Ancona

Ancona | ||

|---|---|---|

Comune | ||

| Città di Ancona | ||

Aerial view of Ancona | ||

| ||

Location of Ancona | ||

Ancona Location of Ancona in Marche Show map of Italy  Ancona Ancona (Marche) Show map of Marche | ||

| Coordinates: 43°37′01″N 13°31′00″E / 43.61694°N 13.51667°E / 43.61694; 13.51667Coordinates: 43°37′01″N 13°31′00″E / 43.61694°N 13.51667°E / 43.61694; 13.51667 | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Marche | |

| Province | Ancona (AN) | |

| Frazioni | Aspio, Gallignano, Montacuto, Massignano, Montesicuro, Candia, Ghettarello, Paterno, Casine di Paterno, Poggio di Ancona, Sappanico, Varano | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Valeria Mancinelli (PD) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 123.71 km2 (47.76 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 16 m (52 ft) | |

| Population (30 April 2015) | ||

| • Total | 101,300 | |

| • Density | 820/km2 (2,100/sq mi) | |

| Demonyms | Anconetani, Anconitani | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Postal code | 60100, from 60121 to 60129, 60131 | |

| Dialing code | 071 | |

| Patron saint | Judas Cyriacus | |

| Saint day | 4 May | |

| Website | Official website | |

Ancona (Italian pronunciation: [aŋˈkoːna] (![]() listen); Greek: Ἀγκών – Ankon (elbow); Friulian: Ancone) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 as of 2015[update]. Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located 280 km (170 mi) northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic Sea, between the slopes of the two extremities of the promontory of Monte Conero, Monte Astagno and Monte Guasco.

listen); Greek: Ἀγκών – Ankon (elbow); Friulian: Ancone) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 as of 2015[update]. Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located 280 km (170 mi) northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic Sea, between the slopes of the two extremities of the promontory of Monte Conero, Monte Astagno and Monte Guasco.

Ancona is one of the main ports on the Adriatic Sea, especially for passenger traffic, and is the main economic and demographic centre of the region.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Greek colony

1.2 Roman Municipum

1.3 Byzantine city

1.4 Maritime Republic of Ancona

1.5 In the Papal States

1.5.1 The Greek community of Ancona in the 16th century

1.6 Contemporary history

1.7 Jewish history

2 Geography

2.1 Climate

3 Demographics

4 Government

5 Main sights

5.1 Ancona Cathedral

5.2 Other sights

6 Transportation

6.1 Shipping

6.2 Airport

6.3 Railways

6.4 Roads

6.5 Urban public transportation

7 International relations

7.1 Twin towns – Sister cities

8 Gallery

9 See also

10 References

11 Sources

12 External links

History

Borders and castles of the Republic of Ancona in the 15th century.

The Vanvitelli's Lazzaretto.

The portal of the church of San Francesco.

Greek colony

Ancona was founded by Greek settlers from Syracuse in about 387 BC, who gave it its name: Ancona stems from the Greek word Ἀγκών (Ankòn), meaning "elbow"; the harbour to the east of the town was originally protected only by the promontory on the north, shaped like an elbow. Greek merchants established a Tyrian purple dye factory here.[1] In Roman times it kept its own coinage with the punning device of the bent arm holding a palm branch, and the head of Aphrodite on the reverse, and continued the use of the Greek language.[2]

Roman Municipum

When it became a Roman town is uncertain. It was occupied as a naval station in the Illyrian War of 178 BC.[3]Julius Caesar took possession of it immediately after crossing the Rubicon. Its harbour was of considerable importance in imperial times, as the nearest to Dalmatia, and was enlarged by Trajan, who constructed the north quay with his Syrian architect Apollodorus of Damascus. At the beginning of it stands the marble triumphal arch with a single archway, and without bas-reliefs, erected in his honour in 115 by the Senate and Roman people.[2]

Byzantine city

Ancona was successively attacked by the Goths, Lombards and Saracens between the 3rd and 5th centuries, but recovered its strength and importance. It was one of the cities of the Pentapolis of the Exarchate of Ravenna, a lordship of the Byzantine Empire, in the 7th and 8th centuries.[2][4] In 840, Saracen raiders sacked and burned the city.[5] After Charlemagne's conquest of northern Italy, it became the capital of the Marca di Ancona, whence the name of the modern region.

Maritime Republic of Ancona

After 1000, Ancona became increasingly independent, eventually turning into an important maritime republic (together with Gaeta and Ragusa, it is one of those not appearing on the Italian naval flag), often clashing against the nearby power of Venice. An oligarchic republic, Ancona was ruled by six Elders, elected by the three terzieri into which the city was divided: S. Pietro, Porto and Capodimonte. It had a coin of its own, the agontano, and a series of laws known as Statuti del mare e del Terzenale and Statuti della Dogana. Ancona was usually allied with the Republic of Ragusa and the Byzantine Empire.

In 1137, 1167 and 1174 it was strong enough to push back the forces of the Holy Roman Empire. Anconitan ships took part in the Crusades, and their navigators included Cyriac of Ancona. In the struggle between the Popes and the Holy Roman Emperors that troubled Italy from the 12th century onwards, Ancona sided with the Guelphs.

Trade routes and warehouses of the maritime republic of Ancona

Differently from other cities of northern Italy, Ancona never became a seignory. The sole exception was the rule of the Malatesta, who took the city in 1348 taking advantage of the black death and of a fire that had destroyed many of its important buildings. The Malatesta were ousted in 1383. In 1532 it definitively lost its freedom and became part of the Papal States, under Pope Clement VII. Symbol of the papal authority was the massive Citadel.

In the Papal States

Together with Rome, and Avignon in southern France, Ancona was the sole city in the Papal States in which the Jews were allowed to stay after 1569, living in the ghetto built after 1555.

In 1733 Pope Clement XII extended the quay, and an inferior imitation of Trajan's arch was set up; he also erected a Lazaretto at the south end of the harbour, Luigi Vanvitelli being the architect-in-chief. The southern quay was built in 1880, and the harbour was protected by forts on the heights. From 1797 onwards, when the French took it, it frequently appears in history as an important fortress.

The Greek community of Ancona in the 16th century

Ancona, as well as Venice, became a very important destination for merchants from the Ottoman Empire during the 16th century. The Greeks formed the largest of the communities of foreign merchants. They were refugees from former Byzantine or Venetian territories that were occupied by the Ottomans in the late 15th and 16th centuries. The first Greek community was established in Ancona early in the 16th century. Natalucci, the 17th-century historian of the city, notes the existence of 200 Greek families in Ancona at the opening of the 16th century. Most of them came from northwestern Greece, i.e. the Ionian islands and Epirus. In 1514, Dimitri Caloiri of Ioannina obtained reduced custom duties for Greek merchants coming from the towns of Ioannina, Arta and Avlona in Epirus. In 1518 a Jewish merchant of Avlona succeeded in lowering the duties paid in Ancona for all “the Levantine merchants, subjects to the Turk”.

In 1531 the Confraternity of the Greeks (Confraternita dei Greci) was established which included Orthodox Catholic and Roman Catholic Greeks. They secured the use of the Church of St. Anna dei Greci and were granted permission to hold services according to the Greek and the Latin rite. The church of St. Anna had existed since the 13th century, initially as "Santa Maria in Porta Cipriana," on ruins of the ancient Greek walls of Ancona.

In 1534 a decision by Pope Paul III favoured the activity of merchants of all nationalities and religions from the Levant and allowed them to settle in Ancona with their families. A Venetian travelling through Ancona in 1535 recorded that the city was "full of merchants from every nation and mostly Greeks and Turks." In the second half of the 16th century, the presence of Greek and other merchants from the Ottoman Empire declined after a series of restrictive measures taken by the Italian authorities and the pope.

Disputes between the Orthodox Catholic and Roman Catholic Greeks of the community were frequent and persisted until 1797 when the city was occupied by France who closed all the religious confraternities and confiscated the archive of the Greek community. The French would return to the area to reoccupy it in 1805-1806. The church of St. Anna dei Greci was re-opened to services in 1822. In 1835, in the absence of a Greek community in Ancona, it passed to the Latin Church.[6][7]

Contemporary history

Ancona entered the Kingdom of Italy when Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière surrendered here on 29 September 1860, eleven days after his defeat at Castelfidardo.[2]

On 23 May 1915, Italy entered World War I and joined the Entente Powers. In 1915, following Italy's entry, the battleship division of the Austro-Hungarian Navy carried out extensive bombardments causing great damage to all installations and killing several dozen people.[8] Ancona was one of the most important Italian ports on the Adriatic Sea during the Great War.

During World War II, the city was taken by the Polish 2nd Corps against Nazi German forces, as Free Polish forces were serving as part of the British Army.

Poles were tasked with capture of the city on 16 June 1944 and accomplished the task a month later on 18 July 1944 in what is known as the battle of Ancona.

The attack was part of an Allied operation to gain access to a seaport closer to the Gothic Line in order to shorten their lines of communication for the advance into northern Italy.[9]

Jewish history

Jews began to live in Ancona in 967 A.D.[10] In 1270, a Jewish resident of Ancona, Jacob of Ancona, travelled to China, four years before Marco Polo and documented his impressions in a book called "The City of Lights". From 1300 and on, the Jewish community of Ancona grew steadily, most due to the city importance and it being a center of trade with the Levant. In that year, Jewish poet Immanuel the Roman tried to lower high taxation taken from the Jewish community of the city. Over the next 200 years, Jews from Germany, Spain, Sicily and Portugal immigrated to Ancona, due to persecutions in their homeland and thanks to the pro-Jewish attitude taken towards Ancona Jews due to their importance in the trade and banking business, making Ancona a trade center. In 1550, the Jewish population of Ancona numbered about 2700 individuals.[11]

In 1555, pope Paul IV forced the Crypto-Jewish community of the city to convert to Christianity, as part of his Papal Bull of 1555. While some did, others refused to do so and thus were hanged and then burnt in the town square.[11] In response, Jewish merchants boycotted Ancona for a short while. The boycott was led by Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi.

Though emancipated by Napoleon I for several years, in 1843 Pope Gregory XVI revived an old decree, forbidding Jews from living outside the ghetto, wearing identification sign on their clothes and other religious and financial restrictions, though public opinion did not approve of these restrictions and they were cancelled a short while after.[12]

The Jews of Ancona received full emancipation in 1848 with the election of Pope Pius IX. In 1938, 1177 lived in Ancona.[12] 53 Jews were sent away to Germany, 15 of them survived and returned to the town after World War II. The majority of the Jewish community stayed in town or immigrated due to high ransoms paid to the fascist regime. In 2004, about 200 Jews lived in Ancona.

Two synagogues and two cemeteries still exist in the city. The ancient Monte-Cardeto cemetery is one of the biggest Jewish cemeteries in Europe and tombstones are dated to 1552 and on. It can still be visited and it resides within the Parco del Cardeto.

Geography

Climate

The climate of Ancona is humid subtropical (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification) and the city lies on the border between mediterranean and more continental regions. Precipitations are regular throughout the year. Winters are cool (January mean temp. 5 °C or 41 °F), with frequent rain and fog. Temperatures can reach −10 °C (14 °F) or even lower values outside the city centre during the most intense cold waves. Snow is not unusual with air masses coming from Northern Europe or from the Balkans and Russia, and can be heavy at times (also due to the "Adriatic sea effect"), especially in the hills surrounding the city centre. Summers are usually warm and humid (July mean temp. 22.5 °C or 72.5 °F). Highs sometimes reach values around 35 and 40 °C (95 and 104 °F), especially if the wind is blowing from the south or from the west (föhn effect off the Appennine mountains). Thunderstorms are quite common, particularly in August and September, when can be intense with occasional flash floods. Spring and autumn are both seasons with changeable weather, but generally mild. Extremes in temperature have been −15.4 °C (4.3 °F) (in 1967) and 40.8 °C (105.4 °F) (in 1968) / 40.5 °C (104.9 °F) (in 1983).

| Climate data for Ancona (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) | 10.2 (50.4) | 13.6 (56.5) | 16.9 (62.4) | 21.7 (71.1) | 25.6 (78.1) | 28.2 (82.8) | 28.1 (82.6) | 24.5 (76.1) | 19.4 (66.9) | 13.9 (57) | 10.4 (50.7) | 18.5 (65.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) | 5.9 (42.6) | 8.6 (47.5) | 11.6 (52.9) | 16.3 (61.3) | 20.1 (68.2) | 22.6 (72.7) | 22.7 (72.9) | 19.3 (66.7) | 14.7 (58.5) | 9.8 (49.6) | 6.5 (43.7) | 13.6 (56.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) | 1.6 (34.9) | 3.6 (38.5) | 6.4 (43.5) | 10.9 (51.6) | 14.5 (58.1) | 16.9 (62.4) | 17.2 (63) | 14.0 (57.2) | 10.0 (50) | 5.7 (42.3) | 2.6 (36.7) | 8.7 (47.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.8 (1.72) | 49.3 (1.94) | 56.8 (2.24) | 58.8 (2.31) | 54.0 (2.13) | 60.4 (2.38) | 47.1 (1.85) | 76.4 (3.01) | 72.6 (2.86) | 75.9 (2.99) | 86.0 (3.39) | 58.1 (2.29) | 739.2 (29.1) |

| Source: MeteoAM [13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1174 | 11,000 | — |

| 1565 | 18,435 | +67.6% |

| 1582 | 27,770 | +50.6% |

| 1656 | 17,033 | −38.7% |

| 1701 | 16,212 | −4.8% |

| 1708 | 16,194 | −0.1% |

| 1769 | 23,028 | +42.2% |

| 1809 | 31,231 | +35.6% |

| 1816 | 32,636 | +4.5% |

| 1828 | 36,816 | +12.8% |

| 1844 | 43,217 | +17.4% |

| 1846 | 43,953 | +1.7% |

| 1853 | 44,833 | +2.0% |

| 1861 | 47,230 | +5.3% |

| 1871 | 45,681 | −3.3% |

| 1881 | 48,888 | +7.0% |

| 1901 | 58,602 | +19.9% |

| 1911 | 65,388 | +11.6% |

| 1921 | 68,521 | +4.8% |

| 1931 | 75,372 | +10.0% |

| 1936 | 78,639 | +4.3% |

| 1951 | 85,763 | +9.1% |

| 1961 | 100,485 | +17.2% |

| 1971 | 109,789 | +9.3% |

| 1981 | 106,432 | −3.1% |

| 1991 | 101,285 | −4.8% |

| 2001 | 100,507 | −0.8% |

| 2010 | 102,997 | +2.5% |

| Source: P. Burattini. Stradario – Guida della città di Ancona (Ancona, 1951) and ISTAT | ||

In 2007, there were 101,480 people residing in Ancona (the greater area has a population more than four times its size), located in the province of Ancona, Marches, of whom 47.6% were male and 52.4% were female. Minors (children ages 18 and younger) totalled 15.54 percent of the population compared to pensioners who number 24.06 percent. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06 percent (minors) and 19.94 percent (pensioners). The average age of Ancona resident is 48 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Ancona grew by 1.48 percent, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.56 percent.[14][15] The current birth rate of Ancona is 8.14 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.

As of 2006[update], 92.77% of the population was Italian. The largest immigrant group came from other European nations (particularly those from Albania, Romania and Ukraine): 3.14%, followed by the Americas: 0.93%, East Asia: 0.83%, and North Africa: 0.80%.

Government

Main sights

Ancona Cathedral

Ancona Cathedral, dedicated to Judas Cyriacus, was consecrated at the beginning of the 11th century and completed in 1189.[16] Some writers suppose that the original church was in the form of a basilica and belonged to the 7th century. An early restoration was completed in 1234. It is a fine Romanesque building in grey stone, built in the form of a Greek cross, and other elements of Byzantine art. It has a dodecagonal dome over the centre slightly altered by Margaritone d'Arezzo in 1270. The façade has a Gothic portal, ascribed to Giorgio da Como (1228), which was intended to have a lateral arch on each side.

A cannon situated near the Arch of Trajan, with the Cattedrale San Ciriaco visible in the background.

Gothic/Renaissance portal of the church of Sant'Agostino.

The interior, which has a crypt under each transept, in the main preserves its original character. It has ten columns which are attributed to the temple of Venus.[2] The church was restored in the 1980s.

Other sights

Arch of Trajan: this is a marble 18 metres (59 feet) high, erected in 114/115 as an entrance to the causeway atop the harbour wall in honour of the emperor who had made the harbour, is one of the finest Roman monuments in the Marches. Most of its original bronze enrichments have disappeared. It stands on a high podium approached by a wide flight of steps. The archway, only 3 metres (9.8 feet) wide, is flanked by pairs of fluted Corinthian columns on pedestals. An attic bears inscriptions. The format is that of the Arch of Titus in Rome, but made taller, so that the bronze figures surmounting it, of Trajan, his wife Plotina and sister Marciana, would figure as a landmark for ships approaching Rome's greatest Adriatic port.

Lazzaretto: The complex is a (Laemocomium or "Mole Vanvitelliana"), planned by architect Luigi Vanvitelli in 1732 is a pentagonal building covering more than 20,000 square metres (220,000 square feet), built to protect the military defensive authorities from the risk of contagious diseases eventually reaching the town with the ships. Later it was used also as a military hospital or as barracks; it is currently used for cultural exhibits.- The Episcopal Palace was the place where Pope Pius II died in 1464.

Santa Maria della Piazza: church with an elaborate arcaded façade (1210).[2]

Palazzo del Comune (or Palazzo degli Anziani – Elders palace): The palace was built in 1250, with lofty arched substructures at the back, was the work of Margaritone d'Arezzo, and has been restored twice.[2]

San Francesco alle Scale: Franciscan church

Sant'Agostino: Augustinian church in 1341 as Santa Maria del Popolo, and enlarged by Luigi Vanvitelli in the 18th century and turned into a palace after 1860. It has a portal by Giorgio da Sebenico combining Gothic and Renaissance elements, with statues portraying St. Monica, St. Nicola da Tolentino, St. Simplicianus and Blessed Agostino Trionfi.

Santi Pellegrino e Teresa: 18th century church

Santissimo Sacramento: 16th and 18th century church

There are also several fine late Gothic buildings, including the Palazzo Benincasa, the Palazzo del Senato and the Loggia dei Mercanti, all by Giorgio da Sebenico, and the prefecture, which has Renaissance additions.[2]

The National Archaeological Museum (Museo Archeologico Nazionale) is housed in the Palazzo Ferretti, built in the late Renaissance by Pellegrino Tibaldi; it preserves frescoes by Federico Zuccari. The Museum is divided into several sections:

- prehistoric section, with palaeolithic and neolithic artefacts, objects of the Copper Age and of the Bronze Age

- protohistoric section, with the richest existing collection of the Picenian civilization; the section includes a remarkable collection of Greek ceramics

- Greek-Hellenistic section, with coins, inscriptions, glassware and other objects from the necropolis of Ancona

- Roman section, with a statue of Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, carved sarcophagi and two Roman beds with fine decorations in ivory[2]

- rich collection of ancient coins (not yet exposed)

The port of Ancona

The Municipal Art Gallery (Pinacoteca Civica Francesco Podesti) is housed in the Palazzo Bosdari, reconstructed between 1558 and 1561 by Pellegrino Tibaldi. Works in the gallery include:

Circumcision, Dormitio Virginis and Crowned Virgin, by Olivuccio di Ciccarello

Madonna with Child, panel by Carlo Crivelli

Gozzi Altarpiece by Titian

Sacra Conversazione by Lorenzo Lotto

Portrait of Francesco Arsilli by Sebastiano Del Piombo

Circumcision by Orazio Gentileschi

Immaculate Conception and St. Palazia by Guercino

Four Saints in Ecstasis, Panorama of Ancona in the sixteenth century and Musician Angels by Andrea Lillio

Other artists present include Ciro Ferri and Arcangelo di Cola (flourished 1416–1429). Modern artists featured are Bartolini, Bucci, Campigli, Bruno Cassinari, Cucchi, Levi, Sassu, Orfeo Tamburi, Trubbiani, Francesco Podesti and others.

Angelo Messi, ancestor of famous football star Lionel Messi, emigrated from Ancona to Rosario, Argentina in the 1880s.

Ancona is also the city of the birth of Italian opera singer, Franco Corelli.

Transportation

Shipping

The Port has regular ferry links to the following cities with the following operators:

Adria Ferries (Durrës)

Blue Line International (Split, Stari Grad, Vis)

Jadrolinija (Split, Zadar)

SNAV (Split) (seasonal)

Superfast Ferries (Igoumenitsa, Patras)

ANEK Lines (Igoumenitsa, Patras)

Minoan Lines (Igoumenitsa, Patras)

Marmara Lines (Cesme)

Airport

Ancona is served by Ancona Airport (IATA: AOI, ICAO: LIPY), in Falconara Marittima and named after Raffaello Sanzio.

European Coastal Airlines, a seaplane operator, established trans-Adriatic flights between Croatia and Italy in November 2015 and offers four weekly flights from Ancona Falconara Airport and Split (59 minutes) and Rijeka Airport (49 minutes).

Railways

The Ancona railway station is the main railway station of the city and is served by regional and long-distance trains. The other stations are Ancona Marittima, Ancona Torrette, Ancona Stadio, Palombina and Varano.

Roads

The A14 motorway serves the city with the exits "Ancona Nord" (An. North) and "Ancona Sud" (An. South).

Urban public transportation

The Ancona trolleybus system has been in operation since 1949. Ancona is also served by an urban bus network.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Ancona is twinned with:

İzmir, Turkey

İzmir, Turkey Galaţi, Romania

Galaţi, Romania Split, Croatia[17]

Split, Croatia[17] Ribnica, Slovenia

Ribnica, Slovenia Svolvær, Norway

Svolvær, Norway Castlebar, Ireland

Castlebar, Ireland Granby, Canada

Granby, Canada

Gallery

See also

- Maritime republics

- Biblioteca comunale Luciano Benincasa

- U.S. Ancona 1905

- History of A.C. Ancona

- Stadio del Conero

- University of Ancona

References

^ Silius Italicus, VIII. 438

^ abcdefghi One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ancona". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 951–952..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ancona". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 951–952..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Livy xli. i

^ The other four were Fano, Pesaro, Senigallia and Rimini

^ The Italian Cities and the Arabs before 1095, Hilmar C. Krueger, A History of the Crusades: The First Hundred Years, Vol.I, ed. Kenneth Meyer Setton, Marshall W. Baldwin, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1955), 47.

^ Greene Molly (2010) Catholic pirates and Greek merchants: a maritime history of the Mediterranean. Princeton University Press, Britain, pp. 15–51.

^ Rentetzi Efthalia (2007) La chiesa di Sant' Anna dei Greci di Ancona. Thesaurismata (Instituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini di Venezia), vol. 37.

^ Hore, Peter, The Ironclads, London, Southwater Publishing, 2006.

ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

^ Jerzy Bordziłowski (ed. ), Mała encyklopedia wojskowa. Tom 1 (in Polish), Warsaw, Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1967.

^ "The Jewish Community of Ancona". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

^ ab Ancona Jews#cite note-1

^ ab https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0002_0_01073.html

^ "Falconara" (PDF). Italian Air Force National Meteorological Service. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

^ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

^ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

^ San Ciriaco – La cattedrale di Ancona, Federico Motta editore, 2003

^ "Gradovi prijatelji Splita" [Split Twin Towns]. Grad Split [Split Official City Website] (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

Sources

"Ancona", Italy (2nd ed.), Coblenz: Karl Baedeker, 1870

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ancona. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancona. |

- Official website

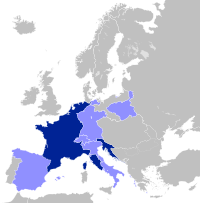

Europe at the height of Napoleon's Empire

Europe at the height of Napoleon's Empire