Nunavut

Nunavut .mw-parser-output .noboldfont-weight:normal ᓄᓇᕗᑦ (Inuktitut) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Motto(s): ᓄᓇᕗᑦ ᓴᙱᓂᕗᑦ (Inuktitut) "Nunavut Sannginivut" "Our land, our strength" "Notre terre, notre force" | |||

BC AB SK MB ON QC NB PE NS NL YT NT NU  | |||

| Confederation | April 1, 1999 (19 years ago) (13th) | ||

| Capital | Iqaluit | ||

| Largest city | Iqaluit | ||

| Government | |||

| • Commissioner | Nellie Kusugak | ||

| • Premier | Joe Savikataaq (consensus government) | ||

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly of Nunavut | ||

| Federal representation | (in Canadian Parliament) | ||

| House seats | 1 of 338 (0.3%) | ||

| Senate seats | 1 of 105 (1%) | ||

| Area[1] | |||

| • Total | 2,038,722 km2 (787,155 sq mi) | ||

| • Land | 1,877,787 km2 (725,018 sq mi) | ||

| • Water | 160,935 km2 (62,137 sq mi) 7.9% | ||

| Area rank | Ranked 1st | ||

| 20.4% of Canada | |||

| Population (2016) | |||

| • Total | 35,944 [1] | ||

| • Estimate (2018 Q3) | 38,396 [2] | ||

| • Rank | Ranked 12th | ||

| • Density | 0.02/km2 (0.05/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Nunavummiut Nunavummiuq (sing.)[3] | ||

| Official languages | English French Inuit languages (Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun)[4] | ||

GDP | |||

| • Rank | 13th | ||

| • Total (2011) | C$1.964 billion[5] | ||

| • Per capita | C$58,452 (6th) | ||

| Time zone | UTC-5, UTC-6, UTC-7 | ||

| Postal abbr. | NU | ||

| Postal code prefix | X | ||

| ISO 3166 code | CA-NU | ||

| Flower | Purple Saxifrage[6] | ||

| Tree | n/a | ||

| Bird | Rock Ptarmigan[7] | ||

| Website | www.gov.nu.ca | ||

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |||

Nunavut (/nuːnəˌvuːt/ (![]() listen);[8]French: [nynavy(t)]; Inuktitut syllabics ᓄᓇᕗᑦ [ˈnunavut]) is the newest, largest, and northernmost territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the Nunavut Act[9] and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act,[10] though the boundaries had been contemplatively drawn in 1993. The creation of Nunavut resulted in the first major change to Canada's political map since the incorporation of the province of Newfoundland in 1949.

listen);[8]French: [nynavy(t)]; Inuktitut syllabics ᓄᓇᕗᑦ [ˈnunavut]) is the newest, largest, and northernmost territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the Nunavut Act[9] and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act,[10] though the boundaries had been contemplatively drawn in 1993. The creation of Nunavut resulted in the first major change to Canada's political map since the incorporation of the province of Newfoundland in 1949.

Nunavut comprises a major portion of Northern Canada, and most of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Its vast territory makes it the fifth-largest country subdivision in the world, as well as North America's second-largest (after Greenland). The capital Iqaluit (formerly "Frobisher Bay"), on Baffin Island in the east, was chosen by the 1995 capital plebiscite. Other major communities include the regional centres of Rankin Inlet and Cambridge Bay.

Nunavut also includes Ellesmere Island to the far north, as well as the eastern and southern portions of Victoria Island in the west and Akimiski Island in James Bay far to the southeast of the rest of the territory. It is Canada's only geo-political region that is not connected to the rest of North America by highway.[11]

Nunavut is the largest in area and the second-least populous of Canada's provinces and territories. One of the world's most remote, sparsely settled regions, it has a population of 35,944,[1] mostly Inuit, spread over an area of just over 1,750,000 km2 (680,000 sq mi), or slightly smaller than Mexico. Nunavut is also home to the world's northernmost permanently inhabited place, Alert.[12]Eureka, a weather station also on Ellesmere Island, has the lowest average annual temperature of any Canadian weather station.[13]

Niungvaliruluit ("pointer like a window") inuksuk, Foxe peninsula, Baffin Island

Contents

1 Etymology

2 Geography

2.1 Climate

3 History

3.1 Archaeological findings

3.2 First written historical accounts

3.3 Cold War

3.4 Recent history

4 Demography

4.1 Language

4.2 Religion

5 Economy

5.1 Mining and exploration

5.2 Advancing mining projects

5.3 Historic mines

5.4 Transportation

5.5 Renewable power

6 Government and politics

6.1 Licence plates

6.2 Flag and coat of arms

7 Culture

7.1 Music

7.2 Media

7.3 Film

7.4 Performing arts

7.5 Nunavummiut (notable people)

7.6 Alcohol

7.7 Sport

8 See also

9 Footnotes

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Etymology

Nunavut means "our land" in Inuktitut.[14]

Geography

Nunavut covers 1,877,787 km2 (725,018 sq mi)[1] of land and 160,935 km2 (62,137 sq mi)[15] of water in Northern Canada. The territory includes part of the mainland, most of the Arctic Archipelago, and all of the islands in Hudson Bay, James Bay, and Ungava Bay, including the Belcher Islands, all of which belonged to the Northwest Territories from which Nunavut was separated. This makes it the fifth-largest subnational entity (or administrative division) in the world. If Nunavut were a country, it would rank 15th in area.[16]

Nunavut has long land borders with the Northwest Territories on the mainland and a few Arctic islands, and with Manitoba to the south of the Nunavut mainland; it also meets Saskatchewan to the southwest at a quadripoint). Through its small satellite territories in the southeast, it has short land borders with Newfoundland and Labrador on Killiniq Island, with Ontario in two locations in James Bay – the larger located west of Akimiski Island, and the smaller around the Albany River near Fafard Island – and with Quebec in many locations, such as near Eastmain and near Inukjuak. It also shares maritime borders with Greenland and the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba.

Nunavut's highest point is Barbeau Peak (2,616 m (8,583 ft)) on Ellesmere Island. The population density is 0.019 persons/km2 (0.05 persons/sq mi), one of the lowest in the world. By comparison, Greenland has approximately the same area and nearly twice the population.[17]

Climate

Köppen climate types in Nunavut

Nunavut experiences a polar climate in most regions, owing to its high latitude and lower continental summertime influence than areas to the west. In more southerly continental areas very cold subarctic climates can be found, due to July being slightly milder than the required 10 °C (50 °F).

| City | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | |

| Alert | 6 | 1 | 43 | 33 | −29 | −36 | −20 | −33 |

| Baker Lake | 17 | 6 | 63 | 43 | −28 | −35 | −18 | −31 |

| Cambridge Bay | 13 | 5 | 55 | 41 | −29 | −35 | −19 | −32 |

| Eureka | 9 | 3 | 49 | 37 | −33 | −40 | −27 | −40 |

| Iqaluit | 12 | 4 | 54 | 39 | −23 | −31 | −9 | −24 |

| Kugluktuk | 16 | 6 | 60 | 43 | −23 | −31 | −10 | −25 |

| Rankin Inlet | 15 | 6 | 59 | 43 | −27 | −34 | −17 | −30 |

History

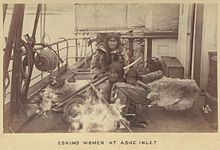

Inuit women at Ashe Inlet, 1884.

The region now known as Nunavut has supported a continuous indigenous population for approximately 4,000 years. Most historians identify the coast of Baffin Island with the Helluland described in Norse sagas, so it is possible that the inhabitants of the region had occasional contact with Norse sailors.

Archaeological findings

In September 2008, researchers reported on the evaluation of existing and newly excavated archaeological remains, including yarn spun from a hare, rats, tally sticks, a carved wooden face mask that depicts Caucasian features, and possible architectural material. The materials were collected in five seasons of excavation at Cape Tanfield. Scholars determined that these provide evidence of European traders and possibly settlers on Baffin Island, not later than 1000 CE (and thus older than or contemporaneous with L'Anse aux Meadows). They seem to indicate prolonged contact, possibly up to 1450. The origin of the Old World contact is unclear; the article states: "Dating of some yarn and other artifacts, presumed to be left by Vikings on Baffin Island, have produced an age that predates the Vikings by several hundred years. So […] you have to consider the possibility that as remote as it may seem, these finds may represent evidence of contact with Europeans prior to the Vikings' arrival in Greenland."[19]

Inuit village near Frobisher Bay, 1865

First written historical accounts

The written historical accounts of Nunavut begin in 1576, with an account by English explorer Martin Frobisher. While leading an expedition to find the Northwest Passage, Frobisher thought he had discovered gold ore around the body of water now known as Frobisher Bay on the coast of Baffin Island.[20] The ore turned out to be worthless, but Frobisher made the first recorded European contact with the Inuit. Other explorers in search of the elusive Northwest Passage followed in the 17th century, including Henry Hudson, William Baffin and Robert Bylot.

Cold War

Cornwallis and Ellesmere Islands featured in the history of the Cold War in the 1950s. Concerned about the area's strategic geopolitical position, the federal government relocated Inuit from Nunavik (northern Quebec) to Resolute and Grise Fiord. In the unfamiliar and hostile conditions, they faced starvation[21] but were forced to stay.[22] Forty years later, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report titled The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation.[23] The government paid compensation to those affected and their descendants and on August 18, 2010 in Inukjuak, Nunavik, the Honourable John Duncan, PC, MP, previous Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians apologized on behalf of the Government of Canada for the relocation of Inuit to the High Arctic.[24][25]

Glacially polished banded coloured marble on Baffin Island.

Recent history

Discussions on dividing the Northwest Territories along ethnic lines began in the 1950s, and legislation to do this was introduced in 1963. After its failure, a federal commission recommended against such a measure.[26]

In 1976, as part of the land claims negotiations between the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (then called the "Inuit Tapirisat of Canada") and the federal government, the parties discussed division of the Northwest Territories to provide a separate territory for the Inuit. On April 14, 1982, a plebiscite on division was held throughout the Northwest Territories. A majority of the residents voted in favour and the federal government gave a conditional agreement seven months later.[27]

The land claims agreement was completed in September 1992 and ratified by nearly 85% of the voters in Nunavut in a referendum. On July 9, 1993, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act[10] and the Nunavut Act[9] were passed by the Canadian Parliament. The transition to establish Nunavut Territory was completed on April 1, 1999.[28] The creation of Nunavut has been followed by growth in the capital, Iqaluit—a modest increase from 5,200 in 2001 to 6,600 in 2011.

Demography

As of the 2016 Canada Census, the population of Nunavut was 35,944, a 12.7% increase from 2011.[1] In 2006, 24,640 people identified themselves as Inuit (83.6% of the total population), 100 as First Nations (0.3%), 130 Métis (0.4%) and 4,410 as non-aboriginal (15.0%).[29]

| Municipality | 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | Growth 2011–16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Iqaluit | 7,082 | 6,699 | 6,184 | 10.3% |

Rankin Inlet | 2,441 | 1,905 | 1,528 | 28.1% |

Arviat | 2,318 | 2,060 | 12.5% | |

Baker Lake | 1,872 | 1,728 | 8.3% | |

Cambridge Bay | 1,619 | 1,452 | 1,377 | 11.5% |

Pond Inlet | 1,549 | 1,315 | 17.8% | |

Igloolik | 1,454 | 1,538 | −5.5% | |

Kugluktuk | 1,450 | 1,302 | 11.4% | |

Pangnirtung | 1,425 | 1,325 | 7.5% | |

Cape Dorset | 1,441 | 1,363 | 1,236 | 5.7% |

The population growth rate of Nunavut has been well above the Canadian average for several decades, mostly due to birth rates significantly higher than the Canadian average—a trend that continues. Between 2011 and 2016, Nunavut had the highest population growth rate of any Canadian province or territory, at a rate of 12.7%.[1] The second-highest was Alberta, with a growth rate of 11.6%.

Language

Along with the Inuit Language (Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun) sometimes called Inuktut,[30]English and French are also official languages.[4][31]

In his 2000 commissioned report (Aajiiqatigiingniq Language of Instruction Research Paper) to the Nunavut Department of Education, Ian Martin of York University stated a "long-term threat to Inuit languages from English is found everywhere, and current school language policies and practices on language are contributing to that threat" if Nunavut schools follow the Northwest Territories model. He provided a 20-year language plan to create a "fully functional bilingual society, in Inuktitut and English" by 2020. The plan provides different models, including:

- "Qulliq Model", for most Nunavut communities, with Inuktitut as the main language of instruction.

- "Inuinnaqtun Immersion Model", for language reclamation and immersion to revitalize Inuinnaqtun as a living language.

Kugluktuk

- "Mixed Population Model", mainly for Iqaluit (possibly for Rankin Inlet), as the 40% Qallunaat, or non-Inuit, population may have different requirements.[32]

Pangnirtung

Of the 34,960 responses to the census question concerning 'mother tongue' in the 2016 census, the most commonly reported languages were:

| Rank | Language | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inuktitut | 22,070 | 63.1% |

| 2 | English | 11,020 | 31.5% |

| 3 | French | 595 | 1.7% |

| 4 | Inuinnaqtun | 495 | 1.4% |

At the time of the census, only English and French were counted as official languages. Figures shown are for single-language responses and the percentage of total single-language responses.[33]

In the 2016 census it was reported that 2,045 people (5.8%) living in Nunavut had no knowledge of either official language of Canada (English or French).[34] The 2016 census also reported that of the 30,135 Inuit people in Nunavut, 90.7% could speak either Inuktitut or Inuinnaqtun.[citation needed]

Religion

The largest denominations by number of adherents according to the 2001 census were the Anglican Church of Canada with 15,440 (58%); the Roman Catholic Church (Roman Catholic Diocese of Churchill-Hudson Bay) with 6,205 (23%); and Pentecostal with 1,175 (4%).[35] In total, 93% of the population were Christian.

Economy

The economy of Nunavut is Inuit and Territorial Government, mining, oil gas mineral exploration, arts crafts, hunting, fishing, whaling, tourism, transportation, education - Nunavut Arctic College, housing, military and research – new Canadian High Arctic Research Station CHARS in planning for Cambridge Bay and high north Alert Bay Station.

Iqaluit hosts the annual Nunavut Mining Symposium every April[36], this is a tradeshow that showcases many economic activities on going in Nunavut.

Mining and exploration

There are currently three major mines in operation in Nunavut.

Agnico-Eagle Mines Ltd – Meadowbank Division. Meadowbank Gold Mine is an open pit gold mine with an estimated mine life 2010–2020 and employs 680 persons.

The second recently opened mine in production is the Mary River Iron Ore mine operated by Baffinland Iron Mines. It is located close to Pond Inlet on North Baffin Island. They produce a high grade direct ship iron ore.

The most recent mine to open is Doris North or the Hope Bay Mine operated near Hope Bay Aerodrome by TMAC Resource Ltd. This new high grade gold mine is the first in a series of potential mines in gold occurrences all along the Hope Bay greenstone belt.

Advancing mining projects

| Name | Company | In the region of | Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaruq and Meliadine Gold Projects | Agnico-Eagle | Rankin Inlet | Gold |

| Back River Project | Sabina Gold & Silver Corp. | Bathurst Inlet | Gold |

| Izok Corridor Project | MMG Resources Inc. | Kugluktuk | Gold, Copper, Silver, Zinc |

| Hackett River | Glencore | Kugluktuk | Copper, Lead, Silver, Zinc |

| Chidliak | Peregrine Diamonds Ltd. | Iqaluit / Pangnirtung | Diamonds |

| Committee Bay, Three Bluffs Gold Project | Auryn Resources Inc | Naujaat | Gold |

| Kiggavik | Areva Resources | Baker Lake | Uranium |

| Roche Bay | Advanced Exploration | Hall Beach | Iron Ore |

| Ulu and Lupin | Elgin Mining Ltd. | Contwoyto Lake - connected to Yellowknife with an ice road | Gold |

| Storm Copper Property | Aston Bay Holdings | Taloyoak | Copper |

Historic mines

Lupin Mine 1982–2005, gold, current owner Elgin Mining Ltd located near the Northwest Territories boundary near Contwoyto Lake)[37]

Polaris Mine 1982–2002, lead and zinc (located on Little Cornwallis Island, not far from Resolute)

Nanisivik Mine 1976–2002, lead and zinc, prior owner Breakwater Resources Ltd (near Arctic Bay) at Nanisivik

Rankin Nickel Mine 1957–1962, nickel, copper and platinum group metals

Jericho Diamond Mine 2006–2008, diamond (located 400 km, 250 mi, northeast of Yellowknife) 2012 produced diamonds from existing stockpile. No new mining; closed.- Doris North Gold Mine Newmont Mining approx 3 km (2 mi) underground drifting/mining, none milled or processed. Newmont closed the mine and sold it to TMAC Resources in 2013. TMAC has now reached commercial production in 2017.

Transportation

Northern Transportation Company Limited, owned by Norterra, a holding company that was, until April 1, 2014, jointly owned by the Inuvialuit of the Northwest Territories and the Inuit of Nunavut.[38][39][40][41]- There are no sidewalks in Nunavut.[42]

Renewable power

Open ocean absorbs more sunshine, while sea ice, shown here in Nunavut, reflects more, accelerating freezing.

Nunavut's people rely primarily on diesel fuel[43] to run generators and heat homes, with fossil fuel shipments from southern Canada by plane or boat because there are few to no roads or rail links to the region.[44] There is a government effort to use more renewable energy sources,[45] which is generally supported by the community.[46]

This support comes from Nunavut feeling the effects of global warming.[47][48] Former Nunavut Premier Eva Aariak said in 2011, "Climate change is very much upon us. It is affecting our hunters, the animals, the thinning of the ice is a big concern, as well as erosion from permafrost melting."[44] The region is warming about twice as fast as the global average, according to the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Government and politics

Legislative assembly building in Iqaluit

Nunavut has a Commissioner appointed by the federal Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs. As in the other territories, the commissioner's role is symbolic and is analogous to that of a Lieutenant-Governor.[49] While the Commissioner is not formally a representative of Canada's head of state, a role roughly analogous to representing The Crown has accrued to the position.

Nunavut elects a single member of the House of Commons of Canada. This makes Nunavut the largest electoral district in the world by area.

The members of the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Nunavut are elected individually; there are no parties and the legislature is consensus-based.[50] The head of government, the premier of Nunavut, is elected by, and from the members of the legislative assembly. On June 14, 2018, Joe Savikataaq was elected as the Premier of Nunavut, after his predecessor Paul Quassa lost a non-confidence motion.[51][52] Former Premier Paul Okalik set up an advisory council of eleven elders, whose function it is to help incorporate "Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit" (Inuit culture and traditional knowledge, often referred to in English as "IQ") into the territory's political and governmental decisions.[53]

Due to the territory's small population, and the fact that there are only a few hundred voters in each electoral district, the possibility of two election candidates finishing in an exact tie is significantly higher than in any Canadian province. This has actually happened twice in the five elections to date, with exact ties in Akulliq in the Nunavut general election, 2008 and in Rankin Inlet South in the Nunavut general election, 2013. In such an event, Nunavut's practice is to schedule a follow-up by-election rather than choosing the winning candidate by an arbitrary method. The territory has also had numerous instances where MLAs were directly acclaimed to office as the only person to register their candidacy by the deadline, as well as one instance where a follow-up by-election had to be held due to no candidates registering for the regular election in their district at all.

Ceremony on the occasion of the foundation of Nunavut, April 1, 1999

Regions of Nunavut

Owing to Nunavut's vast size, the stated goal of the territorial government has been to decentralize governance beyond the region's capital. Three regions—Kitikmeot, Kivalliq and Qikiqtaaluk/Baffin—are the basis for more localized administration, although they lack autonomous governments of their own.[citation needed]

The territory has an annual budget of C$700 million, provided almost entirely by the federal government. Former Prime Minister Paul Martin designated support for Northern Canada as one of his priorities in 2004, with an extra $500 million to be divided among the three territories.[citation needed]

In 2001, the government of New Brunswick[citation needed] collaborated with the federal government and the technology firm SSI Micro to launch Qiniq, a unique network that uses satellite delivery to provide broadband Internet access to 24 communities in Nunavut. As a result, the territory was named one of the world's "Smart 25 Communities" in 2006 by the Intelligent Community Forum, a worldwide organization that honours innovation in broadband technologies. The Nunavut Public Library Services, the public library system serving the territory, also provides various information services to the territory.

In September 2012, Premier Aariak welcomed Prince Edward and Sophie, Countess of Wessex, to Nunavut as part of the events marking the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.[54]

Licence plates

The Nunavut licence plate was originally created for the Northwest Territories in the 1970s. The plate has long been famous worldwide for its unique design in the shape of a polar bear. Nunavut was licensed by the NWT to use the same licence plate design in 1999 when it became a separate territory,[55] but adopted its own plate design in March 2012 for launch in August 2012—a rectangle that prominently features the northern lights, a polar bear and an inuksuk.[55][56]

Flag and coat of arms

The flag and the coat of arms of Nunavut were designed by Andrew Karpik from Pangnirtung.[57]

Culture

Music

Inuit drum dancing, Gjoa Haven, Nunavut

The indigenous music of Nunavut includes Inuit throat singing and drum-led dancing, along with country music, bluegrass, square dancing, the button accordion and the fiddle, an infusion of European influence.

Media

The Inuit Broadcasting Corporation is based in Nunavut. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) serves Nunavut through a radio and television production centre in Iqaluit, and a bureau in Rankin Inlet. The territory is also served by two regional weekly newspapers Nunatsiaq News published by Nortext and Nunavut News/North, published by Northern News Services, who also publish the regional Kivalliq News.[58] Broadband internet is provided by Qiniq and Northwestel through Netkaster.[59][60]

Film

The film production company Isuma is based in Igloolik. Co-founded by Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn in 1990, the company produced the 1999 feature Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, winner of the Caméra d'Or for Best First Feature Film at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival. It was the first feature film written, directed, and acted entirely in Inuktitut.

In November 2006, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation announced the start of the Nunavut Animation Lab, offering animation training to Nunavut artists at workshops in Iqaluit, Cape Dorset and Pangnirtung.[61] Films from the Nunavut Animation Lab include Alethea Arnaquq-Baril's 2010 digital animation short Lumaajuuq, winner of the Best Aboriginal Award at the Golden Sheaf Awards and named Best Canadian Short Drama at the imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival.[62]

In November 2011, the government of Nunavut and the NFB jointly announced the launch of a DVD and online collection entitled Unikkausivut (Inuktitut: Sharing Our Stories), which will make over 100 NFB films by and about Inuit available in Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun and other Inuit languages, as well as English and French. The Government of Nunavut is distributing Unikkausivut to every school in the territory.[63][64]

Performing arts

Artcirq is a collective of Inuit circus performers based in Igloolik.[65] The group has performed around the world, including at the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Susan Aglukark is an Inuit singer and songwriter. She has released six albums and has won several Juno Awards. She blends the Inuktitut and English languages with contemporary pop music arrangements to tell the stories of her people, the Inuit of Arctic.

On May 3, 2008, the Kronos Quartet premiered a collaborative piece with Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq, entitled Nunavut, based on an Inuit folk story. Tagaq is also known internationally for her collaborations with Icelandic pop star Björk.

Jordin John Kudluk Tootoo (Inuktitut syllabics: ᔪᐊᑕᓐ ᑐᑐ; born February 2, 1983 in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada) is a professional ice hockey player with the Chicago Blackhawks of the National Hockey League (NHL). Although born in Manitoba, Tootoo grew up in Rankin Inlet, where he was taught to skate and play hockey by his father, Barney.

Alcohol

Due to prohibition laws influenced by local and traditional beliefs, Nunavut has a highly regulated alcohol market. It is the last outpost of prohibition in Canada, and it is often easier to obtain firearms than alcohol.[66] Every community in Nunavut has slightly differing regulations, but as a whole it is still very restrictive. Seven communities have bans against alcohol and another 14 have orders being restricted by local committees. Because of these laws, a lucrative bootlegging market has appeared where people mark up the prices of bottles by extraordinary amounts.[67] The RCMP estimate Nunavut's bootleg liquor market rakes in some $10 million a year.[66]

Despite the restrictions, alcohol's availability leads to widespread alcohol related crime. One lawyer estimated some 95% of police calls are alcohol-related.[68] Alcohol is also believed to be a contributing factor to the territory's high rates of violence, suicide, and homicide. A special task force created in 2010 to study and address the territory's increasing alcohol-related problems recommended the government ease alcohol restrictions. With prohibition shown to be highly ineffective historically, it is believed these laws contribute to the territory's widespread social ills. However, many residents are skeptical about the effectiveness of liquor sale liberalization and want to ban it completely. In 2014, Nunavut's government decided to move towards more legalization. A liquor store has opened in Iqaluit, the capital, for the first time in 38 years as of 2017.[66]

Sport

Nunavut has competed at the Arctic Winter Games and co-hosted the 2002 edition.

Hockey Nunavut was founded in 1999 and competes in the Maritime-Hockey North Junior C Championship.

See also

|

- Archaeology in Nunavut

- Arctic policy of Canada

Chemetco, U.S. company that produced air-borne dioxin inferred to be the source of contamination in Nunavut- Scouting and Guiding in Nunavut

- Symbols of Nunavut

- List of communities in Nunavut

Footnotes

^1 Effective November 12, 2008.

References

^ abcdef "Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2017-02-08..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Population by year of Canada of Canada and territories". Statistics Canada. September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

^ Nunavummiut, the plural demonym for residents of Nunavut, appears throughout the Government of Nunavut website Archived January 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., proceedings of the Nunavut legislature, and elsewhere. Nunavut Housing Corporation, Discussion Paper Released to Engage Nunavummiut on Development of Suicide Prevention Strategy. Alan Rayburn, previous head of the Canadian Permanent Committee of Geographical Names, opined that: "Nunavut is still too young to have acquired [a gentilé], although Nunavutan may be an obvious choice." In Naming Canada: stories about Canadian place names 2001. (2nd ed. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (

ISBN 0-8020-8293-9); p. 50.

^ ab "Consolidation of (S.Nu. 2008, c.10) (NIF) Official Languages Act" (PDF). and "Consolidation of Inuit Language Protection Act" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 20, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

^ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory (2011)". Statistics Canada. November 19, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

^ "The Official Flower of Nunavut: Purple Saxifrage". Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

^ "The Official Bird of Nunavut: The Rock Ptarmigan". Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

^ "Nunavut". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

^ ab "Nunavut Act". Justice Canada. 1993. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

^ ab Justice Canada (1993). "Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act". Retrieved August 7, 2018.

^ "How to Get Here". Nunavut Tourism. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

^ "Canadian Forces Station Alert - 8 Wing". Royal Canadian Air Force. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

^ "Cold Places in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

^ "Origin of the names of Canada and its provinces and territories". Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

^ "Nunavut".

^ See List of countries and outlying territories by total area

^ "CIA World Factbook". CIA. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

^ "Nunavut Alert - Whale Cove" (CSV (4222 KB)). Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2300MKF. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

[permanent dead link]

^ Jane George, "Kimmirut site suggests early European contact: Hare fur yarn, wooden tally sticks may mean visitors arrived 1,000 years ago" Archived August 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., Nunatsiaq News, September 12, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2009

^ "Nunavut: The Story of Canada's Inuit People" Archived October 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Maple Leaf Web

^ "Grise Fiord: History". Archived from the original on December 28, 2008.

^ McGrath, Melanie. The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (268 pages) Hardcover:

ISBN 0-00-715796-7 Paperback:

ISBN 0-00-715797-5

^ René Dussault and George Erasmus (1994). "The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation". Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Toronto: Canadian Government Publishing. fedpubs.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009.

^ Royte, Elizabeth (April 8, 2007). "Trail of Tears (review of Melanie McGrath, The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic (2006)". The New York Times.

^ Branch, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications. "Apology for the Inuit High Arctic relocation". www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

^ "Creation of a New Northwest Territories - Legislative Assembly of The Northwest Territories". www.assembly.gov.nt.ca.

^ Peter Jull (Summer 1988). "Building Nunavut: A Story of Inuit Self-Government". The Northern Review. Yukon College. pp. 59–72. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

^ "Creation of Nunavut". CBC News. 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

^ Statistics Canada (2006). "2006 Census Aboriginal Population Profiles". Retrieved January 16, 2008.

^ "Nunavut Tunngavik calls for equitable funding for Inuit languages". cbc.ca. CBC News.

^ What are the Official Languages of Nunavut? at the Office of the Language Commissioner of Nunavut

^ Board of Education (2000). "Summary of Aajiiqatigiingniq" (PDF). gov.nu.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2007. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

^ "Detailed Mother Tongue (186), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) (3) (2006 Census)". 2.statcan.ca. December 7, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

^ Population by knowledge of official language, by province and territory (2006 Census) Archived January 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

^ "Selected Religions, for Canada, Provinces and Territories – 20% Sample Data". 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

^ "Travel". Nunavut Mining Symposium. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

^ "Wolfden Resources". Wolfden Resources. August 31, 2007. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

^ The NorTerra Group of Companies Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., corporate website

^ Northern Transportation Company Limited at NorTerra Archived March 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., corporate website

^ "Nunasi Corp. sells its stake in NorTerra, Canadian North". April 1, 2014.

^ "NunatsiaqOnline 2014-04-01: NEWS: Nunasi Corp. sells its half of Norterra to the Inuvialuit".

^ "Nunavut FAQs - Government of Nunavut". www.gov.nu.ca.

^ "Canada's North struggles to ditch diesel". Alberta Oil Magazine – Canada's leading source for oil and gas news. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

^ ab Van Loon, Jeremy (December 7, 2011). "Nunavut Region to Boost Renewable Power to Offset Climate Change". Bloomberg.

^ McDonald, N.C.; J.M. Pearce (2012). "Renewable Energy Policies and Programs in Nunavut: Perspectives from the Federal and Territorial Governments". Arctic. 65 (4): 465–475. doi:10.14430/arctic4244.

^ Nicole C. McDonald & Joshua M. Pearce, "Community Voices: Perspectives on Renewable Energy in Nunavut" Archived July 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., Arctic 66(1), pp. 94–104 (2013).

^ Nunavut and Climate Change Archived April 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada

^ "Climate Change FAQ". Climate Change Nunavut. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013.

^ "Nellie Kusugak named as new Nunavut commissioner". CBC News. June 23, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

^ CBC Digital Archives (2006). "On the Nunavut Campaign Trail". CBC News. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

^ Weber, Bob (June 14, 2018). "After Paul Quassa ejected, Nunavut chooses deputy as new premier".

^ "Joe Savikataaq is the new premier of Nunavut, after non-confidence vote ousts former leader - CBC News".

^ "GN appoints IQ advisory council". Nunatsiaq Online. September 12, 2003. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

^ "Prince Edward and wife Sophie arrive in Iqaluit". CBC News. September 13, 2012.

^ ab Sarah Rogers (March 6, 2012). "GN launches new license plate". Nunatsiaq Online.

^ "Nunavut licence plates 1999–present". 15q.net. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

^ "Facts about Nunavut: About the Flag and Coat of Arms". Archived from the original on March 7, 2013.

^ "Newspapers in Nunavut". Altstuff.com. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

^ "Qiniq". Qiniq. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

^ "Netkaster". Netkaster.ca. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

^ George, Jane (November 3, 2006). "Nunavut's getting animated". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

^ "Nunavut Animation Lab: Lumaajuuq". Collection. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

^ "Inuit films move online and into northern communities". CBC News. November 2, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

^ "New NFB collection includes 24 films on or by Inuit". Nunatsiaq News. November 4, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

^ "Bringing circus – and new hope – to a remote Arctic village". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

^ abc "Iqaluit hopes to curb alcoholism and binge-drinking by opening city's first beer store in 38 years". National Post. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

^ VICE (January 14, 2015). "Prohibition in Northern Canada: VICE INTL (Canada)". Retrieved 2015-11-23 – via YouTube.

^ Communications, Government of Canada, Department of Justice, Electronic. "Department of Justice - Legal Aid, Courtworker, and Public Legal Education and Information Needs in the Northwest Territories". www.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Alia, Valerie. (2007) Names and Nunavut Culture and Identity in Arctic Canada. New York: Berghahn Books.

ISBN 1-84545-165-1 - Henderson, Ailsa. (2007) Nunavut: Rethinking Political Culture. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

ISBN 0-7748-1423-3

Dahl, Jens; Hicks, Jack; Jull, Peter, eds. (2002), Nunavut: Inuit regain control of their lands and their lives, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, ISBN 87-90730-34-8- Kulchyski, Peter Keith. (2005) Like the Sound of a Drum: Aboriginal Cultural Politics in Denendeh and Nunavut. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

ISBN 0-88755-178-5 - Sanna, Ellyn, and William Hunter. (2008) Canada's Modern-Day Aboriginal Peoples Nunavut & Evolving Relationships. Markham, Ont: Scholastic Canada.

ISBN 978-0-7791-7322-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nunavut. |

| Look up Nunavut in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Nunavut Kavamat / Government of Nunavut: Official site

Nunavut at Curlie

Map showing regions of Nunavut (from Nunavut Government website)- Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

- Nunavut Planning Commission

- Annual Nunavut Mining Symposium held in April each year

Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.: Nunavut Land Claims website- The Nunavut Act of 1993 at Canadian Legal Information Institute

Nunavut K-12 bilingual language instruction plan at the Wayback Machine (archived September 26, 2006): Martin, Ian. Aajiiqatigiingniq Language of Instruction Research Paper. Nunavut: Dept. of Education, 2000.[dead link]

Tourism

- Explore Nunavut: Travel information and community guides

- Nunavut Parks

- Nunavut Tourism

Journalism

CBC North Radio: hear Inuktitut and English radio from Nunavut

Territorial newspaper reporting in Inuktitut and English, Nunatsiaq News

Nunavut News from News/North

Coordinates: 73°N 091°W / 73°N 91°W / 73; -91