel de Ville, showed the full powers with which the members had invested them, and suppressed the Commune, whose members had retired to the adjourning room. Next the revolutionary delegates provisionally reinstated the Commune in its functions.

The insurgent committee, which was now sitting at the Hôtel de Ville, dictated to the Commune, now reinstated by the people, what measures it was to take. It secured the nomination of François Hanriot, commandant of the battalion of the Jardin des Plantes, as sole commander-in-chief of the National Guard of Paris. It was decided that the poorer National Guards who were under arms should receive pay at the rate of 40 sous a day. The alarm-gun was fired towards noon. The assembly of the Parisian authorities, summoned by the departmental assembly, resolved to cooperate with the Commune and the insurrectionary committee, whose numbers were raised to 21 by the addition of delegates from the meeting at the Jacobins.[13] Hanriot's first care was to seize the key positions—the Arsenal, the Place Royale, and the Pont Neuf. Next the barriers were closed and prominent suspects arrested.[14]

The sections were very slow in getting under way. 31 May was a Friday, so the workers were at their jobs. The demonstration took shape only in the afternoon. The Convention assembled at the sound of the tocsin and of the drum beating to arms. Girondins protested against the closing of the city gates and against the tocsin and alarm-gun. Petitioners from the sections and the Commune appeared at the bar of the Convention at about five o'clock in the afternoon. They demanded that 22 Girondin deputée and members of the Commission of Twelve should be broight before the Revolutionary Tribunal, that a central revolutionary army should be raised, that the price of bread should be fixed at three sous a pound, that nobles holding senior rank in the army should be dismissed, that armories should be created for arming the sans-culottes, the departments of State purged, suspects arrested, the right to vote provisionally reserved to sans-culottes only, and a fund set apart for the relatives of those defending their country and for the relief of aged and infirm.

The petitioners made their way into the hall and sat down besides the Montagnards. Robespierre ascended the tribune and supported the suppression of the commissions. When Vergniaud called upon him to conclude, Robespierre turned towards him and said: "Yes, I will conclude, but it will be against you! Against you, who, after the revolution 10 August, wanted to send those responsible for it to the scaffold; against you, who have never ceased to incite to the destruction of Paris; against you, who wanted to save the tyrant; against you, who conspired with Dumouriez... Well my conclusion is: the prosecution of all Dumouriez's accomplices and all those whose names have been mentioned by the petitioners..." To this Vergniaud did not reply. The Convention suppressed the Commission of Twelve and approved the ordinance of the Commune granting two livres a day to workmen under arms.[15]

Yet the rising of 31 May ended unsatisfactorily. That evening at the Commune, Chaumette and Dobsen were accused by Varlet of weakness. Robespierre had declared from the tribune that the journee of 31 May was not enough. At the Jacobins Billaud-Varenne echoed: "Our country is not saved; there were important measures of public safety that had to be taken; it was today that we had to strike the final blows against factionalism". The Commune declaring itself duped, demanded and prepared a "supplement" to the revolution.[16]

End of the Gironde

Arrest of the Girondins at the National Convention on 2 June 1793

On 1 June the National Guard remained under arms. Marat himself repaired to the Hôtel de Ville, and gave, with emphatic solemnity, a "counsel" to the people; namely, to remain at the ready and not to quit until victory was theirs. He himself climbed to the belfry of the Hôtel de Ville and rang the tocsin. The Convention broke the session at six o'clock, at the time when the Commune was to present a new petition against the twenty-two. At the tocsin sound it assembled again and the petition demanding the arrest of the Girondins was referred to the Committee of Public Safety for examination and report within three days.[16]

During the night 1–2 June insurrectionary committee, by agreement with the Commune, ordered Hanriot to "surround the Convention with an armed force sufficient to command respect, in order that the chiefs of the faction may be arrested during the day, in case the Convention refused to accede to the request of the citizens of Paris". Orders were given to suppress the Girondin newspapers and arrest their editors.[17]

2 June was a Sunday. Workmen thronged to obey Hanriot's orders, and soon eighty thousand men, armed with cannons, surrounded the Tuileries. The session of the Convention opened with bad news: the chief town of the Vendee, had just fallen into hands of rebels. At Lyons royalist and Girondin sections had gained control of the Hotel de Ville after a fierce struggle, in which it was said that eight hundred republicans had perished.

In the Convention, Lanjuinais denounced the revolt of the Paris Commune and asked for its suppression. "I demand," said he, "to speak respecting the general call to arms now beating throughout Paris." He was immediately interrupted by cries of "Down! down! He wants civil war! He wants a counter-revolution! He defames Paris! He insults the people." Despite the threats, the insults, the clamours of the Mountain and the galleries, Lanjuinais denounced the projects of the commune and of the malcontents; his courage rose with the danger. "You accuse us," he said, "of defaming Paris! Paris is pure; Paris is good; Paris is oppressed by tyrants who thirst for blood and dominion." These words were the signal for the most violent tumult; several Mountain deputies rushed to the tribune to tear Lanjuinais from it; but he, clinging firmly to it, exclaimed, in accents of the most lofty courage, "I demand the dissolution of all the revolutionist authorities in Paris. I demand that all they have done during the last three days may be declared null. I demand that all who would arrogate to themselves a new authority contrary to law, be placed outside the law, and that every citizen be at liberty to punish them." He had scarcely concluded, when the insurgent petitioners came to demand his arrest, and that of his colleagues. "Citizens," said they, "the people are weary of seeing their happiness still postponed; they leave it once more in your hands; save them, or we declare that they will save themselves." The demand again was referred to the Committee of Public Safety.[18]

The petitioners went out shaking their fists at the Assembly and shouting: "To arms!". Strict orders were given by Hanriot forbidding the National Guard to let any deputy go in or out. In the name of the Committee of Public Safety, Barrère proposed a compromise. The twenty-two and the twelve were not to be arrested, but were called upon to voluntarily to suspend the exercise of their functions. Isnard and Fauchet obeyed on the spot. Others refused. While this was going on, Lacroix, a deputy of the Mountain, rushed into the Convention, hurried to the tribune, and declared that he had been insulted at the door, that he had been refused egress, and that the convention was no longer free. Many of the Mountain expressed their indignation at Hanriot and his troops. Danton said it was necessary to vigorously avenge this insult to the national honour. Barrère proposed that the members of the Convention present themselves to the people. "Representatives," said he, "vindicate your liberty; suspend your sitting; cause the bayonets that surround you to be lowered." [19]

At the prompting of Barrère, the whole Convention, except the left of the Montagne, started out, led by the president, Hérault de Séchelles, and attempted to exit their way through the wall of steel with which they were surrounded. On arriving at a door on the Place du Carrousel, they found there Hanriot on horseback, sabre in hand. "What do the people require?" said the president, Hérault de Séchelles; "the convention is wholly engaged in promoting their happiness." "Hérault," replied Hanriot, "the people have not risen to hear phrases; they require twenty-four traitors to be given up to them."[note 2] "Give us all up!" cried those who surrounded the president. Hanriot then turned to his people, and gave the order: "Canonniers, a vos pieces!" ("Cannoneers, to your guns!"). [19]

The Assembly walked round the palace, repulsed by bayonets on all sides, only to return and submit.[21] On the motion of Couthon the Convention voted for the suspension and house arrest (arrestation chex eux) under the guard of a gendarme of twenty-nine Girondin members together with ministers Claviere and Lebrun.[14][note 3]

Aftermath

Thus the struggle which had begun in the Legislative Assembly ended in the triumph of the Montagnards. The Gironde ceased to be a political force. It had declared war without knowing how to conduct it; it had denounced the King but had shrunk from condemning him; it had contributed to the worsening of the economic crisis but had swept aside all the claims made by the popular movement.[22]

The 31 May soon came to be regarded as one of the great journees of the Revolution. It shared with 14 July 1789 and 10 August 1792 the honor of having a ship of the line named after it. But the results of the crisis left all the participants dissatisfied. Danton's hopes of last-minute compromise had been shattered. Although the Montagnards had succeeded in averting bloodshed the outrage to the Assembly might well set the provinces on fire. But the Montagnards now had a chance to govern the country and to infuse new energy into national defense.[23]

Though for the popular movement most of the demands presented to the Convention were not achieved, the insurrection 31 May – 2 June 1793 inaugurated new phase in the Revolution. In the course of summer 1793 Revolutionary government was created, maximum and price controls were introduced and Jacobin republic began its offensive against the enemies of the Revolution.

See also

- National Convention

- Girondins

- Montagnards

- Enragés

- Sans-culottes

- Georges Danton

- Maximilien Robespierre

- Jean-Paul Marat

- Federalist revolts

Notes

^ In an interesting letter to Danton, dated 6 May, Tom Paine analysed the position as he saw it. He has stayed in France, he says, instead of returning to America, in the hope of seeing the principles of the revolution spread throughout Europe. Now he despairs of this event. The internal state of France is such that the revolution itself is in danger. The way in which the provincial deputies are insulted by the Parisians will lead to a rupture between the capital and departments, unless the Convention is moved elsewhere. France should profit by American experience in this matter, and hold its Congress outside the limits of any municipality. American experience shows (he thinks) that the maximum (price control) cannot be worked on a national, but only on municipal basis. Paine also insists on the need of staying the inflation of paper currency. But the greatest danger he signalizes is "the spirit of denunciation that now prevails". [5]

^ Mignet quote is a mild version of the Hanriot's reply. Historian David Bell in his review «When Terror Was Young» of David Andress' book «The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France» gives harsher version of the same reply: "Tell your fucking president that he and his Assembly are fucked, and that if within one hour he doesn’t deliver to me the Twenty-two I’m going to blast it to the ground". In his view (David Bell's) "such were the words, uttered by the sans-culotte commander Hanriot, cannon literally in hand, by which France’s fledgling democracy died" and even the very language underlines it. For François Furet it was "the confrontation between national representation and direct democracy personified in brute force of the poorer classes and their guns". [20]

^ Arrested Girondins:

Barbaroux, Chambon, Brissot, Buzot, Birotteau, Gensonné, Gorsas, Grangeneuve, Guadet, Lanjuinais, Lasource, Lehardy, Lesage, Lidon, Louvet, Pétion, Salle, Valazé, Vergniaud, Bergoeing, Boilleau, Gardien, Gomaire, Kervélégan, La Hosdinière, Henry-Larivière, Mollevaut, Rabaut, Viger

References

^ Hampson 1988, p. 178.

^ (in Dutch) Noah Shusterman – De Franse Revolutie (The French Revolution). Veen Media, Amsterdam, 2015. (Translation of: The French Revolution. Faith, Desire, and Politics. Routledge, London/New York, 2014.) Chapter 5 (p. 187–221) : The end of the monarchy and the September Murders (summer–fall 1792).

^ (in Dutch) Noah Shusterman – De Franse Revolutie (The French Revolution). Veen Media, Amsterdam, 2015. (Translation of: The French Revolution. Faith, Desire, and Politics. Routledge, London/New York, 2014.) Chapter 6 (p. 223–269) : The new French republic and its enemies (fall 1792–summer 1793).

^ Bouloiseau 1983, p. 64.

^ Thompson 1959, p. 350.

^ Bouloiseau 1983, p. 61.

^ Soboul 1974, p. 302.

^ Soboul 1974, p. 303.

^ Bouloiseau 1983, p. 65.

^ Soboul 1974, p. 307.

^ ab Soboul 1974, p. 309.

^ Thompson 1959, p. 353.

^ Mathiez 1929, p. 323.

^ ab Thompson 1959, p. 354.

^ Mathiez 1929, p. 324.

^ ab Aulard 1910, p. 110.

^ Mathiez 1929, p. 325.

^ Mignet 1824, p. 297.

^ ab Mignet 1824, p. 298.

^ Furet 1996, p. 127.

^ Mathiez 1929, p. 326.

^ Soboul 1974, p. 311.

^ Hampson 1988, p. 180.

Sources

Aulard, François-Alphonse (1910). The French Revolution, a Political History, 1789-1804, in 4 vols. Vol. III. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Bouloiseau, Marc (1983). The Jacobin Republic: 1792-1794. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28918-1.

Furet, François (1996). The French Revolution: 1770–1814. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-631-20299-4.

Hampson, Norman (1988). A Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-710-06525-6.

Mathiez, Albert (1929). The French Revolution. New York: Alfred a Knopf.

Mignet, François (1824). History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814. Project Gutenberg EBook.

Slavin, Morris (1999). "Robespierre and the Insurrection of 31 May–2 June 1793". In Colin Haydon; William Doyle. Robespierre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Soboul, Albert (1974). The French Revolution:: 1787-1799. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-47392-2.

Thompson, J. M. (1959). The French Revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.