Chichimeca

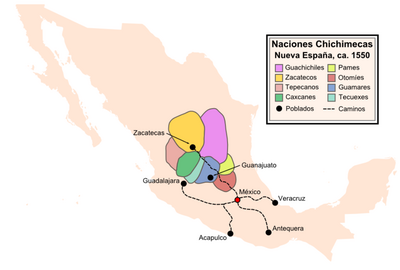

Map of the location of prominent Chichimeca peoples around 1550. Map only reflects core areas, as these tribes moved freely back and forth from what is now southern Utah and had definite settlements in what is now Texas.

Chichimeca (Spanish ![]() [tʃitʃiˈmeka] (help·info)) was the name that the Nahua peoples of Mexico generically applied to nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who were established in present-day Bajio region of Mexico. Chichimeca carried the same sense as the Roman term "barbarian" to describe Germanic tribes. The name, with its pejorative sense, was adopted by the Spanish Empire. For the Spanish, in the words of scholar Charlotte M. Gradie, "the Chichimecas were a wild, nomadic people who lived north of the Valley of Mexico. They had no fixed dwelling places, lived by hunting, wore little clothes and fiercely resisted foreign intrusion into their territory, which happened to contain silver mines the Spanish wished to exploit."[1]

[tʃitʃiˈmeka] (help·info)) was the name that the Nahua peoples of Mexico generically applied to nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who were established in present-day Bajio region of Mexico. Chichimeca carried the same sense as the Roman term "barbarian" to describe Germanic tribes. The name, with its pejorative sense, was adopted by the Spanish Empire. For the Spanish, in the words of scholar Charlotte M. Gradie, "the Chichimecas were a wild, nomadic people who lived north of the Valley of Mexico. They had no fixed dwelling places, lived by hunting, wore little clothes and fiercely resisted foreign intrusion into their territory, which happened to contain silver mines the Spanish wished to exploit."[1]

In modern times, only one ethnic group is customarily referred to as Chichimecs, namely the Chichimeca Jonaz, a few thousand of whom live in the state of Guanajuato.

Contents

1 Overview and identity

2 Etymology

3 Ethnohistorical descriptions

4 Wars with the Spanish

5 References

6 Sources

Overview and identity

The Chichimeca people consisted of eight nations that spoke different languages. As the Spaniards worked towards consolidating the rule of New Spain over the indigenous peoples during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Chichimecan nations resisted fiercely, although a number of native groups of the region allied with the Spanish. The most long-lasting of these conflicts (1550–91) was the Chichimeca War, resulting in the defeat of the Spanish Empire and a decisive victory for the Chichimeca Confederation.

Many of the peoples known broadly as Chichimeca are virtually unknown today; few descriptions recorded their names and they seem to have been absorbed into mestizo culture or into other indigenous ethnic groups. For example, virtually nothing is known about the peoples referred to as the Guachichil, Caxcan, Zacateco, Tecuexe, or Guamare. Others, such as the Opata or Eudeve, are well described in records but extinct as a people.[full citation needed]

Still other Chichimec peoples maintain separate identities into the present day, such as the Otomi, Chichimeca Jonaz, Cora, Huichol, Pame, Yaqui, Mayo, O'odham and the Tepehuan peoples.[full citation needed]

Etymology

The Nahuatl name Chīchīmēcah (plural, pronounced [tʃiːtʃiːˈmeːkaʔ]; singular Chīchīmēcatl) means "inhabitants of Chichiman," Chichiman meaning "area of milk." It is sometimes said to be related to chichi "dog", but the is in chichi are both short while those in Chīchīmēcah are long, which changes the meaning as vowel length is phonemic in Nahuatl.[2]

The Nahua originally used the word "Chichimeca" to refer to their own ancient history as a nomadic hunter-gatherer group, in contrast to their later, more urban culture, which they identified as Toltecatl.[3] In modern Mexico, the word "Chichimeca" can have pejorative connotations such as "primitive," "savage," "uneducated," and "native."[full citation needed]

Ethnohistorical descriptions

The first descriptions of "Chichimecs" are from the early colonization period. In 1526, Hernán Cortés wrote a letter about the northern Chichimec tribes, who were not as "civilized" to him as the Aztecs. He commented that they might be enslaved and used to work in the mines.[full citation needed]

The Chicimec, Caxcanes and other indigenous people of Northern Mexico fought against Spanish military forces, such as Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, when they began trying to enslave them. Their fight against Spanish military forces became known as the Mixtón Rebellion.[full citation needed]

In the late sixteenth century, Gonzalo de las Casas wrote about the Chichimec. He had received an encomienda near Durango and fought in the wars against the Chichimec peoples: the Pame, the Guachichile, the Guamari and the Zacateco, who lived in the area known at the time as "La Gran Chichimeca." Las Casas' account was called Report of the Chichimeca and the Justness of the War Against Them. He described the people, providing ethnographic information. He wrote that they only covered their genitalia with clothing; painted their bodies; and ate only game, roots and berries. He mentioned, in order to prove their supposed barbarity, that Chichimec women, having given birth, continued traveling on the same day without stopping to recover.[4] While las Casas recognized that the Chichimecan tribes spoke different languages, he considered their culture to be primarily uniform.[full citation needed]

In the late 16th century the Chichimeca did not worship deities as did many of the surrounding indigenous peoples[5] and in the eyes of the Franciscan priest Alonso Ponce this was an indication that the Chicimeca had a barbarous nature. Bernardino de Sahagún's Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España provides a fuller account: he describes some Chichimec people, such as the Otomi, as knowing agriculture, living in settled communities, and having a religion devoted to the worship of the moon.[full citation needed]

Early sources was typical of the era in their efforts to spread propaganda that the natives were "savages" - accomplished at war and hunting, but with no established society or morals, and prone to fighting among themselves. This stereotype became even more prevalent during the course of the Chichimec wars, acting as a justification for the wars.[full citation needed]

The first description of a modern objective ethnography of the peoples inhabiting La Gran Chichimeca was done by Norwegian naturalist and explorer Carl Sofus Lumholtz in 1890 when he traveled on muleback through northwestern Mexico, meeting the indigenous peoples on friendly terms. With his descriptions of the rich and different cultures of the various "uncivilized" tribes, the picture of the uniform Chichimec barbarians was changed – although in Mexican Spanish the word "Chichimeca" remains connected to an image of "savagery".[full citation needed]

The historian Paul Kirchhoff, in his work The Hunting-Gathering People of North Mexico, described the Chichimecas as sharing a hunter-gatherer culture, based on the gathering of mesquite, agave, and tunas (the fruit of the nopal), with others also using acorns, roots and seeds. In some areas, the Chichimeca cultivated maize and calabash. From the mesquite, the Chichamecs made white bread and wine. Many Chichimec tribes used the juice of the agave as a substitute for water when it was in short supply.[full citation needed]

Wars with the Spanish

Chichimeca military strikes against the Spanish included raidings, ambushing critical economic routes, and pillaging. In the long-running Chichimeca War (1550–1590), the Spanish initially attempted to defeat the combined Chichimeca peoples in a war of "fire and blood", but eventually sought peace as they were unable to defeat them. The Chichimeca's small-scale raids proved effective. To end the war, the Spanish adopted a "Purchase for Peace" program by providing foods, tools, livestock, and land to the Chichimecas, sending Spanish to teach them agriculture as a livelihood, and by passively converting them to Catholicism. Within a century, the Spanish and Chichimeca were assimilated.[6]

References

^ Gradie, Charlotte M. "Discovering the Chichimecas" Academy of American Franciscan History, Vol 51, No. 1 (July 1994), p. 68

^ See Andrews 2003 (pp.496 and 507), Karttunen 1983 (p.48), and Lockhart 2001 (p.214)

^ This term caused confusion in later scholarship, as it was understood to refer to a specific ethnic group.

^ As cited in Gradie (1994).

^ http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/Chichimecas.pdf

^ Powell, Phillip Wayne (1952), Soldiers, Indians & Silver, Berkeley: U of California Press, pp. 182-199; LatinoLA | Comunidad :: Indigenous Origins

Sources

Andrews, J. Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (Revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Gradie, Charlotte M. (1994). "Discovering the Chichimeca". Americas. The Americas, Vol. 51, No. 1. 51 (1): 67–88. doi:10.2307/1008356. JSTOR 1008356.

Karttunen, Frances (1983). An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Lockhart, James (2001). Nahuatl as Written. Stanford University Press.

Lumholtz, Carl (1987) [1900]. Unknown Mexico, Explorations in the Sierra Madre and Other Regions, 1890-1898. 2 vols (reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

Powell, Philip Wayne (1969). Soldiers, Indians, & Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550-1600. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Secretariá de Turismo del Estado de Zacatecas (2005). "Zonas Arqueológicas" (in Spanish).

Smith, Michael E. (1984). "The Aztlan Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?" (PDF online facsimile). Ethnohistory. Columbus, OH: American Society for Ethnohistory. 31 (3): 153–186. doi:10.2307/482619. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482619. OCLC 145142543.